Australians aren’t as rich as they think

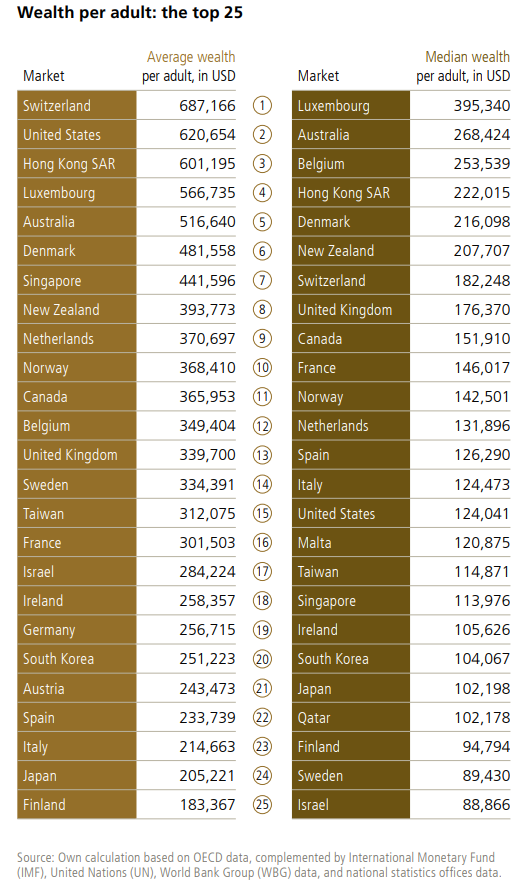

The 2025 UBS Global Wealth Report was released this week, which once again showed that the median Australian is among the wealthiest in the world.

UBS ranked Australians second in the world for median wealth, with the typical Australian worth US$268,424.

Australia also had 1,904 US dollar millionaires, according to UBS.

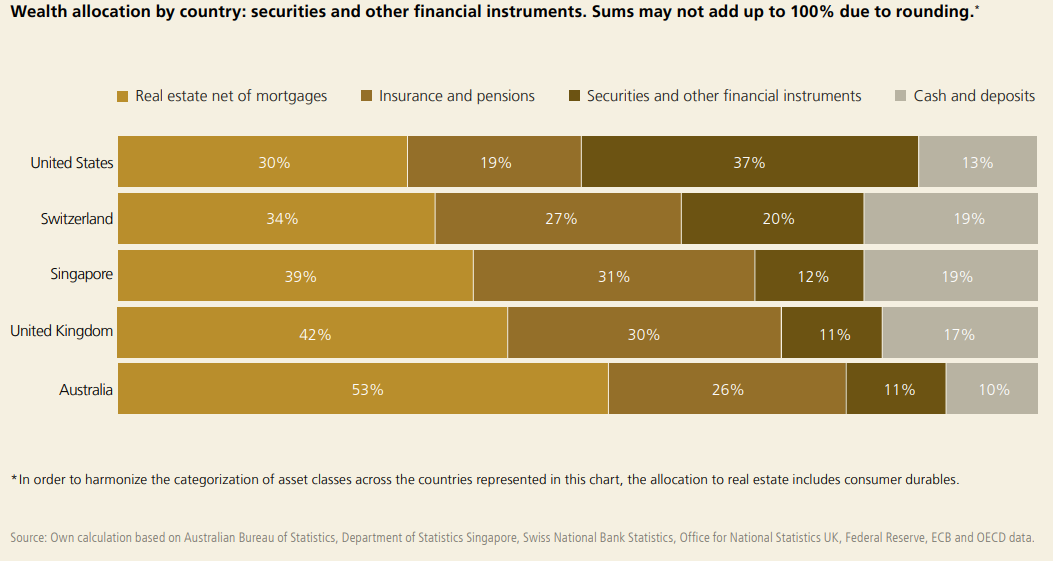

Not surprisingly, Australia is unique in that more than half of its household wealth is stored in illiquid residential property.

“Australia stands out for its real estate that makes up almost 53% of the country’s personal wealth, ahead of the United Kingdom and far ahead of the other markets”, UBS noted.

“In the United States, the proportion is 30%”.

“The proportion of wealth held in cash and deposits is the lowest in Australia at just above 10%, only half as much as in Switzerland, Singapore and the UK”.

