How Indian students game the visa system

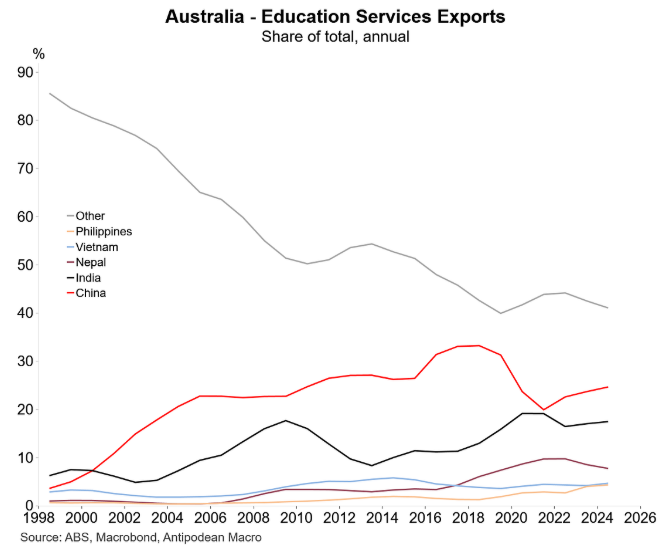

The mix of Australia’s international student enrolments has shifted dramatically during the last two decades.

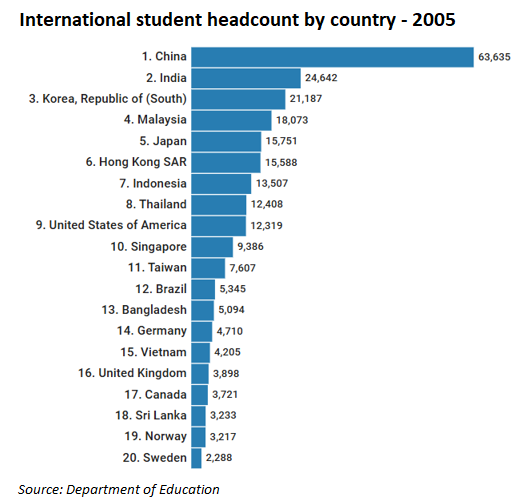

In the January-April period of 2005, 288,579 overseas students were studying in Australia, according to the Department of Education.

China (63,635) led enrolments, with India (24,642) coming in a distant second. The Department of Education did not even mention Nepal.

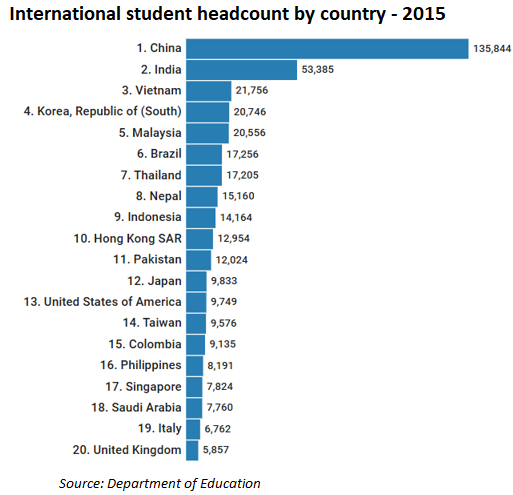

A decade later, in January-April 2015, 497,221 international students were studying in Australia.

China (135,844) remained the clear leader, with India (53,385) trailing far behind. Nepal (15,160) also moved up in the rankings to eighth place.

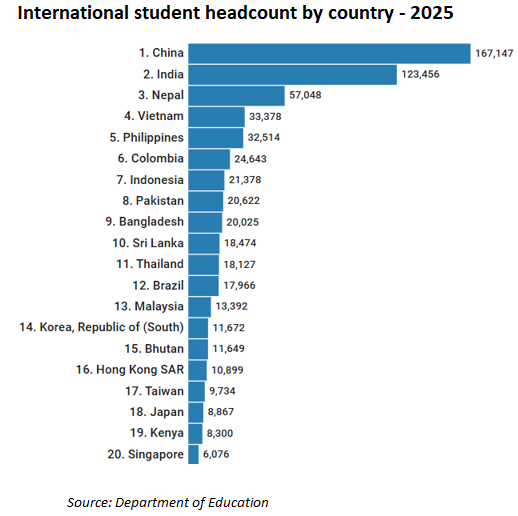

Fast forward another decade to January-April 2025, and 723,265 international students were studying in Australia.

