In recent years, the issue of fertility rates has become an increasingly vital issue, as more and more nations across the globe begin to confront fertility rates significantly below replacement levels.

Ironically, the Howard government saw the demographic issues that could arise in time if Australia’s fertility rate were to remain significantly below replacement levels.

In 2004, then Treasurer Peter Costello unveiled the slogan:

“You should have one (child) for the father, one for the mother, and one for the country.”

This era saw the implementation of the Howard government’s ‘Baby Bonus’ program, a cash payment to mothers for each child they had.

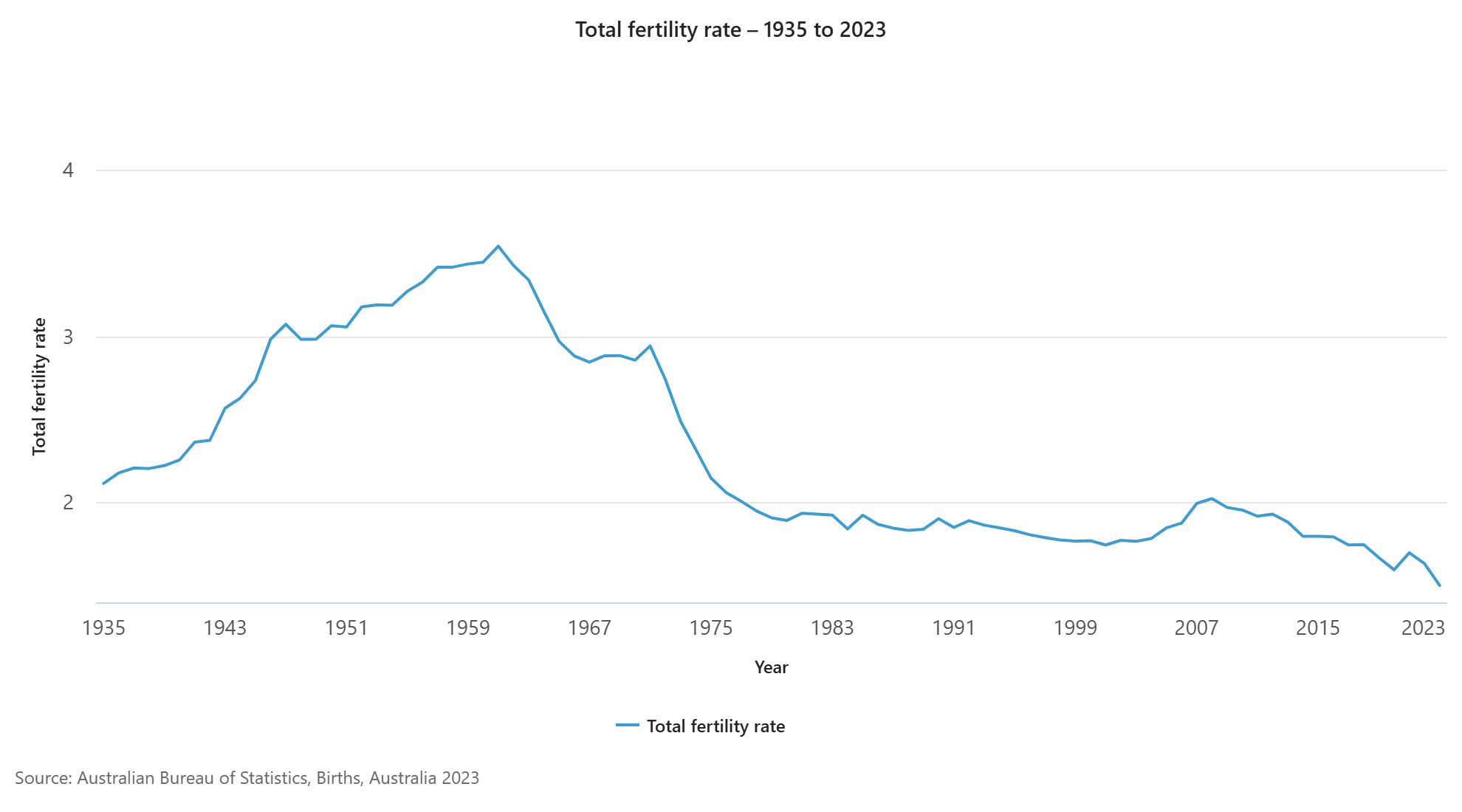

In 2002, the year the Baby Bonus was introduced, Australia’s fertility rate was 1.76 children per woman.

By the time of the post-1970s peak in fertility rates in 2008, the figure had risen to 1.95 children per woman.

