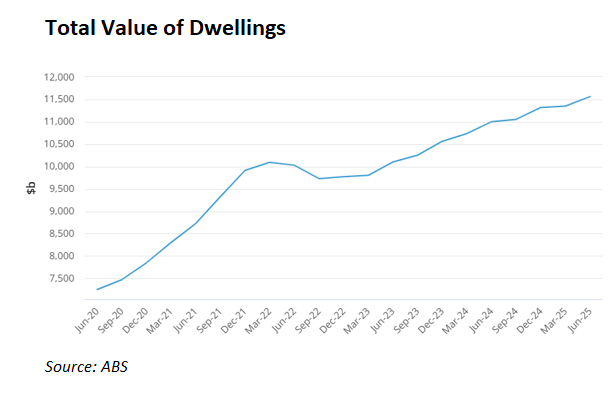

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) this week released data on Australia’s residential housing stock, which was valued at a record $11.6 trillion in the second quarter of 2025, equivalent to $1,017,000 per dwelling.

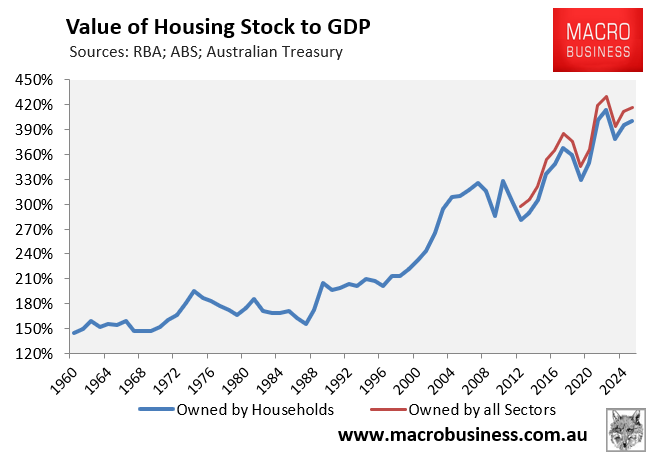

The following chart compares the value of Australia’s dwelling stock to the country’s GDP. It shows that the entire residential housing stock was valued at 4.17 times the size of the Australian economy in the June quarter:

In comparison, the United States’s dwelling stock is valued at only around 1.6 times GDP.

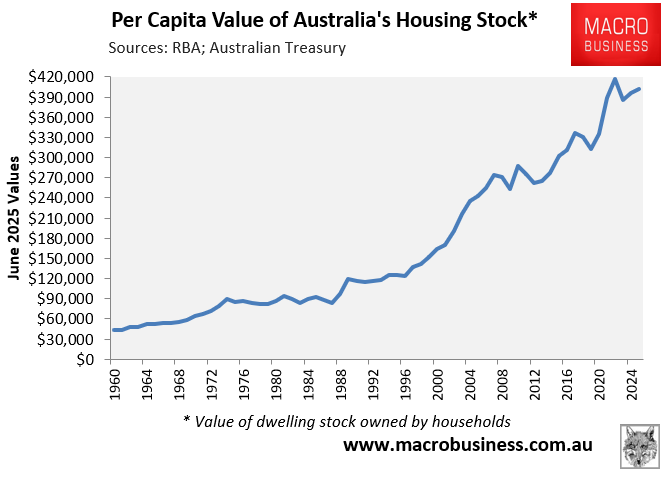

In the second quarter of 2025, Australia’s housing stock was worth $401,850 per person in real terms, and it had more than tripled in the previous 30 years.

This hyperinflation in property values helps explain why Australian households are regarded as among the wealthiest in the world, even though increasing home values is meaningless to owner-occupier households that require a place to live.