Although China continued to have the most international students in Australia (167,147), the number of Indian (123,456) and Nepalese (57,048) students had significantly increased in second and third place.

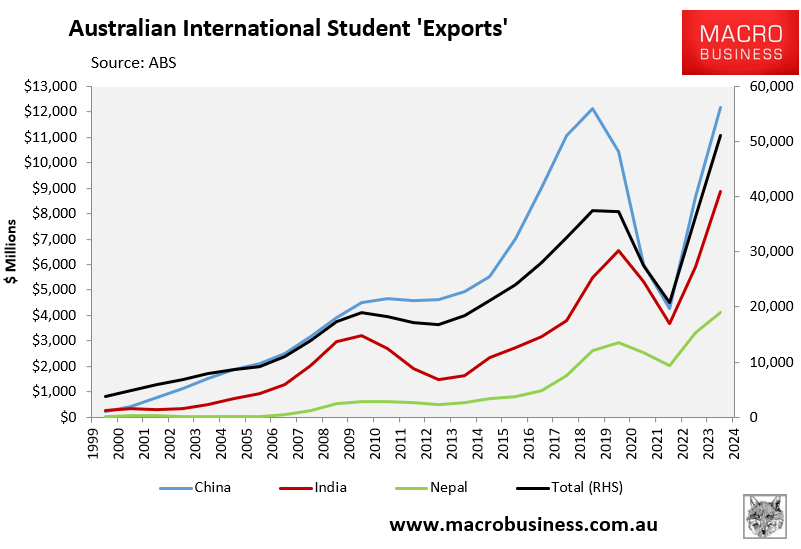

The same is true for education exports, which are counted as spending on products and services in Australia, regardless of the source of money.

In 2023-24, China ($12.2 billion) has the highest share in education exports, followed by India ($8.9 billion) and Nepal ($4.1 billion).

According to Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, education exports from India and Nepal have surged, particularly after 2018.

Consider the data points below:

- In 2005, China accounted for 22% of educational exports. By 2024, the percentage had risen to 24%.

- In 2005, India contributed 9% of all education exports. By 2024, the percentage had climbed to 17%.

- In 2005, Nepal contributed less than 1% of education exports. By 2024, that share had risen to 8%.