To what degree the ‘Baby Bonus’ played a role remains a source of debate among economists and academics to this day.

But while the Howard government was attempting to forge a more favourable demographic path through policies such as the Baby Bonus and government campaigns encouraging larger families, it was simultaneously pursuing a set of policy settings that would have the opposite effect.

Amidst the meteoric rise in property investor demand, the introduction of a cash first home buyer grant and the introduction of the capital gains tax discount, housing affordability swiftly deteriorated.

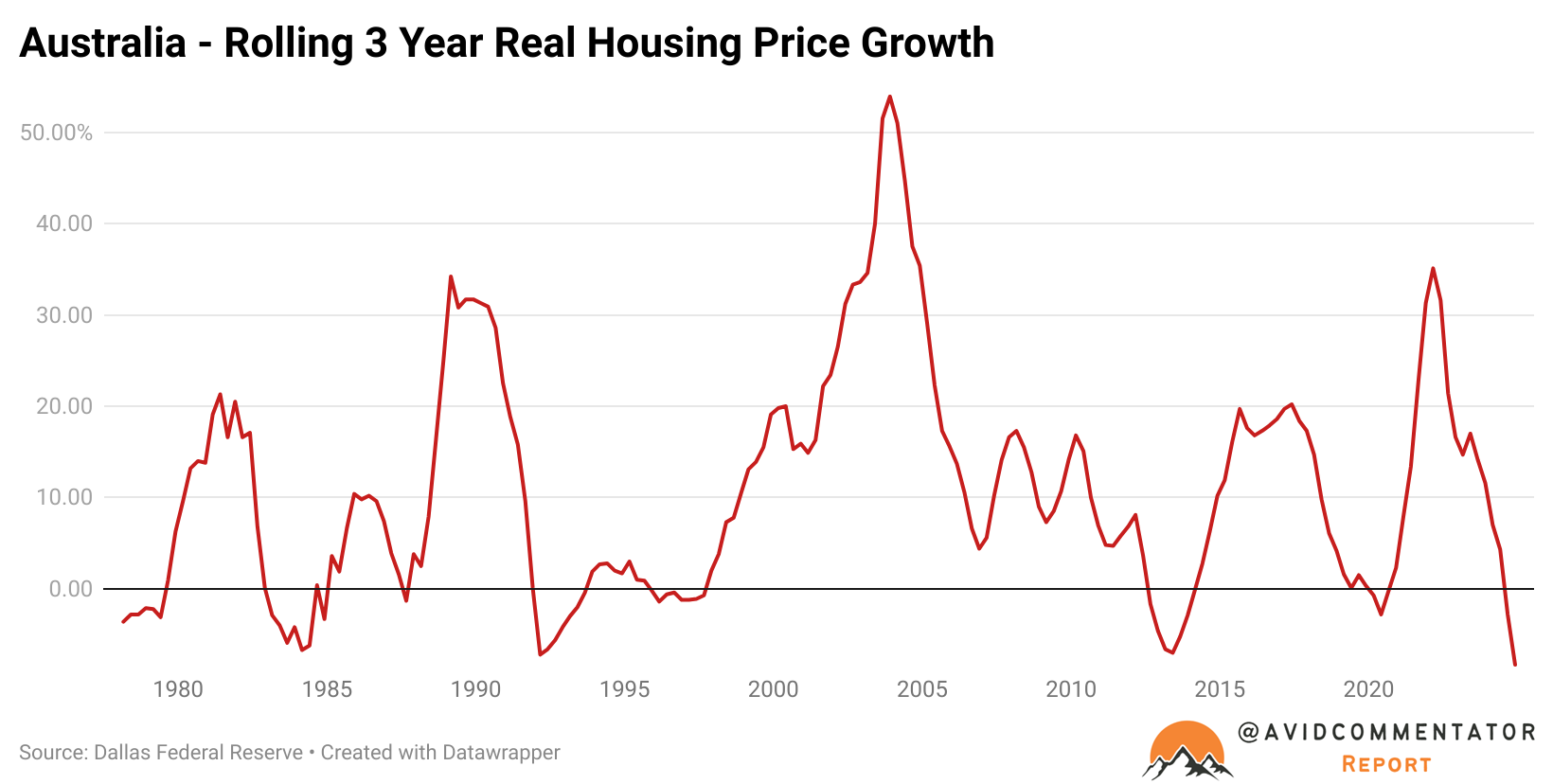

Between Q4 2000 and Q4 2003, real Australian housing prices grew by 53.9%, marking the largest deterioration in inflation-adjusted housing affordability on a rolling 3-year basis since records began in 1978.