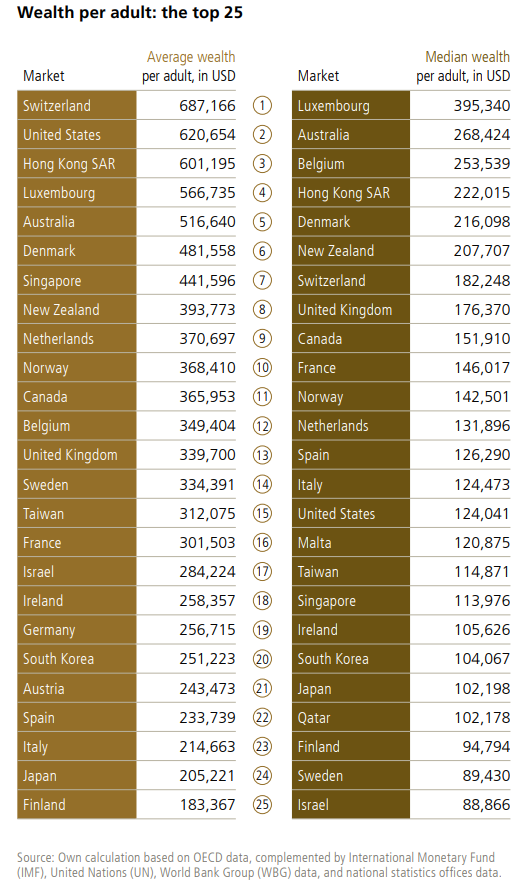

The 2025 UBS Global Wealth Report ranked Australians second in the world for median wealth, with the typical Australian worth US$268,424.

Australia had 1,904 US dollar millionaires, according to UBS.

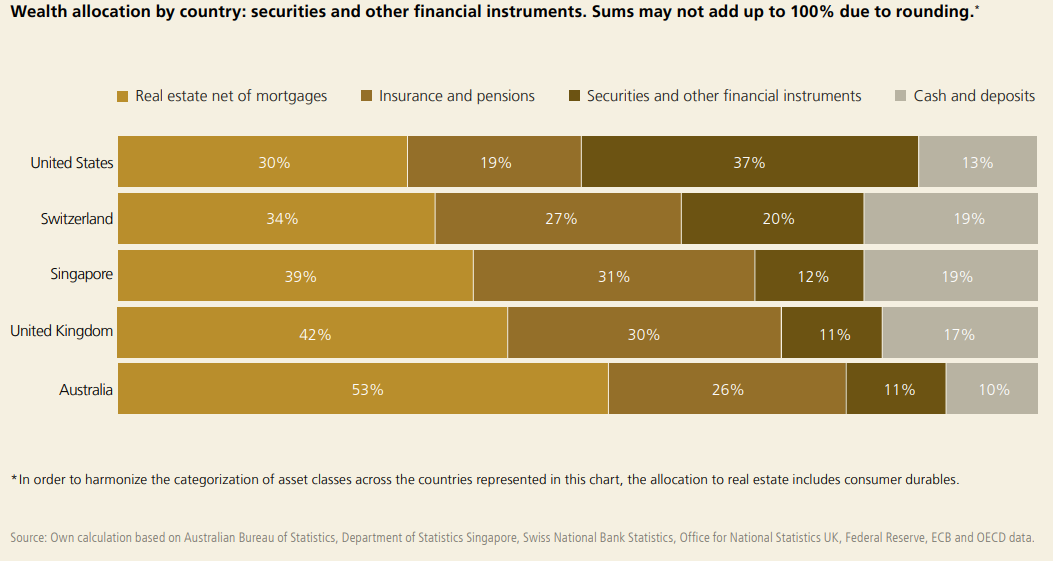

However, Australia stands apart as it stores more than half of its household wealth in illiquid residential property.

“Australia stands out for its real estate that makes up almost 53% of the country’s personal wealth, ahead of the United Kingdom and far ahead of the other markets”, UBS noted.

“In the United States, the proportion is 30%”.

“The proportion of wealth held in cash and deposits is the lowest in Australia at just above 10%, only half as much as in Switzerland, Singapore and the UK”.

Therefore, Australians are considered “wealthy” primarily due to the high cost of housing. Much of Australia’s wealth is fake, and costly housing is slowly choking the economy.

