Being a renter in Australia has turned into the Hunger Games.

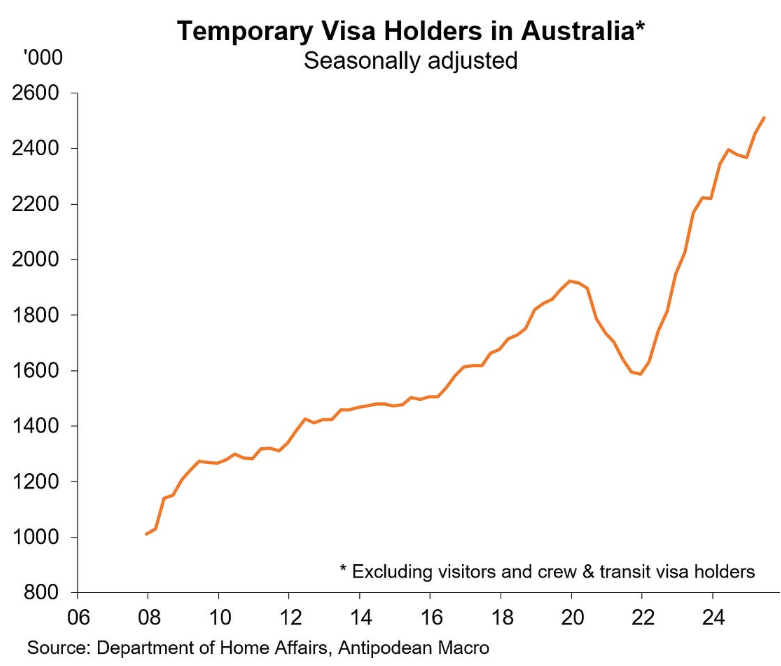

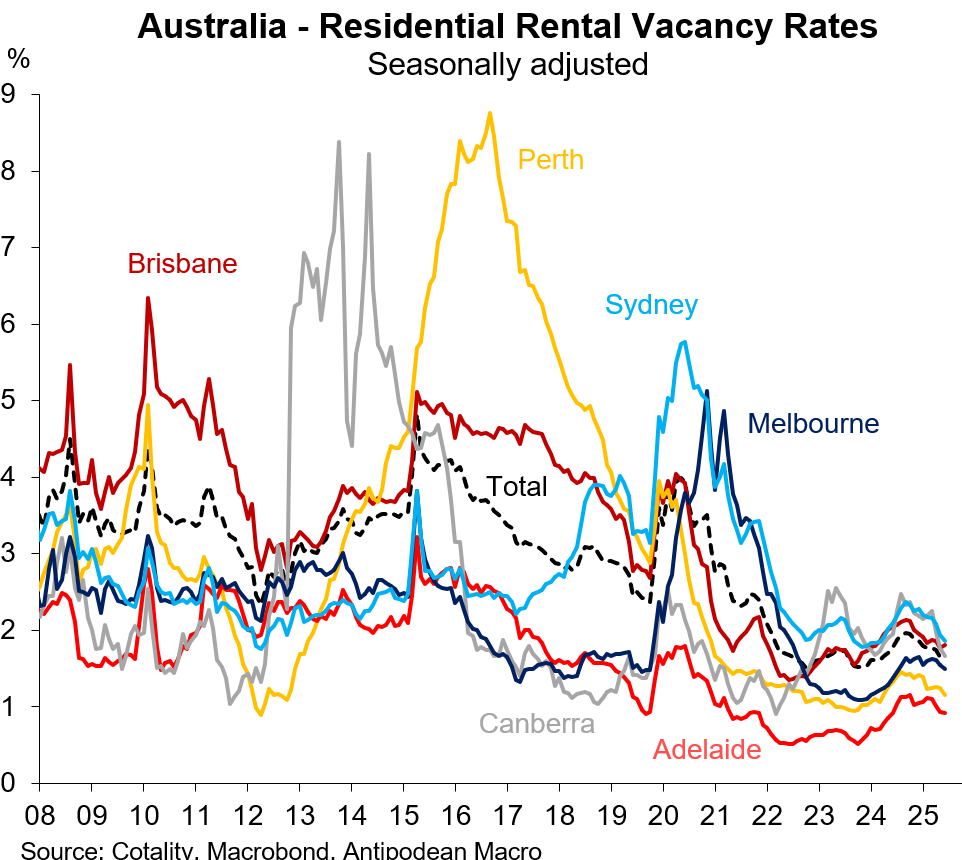

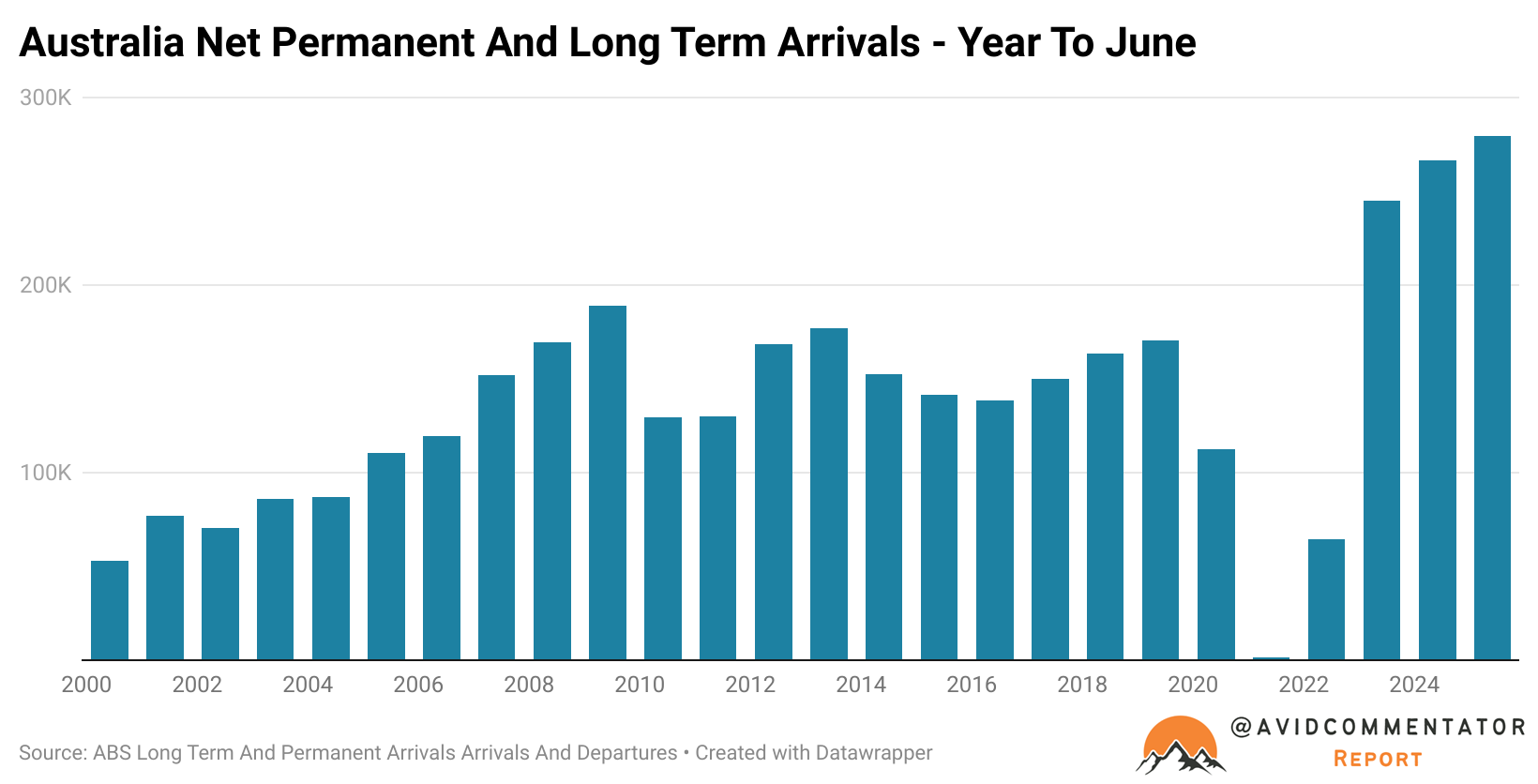

