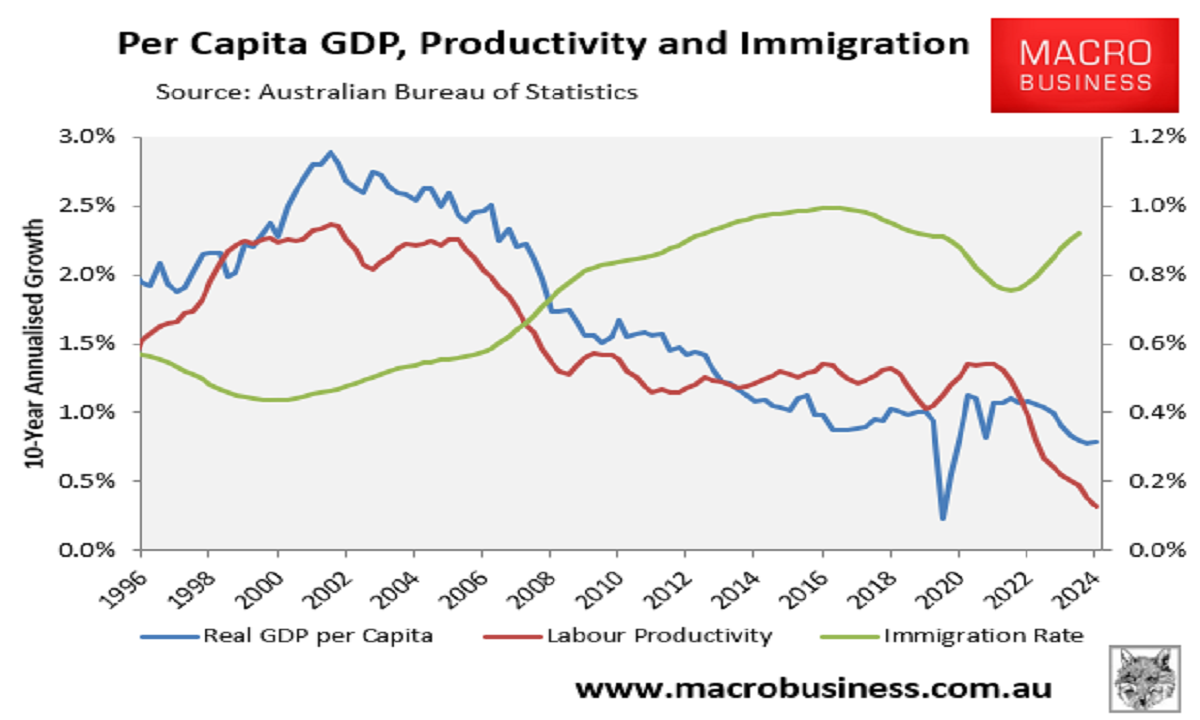

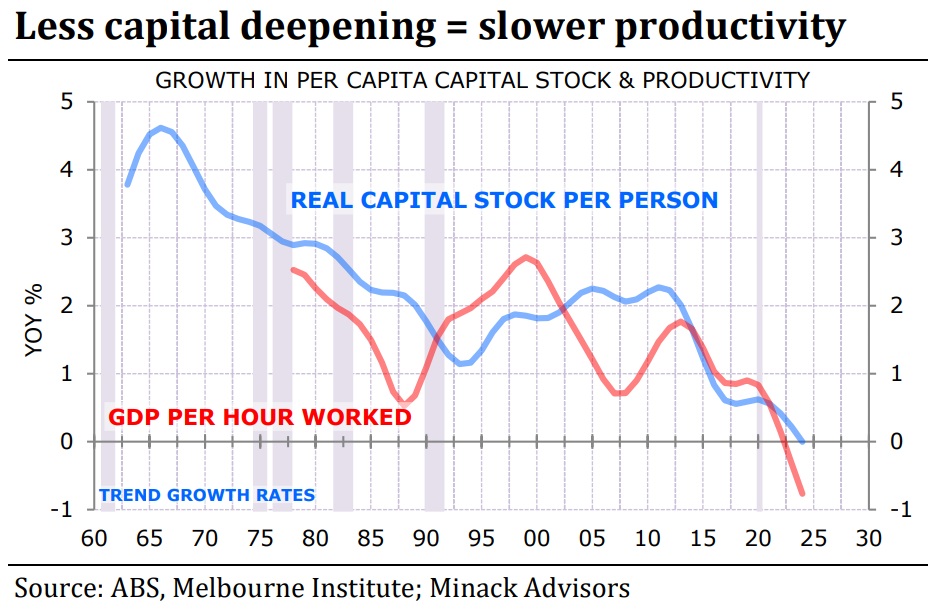

Australia’s economy suffered a lost decade in the 2010s amid the collapse in per capita GDP and productivity growth.

This decade is shaping up as another lost decade, with the economy trapped in a long per capita recession amid the worst labour productivity growth in the advanced world.

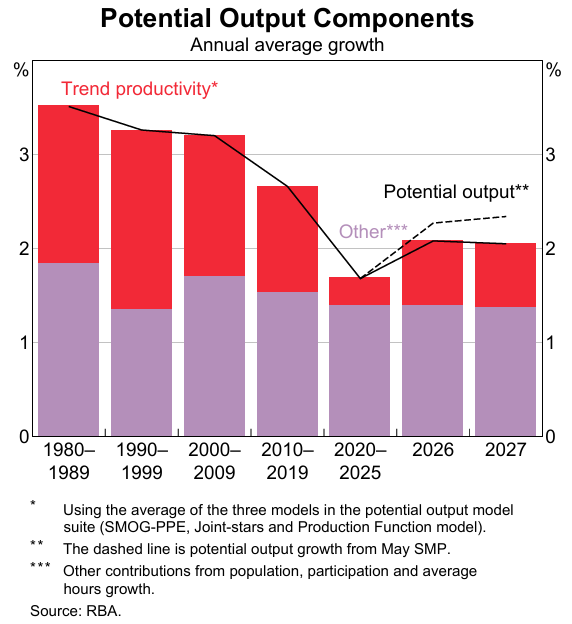

The August Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP) from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) warned