Australian universities are poorly run black holes

Australia’s universities are among the nation’s most poorly run organisations.

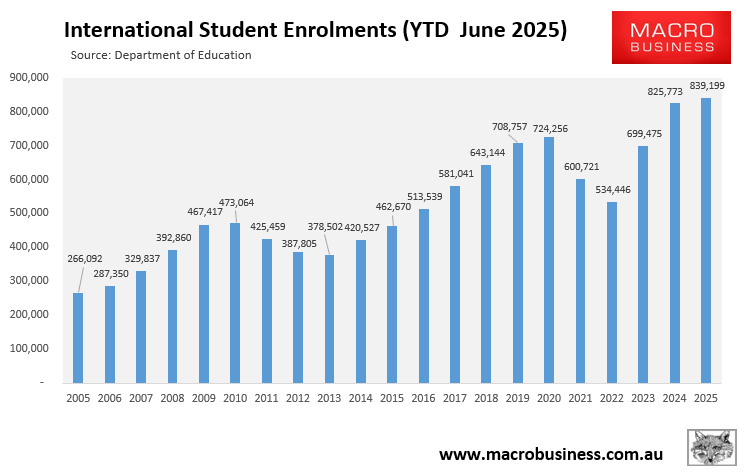

The number of international enrolments hit a record high of 839,200 in the year to June 2025. This was up around 13,400 (1.6%) from the 825,800 enrolments in 2024, around 130,440 (18%) higher than the same time in 2019 before the pandemic, and more than triple the 266,100 enrolments 20 years earlier in 2005.

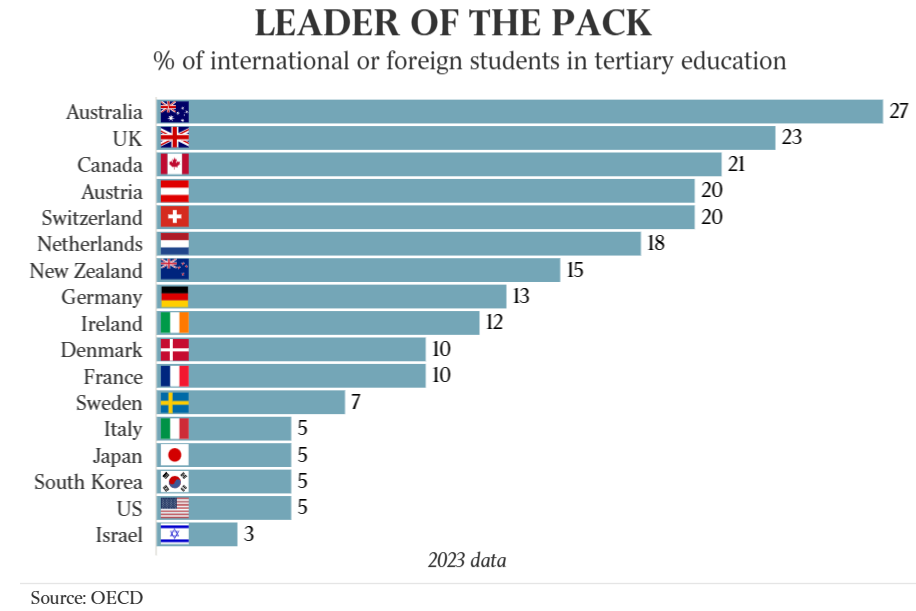

Australia’s universities also have the second-highest concentration of international students in the world after Luxembourg:

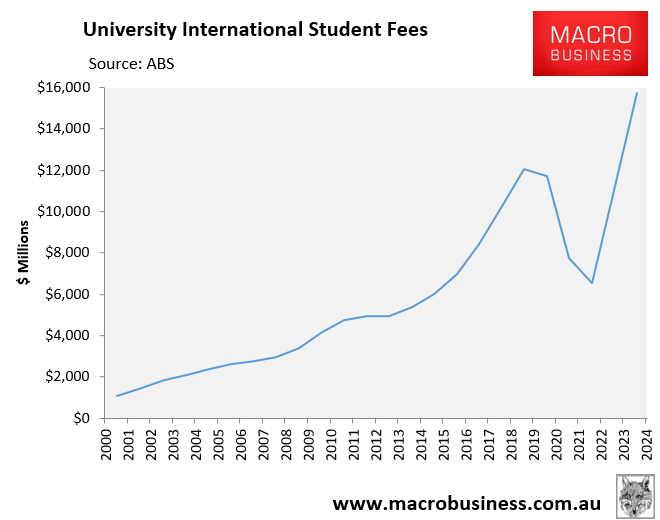

As a result, fees paid by international students at Australia’s universities hit a record high of $15.7 billion in 2023-24, according to the ABS.

