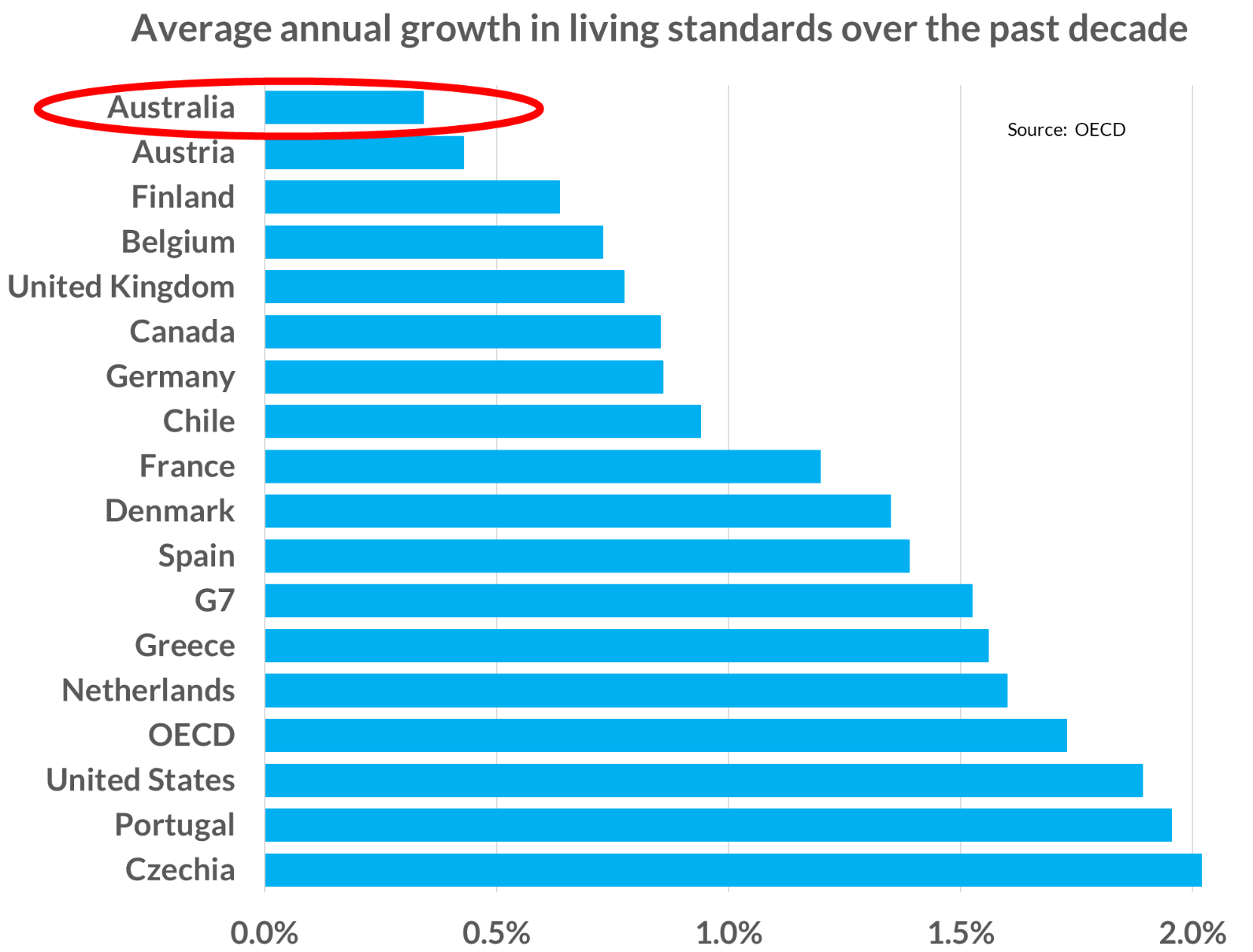

Independent economist Chris Richardson published the following chart on Twitter (X) showing that Australia has experienced one of the poorest increases in living standards over the past decade among advanced OECD nations.

“The good news is that Australia’s average has improved since my last update”, Richardson wrote. “The bad news is we still have a big challenge ahead”.

