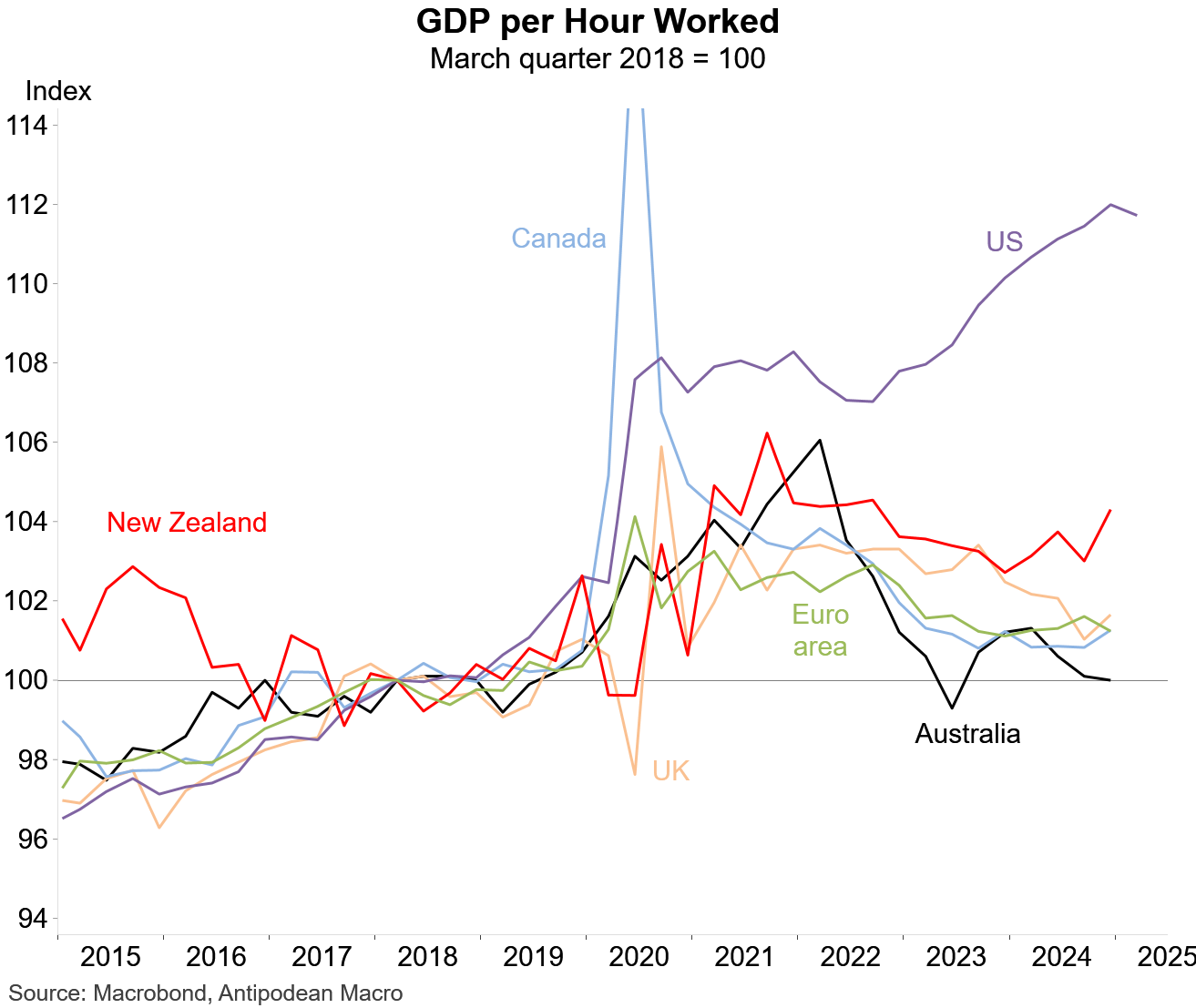

As shown by the following chart from Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, Australia’s recent productivity growth has been among the worst in the advanced world.

