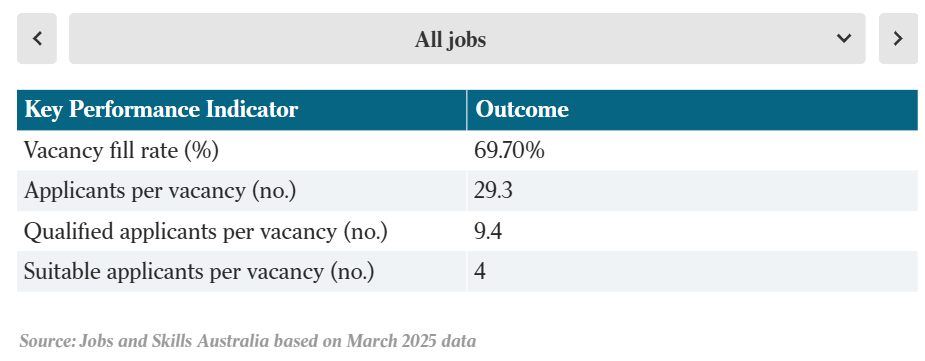

The Australian recently published Jobs and Skills Australia (JSA) data showing that there is an abundance of applicants per job. This suggested that concerns surrounding labour shortages are overblown.

At the aggregate economy level, there were 29.3 applications per vacancy, 9.4 qualified applicants per vacancy and 4 suitable applicants per vacancy:

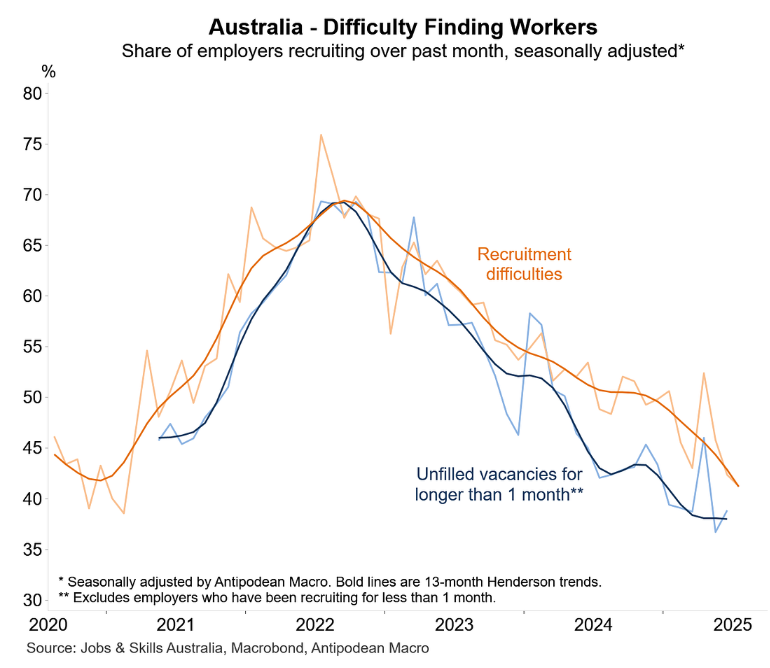

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, the latest data on recruitment difficulties from JSA corroborates this view.

Overall recruitment difficulty faced by Australian employers has fallen to pre-pandemic levels, according to JSA. The number of vacancies unfilled for longer than a month has also collapsed:

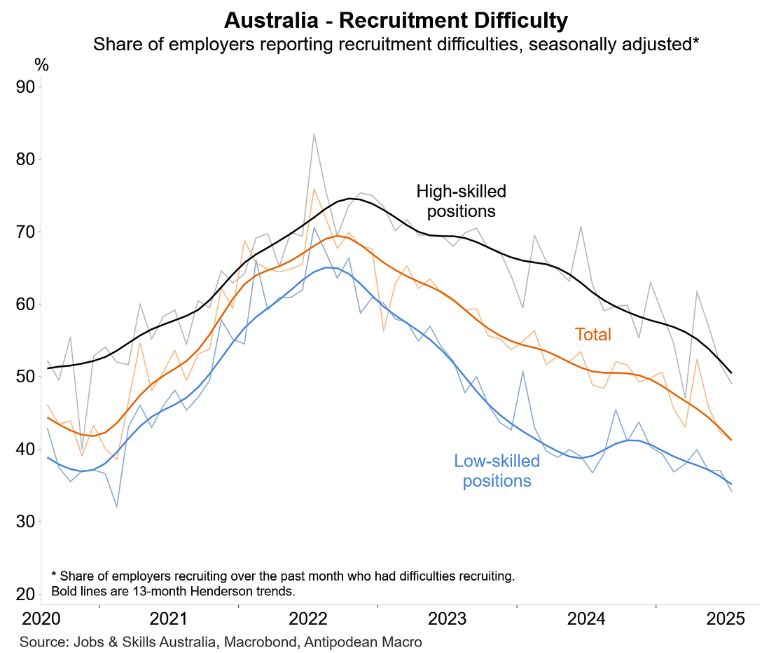

Australia is especially well-supplied with lower-skilled workers, whereas higher-skilled workers are in shorter supply.

Nevertheless, recruitment difficulties for both lower- and higher-skilled workers have retraced to pre-pandemic levels.

Therefore, at the aggregate level at least, labour shortages in Australia have evaporated.

