Australian housing supply cannot keep up with demand

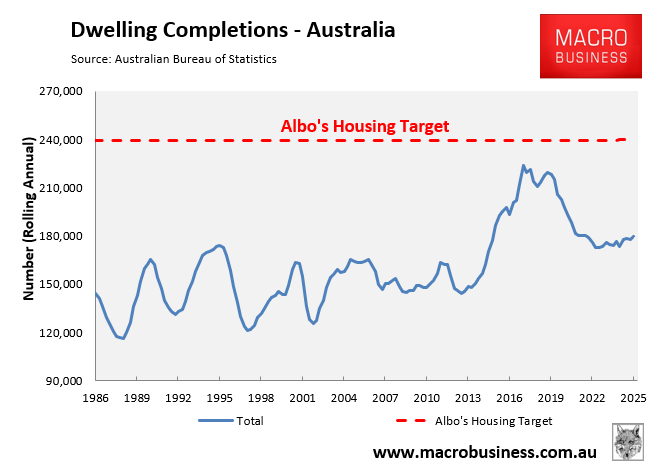

Recall that the federal government has set a fantastical target to construct 1.2 million homes over five years, from 1 July 2024.

This target would require a level of construction that has never been achieved before.

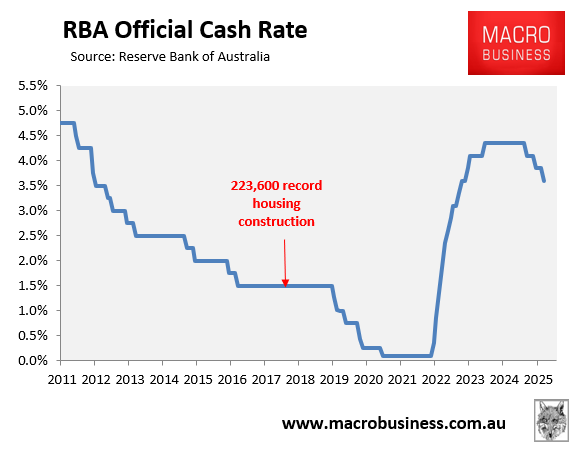

The highest single 12 months of construction in Australia’s history was achieved in Q1 2017 when 223,600 dwellings were built, which was 7% below the government’s annual target, which requires 240,000 homes to be built each year.

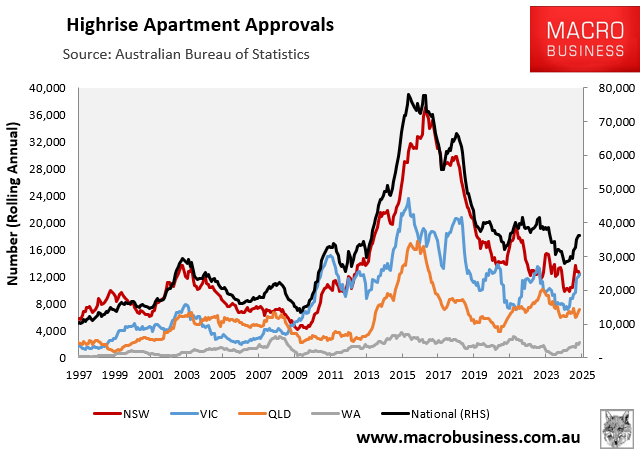

This level of construction was achieved amid a flurry of low-quality and ultimately defective high-rise apartments, many of which have required costly rectification works.

For example, a 2023 NSW government strata report found that more than half of newly registered complexes since 2016 had at least one severe defect, with repair costs averaging $331,829 per building.

The Four Corners report, “Cracking Up,” found a systemic failure to regulate and protect customers despite repeated warnings.

Four Corners and A Current Affair have also reported on the expensive strata fees imposed on high-rise apartment owners.

Regardless, the likelihood of matching, let alone exceeding, the level of construction achieved in 2017 is miniscule, given macroeconomic conditions are far more unfavourable today.

Consider the following data points.

First, interest rates are structurally higher today, 3.6% currently versus 1.5% when the 2017 construction boom took place.

