Australia’s ‘miracle’ labour market has been living in somewhat of a fool’s paradise.

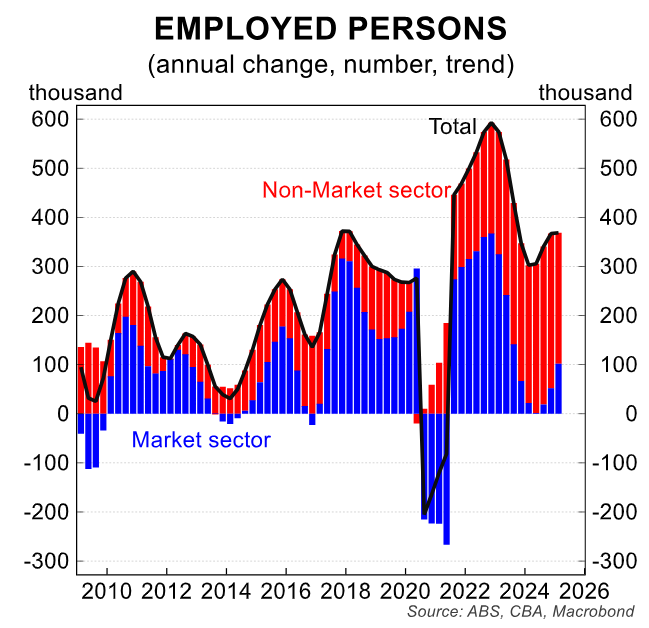

A boom in government-funded jobs has driven Australia’s strong job growth and historically low unemployment rate.

The non-market sector, which comprises public and private service providers that rely on government funding, has accounted for 60% of total job creation since the pandemic and 80% of job creation over the past two years.

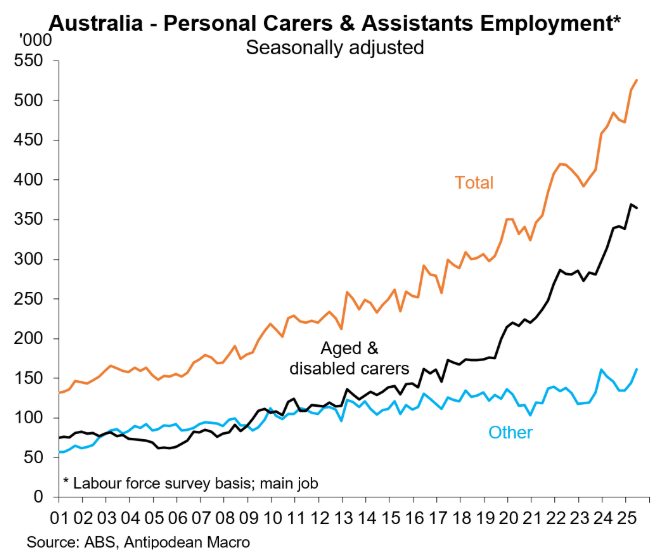

This non-market job growth has been driven by the $52 billion blowout in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), which has fueled the creation of carer jobs.

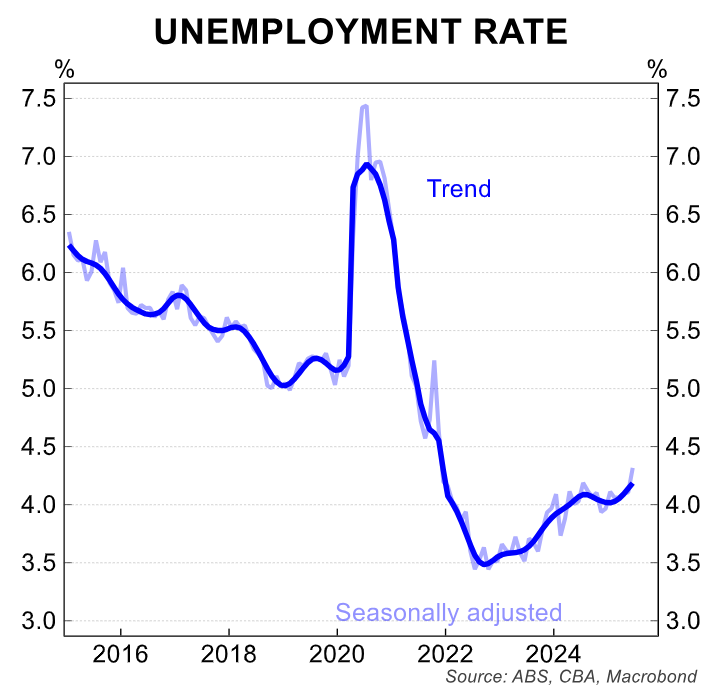

Thursday’s labour market report for June from the ABS suggested that Australia’s labour market ‘miracle’, buoyed by government-funded jobs in areas like the NDIS, might be over.