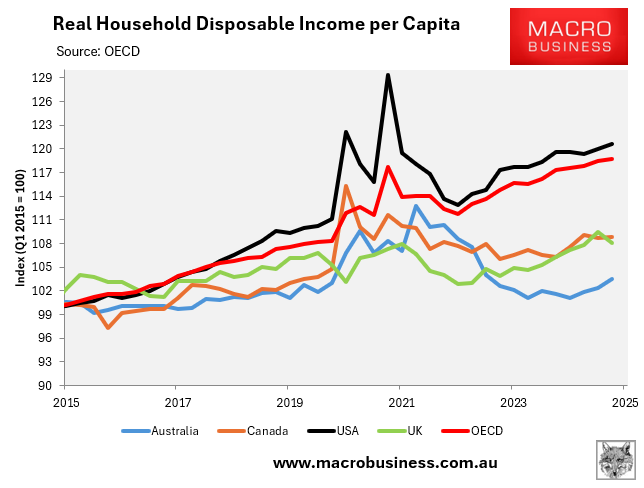

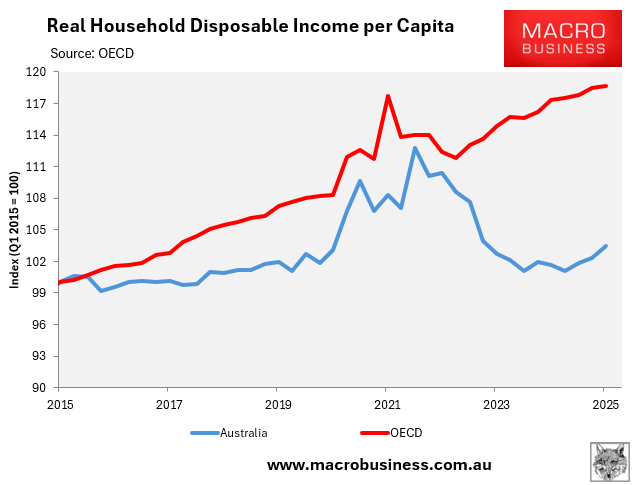

The chart inspired me to conduct an analysis of the growth in real per capita household disposable income—arguably the single best measure of per capita living standards—against other English-speaking OECD nations.

As illustrated below, Australia’s real per capita household disposable income grew by only 3.5% in the decade to Q1 2025. Australia’s growth was well below the other English-speaking nations in the OECD’s sample, namely Canada (8.9%), the USA (20.6%), and the UK (8.0%).

Australia’s 3.5% growth in real per capita household disposable income was also significantly below the OECD average of 18.7% over the decade.

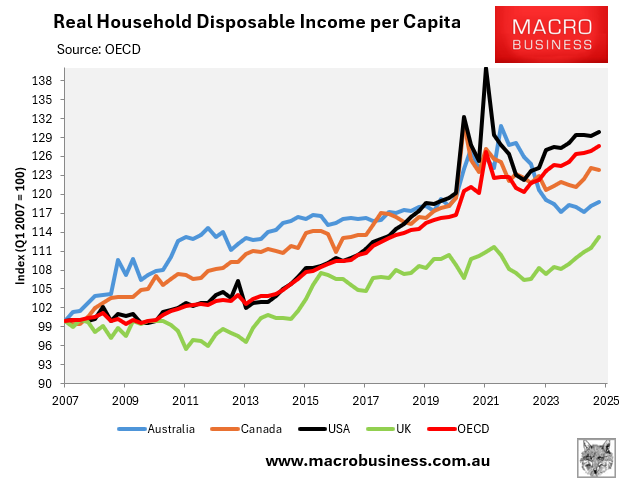

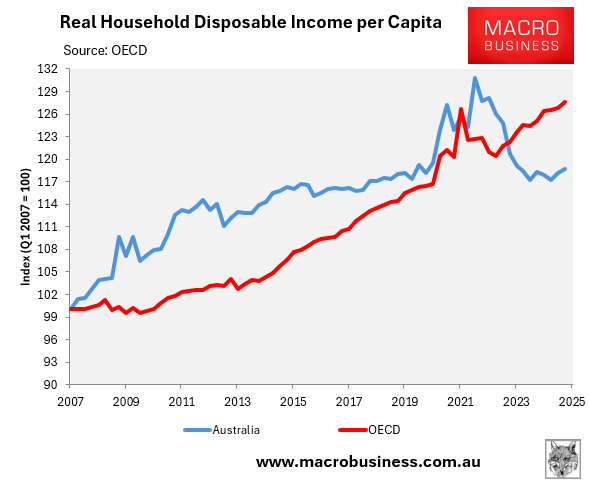

The news is somewhat better for Australians when we examine the growth in real per capita household disposable income since the inception of the OECD series in Q1 2007, just prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Australia’s 20% growth in real per capita household disposable income is better than the UK’s (12%), but worse than Canada’s (24%) and the US’ (31%).

Australia’s 20% increase in real per capita household disposable income since Q1 2007 also lagged well behind the OECD average of 28%.

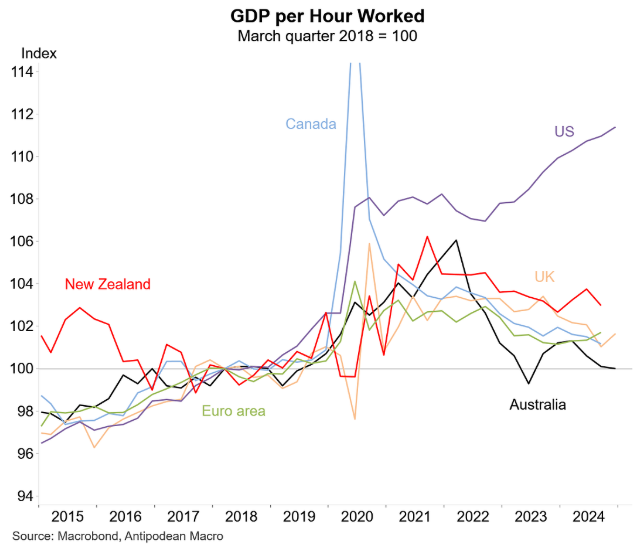

The decline in Australia’s living standards largely reflects the nation’s poor productivity performance, which ranks among the poorest in the OECD.

