The solution to the rental crisis is being played out across Australia’s two most similar nations: Canada and New Zealand.

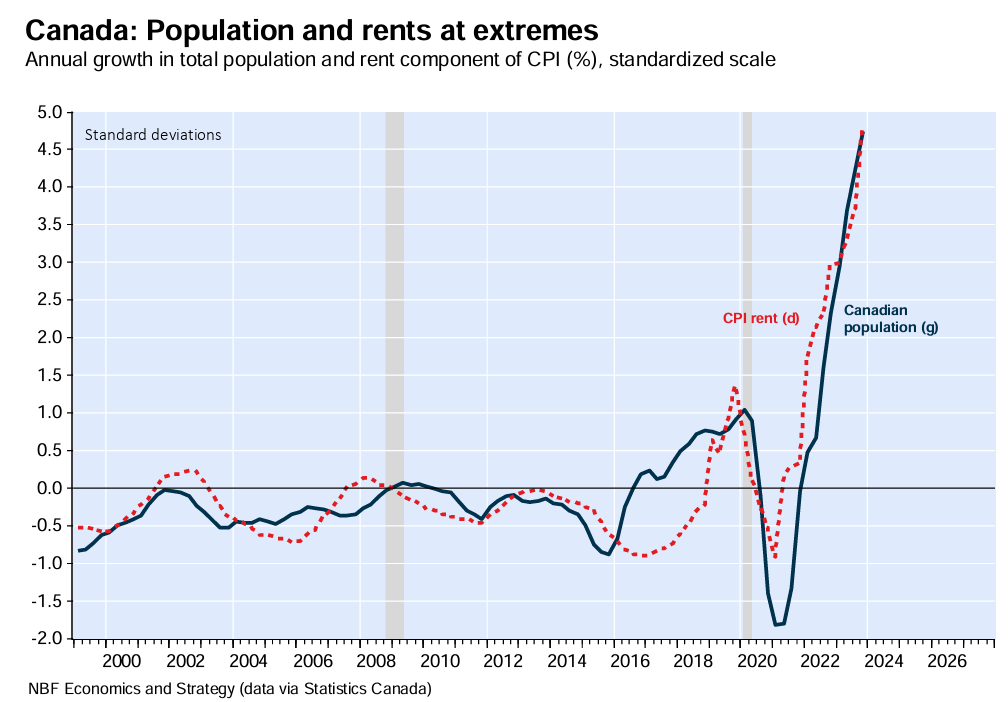

Canada experienced a record rise in rents in response to the largest surge in immigration in the nation’s history.

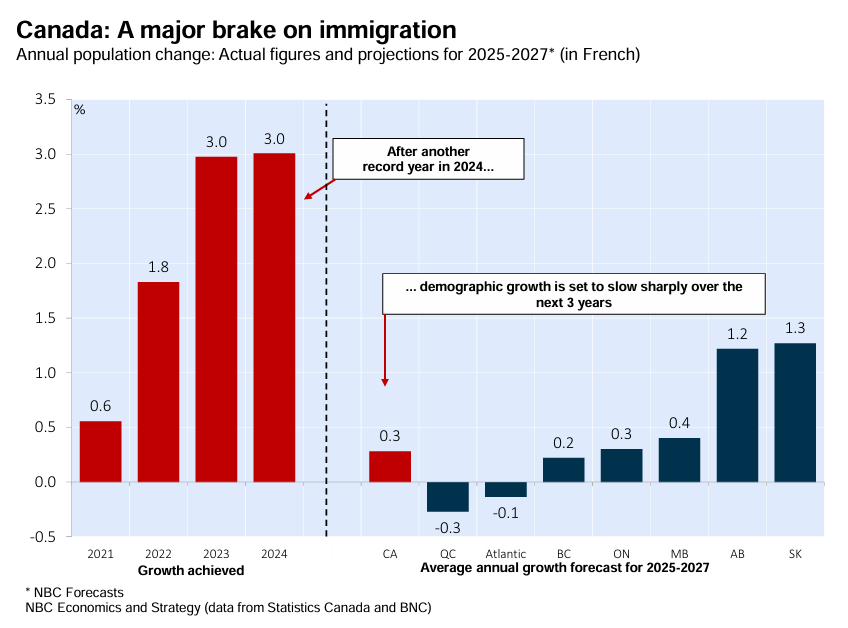

Last year, the Canadian government announced that it would freeze population growth for three years in a bid to relieve pressure on the housing market and infrastructure.