Indeed, Australians are “wealthy” because we have some of the most expensive housing in the world.

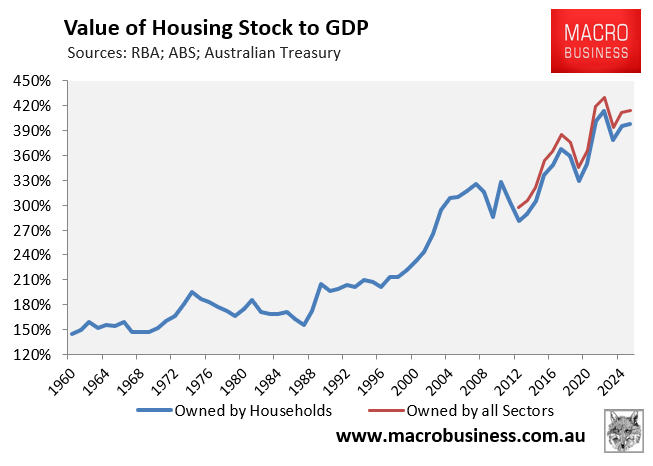

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australia’s housing stock was valued at $11,366 billion as of Q1 2025, equating to $1,002,500 per dwelling.

In Q1 2025, Australia’s housing stock was worth $396,400 per person in real terms, and it had more than tripled over 30 years:

Australia’s housing stock exceeded the size of the Australian economy by 4.14 times in Q1 2025.

By comparison, the United States’ housing market was only valued at only 1.6 times GDP.

Higher home values serve no benefit to owner-occupier households, who merely need somewhere to live.