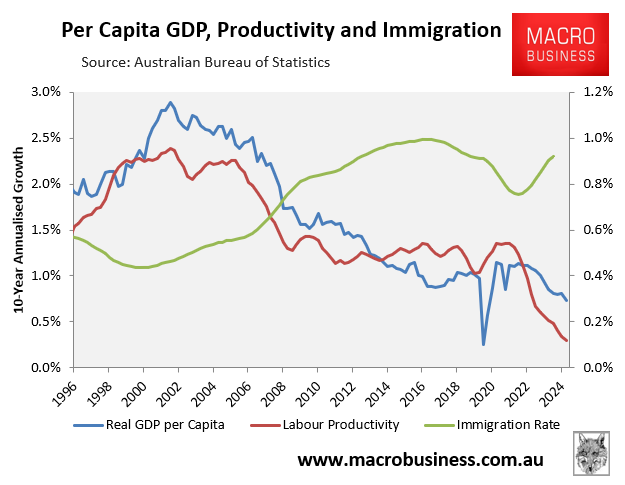

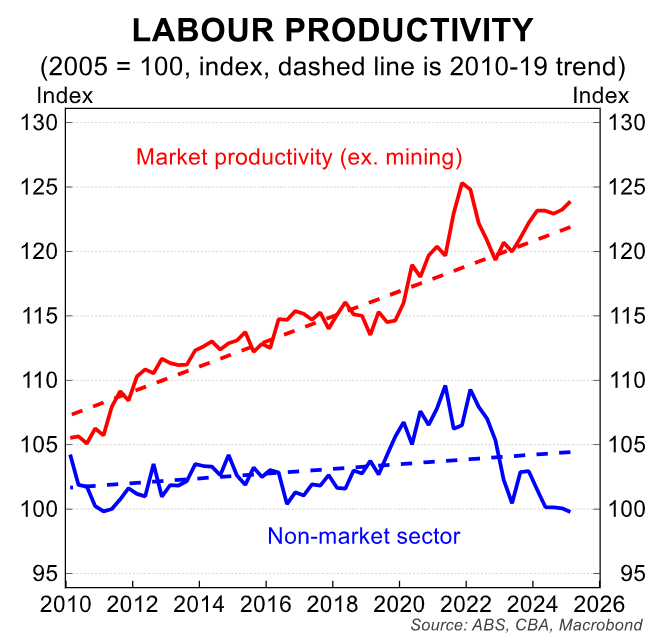

Australia’s labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) has experienced virtually zero growth since 2016.

Reasons for the productivity decline:

I attribute Australia’s poor productivity performance to four main factors.

