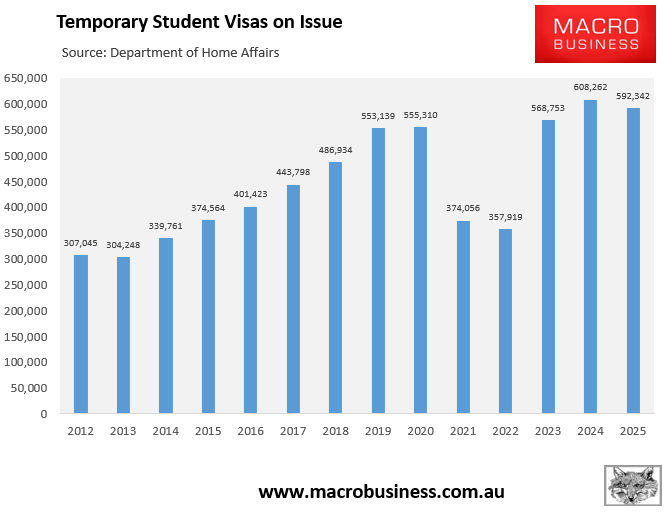

The latest temporary visa data for Q2 2025 from the Department of Home Affairs shows that the total number of student visas on issue in Australia fell marginally to 592,342, down from 608,262 a year prior.

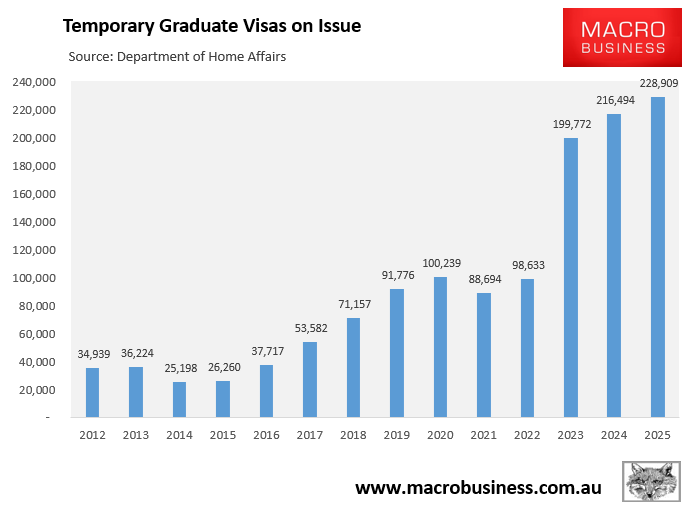

However, the slight fall in temporary student visas on issue was offset by the rise in graduate visas, which hit a record high of 228,909 in Q2 2025, up from 216,494 a year earlier.

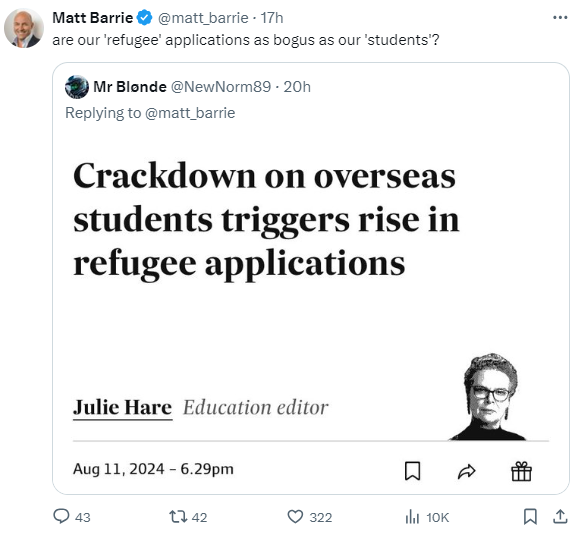

A year ago, Julie Hare from The AFR reported that the Albanese government’s ‘crackdown’ on bogus international students using private colleges for backdoor work visas had triggered a jump in bogus refugee applications.

