Australia’s rental crisis can only worsen

Seriously, who would want to be a renter in Australia?

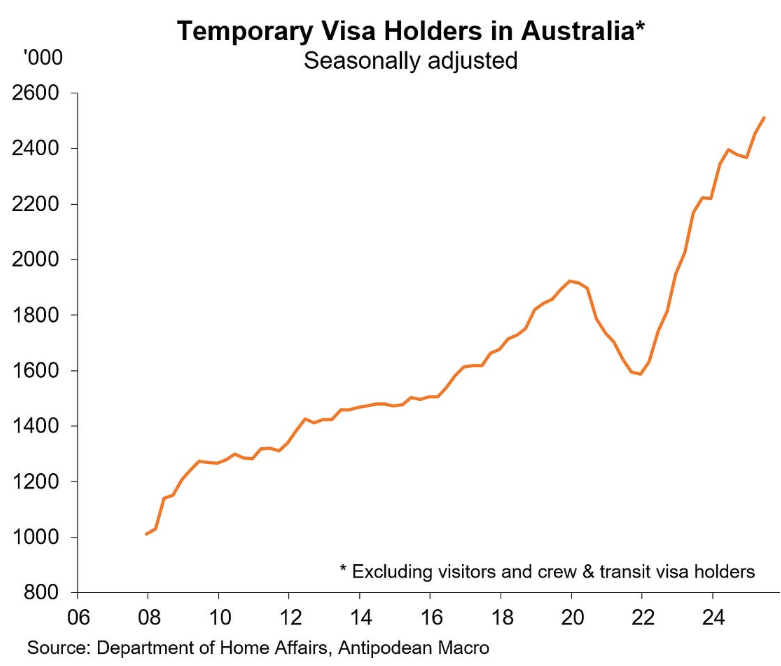

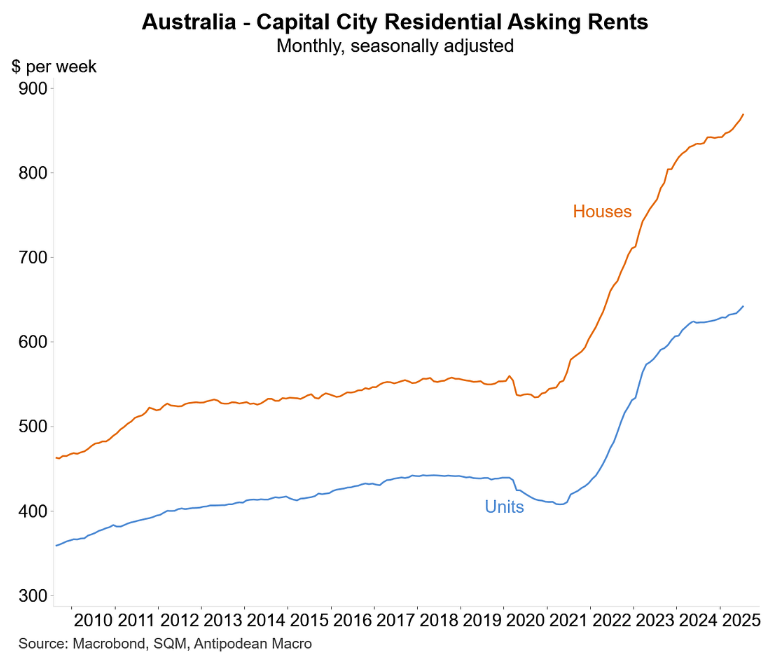

After borders reopened in late 2021 and temporary migrants flooded into Australia in record volumes, rents surged.

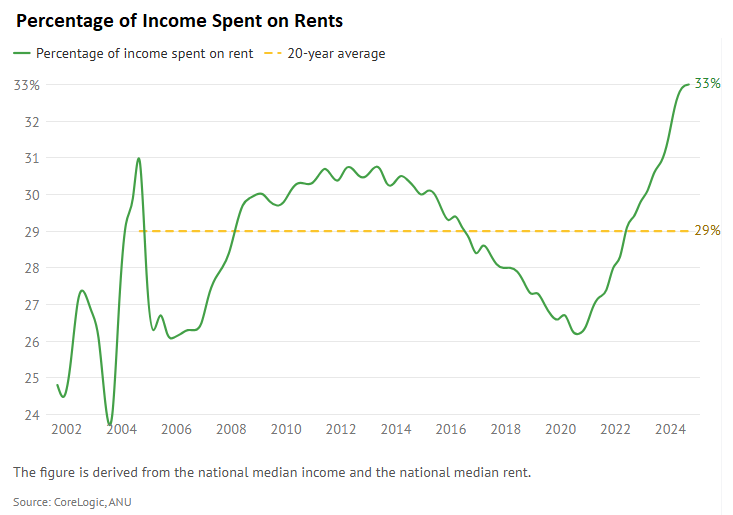

At the end of 2024, Cotality (now CoreLogic) estimated that rental payments were chewing up a record share of household income.