The record surge in migration post-COVID has added extraordinary rental demand, illustrated neatly below by Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro.

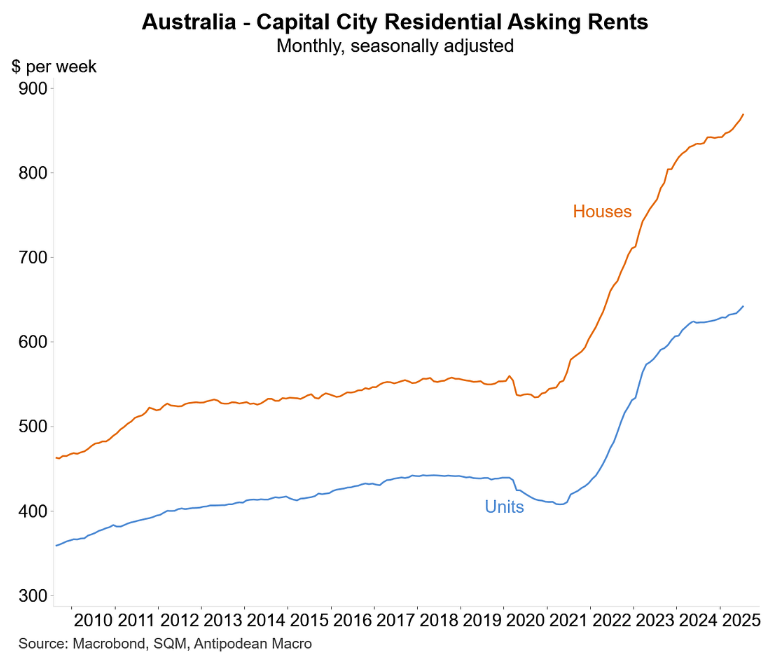

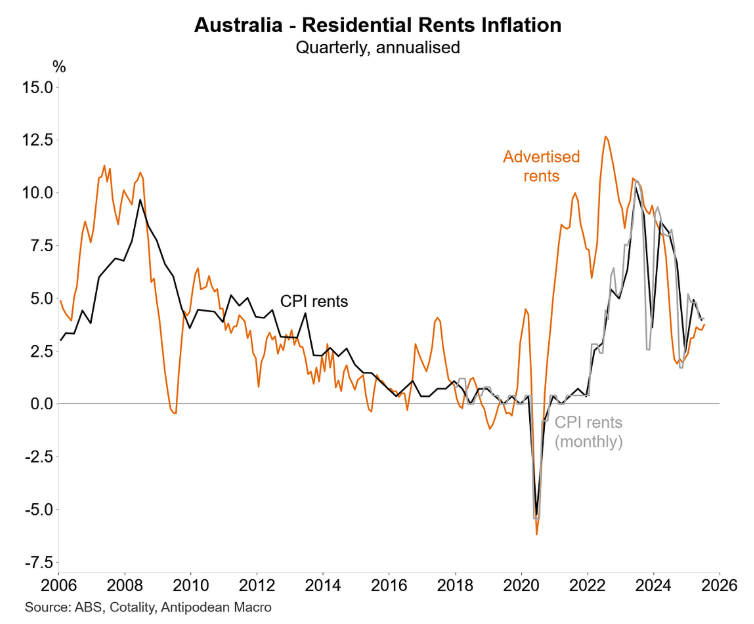

As a result, capital city asking rents soared as more people competed for housing.