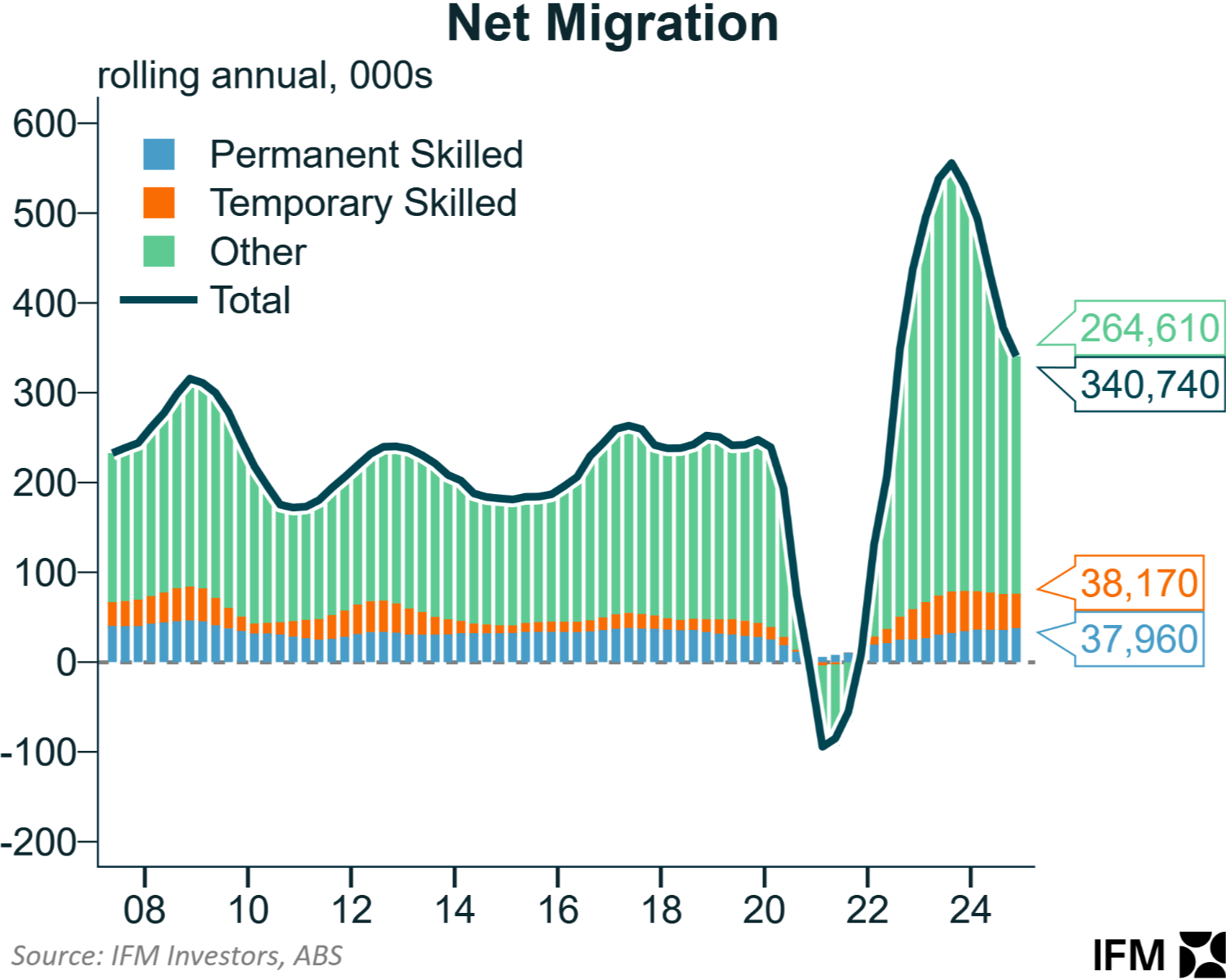

As noted yesterday, Australia’s migration system is flooding the nation with low-skilled workers.

The following chart from Alex Joiner, chief economist from IFM Investors, shows that the overwhelming majority of net overseas migration has been unskilled:

The Albanese government this month announced that it has raised the planning level for international students by 25,000 to 295,000 for 2026.

Labor also watered down the visa system by watering down English-language requirements.

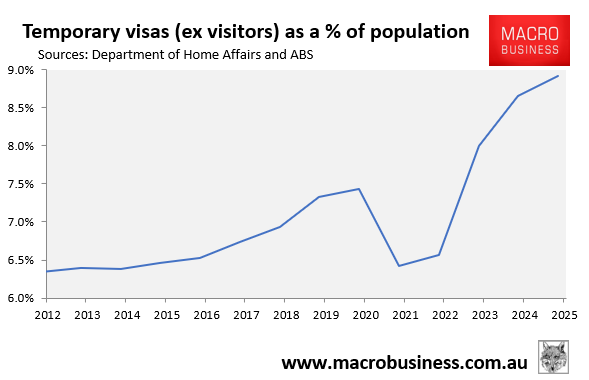

As a result, Australia’s international student and temporary visa numbers—which are already the highest in the advanced world relative to our population—will inevitably increase.

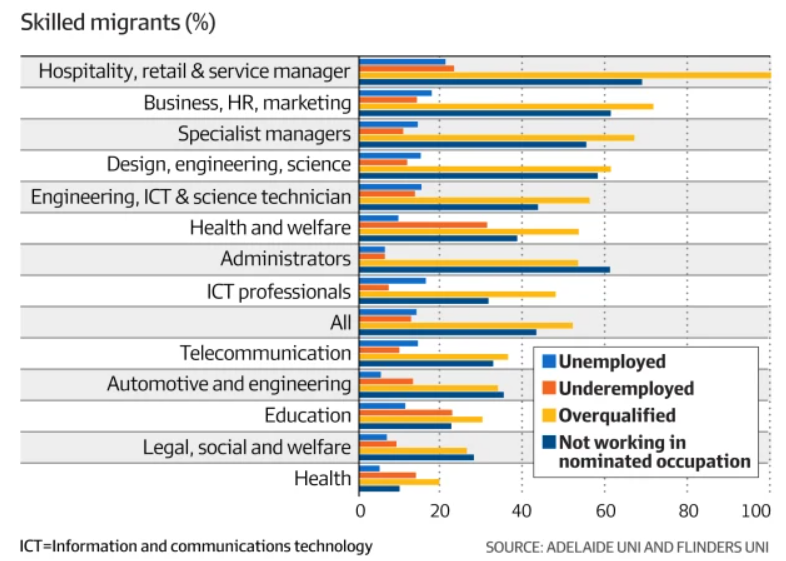

To add further insult to injury, Australia’s so-called ‘skilled’ visas aren’t actually very skilled.