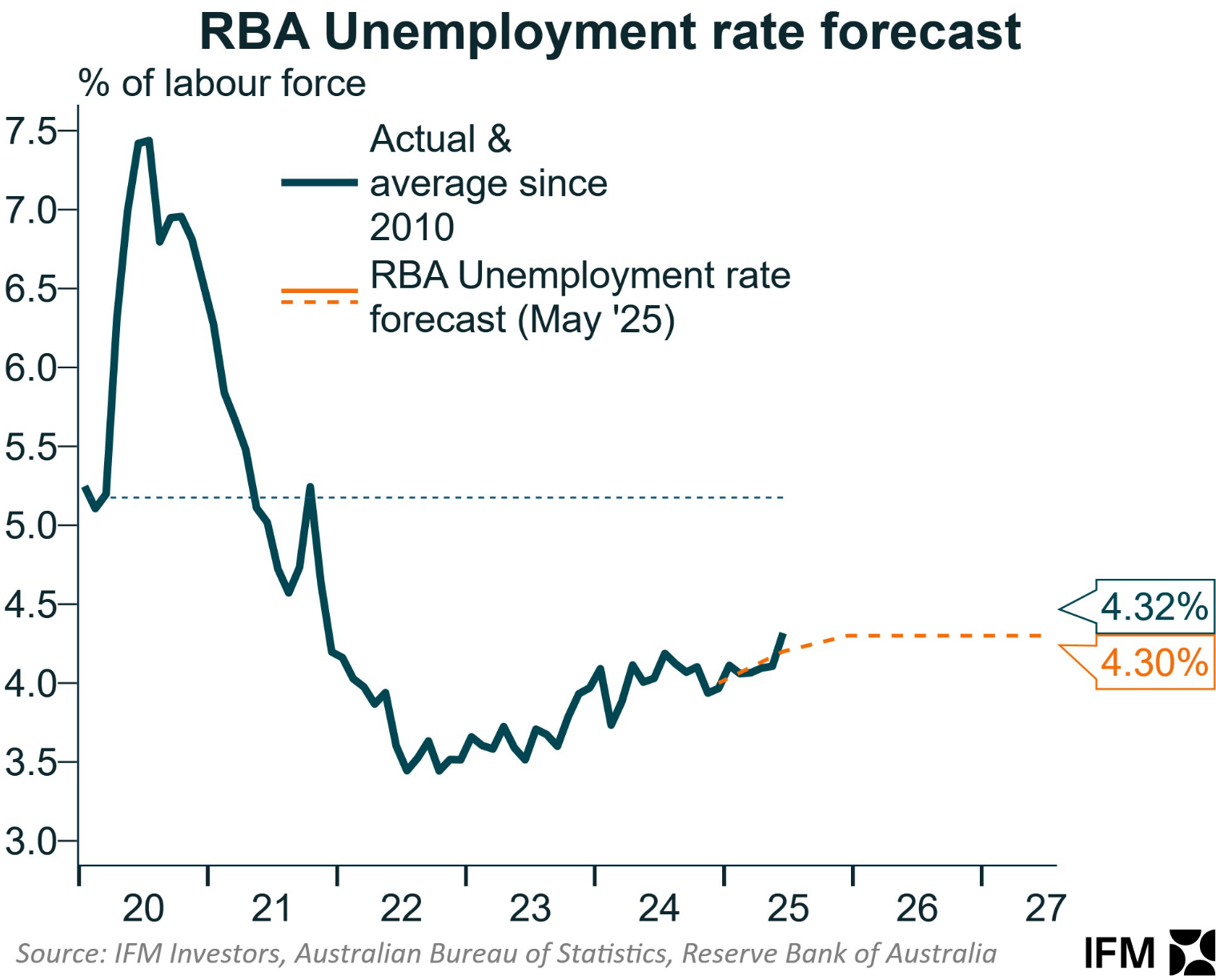

Australia’s unemployment rate lifted to 4.3%, which was the highest rate since November 2021.