It is difficult to see how Australia’s position will improve in the period ahead.

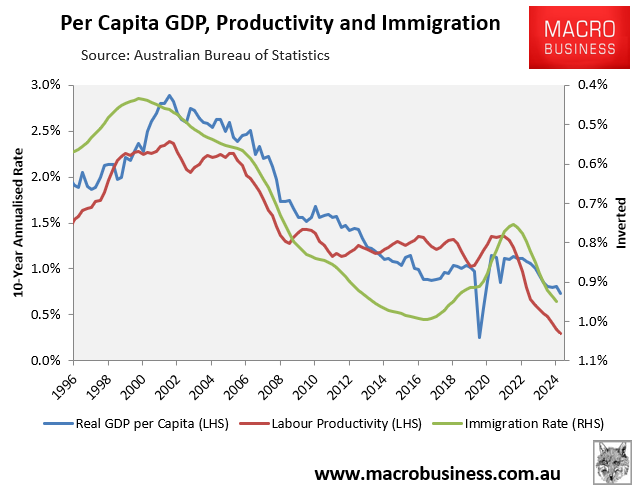

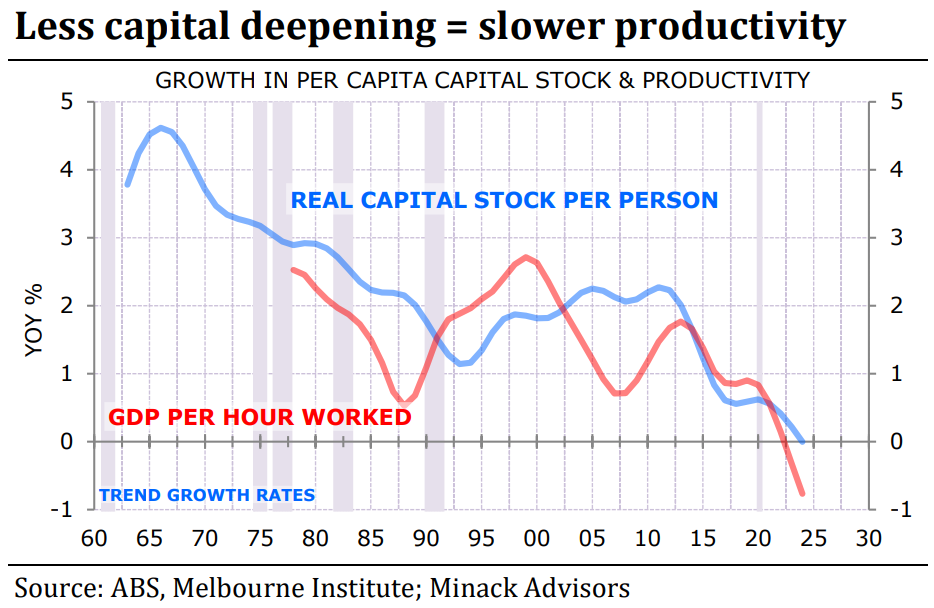

Australia’s productivity growth has been in decline for the past 20 years, driven lower by excessive low-skilled immigration, which has diluted the nation’s skills base and caused ‘capital shallowing’ as net private business investment, infrastructure, and housing has failed to keep pace.

As a result, the amount of capital investment per person has shrunk and everybody’s standard of living has gone down, not up.

Australia has also diluted its enormous mineral endowment and exports (which we don’t tax properly) among more people, making us worse off per capita.

Unfortunately, the Albanese government has doubled down on low-skilled migration by lifting the intake of international students by 25,000 and watering down English-language proficiency rules.

Australia is also committing energy policy suicide, which is forcing deindustrialisation and harming the nation’s productivity and growth potential.

The reality is that if you ration energy and force generation through less energy-dense sources like wind and solar, you ration productivity and growth.

The enormous costs of transmission and storage, and the intermittent nature of weather-dependent renewables, will ensure that Australia’s energy costs continue to rise, resulting in higher bills, inflation, and further manufacturing industry closures.

Australia’s failure to reserve adequate gas for domestic use adds to the problem, as gas is key to industrial processes and for electricity generation (firming). Higher gas prices mean more manufacturing closures and higher wholesale electricity prices.

So long as we continue down the road to a heavily renewable future, energy costs will rise and productivity and living standards will decline.