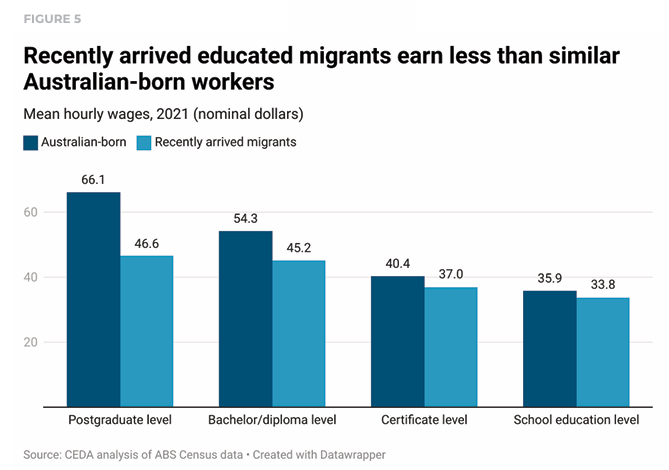

CEDA’s recent examination of census data revealed that Australia’s ‘skilled’ migrants are consistently underemployed, underpaid, and working in lower-skilled jobs. As a result, they are lowering Australia’s productivity growth.

“Many still work in jobs beneath their skill level, despite often having been selected precisely for the experience and knowledge they bring”, CEDA reported.

“Labour productivity and wages are closely linked, indicating that migrant labour is not being used as productively as it could be”.

“This decade, migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”.

Indeed, in 2023, Engineers Australia estimated that 100,000 qualified, skilled engineers in Australia were driving Ubers or doing other work that is not related to engineering.

George Tan from Adelaide University estimated that 43% of skilled migrants who entered via the state-sponsored visa system were not working in the occupation they claimed.

