Australian manufacturing is dying and nobody cares

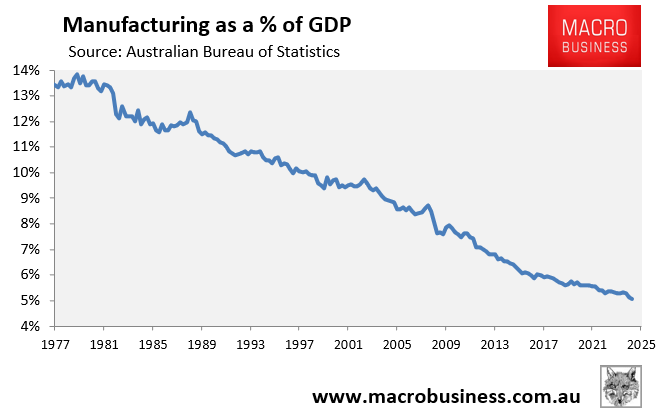

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) national accounts showed that Australia’s manufacturing sector comprised a record low share of GDP.

In Q1 2025, manufacturing’s percentage of GDP decreased to 5.1%, down from 8.9% two decades ago and 15% in the mid-1970s.

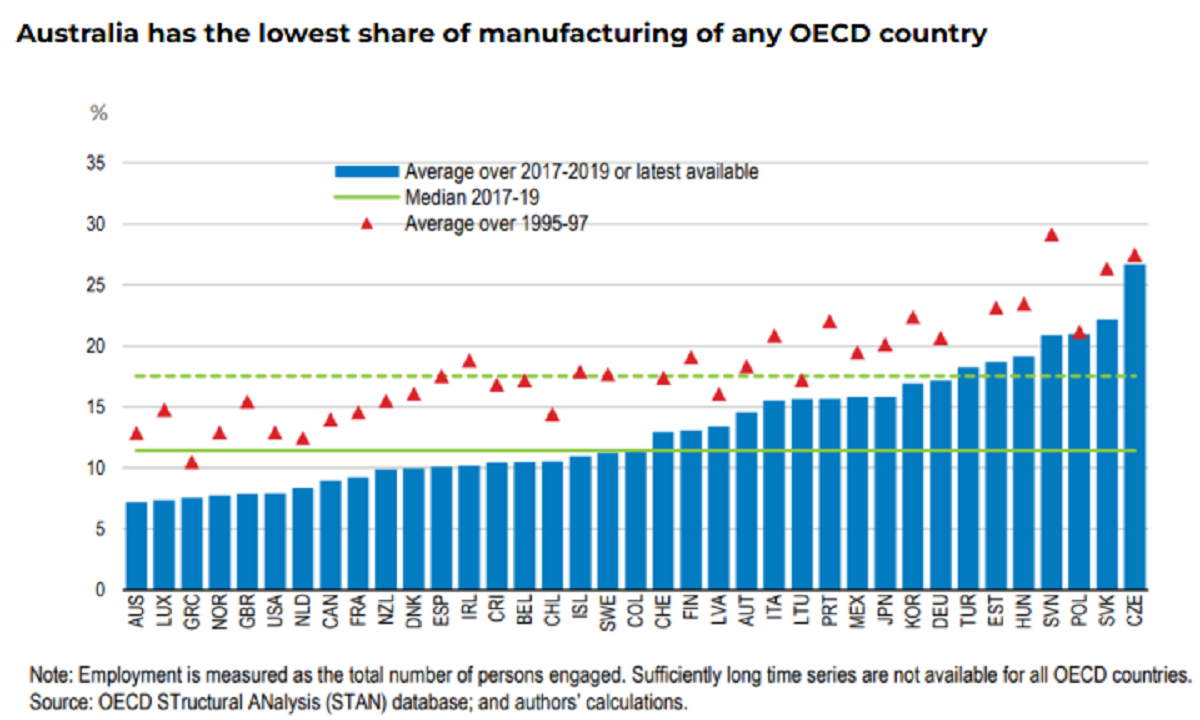

Australia has the smallest manufacturing share in the OECD, making it one of the least self-sufficient industrialised economies.

There are several factors contributing to Australia’s structural loss in manufacturing.

