Research by the McKell Institute warns that thousands of manufacturing jobs in Australia are at risk, particularly in regional areas

The report claims that China’s “aggressive” industrial subsidisation, now likely exceeding its defence spending, risks shuttering some 73,000 jobs in Australian regions reliant on refining and smelting metals.

“In the short-term, China’s geoeconomic strategy is designed to onshore as much global heavy industrial capacity as possible”, McKell Institute chief executive Ed Cavanough said.

“In the longer-term the strategic goal is limiting the viability of critical manufacturing in competitor economies, including Australia”.

“This would create a huge long-term economic advantage for China, and hobble Australia’s industrial capacity”, he said.

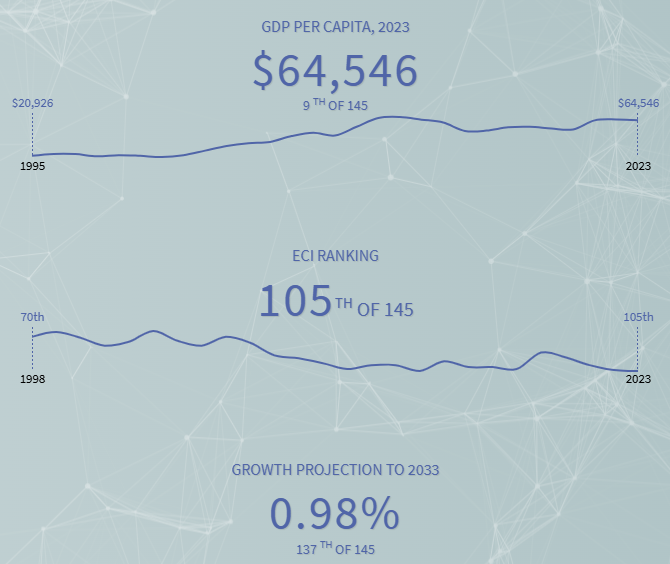

The McKell Institute’s warning comes amid the latest Harvard University index of economic complexity, which ranked Australia a lowly 105th out of 145 nations, down from 70th place in 1998. Australia’s economic complexity is now ranked behind Botswana.

“Compared to a decade prior, Australia’s economy has become less complex, worsening 6 positions in the ECI ranking”, Harvard noted.

“Australia is less complex than expected for its income level. As a result, its economy is projected to grow slowly”.

“The Growth Lab’s 2033 Growth Projections foresee growth in Australia of 1.0% annually over the coming decade, ranking in the bottom half of countries globally”, Harvard said.

Indeed, Australia’s 1.0% annual growth projection is ranked 137th out of 145, according to Harvard Growth Lab.

Australia’s economic complexity (Harvard Growth Lab)

