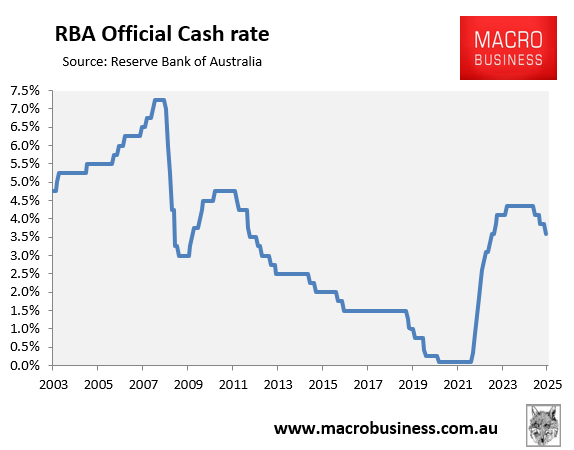

On Tuesday, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut the official cash rate (OCR) by 0.25% to 3.60%.

The RBA has now cut the OCR by 0.75% from its peak of 4.35%, and most economists and financial markets expect another two rate cuts to be delivered by mid-2026.

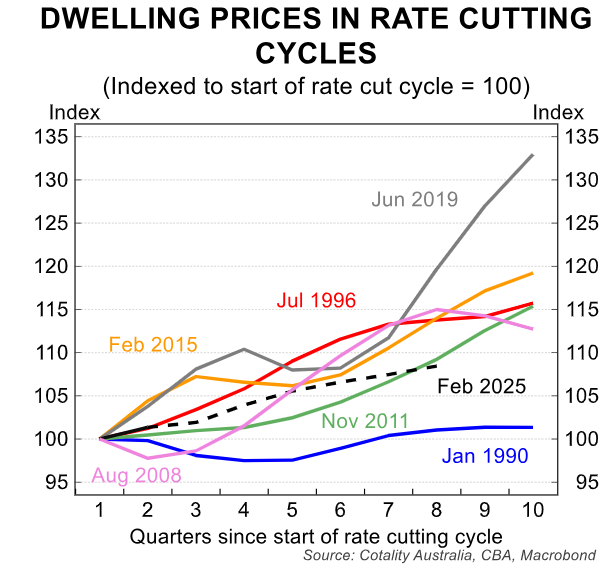

The following chart from CBA shows that dwelling values generally rise by double-digit rates in response to a rate-cutting cycle.

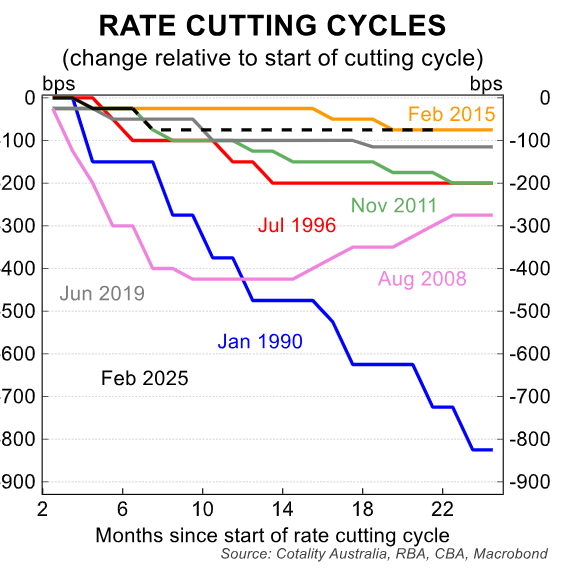

However, Cotality cautioned that any rate relief will be shallow and will likely leave monetary policy in neutral rather than stimulatory territory:

“Although rates are coming down, they are doing so from a high base, and monetary policy settings remain in restrictive territory”.

“Even if interest rates decrease by another 50 basis points to 3.1%, the cash rate would only be around neutral territory. Prior to the pandemic, the decade average cash rate was just 2.55%”.

While the current rate-cutting cycle is forecast to be relatively shallower than prior episodes, which should dampen any price rise, they will also be accompanied by stimulatory policies from governments.

In particular, from 1 January 2026, the Albanese government will allow first home buyers to purchase homes with only a 5% deposit without requiring lenders’ mortgage insurance. This policy will involve the government (read taxpayers) guaranteeing 15% of vitually all first home buyer mortgages.

Add the expansion of federal and state government shared-equity schemes into the mix and you have the ingredients for increased buyer demand and home prices.