Tariff cuts in the 1980s and 1990s reduced Australian manufacturing’s competitiveness versus imports, shrinking the sector.

During the 2000s commodity boom, the Australian dollar rose in relation to other currencies, making the local manufacturing sector even less competitive versus imported goods and export markets.

Finally and most importantly, rising energy prices—both electricity and gas—have driven up operating costs, making Australian manufacturing less competitive.

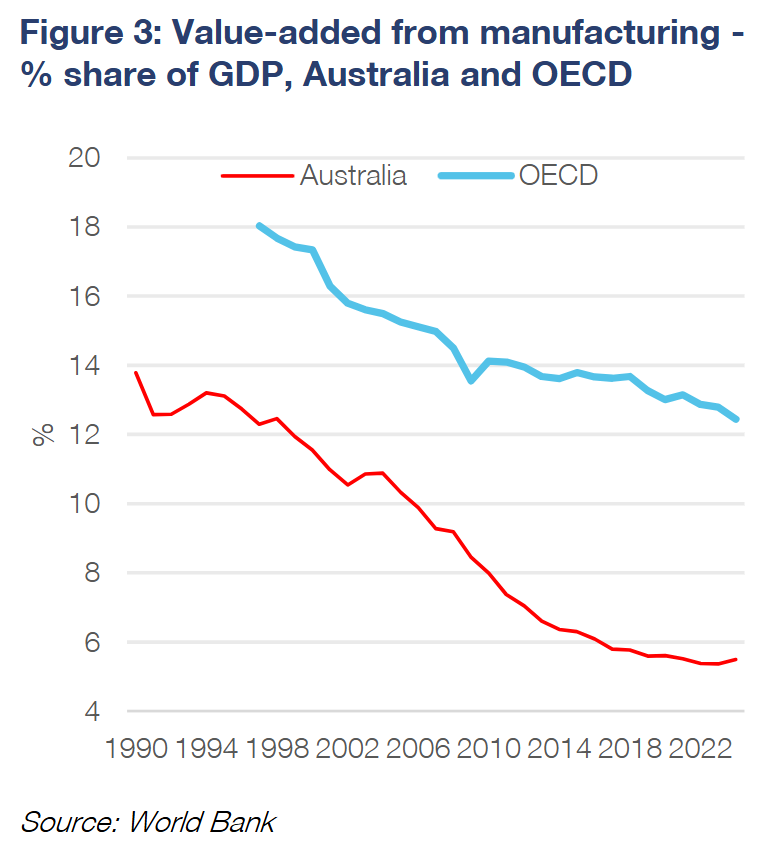

As illustrated below by Vivek Dhar from CBA, “the decline in the share of manufacturing in Australia’s economy has been faster than advanced economies, reflecting the overall challenges of keeping labour, materials, and energy prices low enough for Australia’s manufacturing sector to remain competitive”.

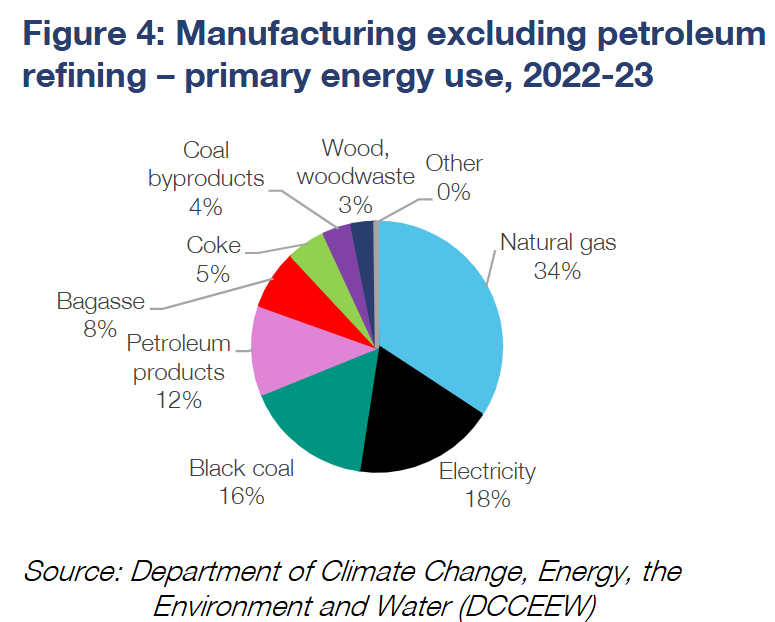

“Manufacturing, excluding the petroleum refining sector, primarily uses natural gas for its energy consumption”, noted Dhar. “Electricity is the second largest energy source, followed by black coal, petroleum products and then more fossil fuels”.