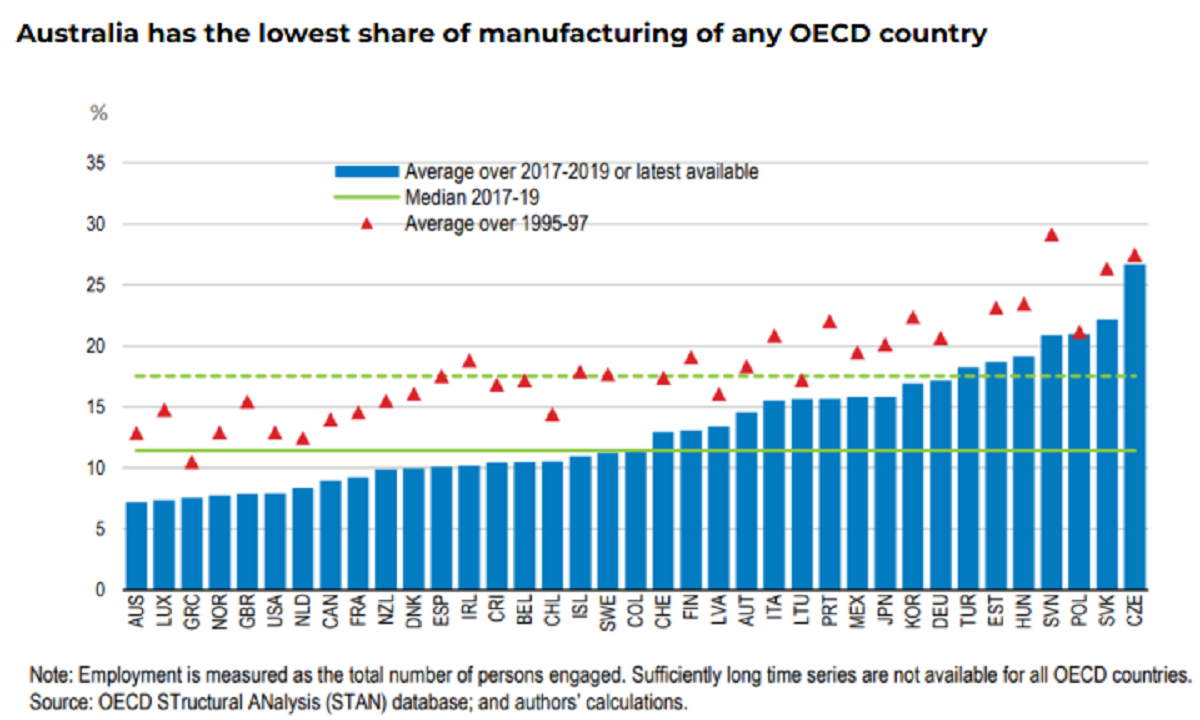

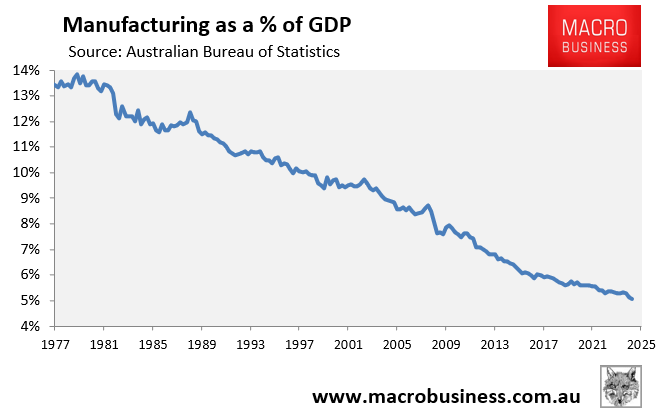

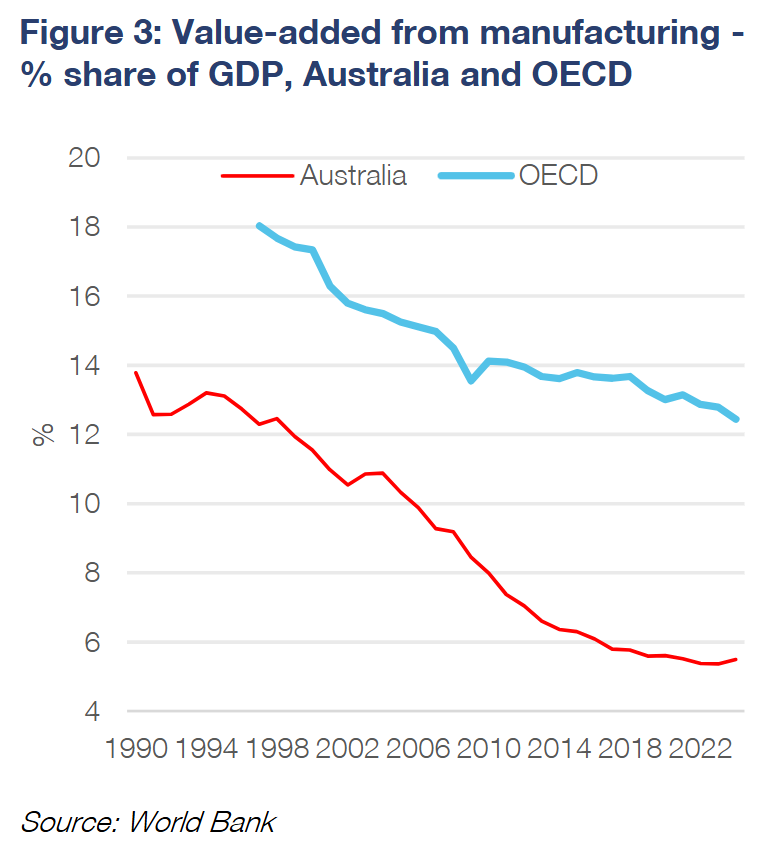

A major explanation for the decline in Australia’s economic complexity is the collapse of its manufacturing sector, which is now the smallest in the OECD as a share of the economy.

In Q1 2025, manufacturing’s percentage of GDP decreased to 5.1%, down from 8.9% two decades ago and 15% in the mid-1970s.

Therefore, the McKell Institute’s warning of a further contraction in manufacturing risks deindustrialising the economy further, lessening its diversity and complexity, and making Australia less self-sufficient.

University of Technology Sydney economist Roy Green argues that the government should step in and subsidise manufacturing facilities to process raw materials.

“This is a down payment on the future, and the future is not a world of free markets”, he told The ABC.

“The future is a world in which we have to develop sovereign capability in the production of these metals in order to participate on equal terms in global markets”.

“We, at the moment, have far too little invested in the value add of our unprocessed raw material exports, and a good case in point is lithium, where we produce 50% of the world’s production”.

“We export 90% to China and we capture only 0.53% of its value”, he said.

In February, the federal and SA governments announced a joint $2.4 billion bailout after the Whyalla steelworks owned by British industrialist Sanjeev Gupta collapsed into administration.

Last week, the Albanese government joined with the South Australian and Tasmanian governments to announce a $130 million bailout for Brussels-based global minerals and metals producer Nyrstar’s loss-making lead and zinc smelters in Port Pirie and Hobart.

SA Premier Peter Malinauskas says the rescue package for Nyrstar is not a bailout but an investment.

The Albanese government’s “Future Made in Australia” policy also aims to build sovereign manufacturing capabilities, including the production of critical minerals and processing of other “future-facing” metals required for the net-zero energy transition.

The cold hard reality is that Australia’s manufacturing sector has no future so long as energy—i.e., gas and electricity—continues to rise and cost and becomes less reliable.

As illustrated below by Vivek Dhar from CBA, “the decline in the share of manufacturing in Australia’s economy has been faster than advanced economies, reflecting the overall challenges of keeping labour, materials, and energy prices low enough for Australia’s manufacturing sector to remain competitive”.