that the domestic economy can now only sustain a GDP growth rate of just 2% annually, implying that per capita GDP will barely grow.

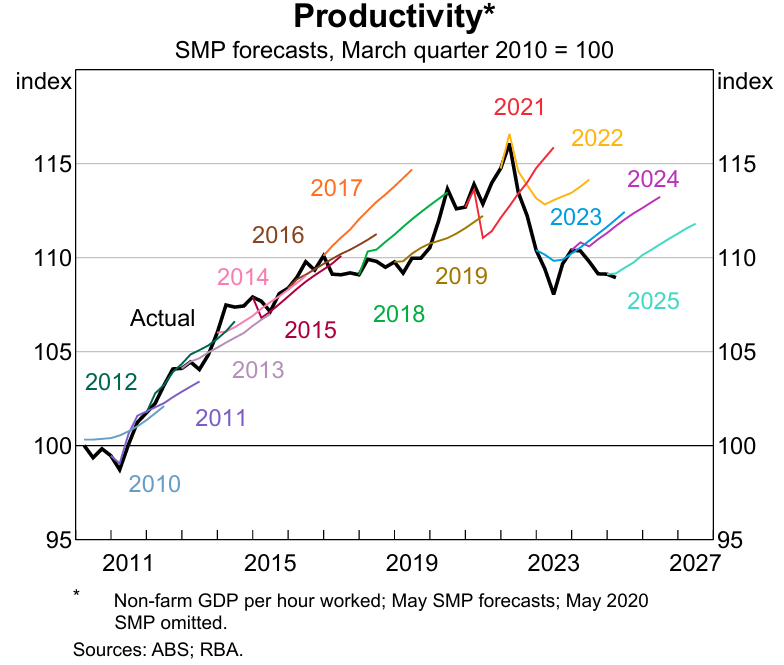

The RBA has been notoriously bullish on Australia’s productivity growth, as illustrated in the following chart:

“For some time, our forecasts have implicitly assumed that productivity growth was temporarily weak and would gradually return to, and be sustained at, higher historical growth rates”, the August SoMP says.