The $15.7 billion of international student university fees earned in 2024 was almost triple the $5.4 billion earned a decade earlier in 2014.

Despite the record international enrolments and fees, the university sector continues to struggle financially. As reported by AFR education editor Julie Hare in April, one quarter of Australian universities have implemented cost-cutting measures:

“Thousands of jobs [are] on the chopping block as their finances reel from falling student demand and anti-migration policies”.

“The combined effect of restructuring efforts at nine universities will slice about $650 million from budgets and mean the loss of at least 2,200 jobs”.

Salvatore Babones, an Associate Professor at Sydney University and author of the book Australia’s Universities: Can they Reform?, penned an article in The AFR lambasting Australia’s public universities for running deficits “even as their revenues have expanded at double-digit annual rates”:

All eight Group of Eight universities aspire to be placed in the global Top 100 on the international rankings, and the other 30 public universities want to shine, too.

Those aspirations have led them to enrol staggering numbers of international students at an enormous cost to society in terms of housing affordability, overcrowding, stalled productivity growth and the lack of social integration.

Australia’s international student numbers are so large that they even warp our understanding of international statistics.

When the international accounts were set up, no one envisioned that an entire national university system would be reoriented toward serving international students. Australia has shown the way. Even the much-ballyhooed international student caps won’t change that. They will only slow the growth in international enrolments.

Incredibly, more than half of Australia’s public universities still manage to run deficits. Even as their revenues have expanded at double-digit annual rates, their appetites have grown even faster.

The reality is that Australia’s universities are struggling financially due to poor management and waste.

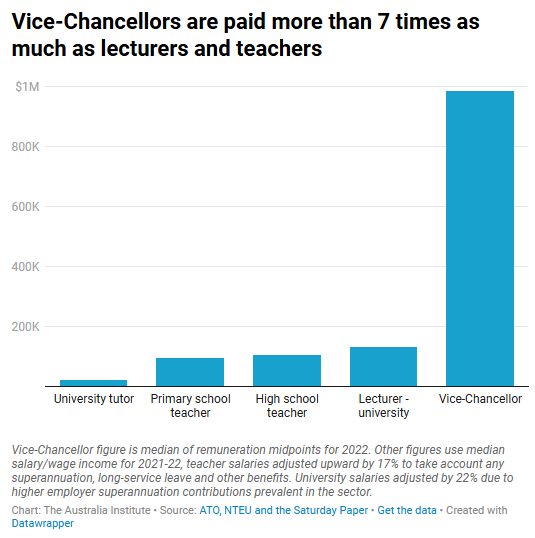

Vice-chancellor salaries in Australia are the highest in the world and far exceed those of other educational professions.

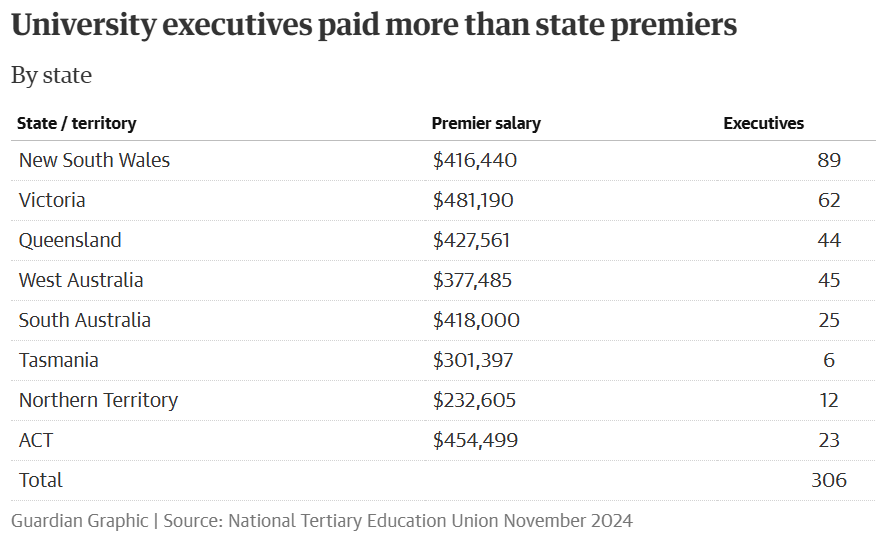

Over 300 Australian university CEOs earn more than state premiers.

Meanwhile, university wage theft is rampant, with institutions underpaying employees by more than $400 million nationwide.

The truth is that policymakers collaborated with the education sector to develop a system that rewards university executives with massive salaries for transforming their institutions into low-quality, high-volume immigration mills.

- The Australian government provides generous work rights for students and opportunities for permanent residency.

- To attract international students, Australian institutions relaxed their entry and teaching standards.

The funding windfall has been wasted by management, with universities crying poor and protesting nonexistent migration cuts.