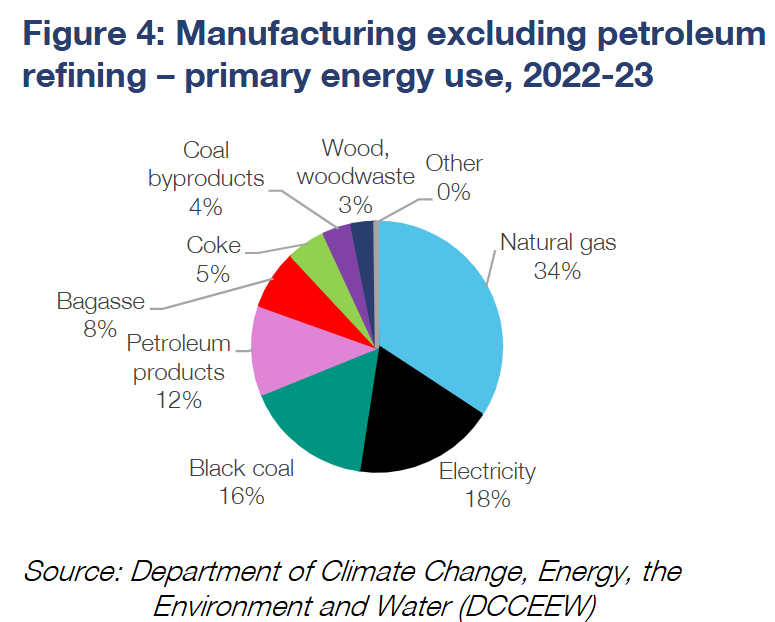

“Manufacturing, excluding the petroleum refining sector, primarily uses natural gas for its energy consumption”, noted Dhar. “Electricity is the second largest energy source, followed by black coal, petroleum products and then more fossil fuels”.

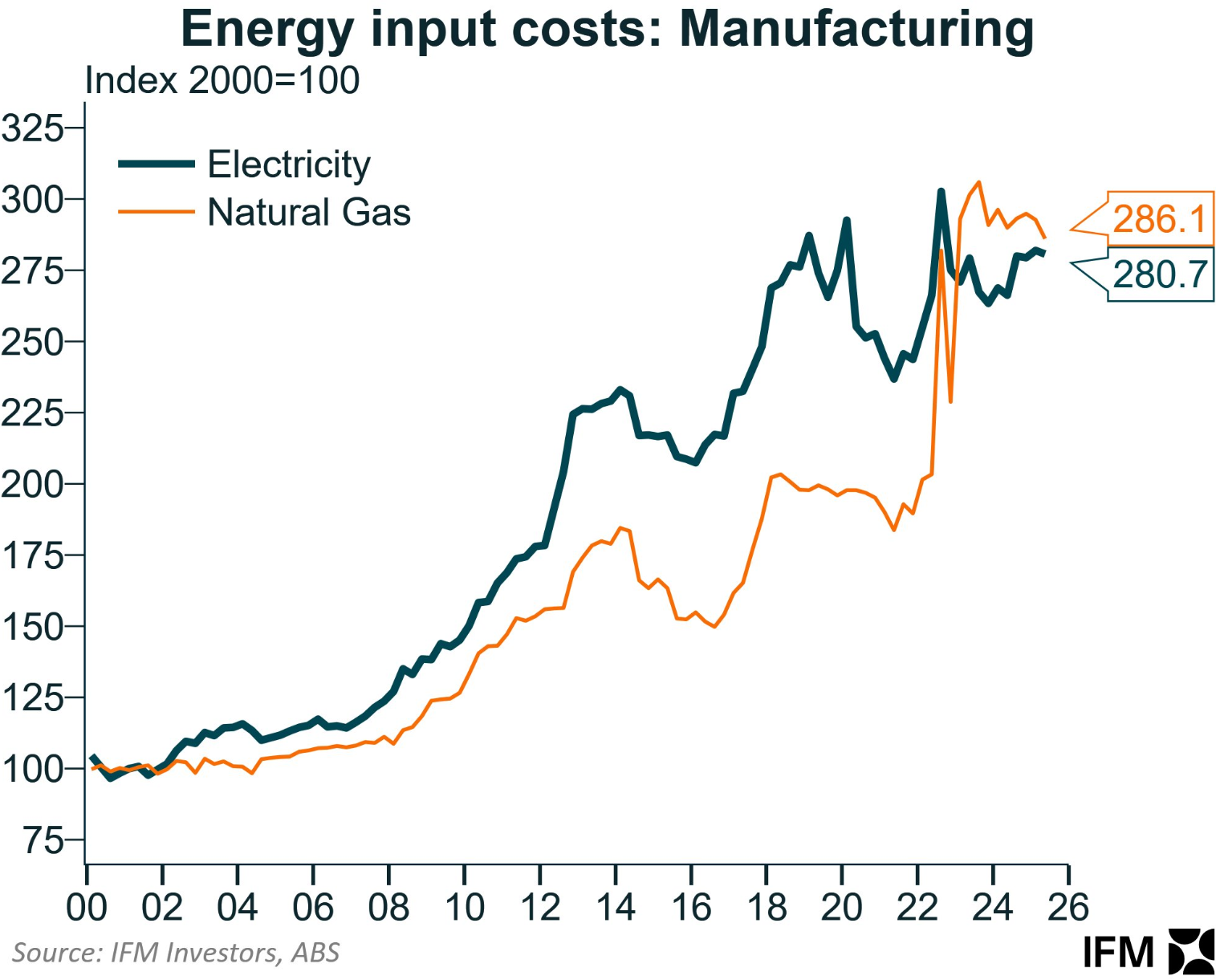

Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors, clearly illustrates the energy conundrum facing the manufacturing sector.