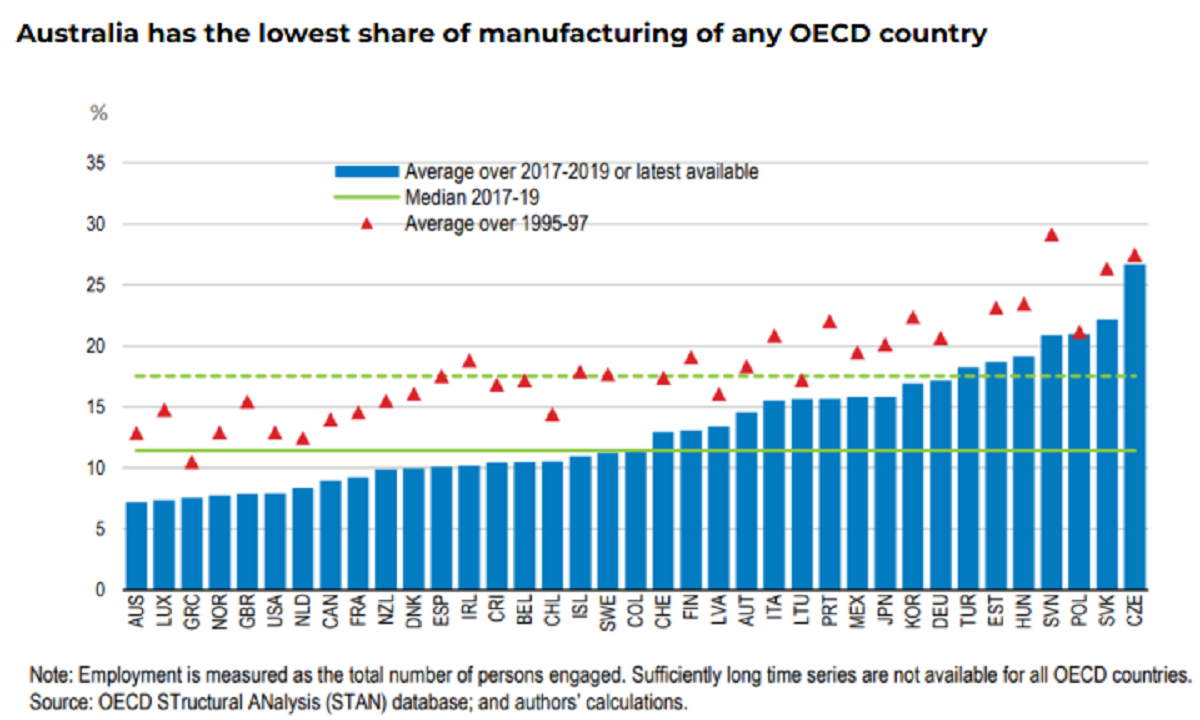

1) Deindustrialisation

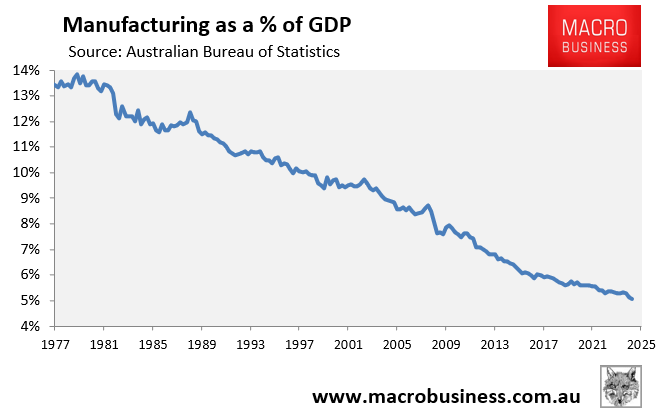

Australia’s economy has deindustrialised, with its manufacturing sector shrinking to around 5% of the economy, the lowest share in the OECD.

Australia’s manufacturing share was around 14% in 1980 and around 10% at the turn of the century.

Manufacturing is subject to global competition and relies on capital investment and technological advancements. As a result, it has historically been the industry with the highest productivity increase.

Therefore, the manufacturing sector’s share in the economy has shrunk, so too has Australia’s productivity.

The reasons for the decline in manufacturing are multifaceted and include:

- The removal of tariffs from the 1980s;

- The inexorable increase in the Australian dollar following the start of the mining boom in the 2000s, which made Australian manufacturing less competitive; and

- More recently, the surge in energy costs (gas and electricity) has made manufacturing more expensive and less competitive.