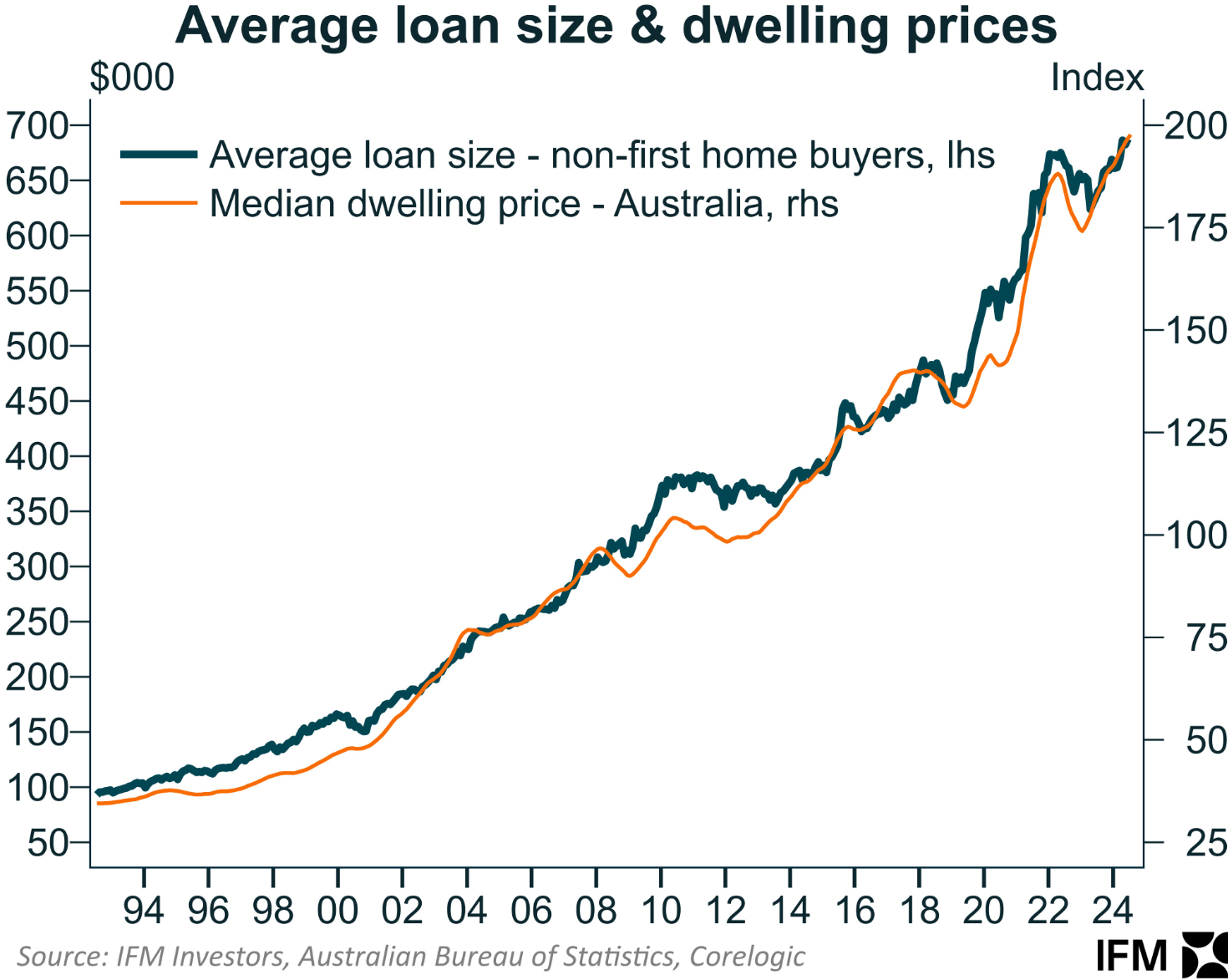

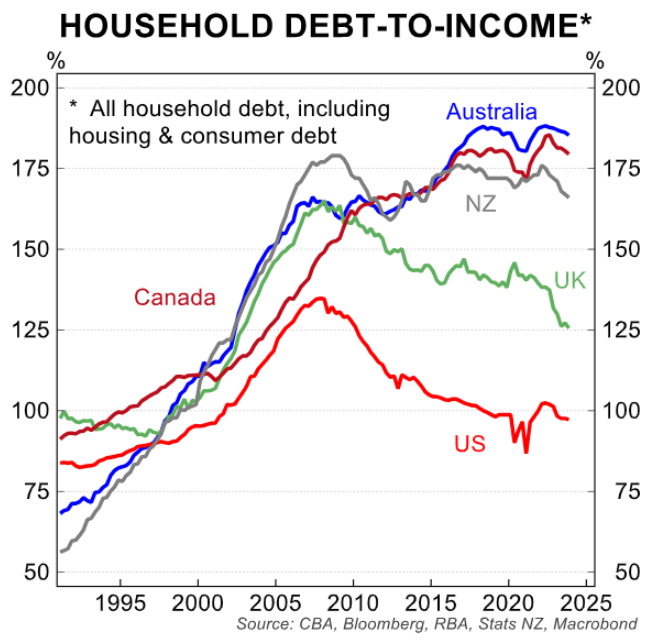

Meanwhile, Australians are suffocating in debt, accumulating ever-larger mortgages to offset the escalating costs of property.

As a result, Australian households hold some of the world’s largest debt levels.

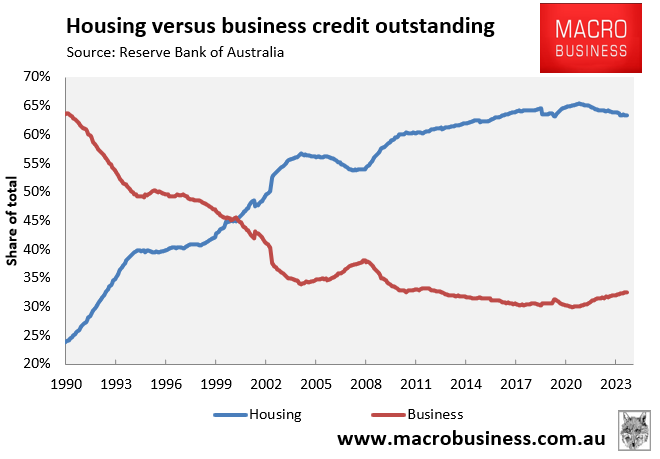

Australia’s banks have also expanded into massive building societies that prioritise residential housing loans above productive enterprises.

In 1990, businesses comprised around two-thirds of all bank loans, with mortgages accounting for only about one-quarter.

Thirty-five years later, the ratio has flipped, with more than two-thirds of bank loans for housing and barely one-third for business.