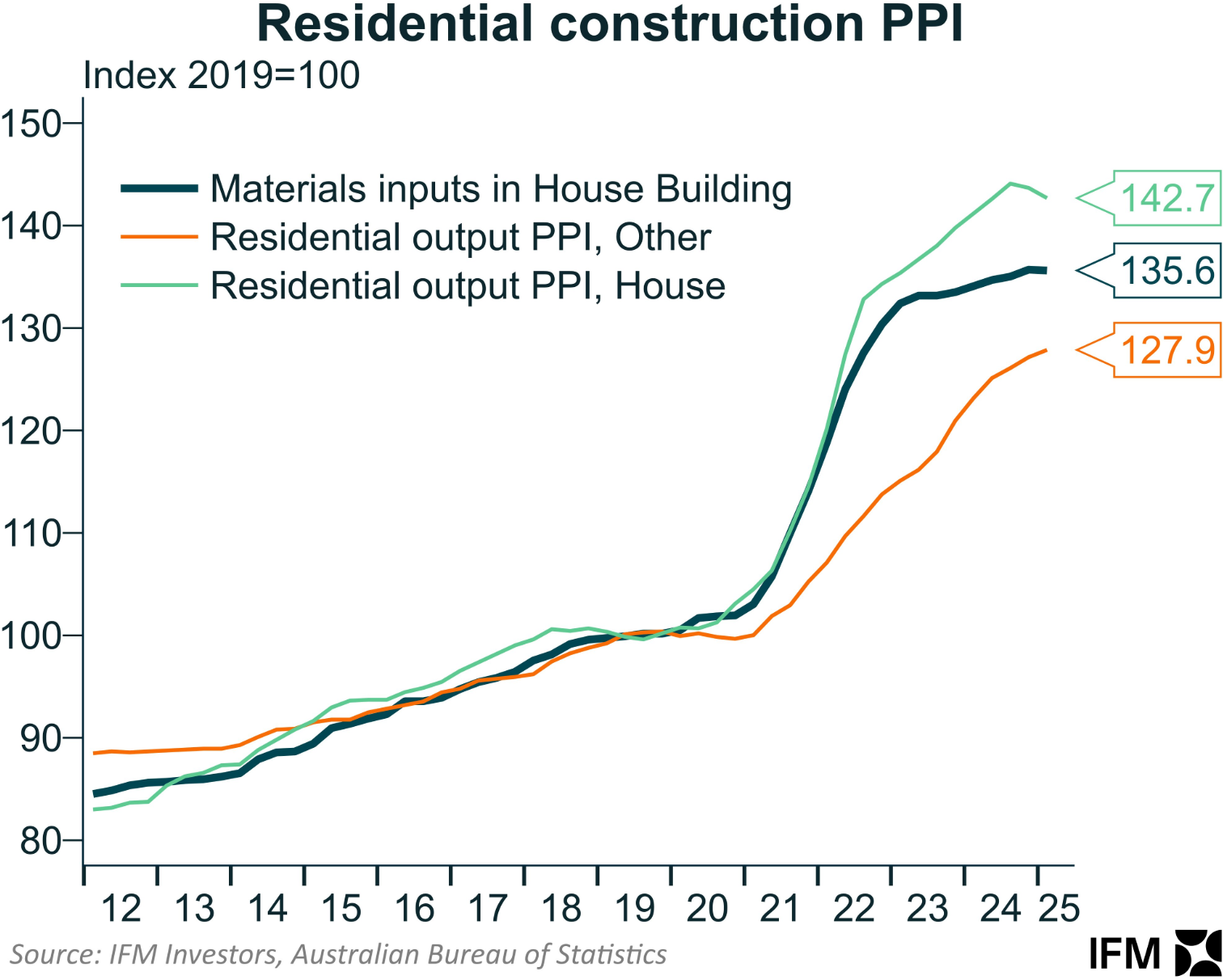

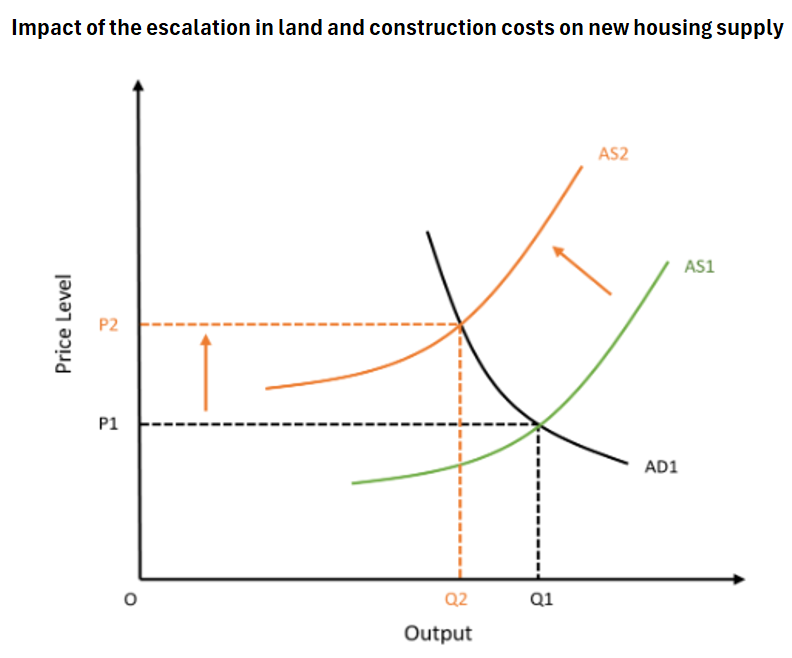

Second, construction costs have increased by around 40% since the pandemic, making new homes substantially more expensive to build than before.