At the time, various economists and members of the media expressed their concern about the growing unaffordability of housing.

This prompted a rather famous response from then Prime Minister John Howard:

“I don’t get people stopping me in the street and saying, ‘John you’re outrageous, under your government the value of my house has increased'”.

But despite the dramatic deterioration in access to affordable housing to buy during this era, still affordable rents would see household formation rates (as expressed by the household-to-population ratio) for the 25 to 34 age demographic continue to improve for another two years.

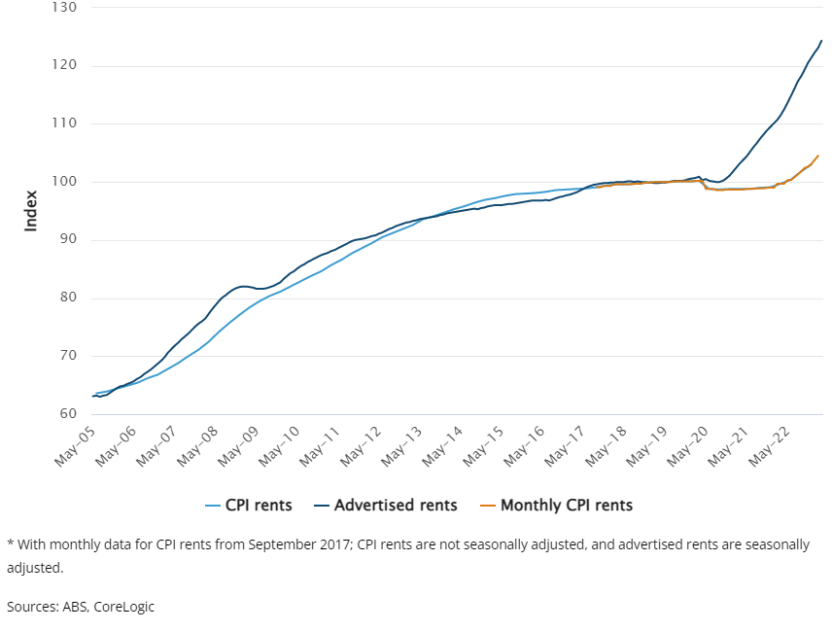

Then, with the introduction of the ‘Big Australia’ migration intake, rents began to surge, further exacerbated by an uptick in broader inflationary pressures.

Between mid-2005 and mid-2008, asking rents experienced a meteoric rise of around 30%.

Household formation rates for the 25 to 34 age demographic swiftly began to deteriorate due to the impact of higher rents and the lagged effect of higher housing prices.

This era marked the beginning of many challenges that continue to persist in the economy today.

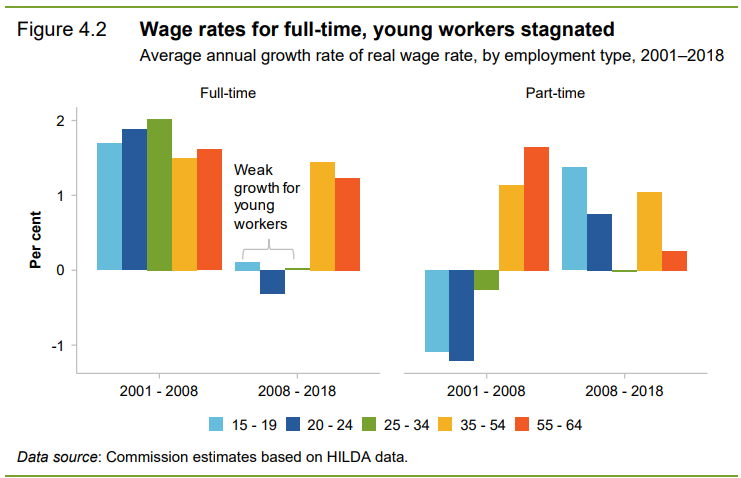

It was here that real full-time wage growth for under-35s largely stalled.

Source: Productivity Commission

Real spending for under 35s began to fall.

Despite pursuing a publicly stated policy goal of improving Australia’s demographic outlook through a higher fertility rate, the Howard government ultimately set the stage for deteriorating household formation rates, thereby creating a more challenging environment for Australians to pursue parenthood.

To be completely fair to the Howard government, policy could have been changed significantly at any time in the past 18 years to foster more affordable housing and better conditions for the formation of households and families. But the path embarked upon by the Howard government has not been deviated from.

Ultimately, Australia now finds itself only slightly removed from where Japan’s fertility rate was a decade ago.