Natural gas input costs in manufacturing have increased by 186% since 2000, while electricity costs have increased by 181%.

The increase in natural gas prices has been particularly severe since 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Not surprisingly, ASIC insolvency statistics revealed that over 1400 manufacturers nationally have collapsed since 2022-23.

Among these, Incitec Pivot, a major fertiliser producer, closed its Australian facilities due to increased energy expenses.

Qenos, Australia’s last major plastics producer, closed in 2024 due to excessive energy costs, leaving the country completely reliant on polymers imported from China.

Oceania Glass, Australia’s sole architectural glass maker, closed in February 2025 after 169 years of operations due to rising energy prices and Chinese dumping.

Orica, the world’s largest manufacturer of mining explosives, chemicals, and agricultural fertilisers, and BlueScope Steel have threatened to close their Australian facilities and relocate to the United States in response to rising energy prices.

The reality is that without affordable and reliable gas and electricity, Australia’s manufacturing industry will continue to shrink, the country will deindustrialise, and it will become less diversified.

Unfortunately, energy prices in Australia will continue increasing.

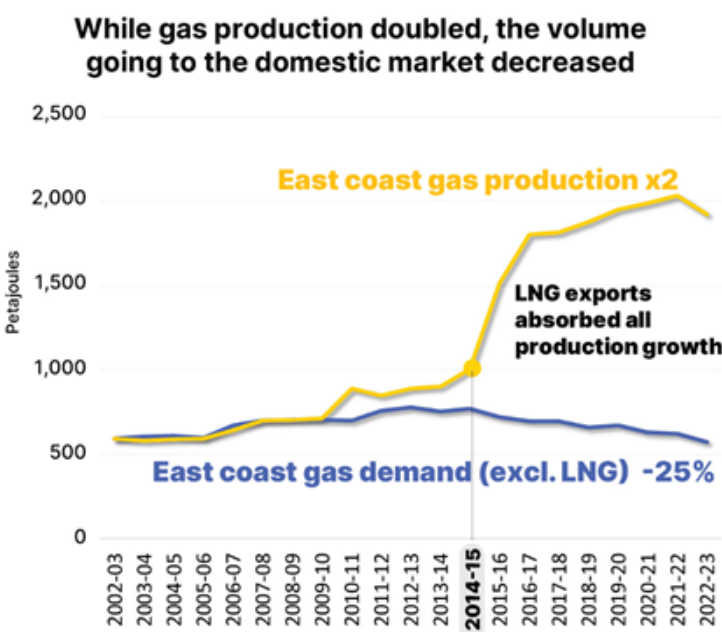

East Coast Australia’s failure to implement a domestic gas reservation scheme is a major driver of rising energy prices.