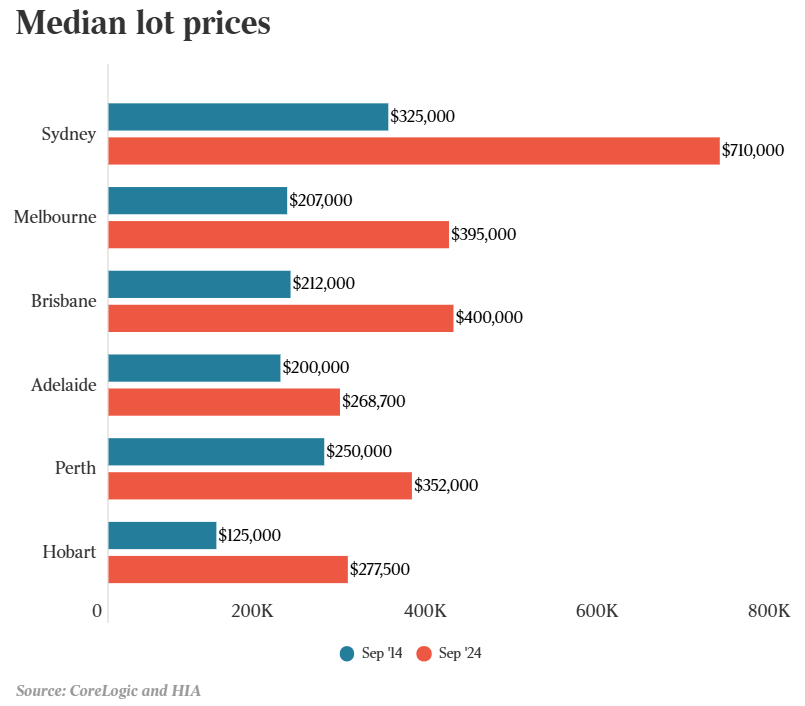

Third, residential lot prices have increased by 37% since the beginning of COVID, according to Cotality, adding to cost constraints.

