Earlier this month, Ex-NSW Senior Trade and Investment Commissioner for Japan and Korea Michael Newman lambasted the size of Australia’s bureaucracy, claiming we had one of the world’s largest number of public sector workers per head of population.

Newman claimed that Australia has 140 public servants for every 1,000 people. By comparison, Japan has 38 per 1,000 people.

“We employ 2.5 million bureaucrats in Australia, costing us $232 billion a year. Japan, with five times our population, runs on 3.3 million bureaucrats and spends only $270 billion”, Newman reportedly said in his speech.

“17% of the working age population in Australia is now on the government payroll. In Japan, it’s not 17% or 15% or 10% or 8%, it is just 5%”.

“Our bureaucrats are on bigger salaries too. Per head, Australian public servants earn an average of $93,000 versus Japan at just $76,000. At the senior executive level, federal heads of department in Australia are raking in up to a million Aussie dollars a year”.

Newman described the number of public sector workers as “self-sabotage on an industrial scale”.

Newman also took aim at the Albanese government, which has increased the size of the bureaucracy at an additional cost to taxpayers of $50 billion every year, almost as much as the nation spends on defence. Meanwhile, actual outcomes for taxpayers are worsening.

Economist Manning Clifford has raised similar concerns on his Cliffhanger Substack site, arguing that “Australia has become a staffer state”.

“The top set of decision makers in our society spent their formative years as political staffers, rather than in other roles”, Manning argues. “The impacts of this are non-trivial and worthy of reflection”.

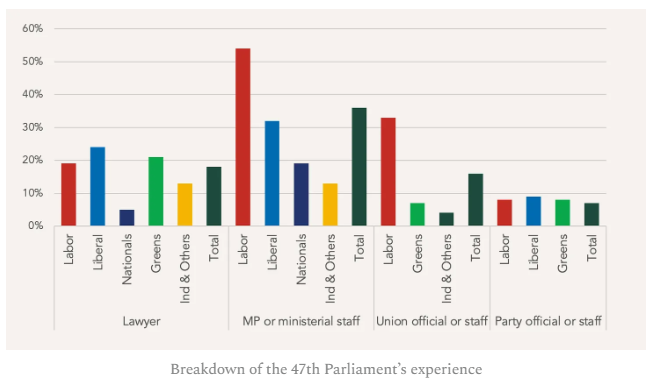

He cites analysis from Per Capita, which “found that nearly 40% of all parliamentarians were political staffers before entering parliament (this is 10x what it was in 1988, when it was 3.6%), with even more in party positions”.

“This is particularly the case among the Labor party: around 50% of Labor MPs in the 47th Parliament were previously staffers (up from 3.4% in 1988); an additional 8% or so were party officials or staff”.

Clifford notes that most Prime Ministers and senior cabinet officials during his lifetime were ex-political staffers.

“Those in power prefer those they already know, and those who already know understand how to work the system”, he writes. “Decisions are increasingly centralised in leaders’ offices and party HQs”.

Clifford lists three main negatives from having a staffer-led nation:

- It encourages short-termism and overconsultation. “To an ex-staffer, every policy issue looks like it can be solved with a roundtable”.

- It leads to policy shallowness and flashy announcables. “A parliament of ex-staffers risks reproducing the weaknesses of ministerial offices: excessive reliance on briefing notes, rather than a fundamental understanding of how parts of our society function”.

- It can lead to an erosion of trust and representation. “Voters can smell when politicians have lived or flown too and from Canberra their entire careers. The sense that MPs are “party creatures” rather than “representatives of the people” corrodes legitimacy”.

In my opinion, Australia has become too reliant on government, which interferes too much in our lives.