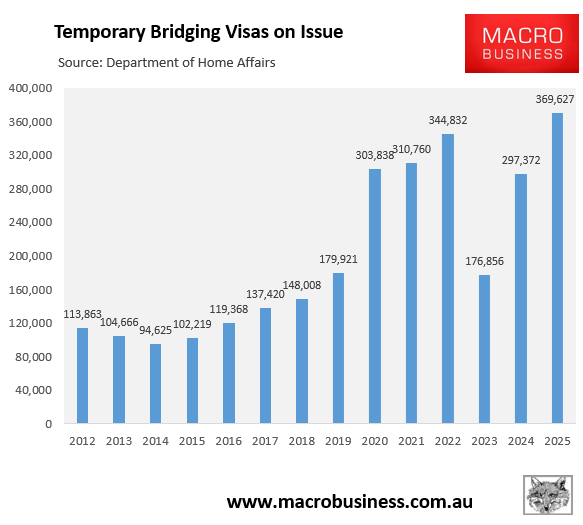

This rise in refugee applications is reflected in the number of bridging visas on issue, which jumped to a record high of 369,627 in Q2 2025, up from 297,372 a year earlier:

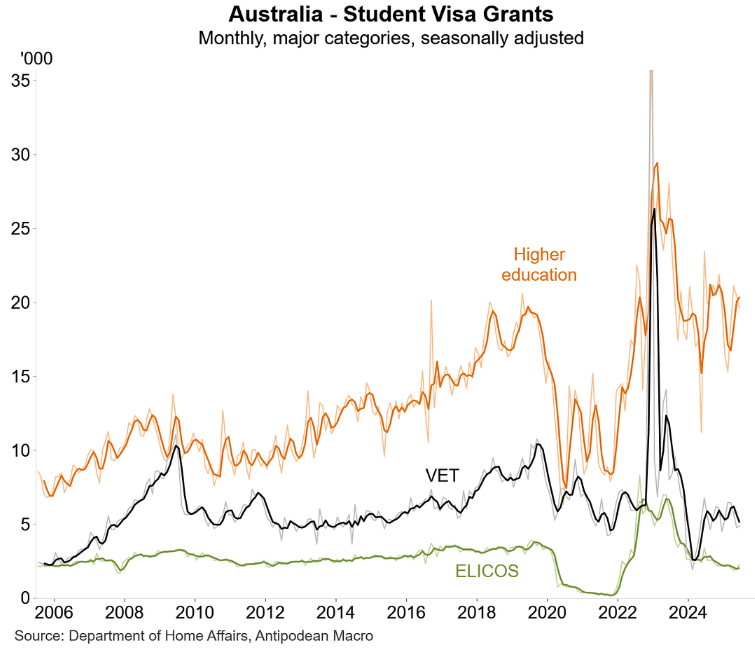

The Albanese government’s ‘crackdown’ on bogus student visas does, however, appear to be bearing some fruit, with the Department of Home Affairs showing a substantial reduction in grants for VET and ELICOS (i.e., English-language) courses.

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, visa grants to study at higher education institutions (i.e., universities) are around, or a bit above, pre-pandemic levels, whereas grants for VET and ELICOS are below pre-pandemic levels.

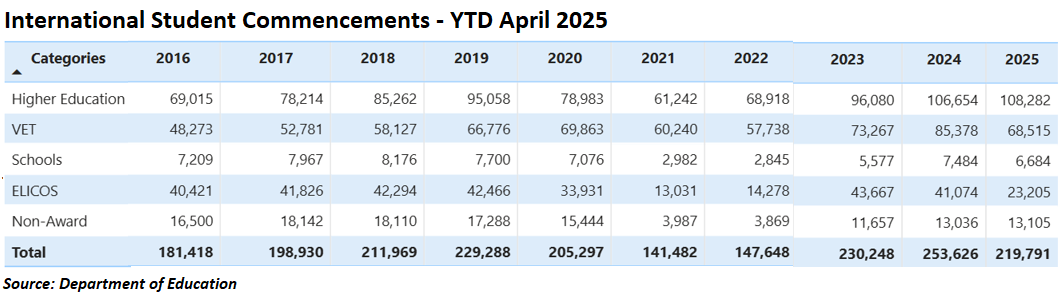

Separate Department of Education data to April also shows a sharp decline in commencements for VET and ELICOS over the past year.

Commencements for VET fell to 68,515 in the year to April 2025, down from 85,378 a year earlier. They are now tracking at around the pre-pandemic (2019 and 2020) level.

ELICOS commencements have fallen especially sharply, to 23,205 in the year to April 2025, down from 41,074 the year prior. ELICOS commencements are now tracking at their lowest level in a decade outside of the pandemic.

It appears, therefore, that the Albanese government’s international student crackdown has fallen on private colleges rather than universities.