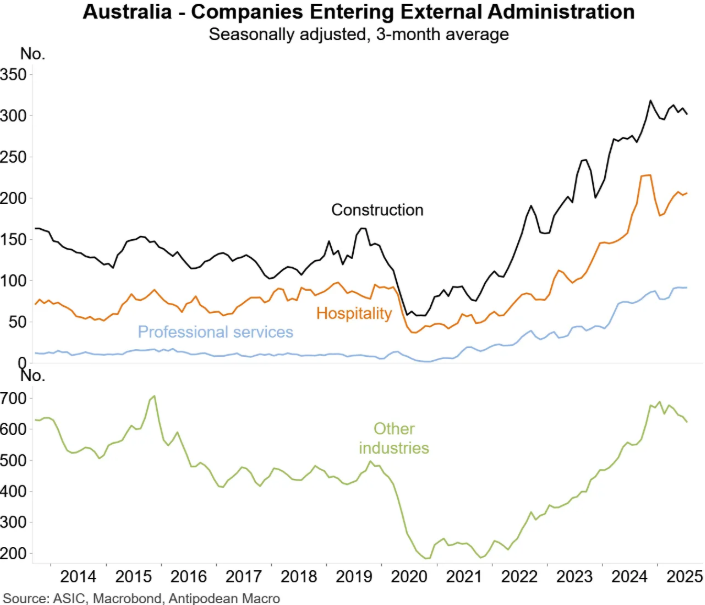

Fourth, a large number of homebuilders have folded due to rising expenses and falling profitability. This has reduced the sector’s capacity to deliver homes.

Finally, homebuilders are competing for workers and materials with government ‘big build’ infrastructure projects, raising costs even higher.

The upshot is that the supply curve for housing has shifted to the left, making it more expensive to build homes at every price point.

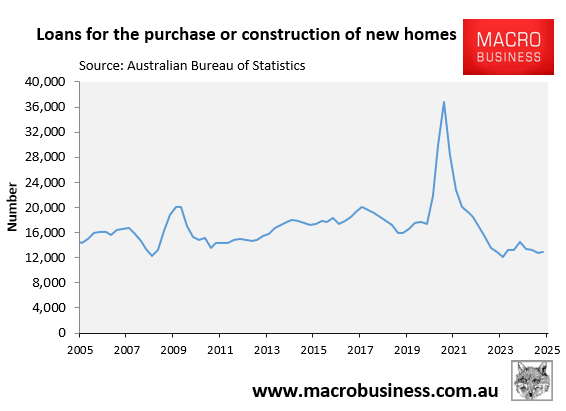

The latest data on new home finance, released last week, highlights the problem. Despite multiple interest rate cuts, the number of loans taken out to construct or purchase a newly built home remains at historical lows:

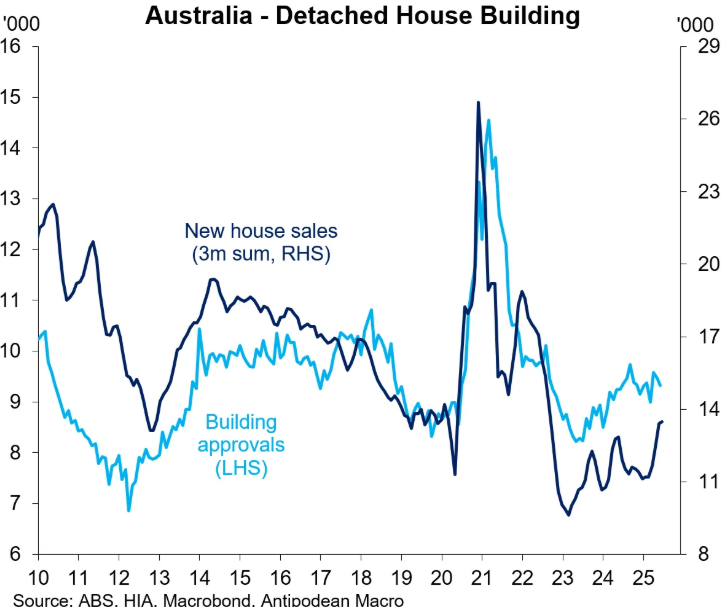

The number of new house sales, presented below by Jutin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, also remains heavily depressed:

The fact of the matter is that with current high immigration settings, housing supply will never keep up with demand.