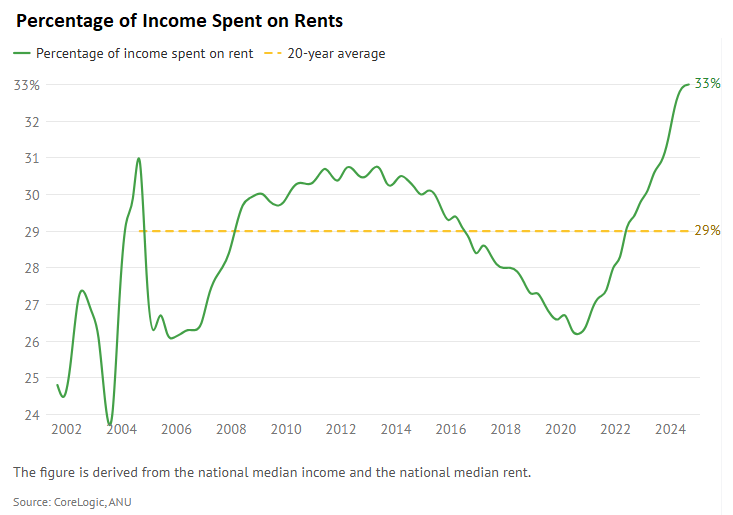

At the end of 2024, Cotality (formerly CoreLogic) estimated that rental affordability—as measured by the amount of median household income required to pay the median rent—hit a record low.

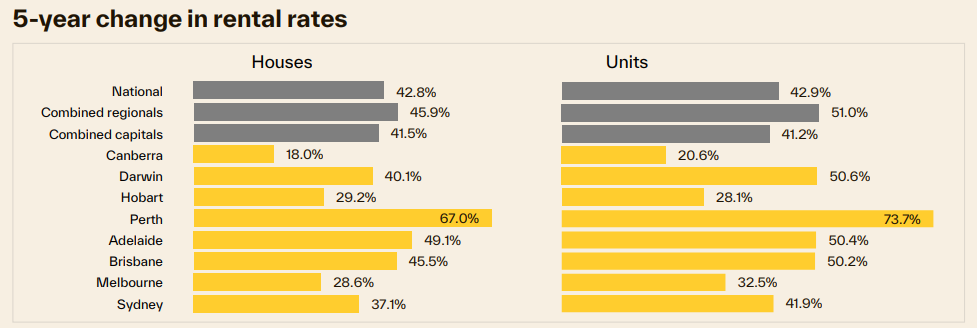

Cotality’s latest quarterly Rental Review, released in July, showed that rents nationally have ballooned by 43% over the past five years:

Source: Cotality

As a result, the national median weekly rent has risen by nearly $200 to $665 per week, adding $10,350 per year to the median rent.

After a brief reprieve last year on the back of moderating net overseas migration (NOM), the rental market appears to be retightening.

Cotality reported that rental vacancy rates have fallen back to historic lows, with the national vacancy rate standing at just 1.5% nationally in August:

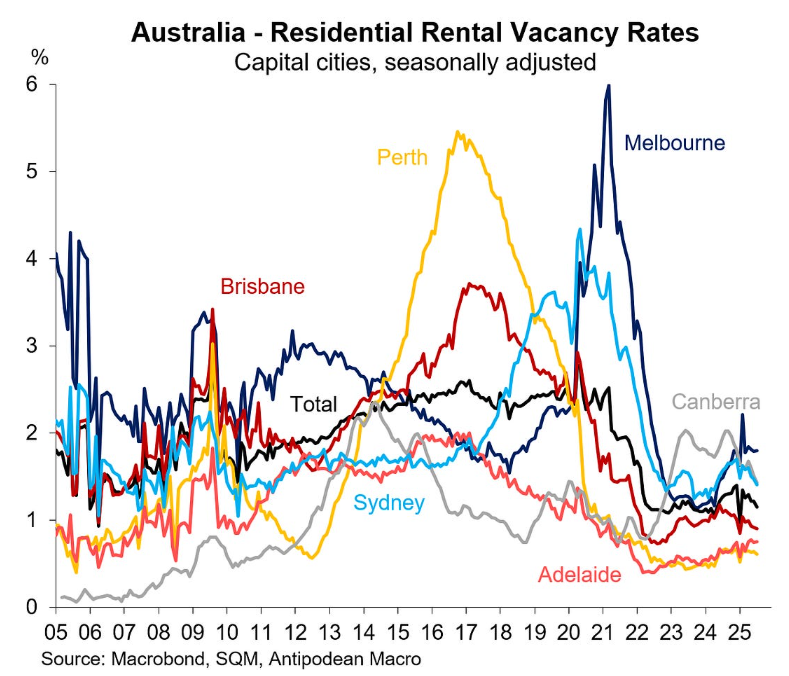

SQM Research data has also reported a decline in rental vacancy rates back to historic lows:

Meanwhile, Cotality has also reported a reacceleration of advertised rents. National rental growth rose 0.5% in seasonally adjusted terms through August, the largest month-on-month rise since May last year.

“The re-acceleration in rental growth has been apparent through most of 2025, with the annual change now rising over two consecutive months, reaching 4.1% in August”, Cotality said.

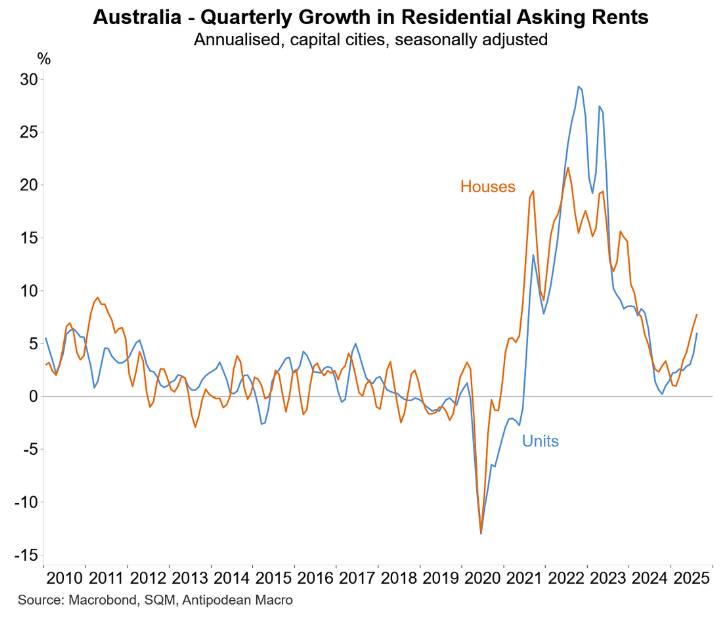

SQM Research also reported a reacceleration in asking rents:

The record surge in net permanent and long-term arrivals during the first half of 2025 seems to have tightened the rental market, as the demand from the growing population has exceeded the available rental supply.

The situation is certain to worsen in future.