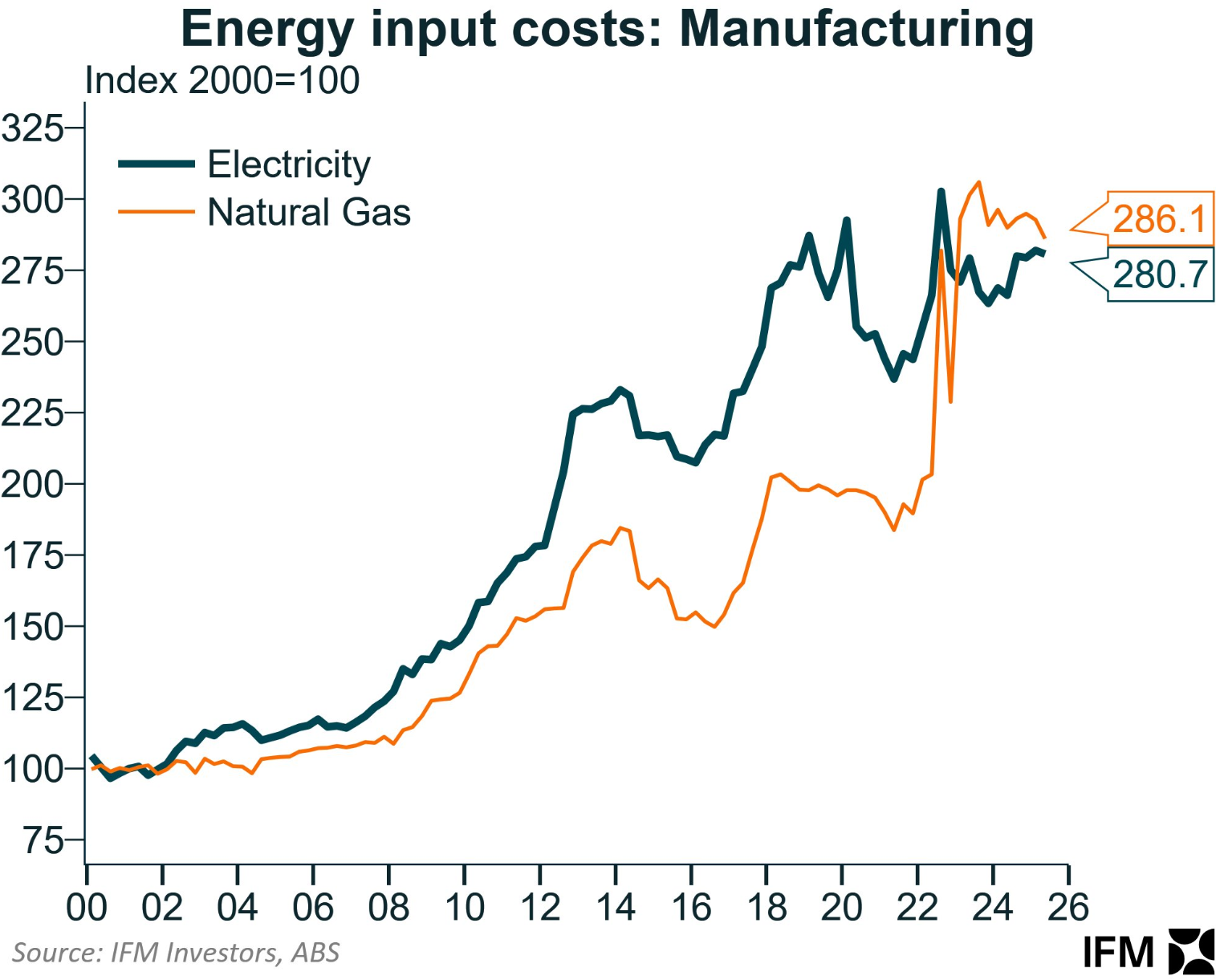

Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors, clearly illustrates these soaring energy costs.

