Later this year will be the 28th anniversary of the signing of the Kyoto Protocol, which saw an agreement struck to pursue emissions reductions and stabilisations.

In the almost three decades since, the decline of thermal coal demand has been forecast repeatedly, only for demand to surge to new heights, largely driven by dramatic increases in consumption in China and India.

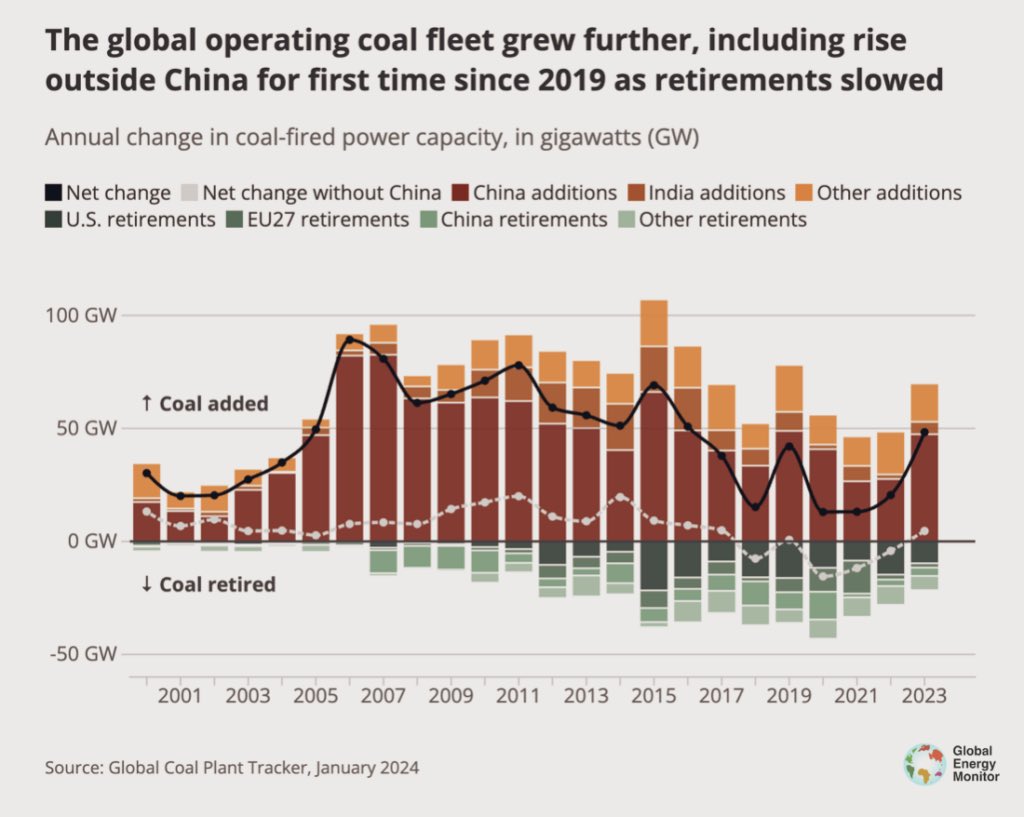

According to an analysis by Global Energy Monitor, the world has continued to add coal-fired electricity capacity in net terms every year so far this century.

The 2023 calendar year saw the largest net rise in coal-fired electricity capacity globally since 2016.