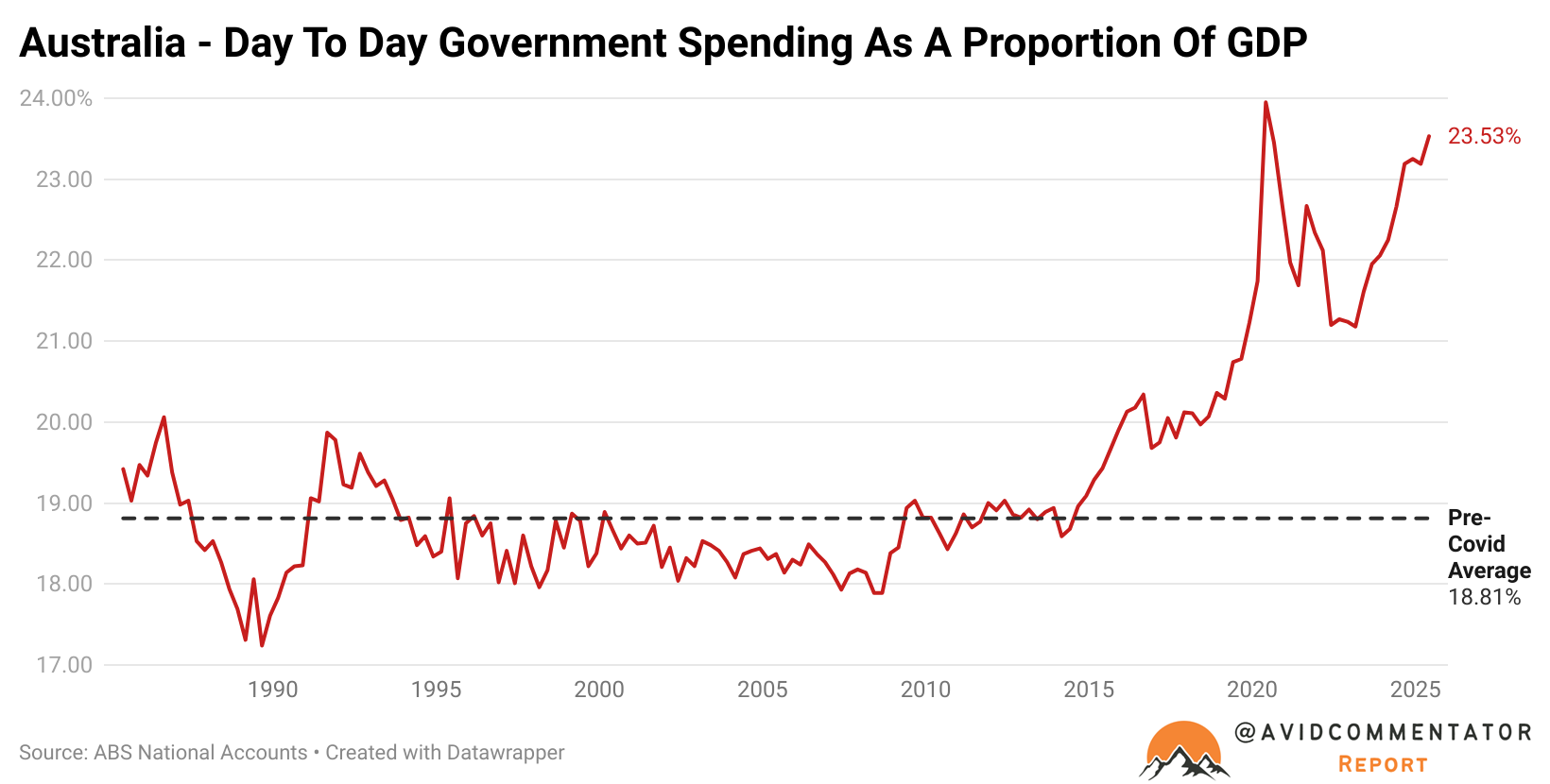

Day-to-day government spending as a share of the economy is far too high:

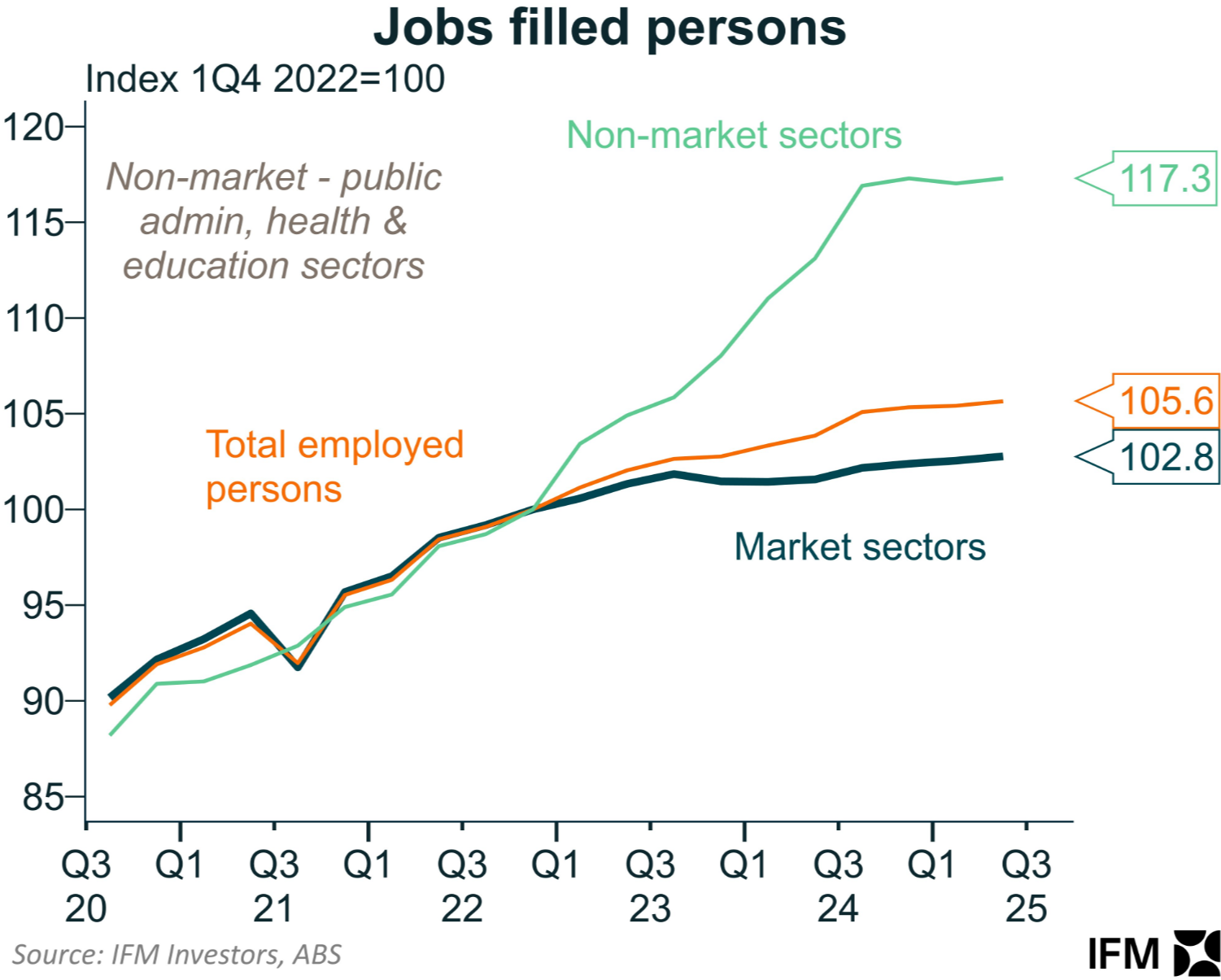

Too many jobs in Australia are government-funded in the non-market sector:

And government censorship and overall interference in our lives are too high.

The end results are less personal freedom, lower productivity growth, and lower living standards.