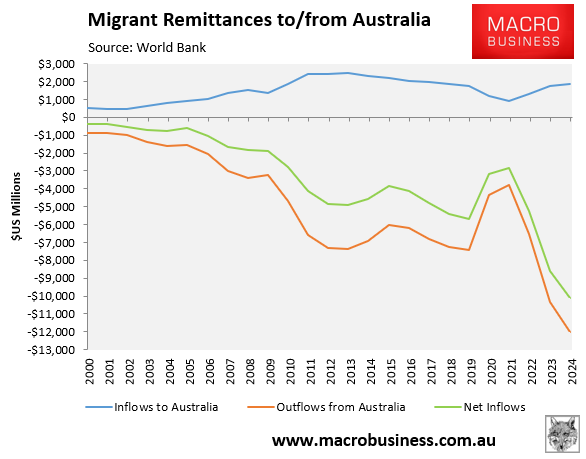

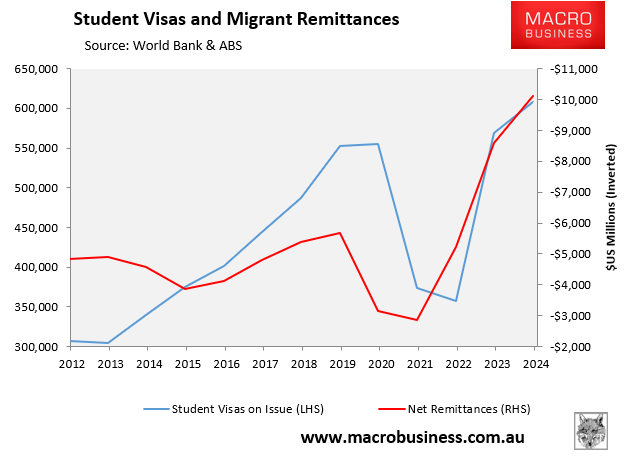

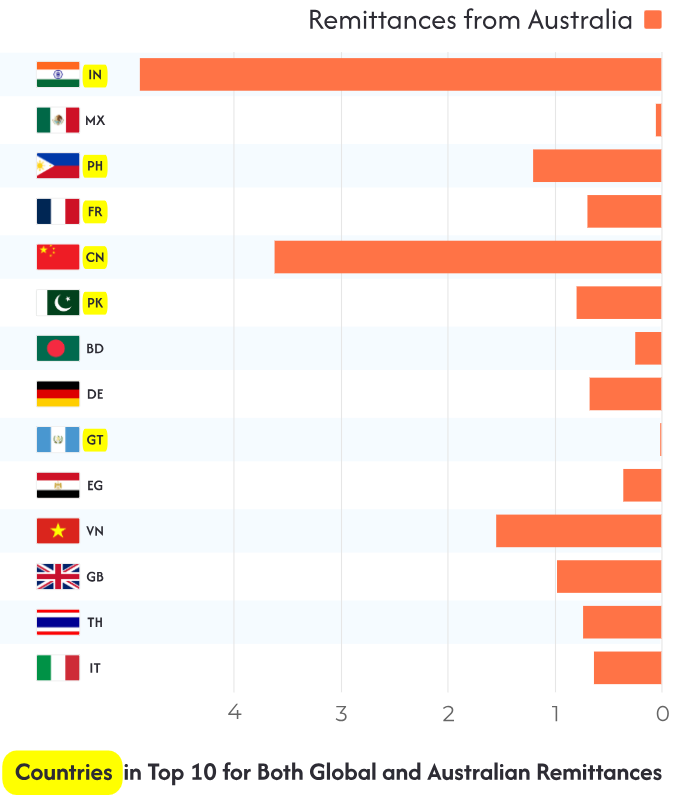

However, as explained last week, India dominated the $US10.1 billion (circa $A15 billion) in net migrant remittance outflows from Australia in 2024.

As illustrated below, net remittance outflows have closely tracked the volume of international students.

A report by Money Transfer Australia, which drew on data from the World Bank, ABS, KNOMAD, and DFAT, estimated that US$4.8 billion worth of remittances were sent to India from Australia in 2024.

Source: Money Transfer Australia

“Money Transfer Australia’s report highlights that migrants from India are among the most active senders of money, despite the diversity of Australia’s overseas-born population”.

These net remittance outflows should be treated as an import and deducted from the education export figure, which is already overinflated because it does not subtract expenditure derived from money earned in Australia.

Meanwhile, Indian Link projected that remittance outflows to India will continue to rise as the migrant population expands in Australia, driven by international education.

According to a Navitas study intentions poll conducted in 2022, students from South Asia and Africa choose a study destination based on their capacity to gain job rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency.

South Asian and African students prioritise employment and migration over education quality.

Students from these two continents are less concerned about educational quality.

In fact, with the exception of students from China and Europe, all source nations placed a high value on the potential to work while studying and post-study employment opportunities.