The outcome exceeded the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) expectations for the cycle, increasing the possibility of a rate cut in August.

Full-time employment declined by 38,200, while underemployment rose 0.1% and hours worked fell by nearly 1%.

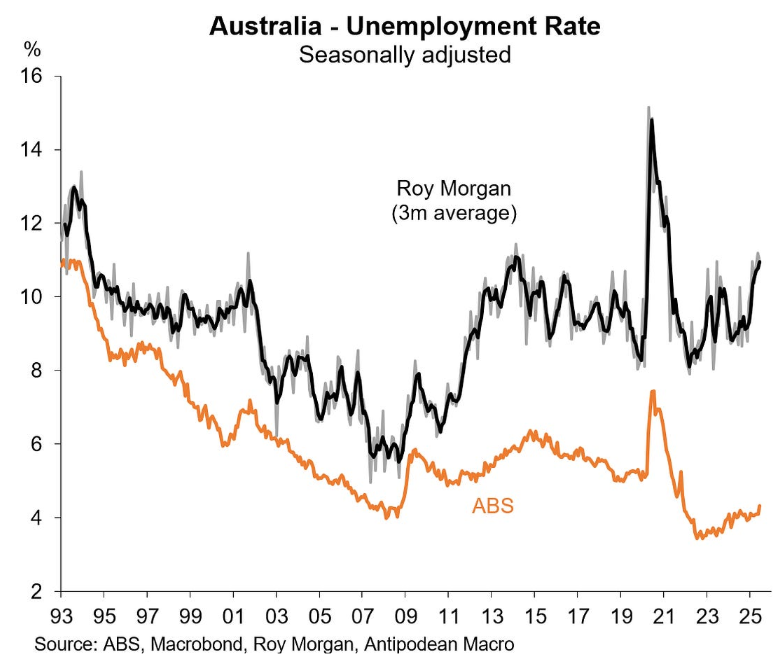

Roy Morgan’s shadow unemployment survey has also been pointing to higher unemployment for some time.