Natural gas input costs used in manufacturing have increased by 186% since 2000, whereas electricity costs used in manufacturing have risen by 181%.

The rise in natural gas costs has been especially brutal since 2022, after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Not surprisingly, then, ASIC insolvency data showed that over 1400 manufacturers nationwide have become insolvent since 2022-23.

Among these, Incitec Pivot, a large fertiliser company, closed its Australian operations due to rising energy costs.

Qenos, Australia’s last major plastics facility, closed in 2024 due to high energy prices, leaving the country fully reliant on polymers supplied from China.

Oceania Glass, Australia’s sole architectural glass firm, closed in February 2025 after 169 years of operation due to soaring energy prices and Chinese dumping.

Orica, the world’s largest manufacturer of mining explosives, chemicals, and agricultural fertilisers, and BlueScope Steel have threatened to shrink their Australian operations and relocate to the United States in response to rising energy costs.

The reality is that without affordable and reliable energy, Australia’s manufacturing sector will continue to contract and the nation will deindustrialise.

Sadly, it is inevitable that energy will become more expensive in Australia.

East Coast Australia’s refusal to implement a domestic gas reservation program is a major contributor to rising energy prices.

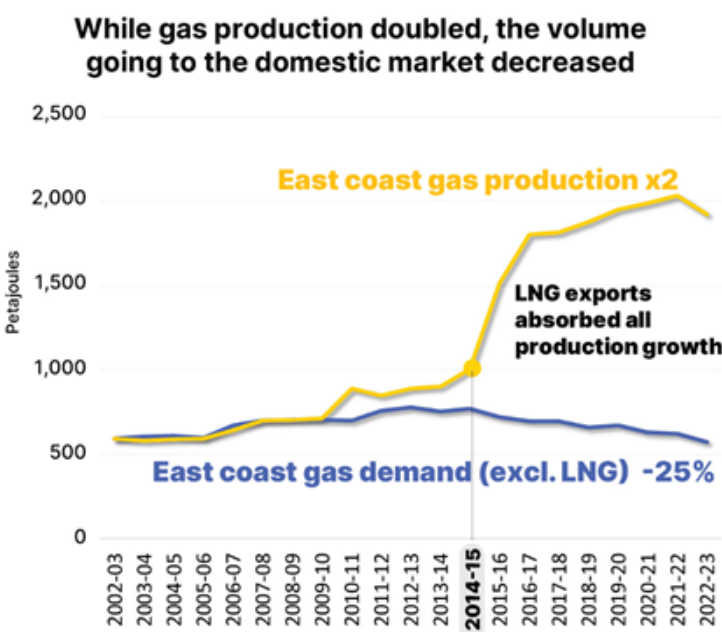

In 2015, the East Coast began exporting natural gas from Gladstone. Since then, the East Coast has doubled its gas production, yet it has delivered 25% less gas to the domestic market.