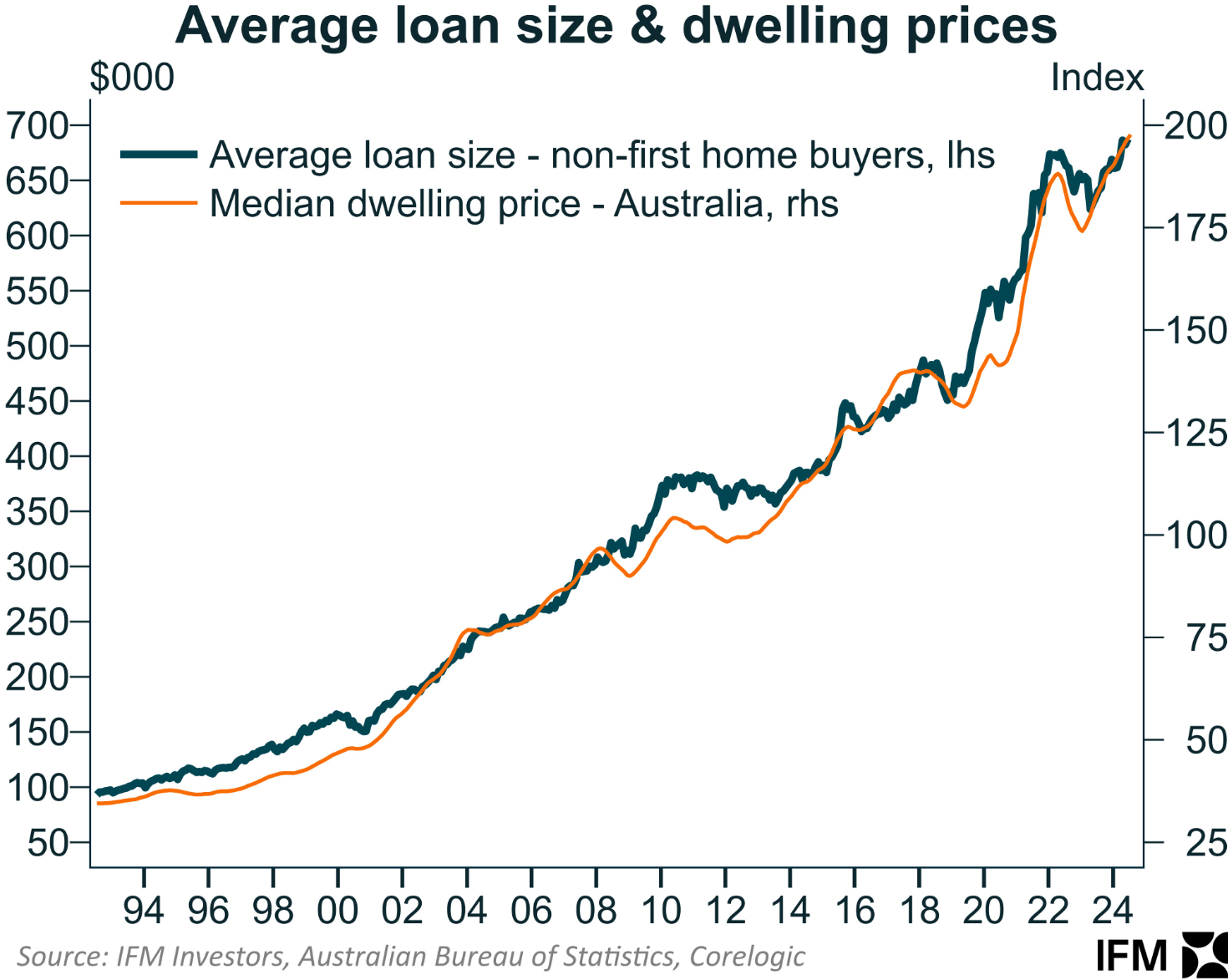

Australians are drowning in debt, taking out ever-larger mortgages to pay ever-higher home prices.

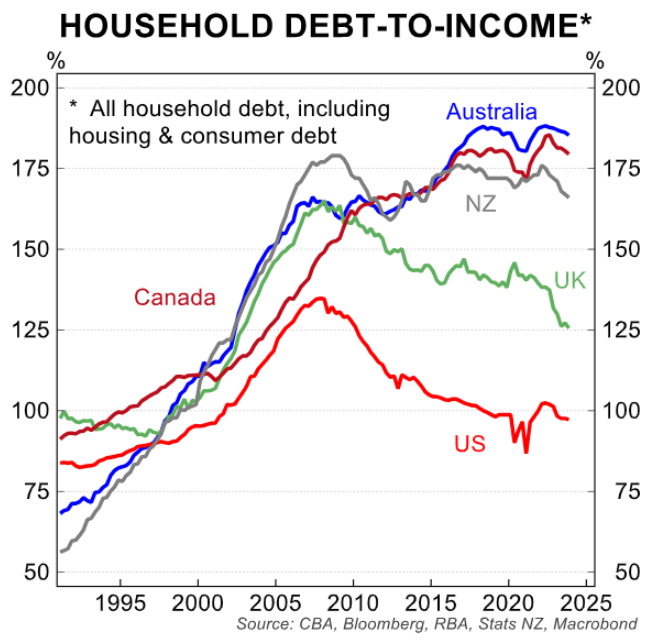

As a result, Australians carry some of the world’s highest debt loads.