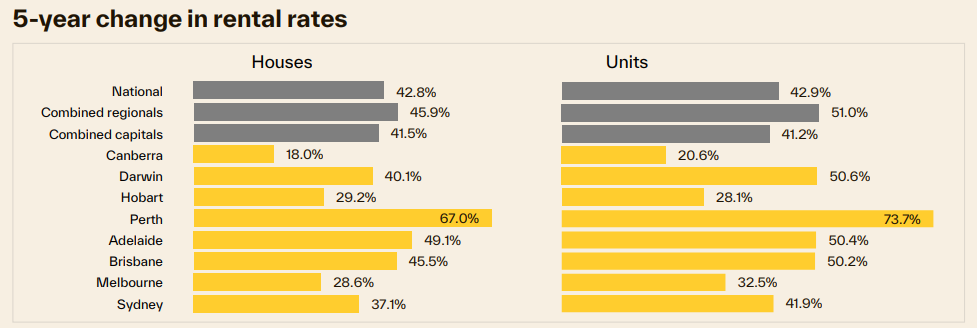

Cotality’s latest Quarterly Rental Review estimated that rents nationally have surged by $200 (43%) over the past five years, meaning that the median Australian tenant is now paying an extra $10,350 per year to rent the median home.

Source: Cotality

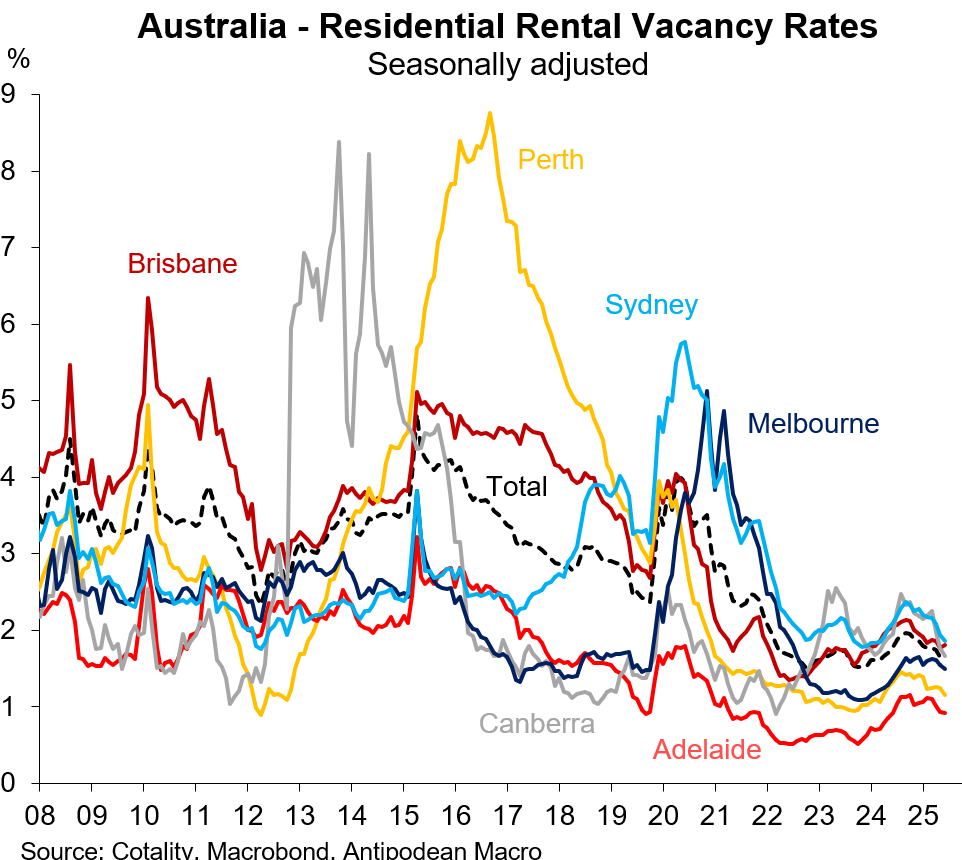

The surge in rents comes amid the decline in rental vacancy rates to historical lows.