“More often than not, this has not eventuated, resulting in the RBA’s implied productivity forecasts consistently overestimating the actual outcomes”.

The RBA has sharply lowered its forecasts for labour productivity in the August SoMP to just 0.7% per annum, down from its prior forecast of 1.0%.

“Productivity growth is about working smarter, not harder, to produce more in the same amount of time with the same resources”, the RBA SoMP says.

“There is evidence to suggest that this [slower productivity] reflects persistent factors, including declining business dynamism and competition, slower technological diffusion in the economy and lower growth in the amount of capital per worker”.

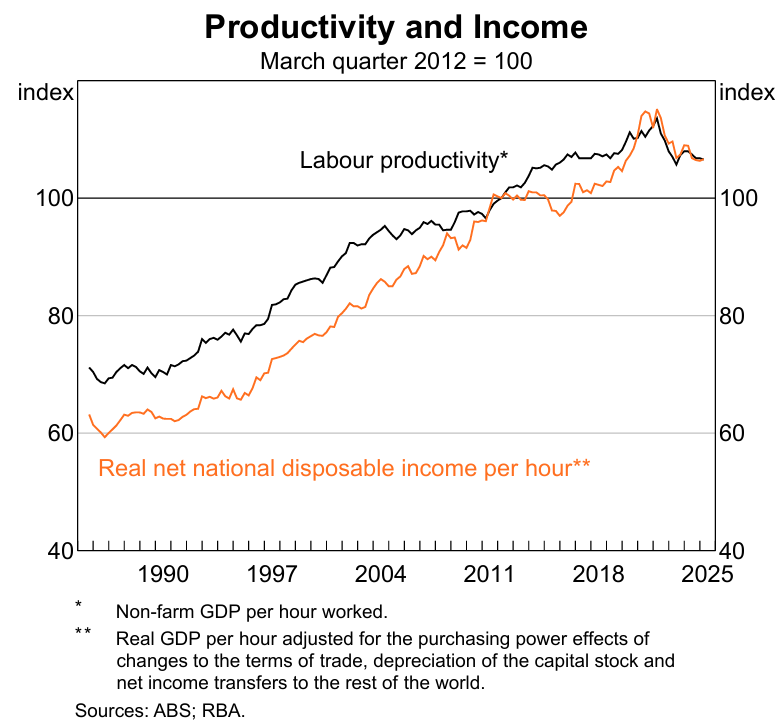

Commensurate with lower productivity growth forecasts, the RBA has also downgraded its forecasts for real wage growth.

“Productivity growth is the key driver of real wages growth in the long run as it allows for wages to increase without the (real) costs faced by firms rising”, the RBA SoMP reads.

“As such, we assess that the rate of wages growth over the long term that is consistent with inflation at the target and the labour market at full employment is equal to the midpoint of the inflation target plus productivity growth”.

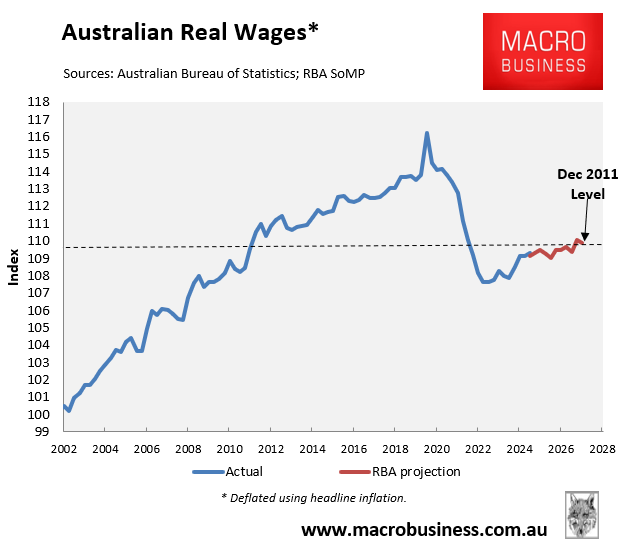

The following chart plots Australia’s forecast real wages to the end of 2027:

By Q4 2027, Australian real wages are forecast to still be 5.5% below their Q2 2020 ‘covid-bubble’ peak, tracking at around Q4 2011 levels.