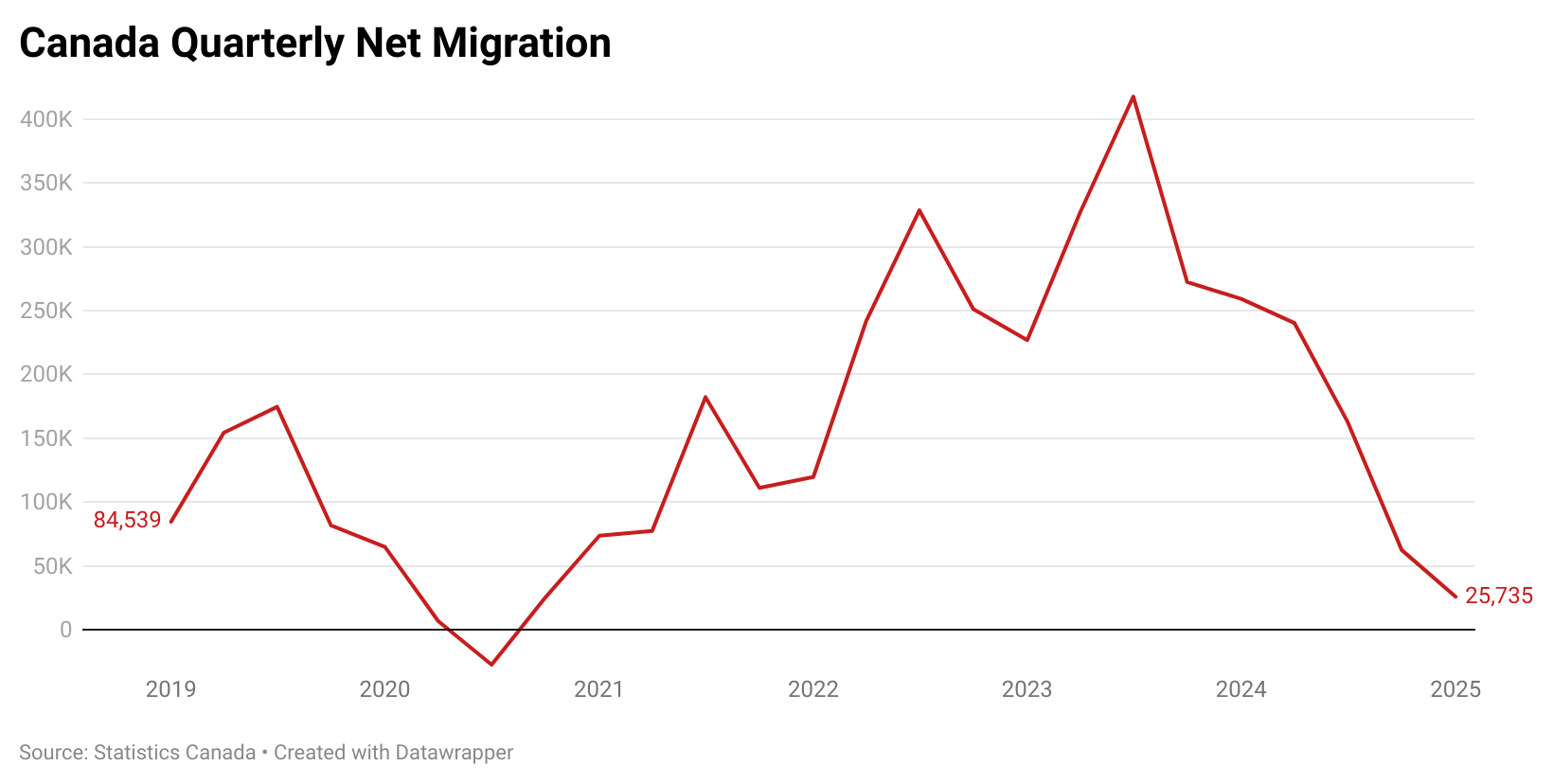

The plan has worked, with nearly 210,000 temporary migrants either leaving Canada or transitioning to permanent residency in Q1 2025.

Canada’s net migration has plumetted by over 90% compared from its 2023 peak. Compared with its final pre-pandemic reading of the same quarter, net migration has fallen by over two-thirds.

The impact on the housing market has been instantaneous.

Canada’s largest bank BMO reported that “rents are now declining in more than half of Canada’s 40 Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) from a year ago”.

“This marks a notable change from the recovery period after the pandemic when fast growing wages and large inflows of international arrivals supercharged demand for Canadian housing, including rental”.