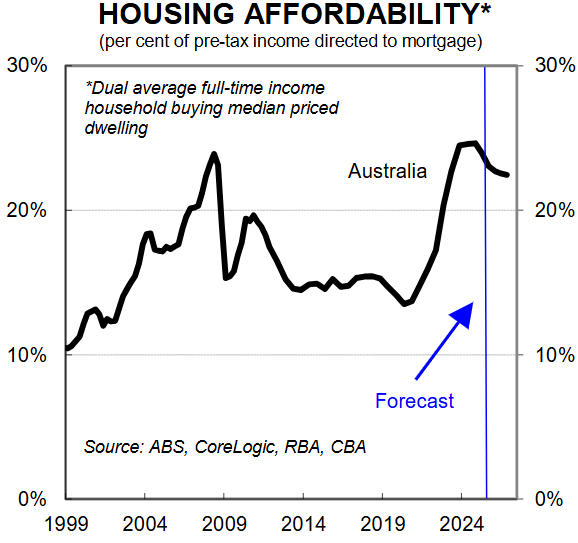

The following housing affordability chart from CBA highlights the key problem facing first home buyers in Australia.

Despite projecting further interest rate cuts and relatively modest national dwelling value growth of 6% in 2025 and 4% in 2026, CBA expects households to spend a historically high share of their incomes on mortgage payments for the median-priced home.

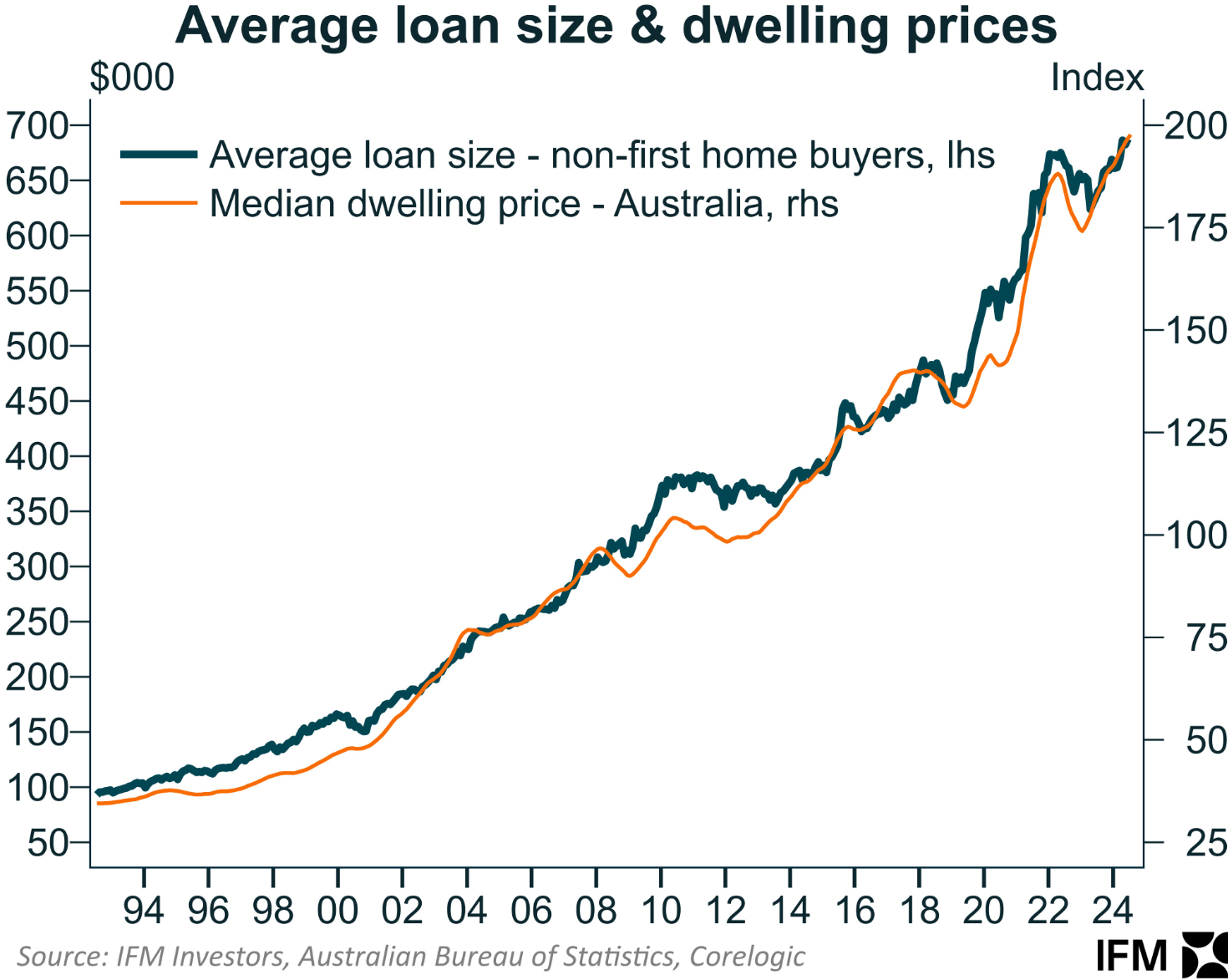

This outcome reflects the inalienable truth in Australia that lower mortgage rates and other demand-side policies tend to get capitalised into larger mortgages and higher home prices.

Expanding purchasing power, whether through lower interest rates, shared-equity and first-home buyer schemes, or other demand-side measures, does not improve structural housing affordability.

For housing affordability to actually improve, prices must fall relative to incomes.