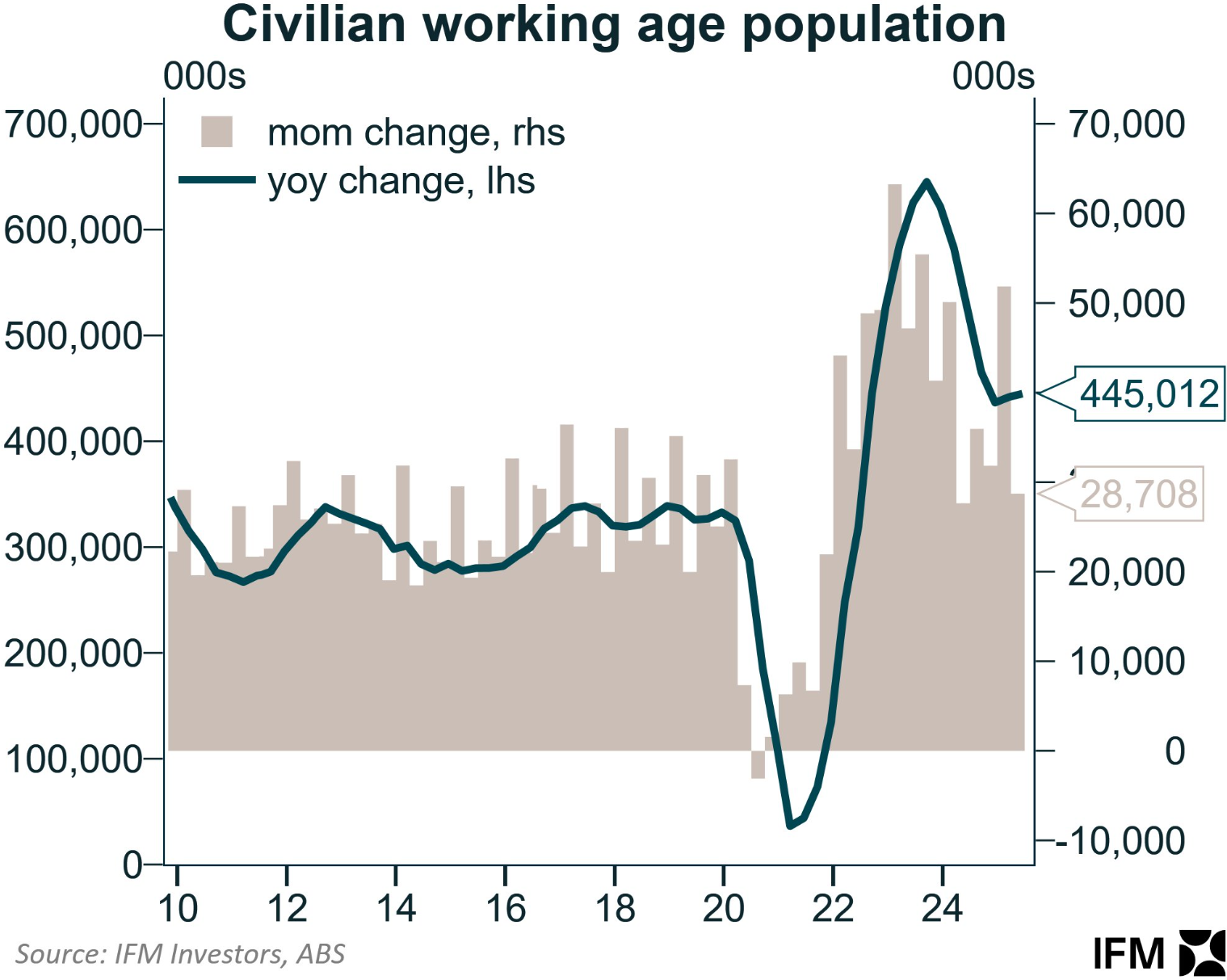

Softening labour demand has arrived at the same time as Australia’s labour supply continues to grow at a strong rate courtesy of historically high net overseas migration.

Australia’s working age population grew by 445,000 in the 2024-25 financial year.