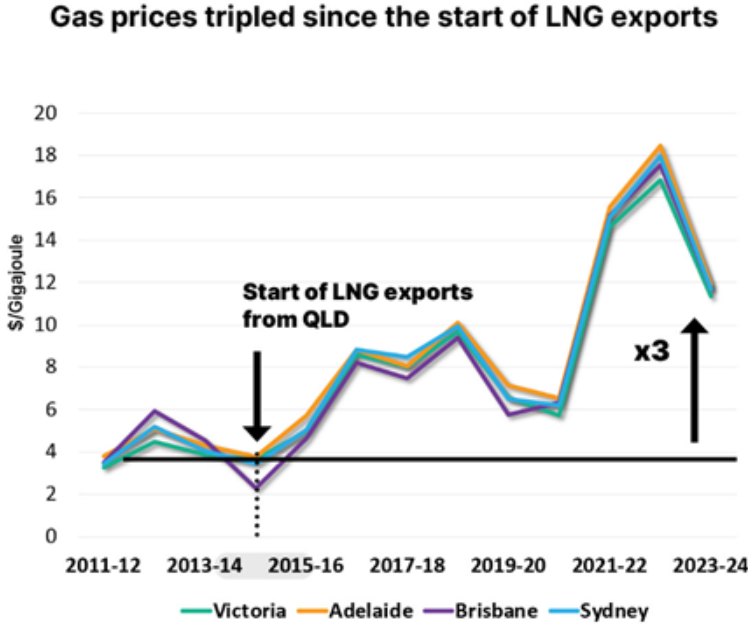

The East Coast began exporting natural gas from Gladstone in 2015. Since then, the East Coast has doubled its gas output while supplying 25% less gas to the domestic market.

As a result, an artificial gas shortage has formed, doubling East Coast gas prices to around $12 per gigajoule.

East Coast Australia now has the highest gas prices of any exporting jurisdiction in the world. These high gas prices have contributed to higher electricity prices, as gas is a major marginal price setter in the wholesale market.

The problem will only get worse if the East Coast begins importing gas into New South Wales, Victoria, and possibly South Australia to alleviate artificial domestic shortages.

Once liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports begin, East Coast gas prices will surge to import-parity levels of around $20 per gigajoule, raising electricity prices.

Implementing a domestic reserve on the East Coast is crucial for cutting prices and mitigating the negative effects of LNG imports.

Second, Australia’s dogged pursuit of ‘net zero’ and the closure of baseload coal facilities will raise electricity prices.

The development of a network of renewable energy generators, transmission, and storage will require hundreds of billions of dollars, which will eventually be reflected in increased power bills and taxes to cover subsidies.

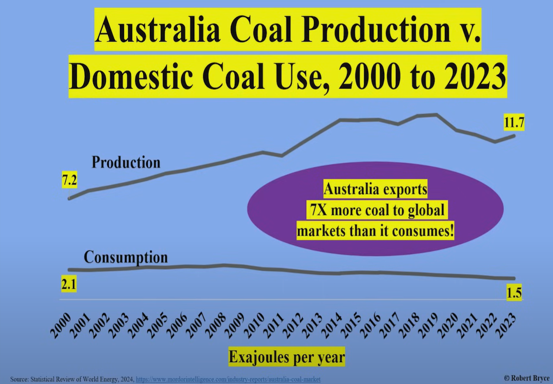

Australia leads the world in coal exports and is second in natural gas exports. We export around seven times more coal than we consume as a nation, as well as four times more gas.

Australia also boasts the world’s largest uranium reserves.

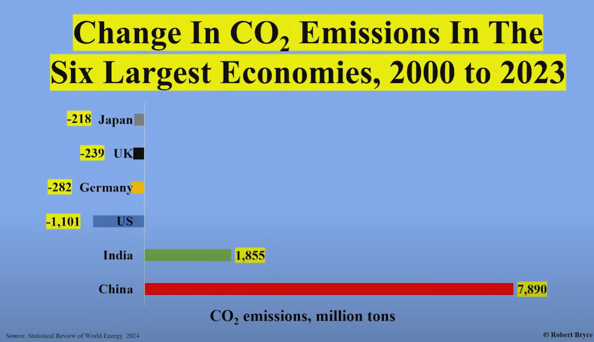

Australia should have some of the world’s cheapest gas and electricity, but it has opted to deny itself access to this energy while exporting energy security to Asia, notably China and India, which are driving the growth in global emissions.

While all Australians will bear the consequences of our energy policy failings, the energy-dependent manufacturing sector will suffer the most.

Australia will become an even greater industrial wasteland, with a less diverse and complex economy, poorer productivity, and ultimately lower living standards.