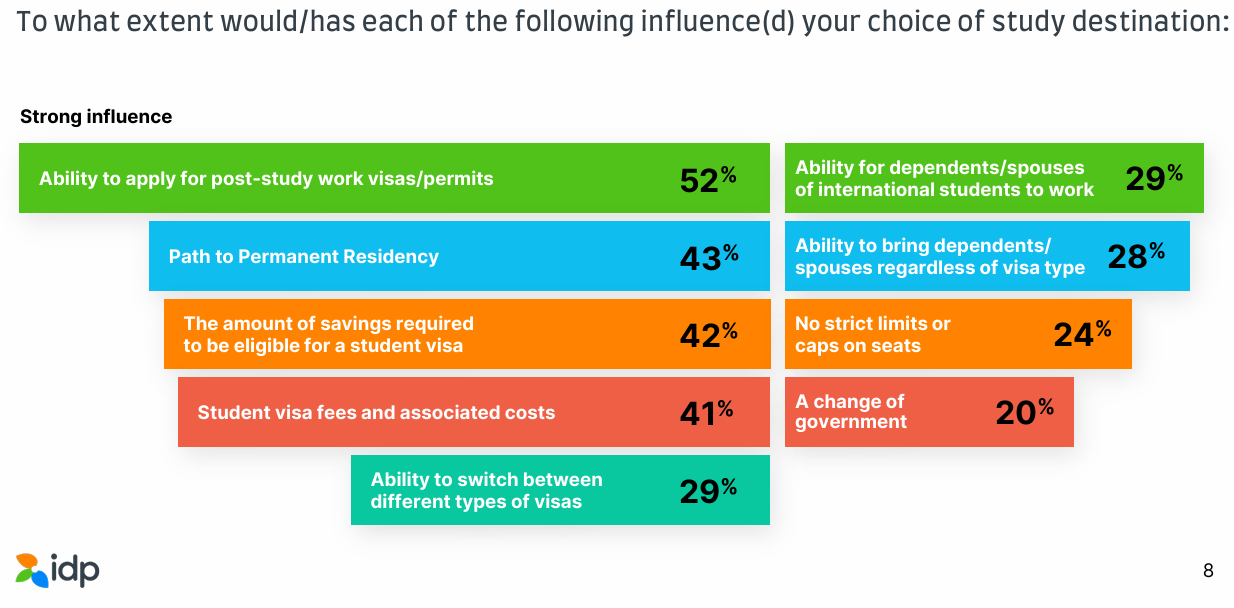

According to the most current IDP Emerging Futures survey, post-study work rights (52%) were the most important factor for international students when deciding where to study. Pathways to permanent residency were placed second with 43%.

A survey by Allianz Partners Australia suggested that 68.4% of international students plan to remain in Australia long-term.

It should be no surprise, then, that Australia has witnessed the greatest increase in student numbers from nations that rely on paid employment, whereas only one-fifth of Chinese students work in jobs while studying in Australia.

Clearly, the concept of education ‘exports’ only really applies to Chinese students, who mostly pay their tuition and living expenses using money from China rather than income earned in Australia. They also send proportionately less money home via remittances.

Ravi Lochan Singh, managing director, Global Reach, explained how Indian or Nepali students actively game Australia’s student visa system to gain entry into the country:

“Australia is currently facing a significant issue where students use higher ranked or low-risk universities (as categorised by Home Affairs) to secure their student visas easily and then after the first semester of studies, the students get moved to private colleges offering higher education degrees,” Singh told The PIE News.

According to Singh, while such moves, often made by Indian or Nepali students with the help of onshore immigration agents, may be genuine, they “waste” the efforts of offshore education agents and universities that initially recruited the students.

Various migration pacts signed between Australia and India have facilitated the growth of Indian students and graduates by enhancing opportunities to study, work, and live in Australia. These include:

- The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA), signed by the former Coalition government.

- Australia-India Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement, signed by the current Labor government.

- The Mechanism for Mutual Recognition of Qualifications, signed by the current Labor government.

Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan also visited India in September 2024, grovelling for more Indian students.

Meanwhile, Indian students and migration agents celebrated Labor’s federal election victory because they know that it means easier entry into Australia:

“It’s big, big news for all international students, which means more chances, more work rights, better support are on the way”, one man said in a viral clip shared on Twitter (X).

“So if you are planning to stay or study in Australia, this is your moment, OK? Just tighten your seatbelts and consider Australia for your future. Congratulations”.

“No more $5000 international student visa fees, no more international student visa cut each year, no more international student visa issues”, another man said. “It’s great news for everybody”.

Australia’s policymakers and media should drop the charade and acknowledge that international education is an immigration racket.