“Affordability constraints, decelerating population growth, and increased rental supply have collectively helped rebalance rental market dynamics in recent quarters”.

“Cities in British Columbia and Ontario—historically major destinations for non-permanent residents—have been disproportionately affected by immigration cuts, which has contributed to a sharp slowdown in population growth in these provinces. That’s helped ease housing demand while rental supply continues to build, fostering softer rental market conditions compared to other regions”, BMO noted.

BMO added that rents should continue to fall as “stricter immigration targets continue to slow population growth and limit new household formations”.

The latest monthly report from Rentals.ca and Urbanation also noted that the national average asking rent in July fell 3.6% from a year earlier to $2,121, marking the 10th consecutive month of year-over-year decreases.

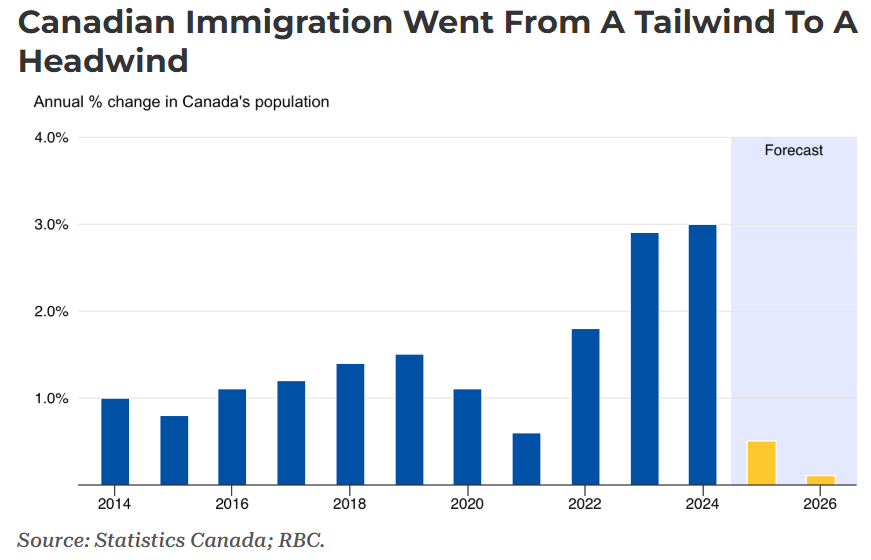

Separately, BMO forecasts falling home prices next year, with immigration transforming from a tailwind to headwind for the housing market.

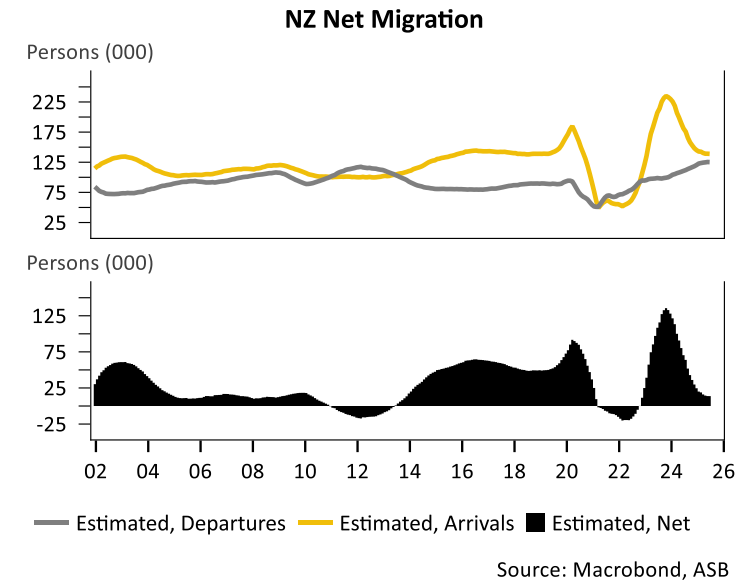

New Zealand is experiencing similar outcomes amid a decline in net overseas migration to fresh 2½-year lows in July.