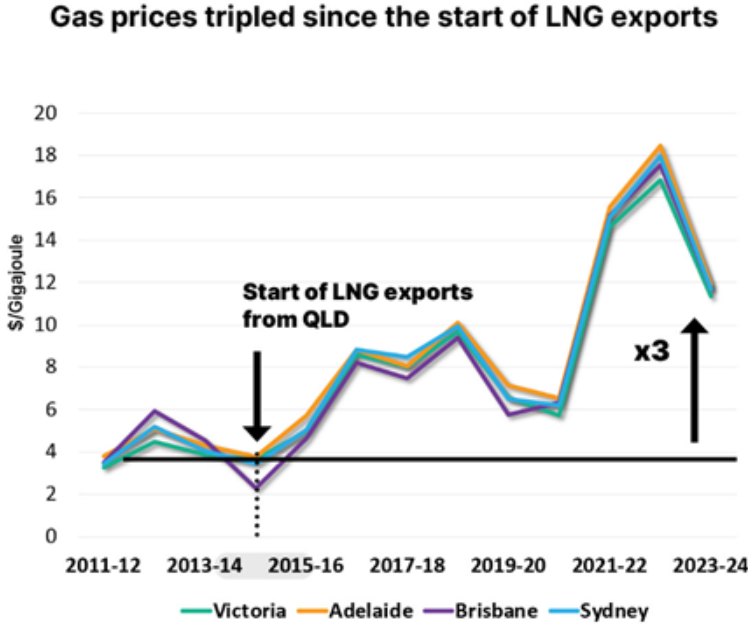

As a result, an artificial shortage of gas has emerged, tripling the East Coast gas price to roughly $12 per gigajoule:

East Coast Australia now has the highest gas prices of any exporting jurisdiction in the world. These high gas costs have contributed to higher power prices, as gas is a primary marginal price setter in the wholesale market.

The situation will only worsen if the East Coast begins importing gas into New South Wales, Victoria, and potentially South Australia to alleviate artificial domestic shortages.

Once liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports commence, East Coast gas prices will skyrocket to import-parity levels of roughly $20 per gigajoule, driving up electricity prices.

Therefore, implementing a domestic reserve scheme on the East Coast is critical for lowering prices and avoiding the negative impacts of LNG imports.

Second, Australia’s mad pursuit of ‘net zero’ and the closure of baseload coal generators will drive up electricity costs.

The many billions of dollars required to build out a web of renewables projects, transmission, and storage will ultimately be capitalised into higher power bills and taxes to pay for subsidies.

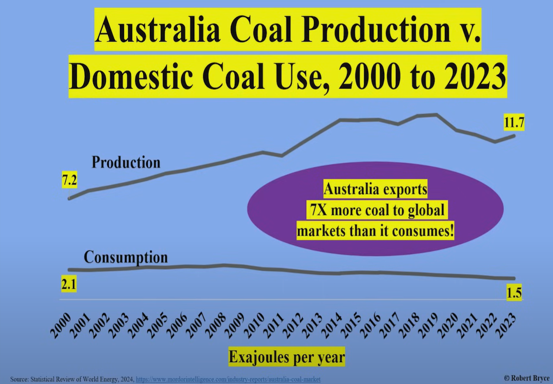

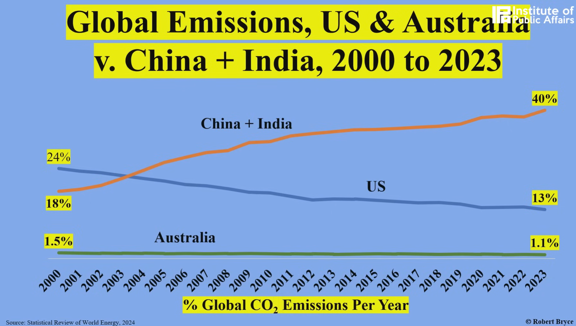

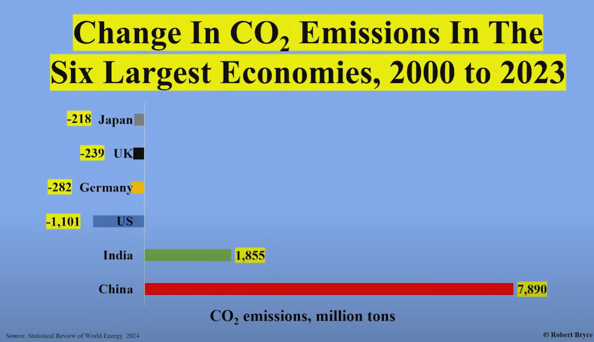

Australia leads the world in coal exports and ranks second in natural gas exports. We export around seven times more coal than we as a nation consume and around four times more gas.

Australia also has the world’s largest endowment of uranium.

Australia, therefore, should have some of the world’s lowest-priced gas and electricity but has instead chosen to deny itself access to this energy while it exports energy security to Asia, including China and India, who are driving the rise in global emissions.

While all Australians will pay for our energy policy failures, the energy-dependent manufacturing sector will suffer the most.

Australia will become even more of an industrial wasteland, with a less diversified and complex economy, lower productivity, and lower living standards.