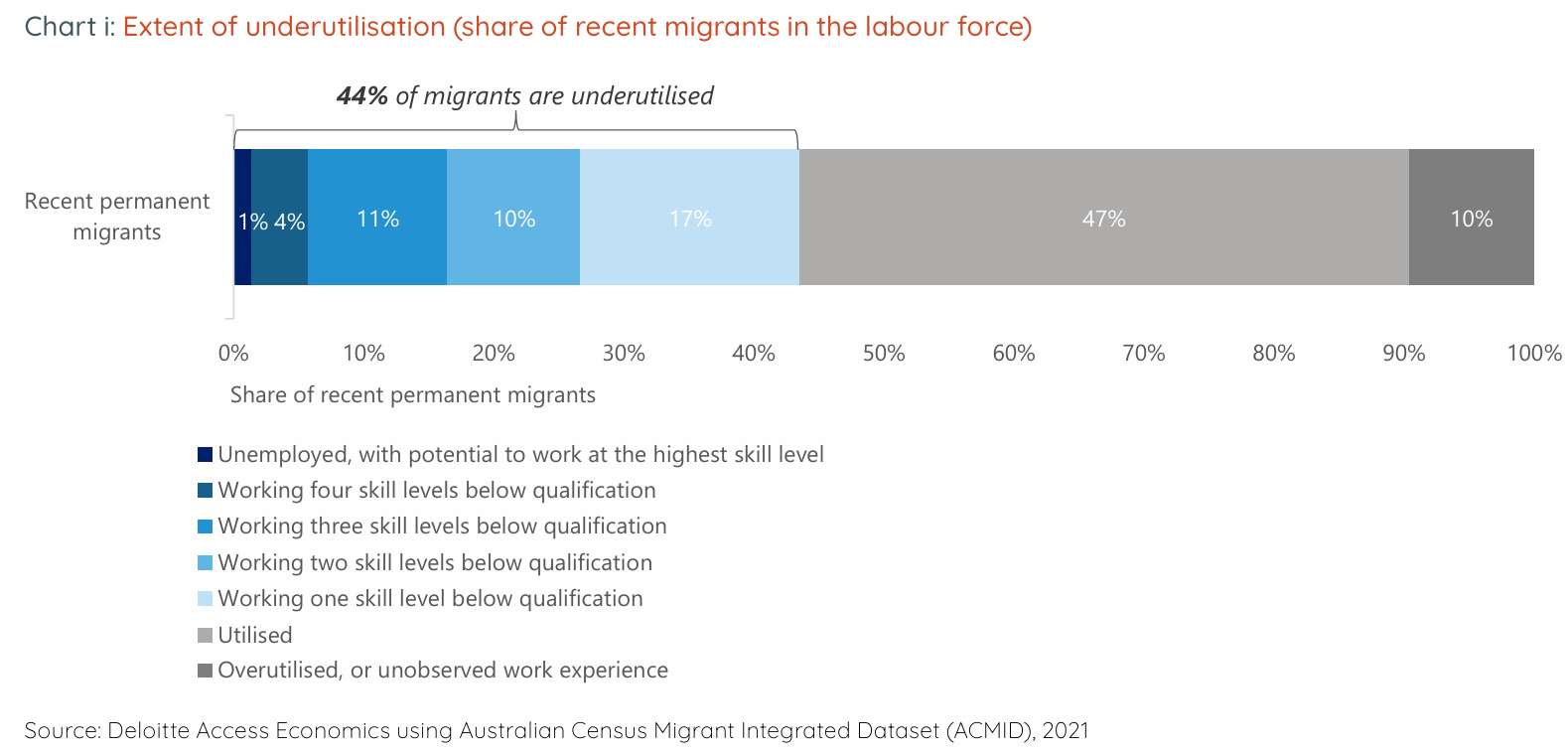

Likewise, Deloitte found that 44% (621,000) of permanent migrants in Australia worked in jobs below their skill level in 2023. The majority of these underemployed migrants came through the skilled stream.

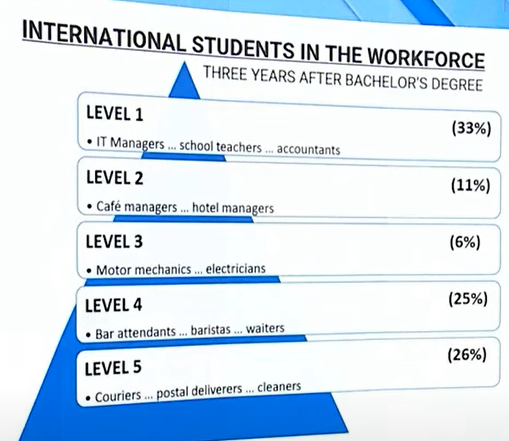

Finally, the 2023 Migration Review found that 51% of foreign-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees worked in unskilled employment three years after graduation.

Source: Migration Review, 2023.

Clearly, mass untargeted immigration has failed to provide Australia with the necessary skills, worsening infrastructure and housing shortages, as well as environmental deterioration.

Australia’s productivity has also been degraded by ‘capital shallowing’, since business, infrastructure, and housing investment has failed to keep pace with population growth, and the amount of capital investment per person has shrunk.

The obvious solution is to operate a significantly smaller and higher-skilled migration system.

Sadly, the Albanese government has taken the opposite approach, lifting the intake of international students by 25,000 and watering down English-language proficiency rules.