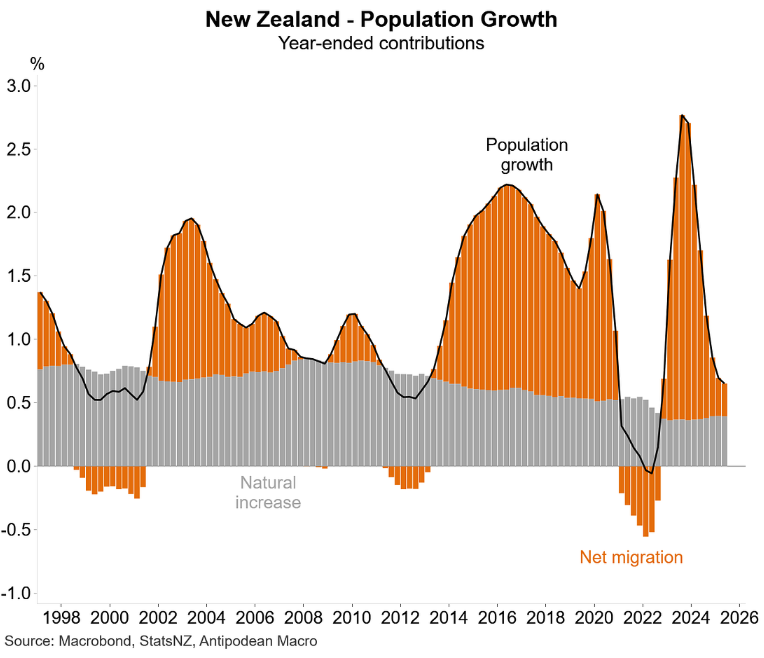

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, “New Zealand’s population grew just 0.65% over the year to Q2 2025, with less than 0.3ppts of that growth coming from net immigration”.

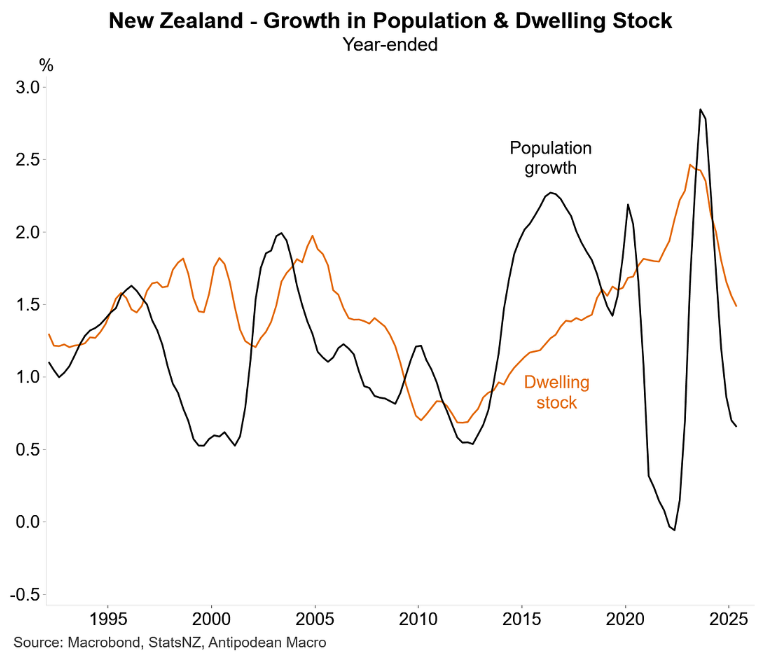

As a result, housing construction is now running well ahead of population demand.

Major bank ASB noted that “easing net immigration inflows have further exacerbated the imbalance between housing demand and supply”, dampening both rents and prices.

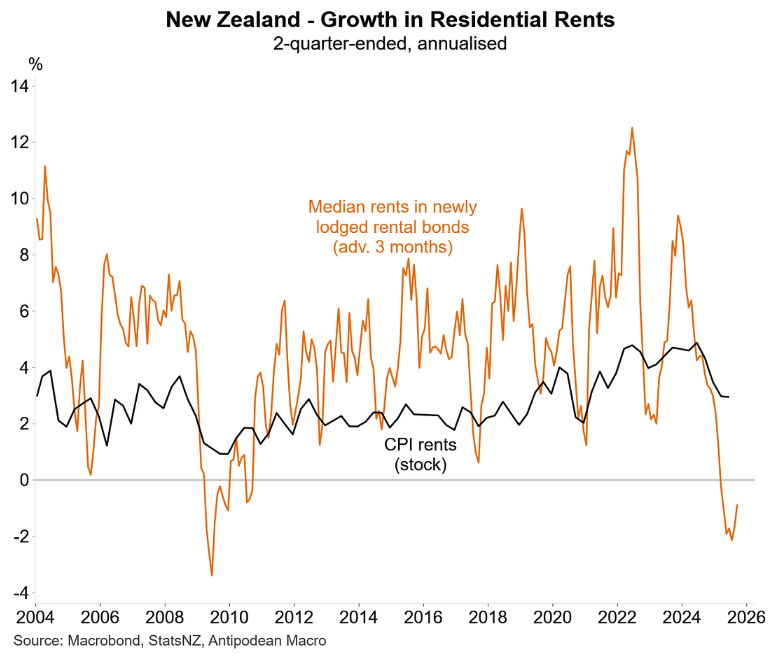

Indeed, median rents in new residential rental bonds have fallen over the past year or so.