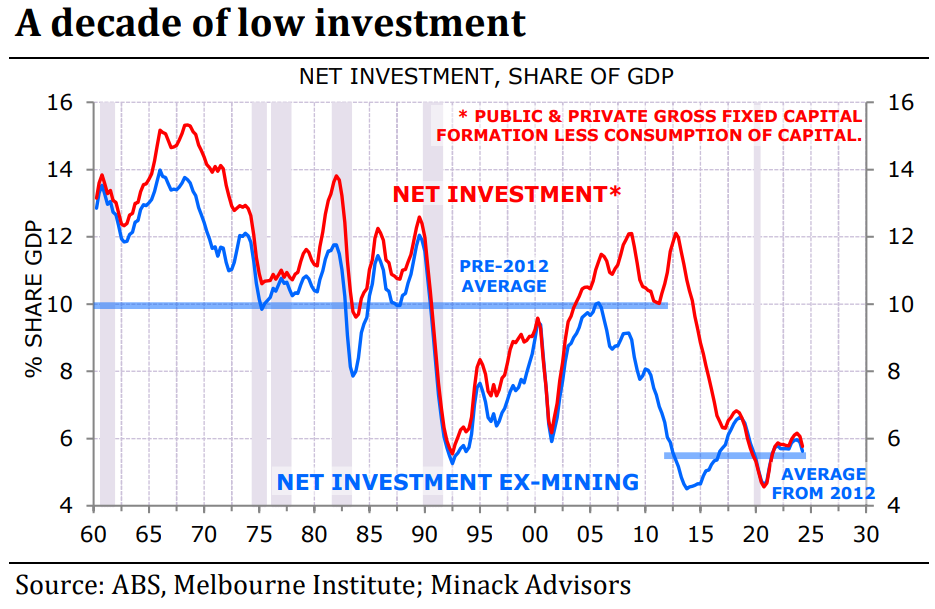

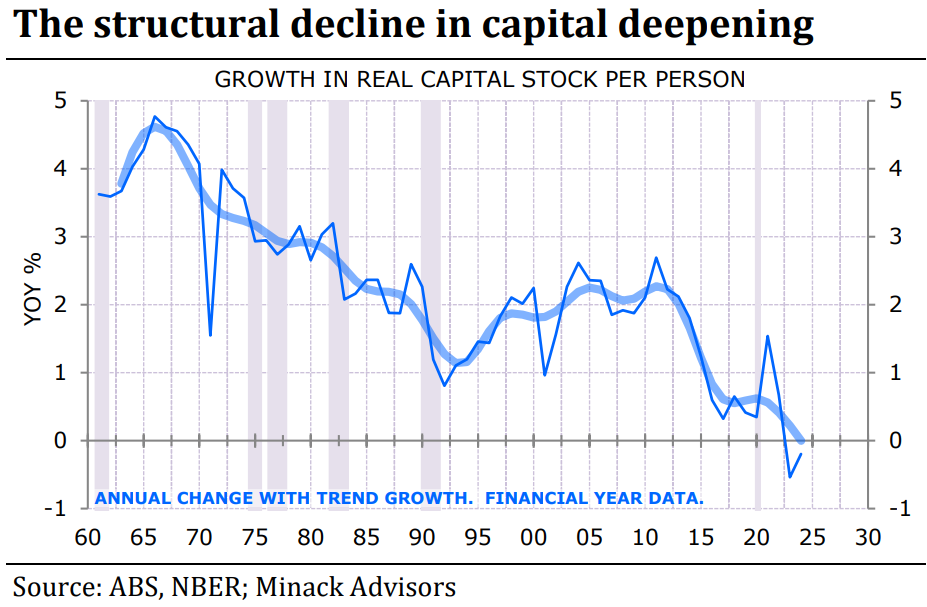

2) Capital shallowing:

Capital deepening, i.e., an increase in the capital-to-labour ratio, was the main driver of Australia’s productivity growth in the post-war period.

Net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession.

Population growth has put a strain on this low investment spending.

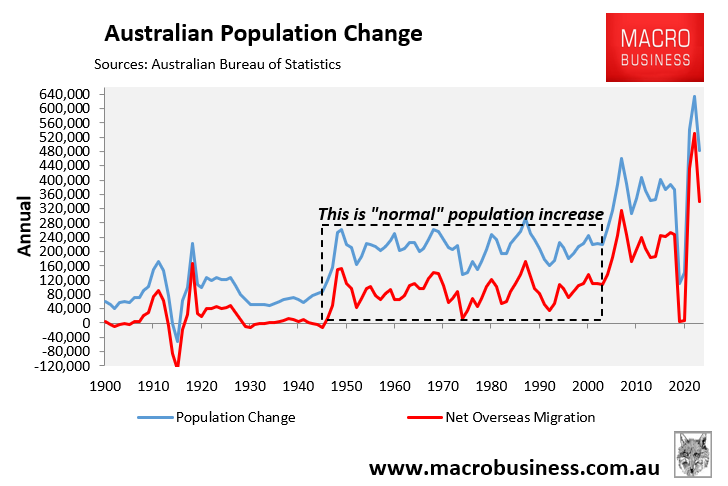

The federal government massively increased net overseas migration in the mid-2000s.

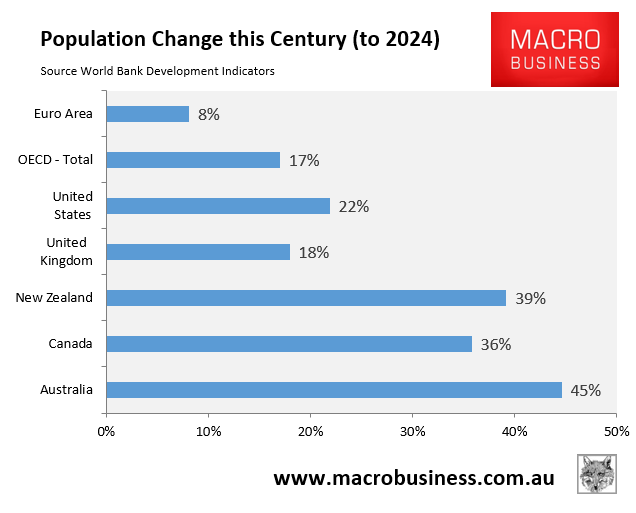

Australia’s population has increased by 8.7 million so far this century, the fastest rate of growth in the advanced world.

As a result, Australia’s population expanded much faster than business, housing, and infrastructure investment, leaving workers with less capital, resulting in “capital shallowing” and lower productivity growth.