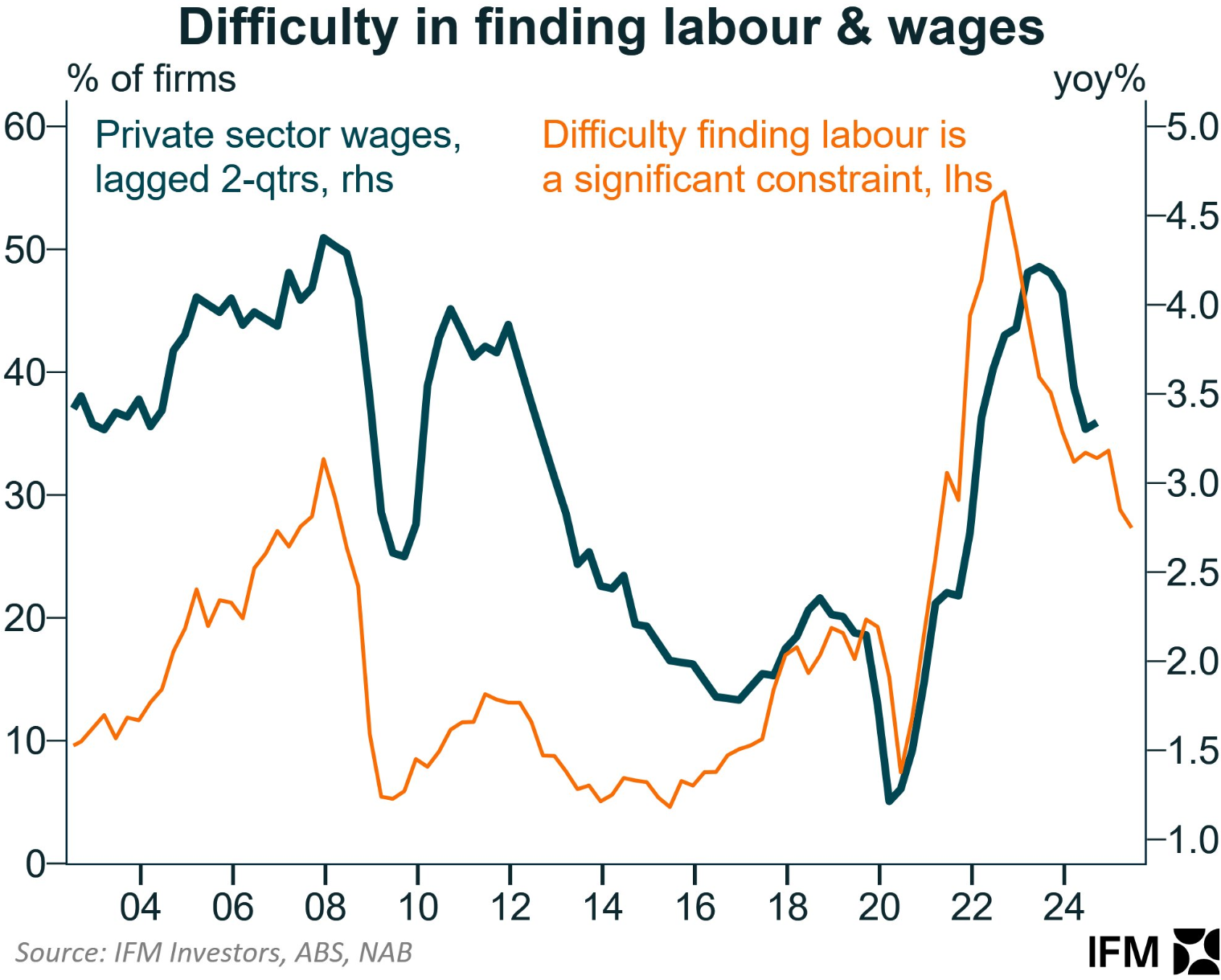

A weakening labour market is also bad news for wages.

Australians have experienced a record 6.1% decline in their real wages. Worse, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) own forecasts suggest that real wages will only recover to December 2011 levels by mid-2026, by which time they will still be tracking 5.7% below their mid-2020 peak.

Rising unemployment typically means lower wage growth, owing to the rising supply of available workers.

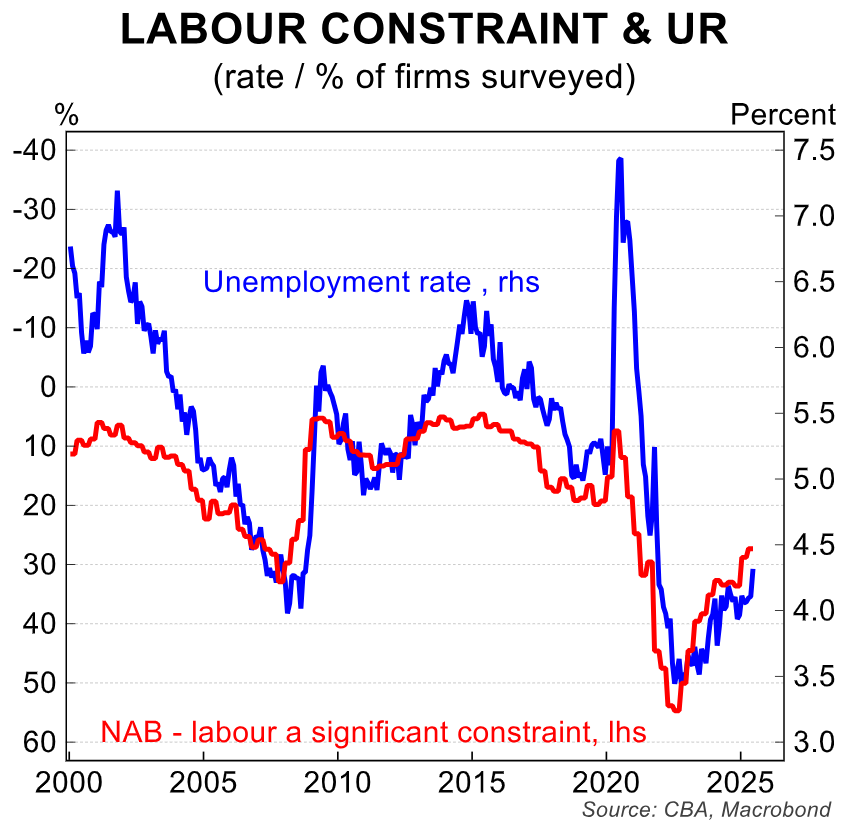

Meanwhile, Thursday’s NAB Quarterly Business Survey showed that the proportion of businesses finding the availability of labour as a significant constraint on their business has declined in line with the unemployment rate.

All of which suggests that wage growth will stall, thwarting the expected weak recovery in real wages.

The federal government should cut immigration to bring labour supply in line with demand and housing demand in line with supply.

Silver lining: Lower interest rates:

The only upside is that an interest rate cut at the RBA’s August monetary policy meeting looks like a certainty. Only a very strong CPI print would prevent a rate cut.

I discussed these issues in detail on Saturday’s Treasury of Common Sense on Radio 2GB/4BC.