Australia would be wealthier with lower home prices:

If Australians are so wealthy, then why are so many people struggling financially?

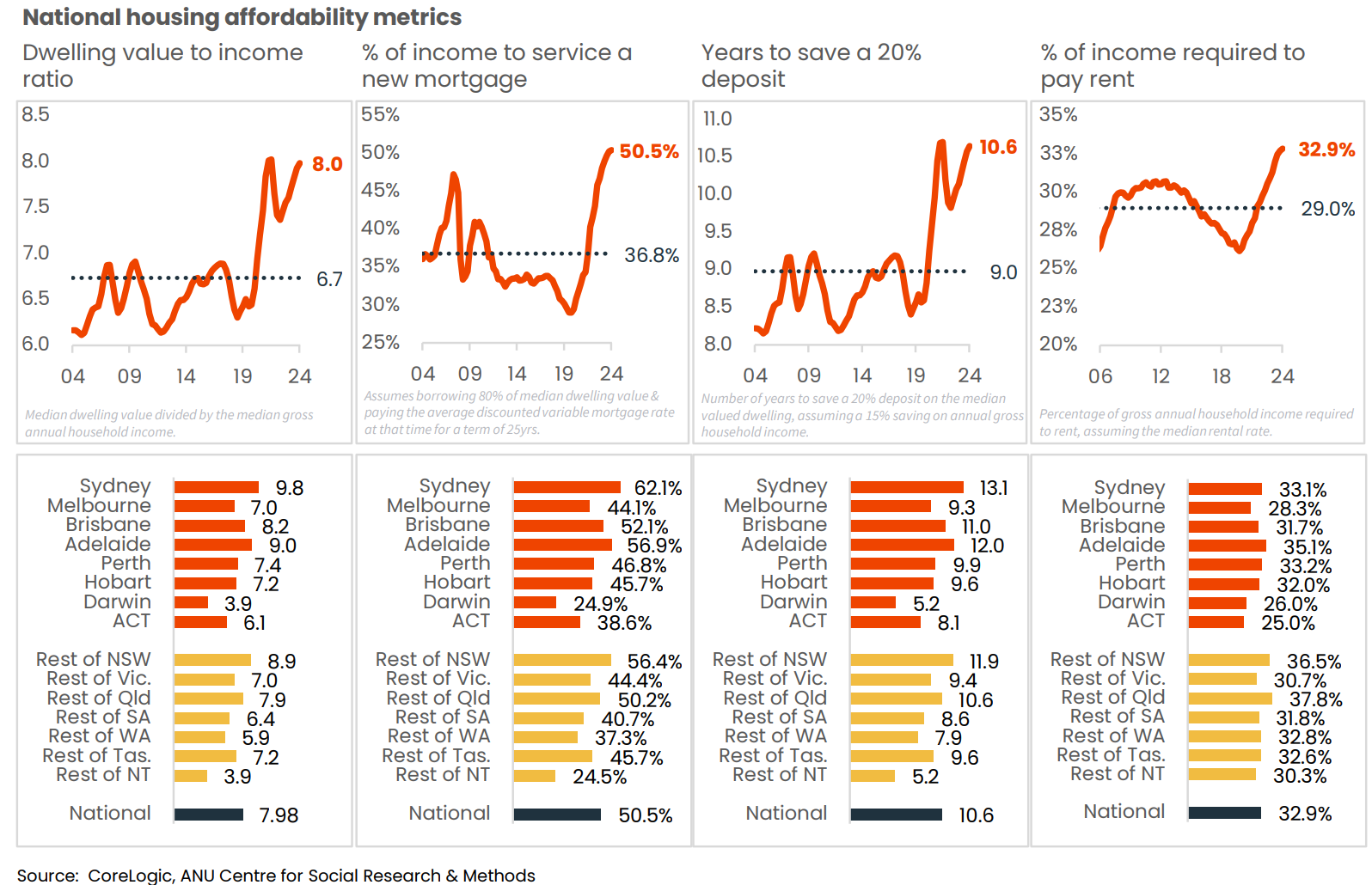

Many households are struggling under the weight of mortgage and rent payments, which, according to Cotality, are absorbing an unprecedented percentage of income.