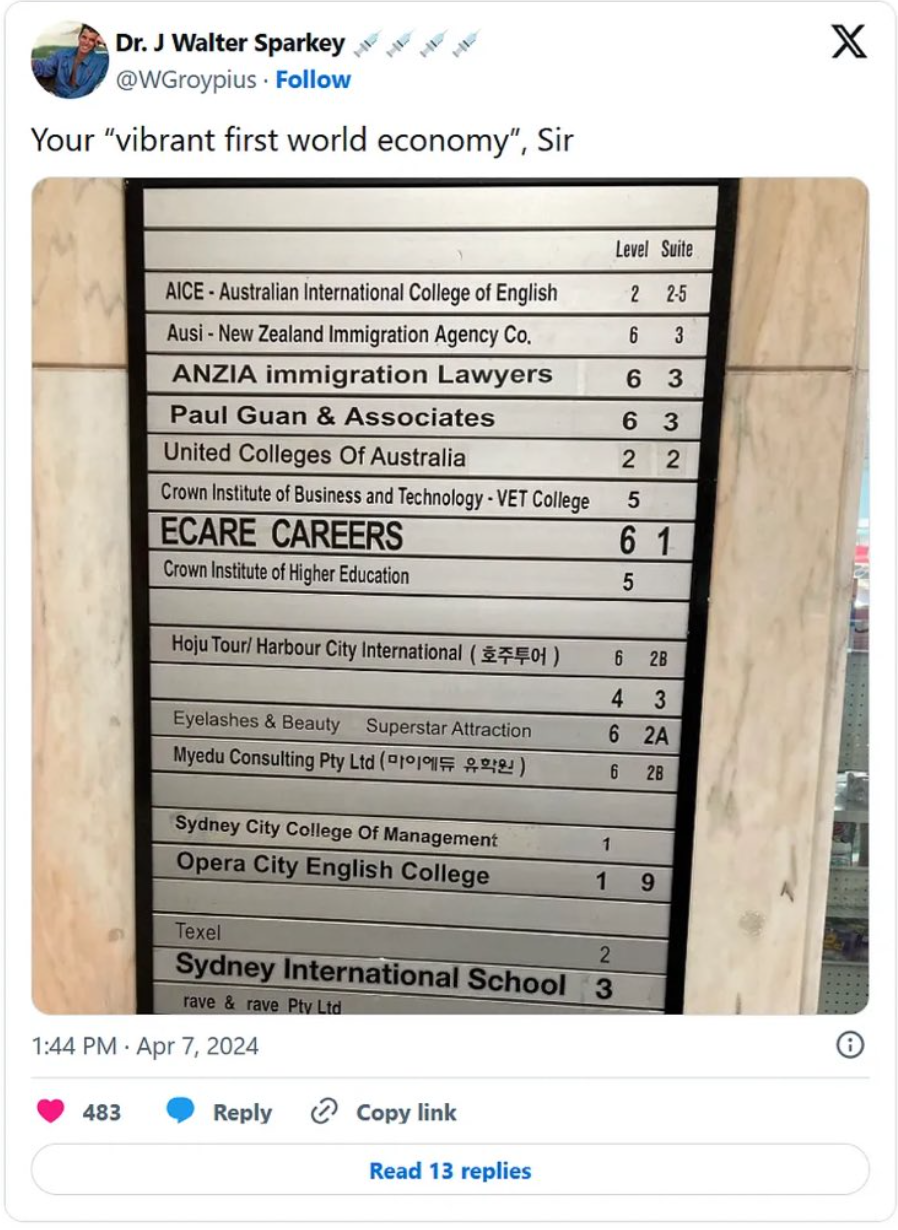

This is a good result, given there are around 3,800 registered training organisations in Australia, many of whom are spurious.

Indeed, the ABC’s Adele Ferguson recently labelled the $7 billion-a-year private college sector “shadowy”, chock-full of “dodgy operators, bogus qualifications and financial fraud”.

Ferguson claimed that “colleges and migration and education agents have spent decades exploiting the system” by “selling fake qualifications from a few hundred dollars to tens of thousands of dollars per student”.

The Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) told Ferguson that at the end of 2024, it was handling 174 serious matters, including allegations of cash-for-qualifications schemes, fraud, fake diplomas, and fabricated assessments.

These cases involved 138 training providers, 103 of whom cater to international students. The scale of misconduct was labelled “staggering”, with 68% of the serious matters involving fraud, “from visa scams and funding rorts to sham RPL processes that falsely legitimise unearned qualifications”.

“Some providers don’t deliver any actual training or assessment, while others run ghost colleges where students pay for a visa rather than an education”, the ABC reported.

Misuse of Australia’s student visa system has become so frequent that it is now considered a feature rather than a flaw.

Check out Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and former Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews enjoying a curry with an Indian billionaire operating a banned college.

The entire system of student visas and private colleges must be reset, with Mickey Mouse providers losing accreditation and visa applications being denied.

The federal government must also strengthen the immigration and Administrative Review Tribunal process to ensure that students return home when their visas expire or their applications for new visas are denied.

Australia’s visa system must aim for quality over quantity.