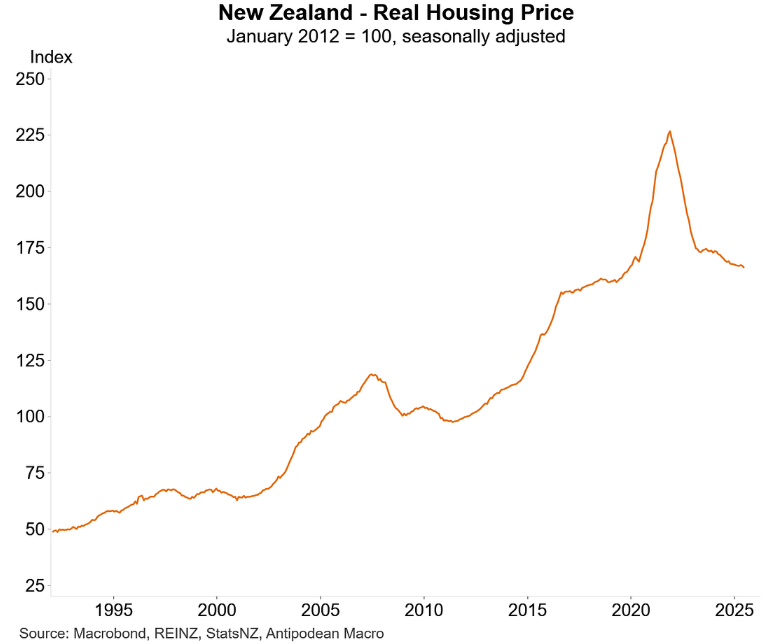

New Zealand real house prices, which are less sensitive to changes in net migration, have also plummeted:

The key takeaway is that if policymakers genuinely want to ‘solve’ the rental crisis, then they need to cut immigration to sensible and sustainable levels below the capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

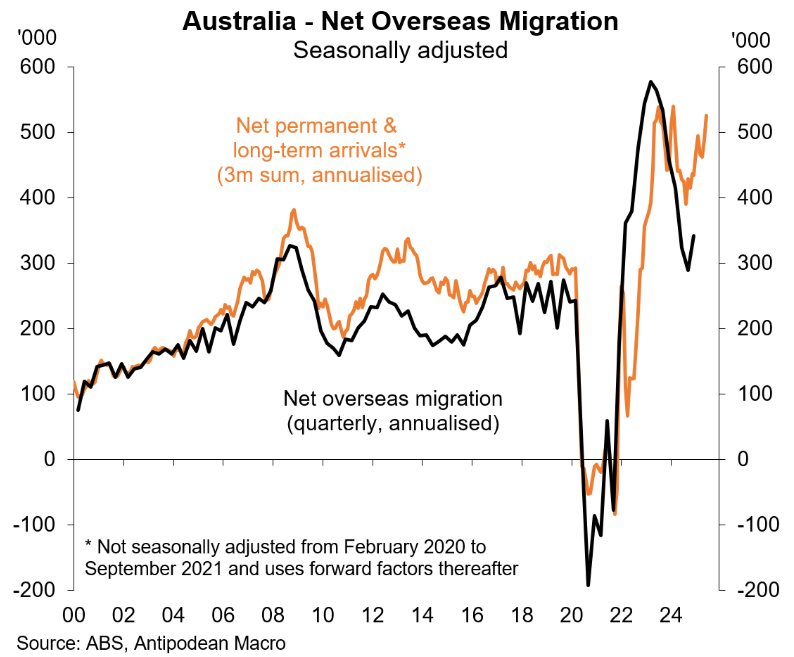

Sadly, Australia has taken the opposite path, reigniting another immigration boom.

The Albanese government has stupidly lifted the intake of international students by 25,000 and watered down English-language proficiency rules.

As a result, Australia’s international student and temporary visa numbers—which are already the highest in the advanced world relative to our population—will inevitably increase.

Australia’s rental crisis will also worsen as demand continues to overwhelm supply.