Australia is caught in a productivity trap mainly because the federal government has operated a permanently high migration program over business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

Arguably, Australia’s franked dividend system has encouraged lower business investment by encouraging companies to pay out dividends instead of reinvesting in the business or in capital investment.

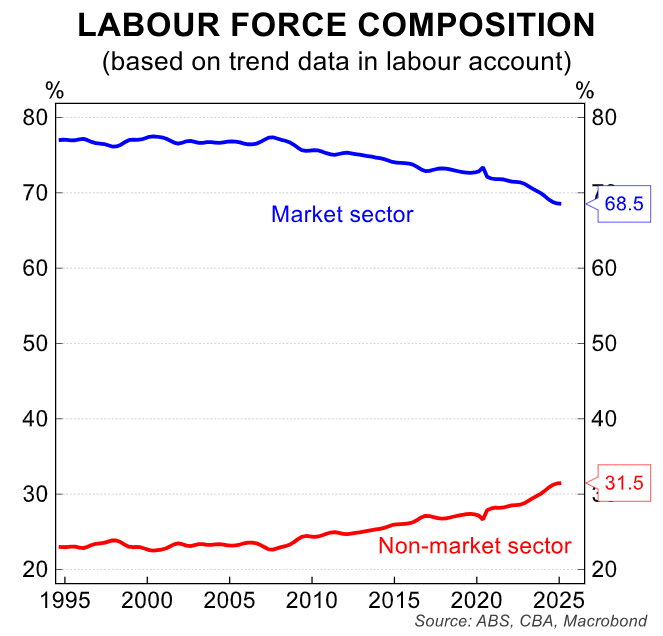

3) Explosive growth in the non-market economy:

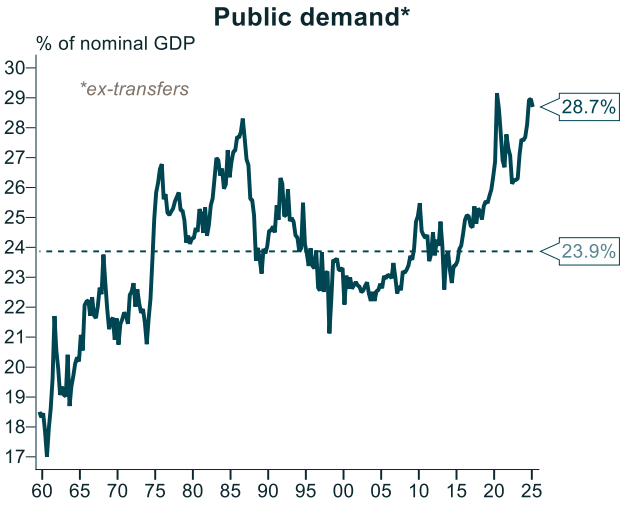

Excessive government spending, which was a near record 28.7% of GDP in Q1 2025, is the third driver of Australia’s productivity stagnation.

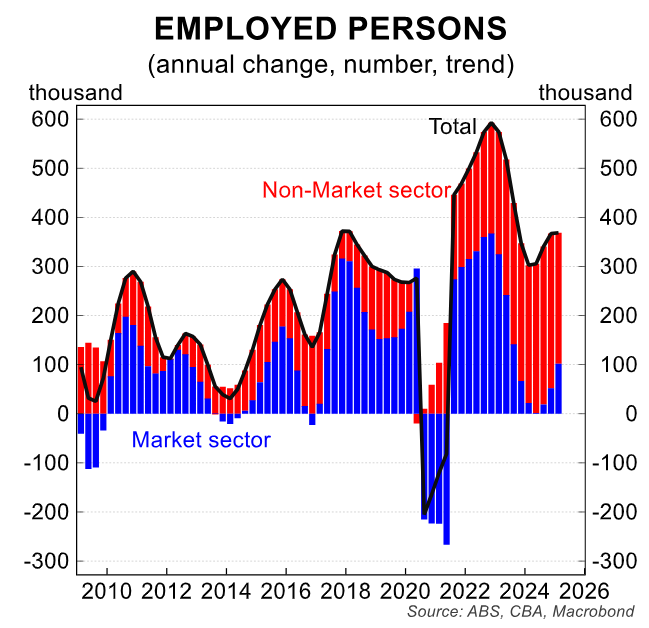

Much of this public spending has been channelled into low-productivity, non-market (government-aligned) jobs, which have expanded at a furious pace and crowded out the market sector.