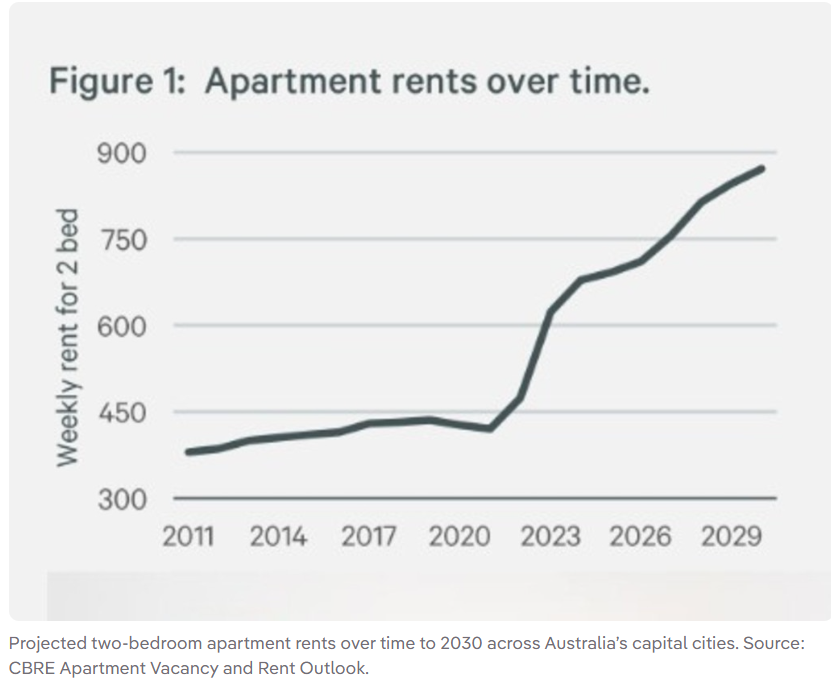

CBRE’s Apartment Vacancy and Rent Outlook forecasts that apartment supply will fail to keep pace with population growth over the next five years, driving apartment rents toward $1,000 per week.

“The result will be one in three two-bed apartments renting out for more than $1000 per week, with 92% of two-bedroom apartments forecast to have rents exceeding $700 per week”, CBRE says.

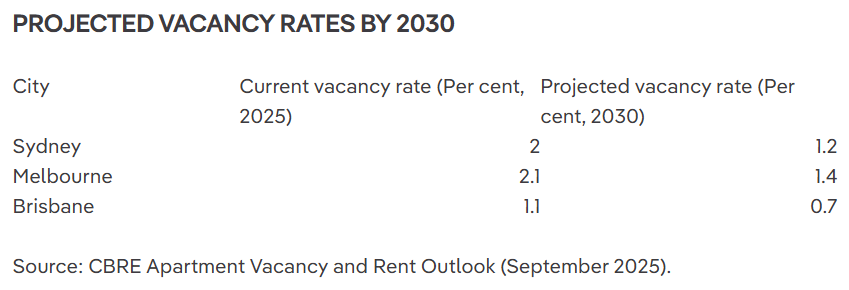

CBRE also forecasts that the national capital city vacancy rates will fall to a record low 1.1% by 2030, down from 1.8 in 2025.

The decline in the rental vacancy rate to a fresh record low will be driven by apartment supply failing to keep up with population demand.

CBRE forecasts an annual delivery of around 60,000 apartments between 2025 and 2030. This will be below Australia’s projected population growth, which will require an apartment supply of around 75,000 per year to avoid a further decline in the vacancy rate.

CBRE forecasts that vacancy rates in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane will collapse over the next five years.