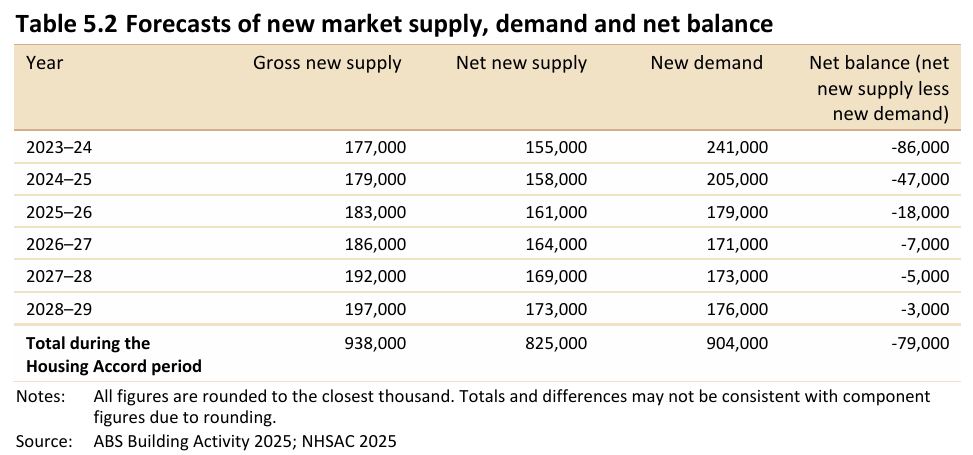

This fact was stated clearly by the federal National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC), which forecast a 79,000 housing shortage over the five-year Housing Accord period.

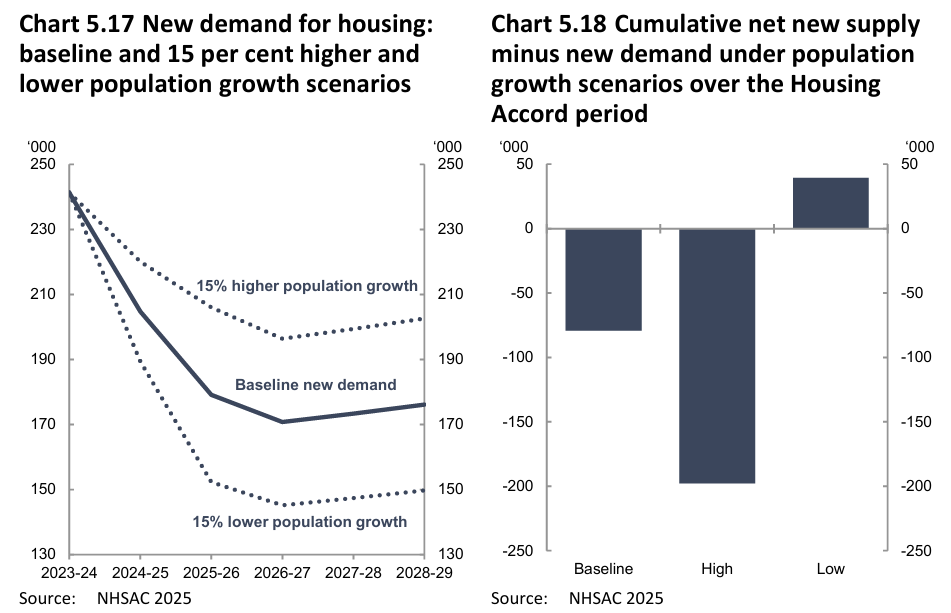

The same NHSAC sensitivity analysis estimated that if the nation’s population grew by only 15% less than forecast over the next five years, then the projected 79,000 shortage would turn into a 40,000 surplus:

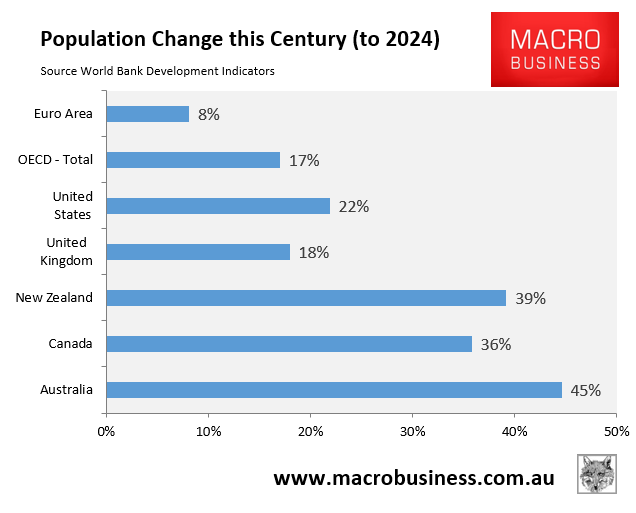

The stark reality is that Australia is experiencing a chronic housing shortage because its population has grown faster than virtually any other developed nation this century.

Therefore, the primary solution to the housing shortage is to match population demand with supply by cutting immigration.

The data is clear.