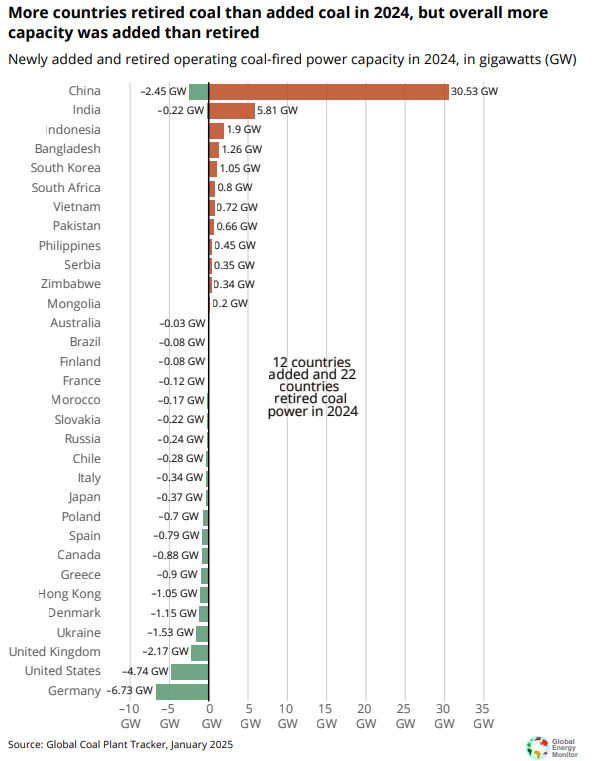

When looking at the granular breakdown, the trend is clear: the developing world, particularly China and India, continues to add to coal-fired capacity, while the developed world continues to close coal-fired power stations.

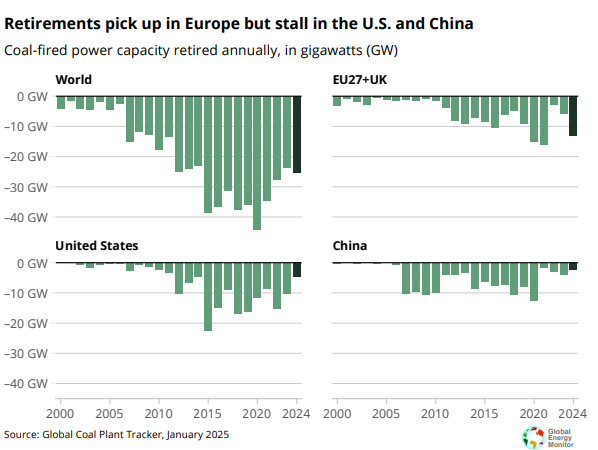

Meanwhile, the peak annual rate of reduction in coal-fired power station capacity occurred back in 2020 and has since decelerated significantly.

For years, the longevity of growing demand for thermal coal has been an expected boon to Australia’s fortunes.

But in the coming years, that’s set to change.

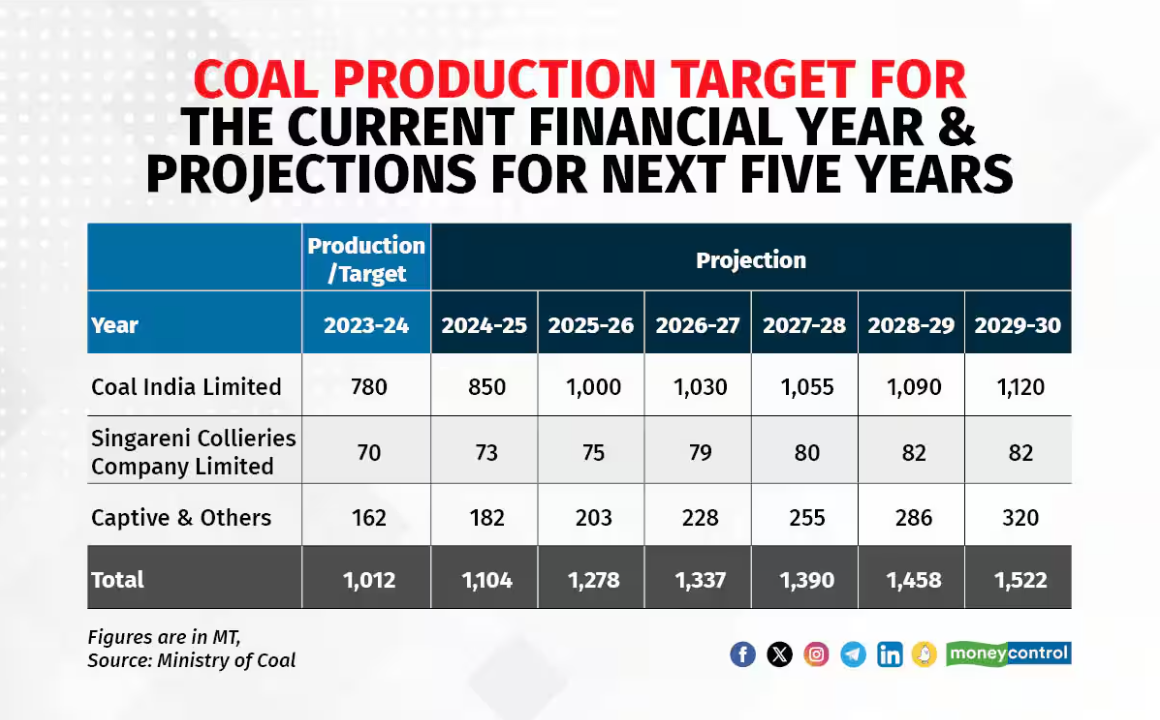

According to projections from the Indian Ministry of Coal, domestic coal production is set to rise by over 50% on 2023-24 levels by 2029-30.