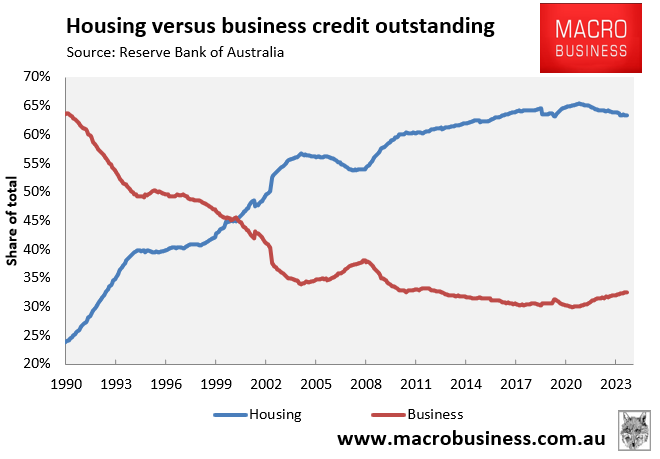

The rush of capital into housing has starved businesses of investment and lowered Australia’s productivity. Australia’s banks have disproportionately prioritised home lending over productive lending to businesses.

In 1990, roughly two-thirds of bank lending was for businesses, with mortgages accounting for only around a quarter of it. Thirty-five years later, the ratio has flipped, with over two-thirds of bank lending for housing and barely one-third for businesses.

Five of the 10 most valuable companies on the Australian Securities Exchange are banks: ANZ, CBA, National Australia Bank, Westpac, and Macquarie Group.

It’s a stark contrast to the American sharemarket, where innovative technology companies take out the top seven positions: Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google owner Alphabet, Facebook owner Meta and Broadcom.

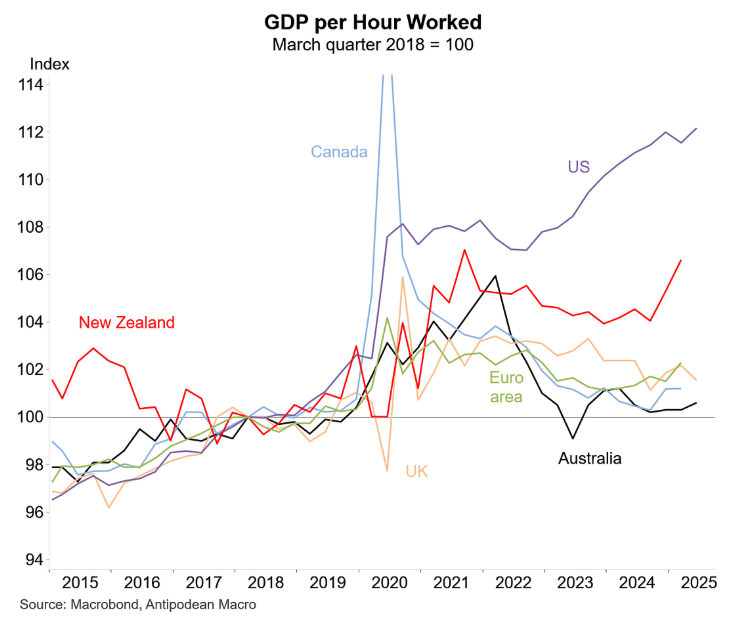

Productivity growth is booming in the tech-savvy US and stagnant in Australia.

Australia would be a considerably more egalitarian society and better off if our homes cost half as much as they do now, with half the debt.

In 1991, Australia’s home ownership rate was approximately 5% higher than it is today, homes cost about three times the average income (compared to eight times today), and household debt was 70% of income instead of the current 180%. Australia’s banks also lent two-thirds to businesses and only one-quarter to mortgages.

Australia’s economy would be more balanced and productive if it channelled capital into businesses rather than into inflating home values.

In this regard, Australia’s $11.6 trillion housing stock is a gross misallocation of capital.

Regrettably, from next month on, the Albanese government will allow all first-time home buyers to purchase a property with only a 5% deposit, with the government (taxpayers) guaranteeing 15% of the borrower’s loan.

Labor’s policy, combined with lower interest rates, will further increase household debt and property prices, as well as divert more of the nation’s capital into unproductive housing.