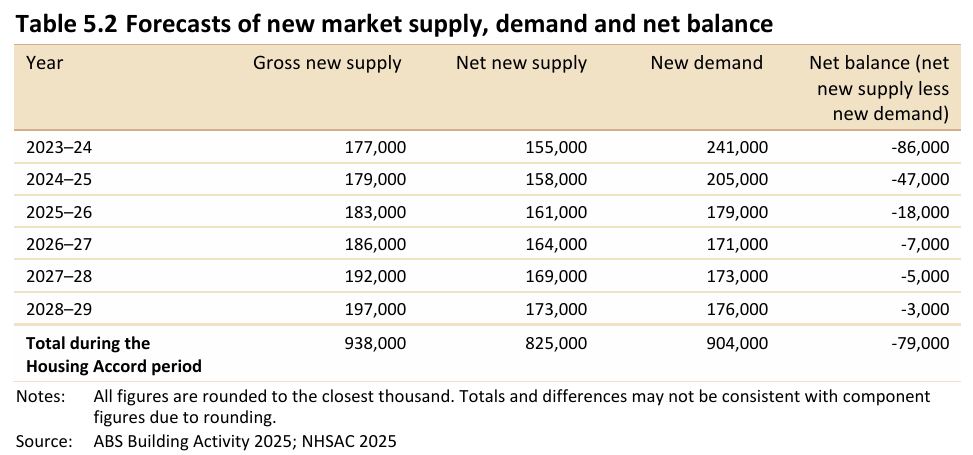

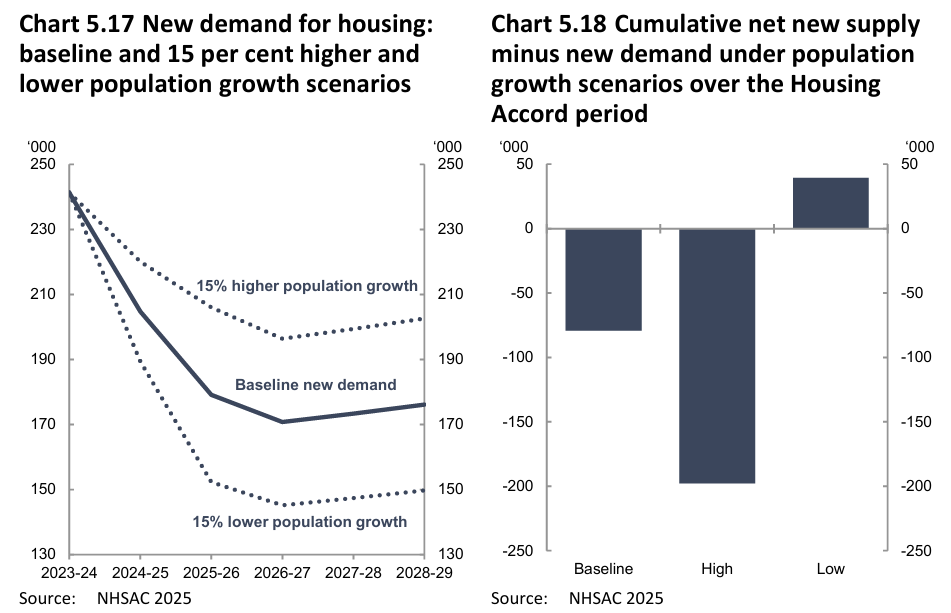

CBRE’s forecasts of a worsening rental crisis are similar to those of the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC), which forecasts that new housing supply will remain below population demand over the five years to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

NHSAC warned that ongoing strong immigration relative to supply will place upward pressure on rents and result in more homelessness and overcrowding.

“The excess of new demand relative to new supply over the Housing Accord period will worsen the existing undersupply of housing in the system and add to affordability pressures”, the NHSAC report said.

“Rental housing will remain scarce for households across the income spectrum as the vacancy rate remains below its historic average”.

“A lowered vacancy rate will absorb some of the unmet demand, and some will add to the homeless population. Some may be absorbed by suboptimal types of shelter not captured by traditional measures of the housing stock, such as caravan parks, hotels and emergency shelters. Most will be absorbed by households not forming that otherwise would have, resulting in larger households and more instances of overcrowding”, NHSAC warned.

NHSAC’s projections are likely to be conservative given they are based on the Centre for Population’s net overseas migration (NOM) forecasts. The Centre projects a reduction in NOM to 255,000 per year in 2025-26, and subsequently to 225,000 throughout the remaining forecast period.

If Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, which seems likely given current immigration settings, NHSAC forecasts that the projected housing shortage will increase to around 200,000 over the next five years:

s

On the other hand, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast.

The above forecasts by CBRE and NHSAC prove that the primary solution to the nation’s housing shortage is to reduce NOM to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, Australia’s rental crisis will worsen.