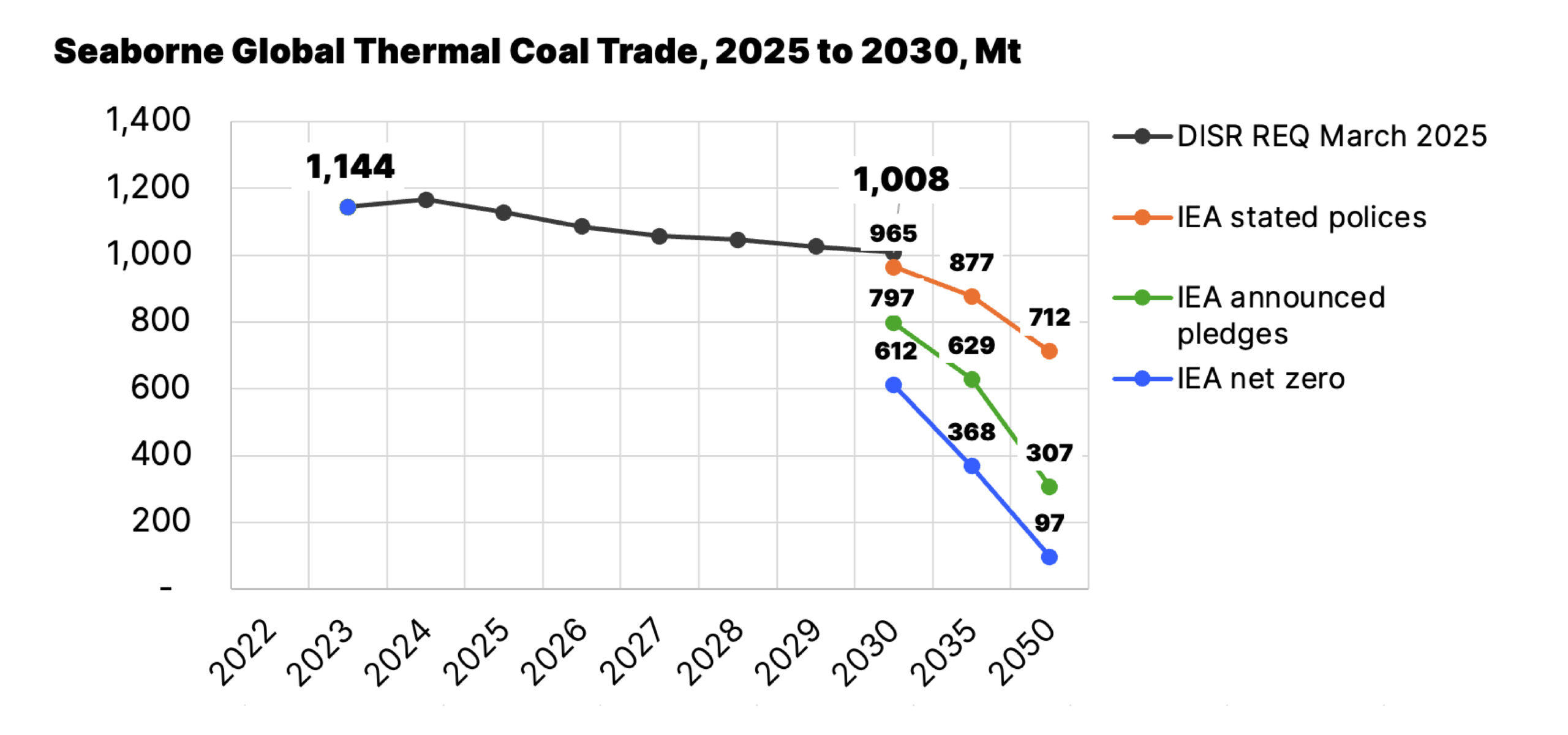

Yet despite the expected surge in Indian coal consumption and China continuing to bring additional thermal coal-fired power stations online for years to come, figures from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis project that we are currently in the midst of peak demand for seaborne coal exports.