One of the key shortcomings of the RBA’s productivity analysis is that it fails to discuss the role played by excessive immigration in lowering productivity growth and ergo living standards.

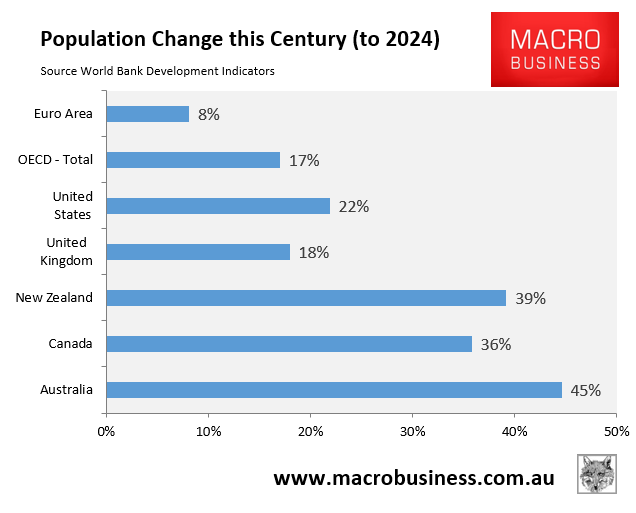

World Bank data shows that Australia has experienced the strongest population growth this century, courtesy of abnormally high net overseas migration.

However, net business, infrastructure, and housing investment have failed to keep pace with the ballooning population, resulting in lower productivity per worker.

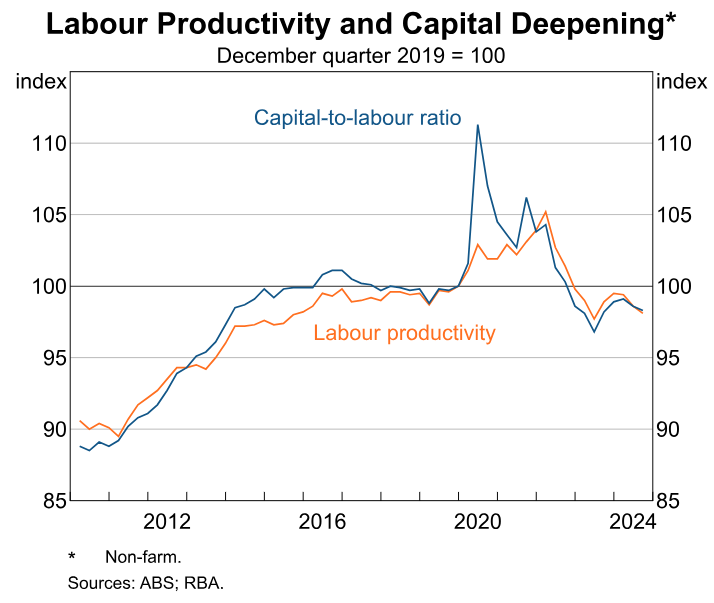

Australia’s capital-to-labour ratio is tracking at the same level as 2013:

Running a high immigration program without the requisite business and infrastructure investment inevitably results in less capital per worker and lower productivity.

It also means that Australians will need to work longer to earn a given level of income.

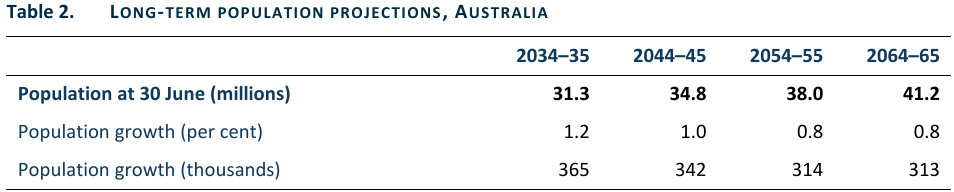

Given that the Centre for Population projects that Australia’s population will balloon by 13.5 million over the next 40 years—equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane:

Source: Centre for Population

There is simply no way that Australia will add sufficient business and infrastructure investment, meaning that the nation’s capital stock will continue to “shallow” and productivity growth will remain moribund.