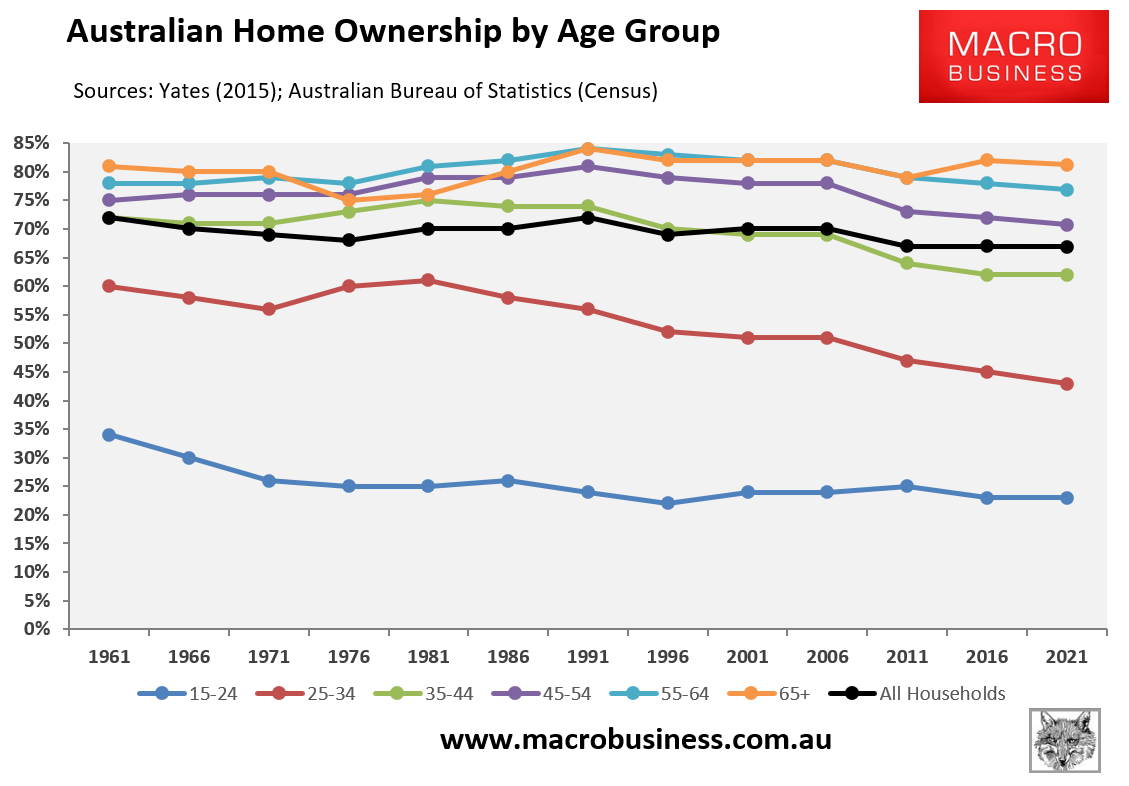

Given that housing affordability is at an all-time low and our younger generations are unable to buy a home without parental financial assistance, how can Australian households be considered the world’s second-wealthiest?

Australians would be wealthier if the average property were valued at $500,000 instead of $1 million, and household debt were 90% of income rather than 180%.

Australia would be a considerably more egalitarian society, and its residents would be financially better off if homes cost half as much as they do now, with half the debt.

According to the 1991 Census, Australia’s homeownership rate was approximately 5% greater than it is today. Homes cost about three times income (compared to eight times today), and household debt was 70% of income, compared to 180% today.

Banks also lent roughly two-thirds to businesses and one-quarter to mortgages.

Despite having substantially less property wealth, Australian households fared far better in 1991 than they do today. The Australian economy was also significantly more balanced and diverse in 1991 than it is today.

Australia’s high housing costs have a profoundly negative impact on younger and future generations, who must pay far more for accommodation than they would otherwise.

A home, whether it costs $500,000 or $2 million, serves the same purpose: to provide shelter. For most people, increasing housing “wealth” is irrelevant.

Ultimately, Australia’s bloated $11.3 trillion housing market represents a significant misallocation of capital that has harmed productivity, equity, and the broader economy.

Australia’s economy would be more balanced and productive if capital were focused towards fostering innovation and capital deepening rather than increasing house prices.