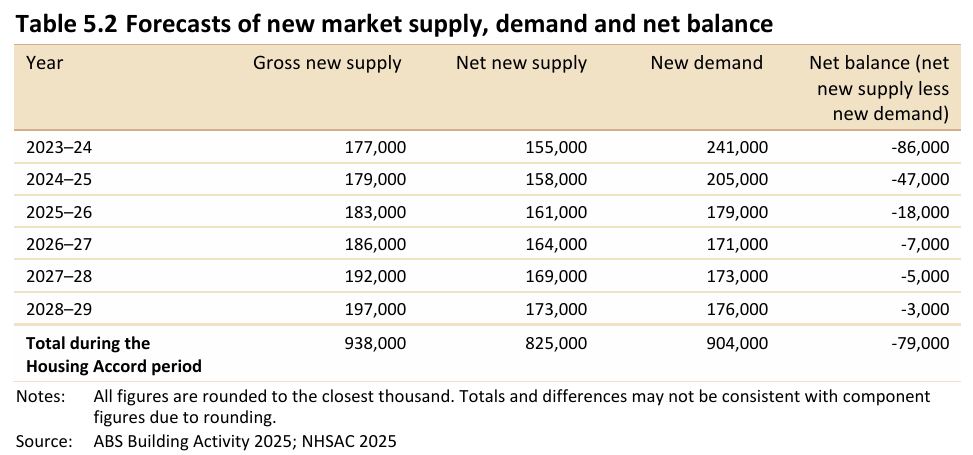

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) forecasts that new housing supply will remain below population demand over the five years to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

NHSAC warned that ongoing strong immigration relative to supply will place upward pressure on rents and result in more homelessness and overcrowding.

“The excess of new demand relative to new supply over the Housing Accord period will worsen the existing undersupply of housing in the system and add to affordability pressures”, the NHSAC report said.

“Rental housing will remain scarce for households across the income spectrum as the vacancy rate remains below its historic average”.

“A lowered vacancy rate will absorb some of the unmet demand, and some will add to the homeless population. Some may be absorbed by suboptimal types of shelter not captured by traditional measures of the housing stock, such as caravan parks, hotels and emergency shelters. Most will be absorbed by households not forming that otherwise would have, resulting in larger households and more instances of overcrowding”, NHSAC warned.

NHSAC’s projections are likely conservative given that they are based on the Australian Treasury’s net overseas migration forecasts, which are expected to reduce to 255,000 per year in 2025-26 and then 225,000 across the remainder of the forecast period.

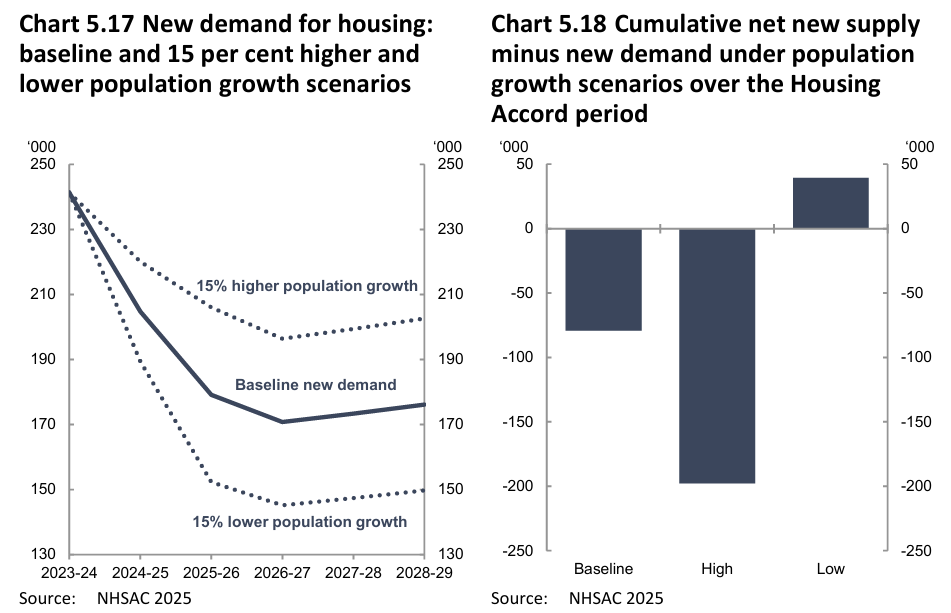

If Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, which seems likely given current immigration settings, then the projected housing shortage increases to around 200,000 over the next five years, according to NHSAC:

However, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast.

NHSAC’s modelling shows that the primary solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to reduce net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, the rental crisis will become permanent.