Labour productivity growth in the non-market sector is deplorable, tracking around the same level as 20 years ago.

As a result, the growing share of non-market jobs has helped to drag down the nation’s productivity.

4) Poor tax policies encouraging housing speculation over productive investment:

Australia imposes high taxes on productive efforts while under-taxing efficient sources such as land and minerals. We also provide tax incentives to speculate on residential property.

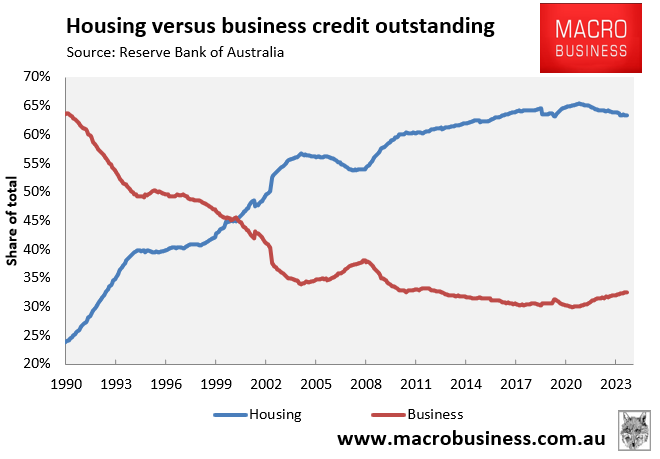

The end result is that Australia has channelled significant sums of capital into non-productive housing.

Australia has one of the most expensive housing markets in the world, with the average dwelling valued at more than $1 million.

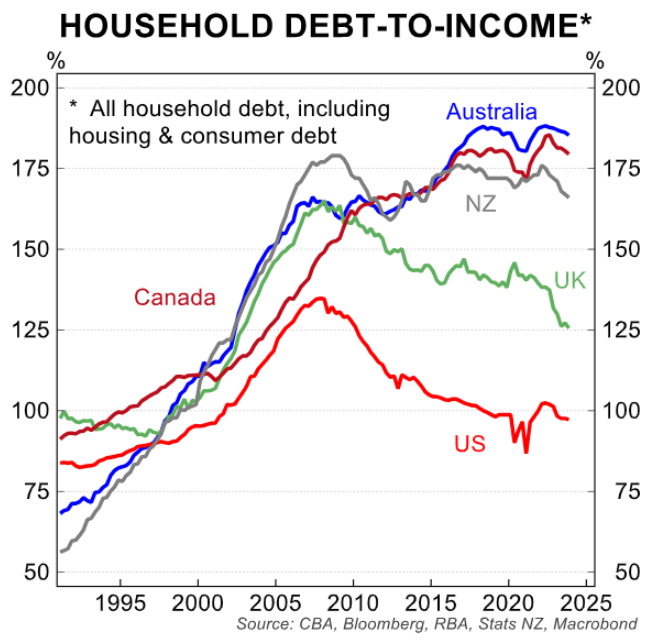

Australians also carry some of the largest debt loads in the world.

As a result, Australia has starved investment into productive businesses.

In 1990, around two-thirds of bank lending was to businesses. Now, around two-thirds of bank lending is for housing.

Why productivity growth is likely to remain sluggish:

Last month, federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers launched a productivity summit aimed at pulling the nation out of its funk that has seen per capita growth and living standards decline.

The summit is unlikely to amount to much because it won’t fix the underlying problems.

First, capital shallowing is set to continue as Australia’s population grows faster than business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

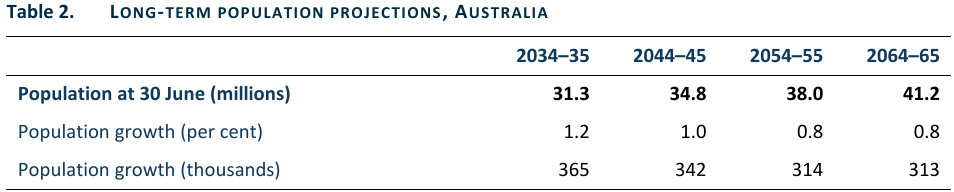

The 2024 Population Statement from Treasury’s Centre for Population projects that Australia’s population will balloon by 13.5 million people in only 40 years.

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

This 13.5 million projected population increase will be driven by permanently high net overseas migration of 235,000 annually, more than double the 90,000 average net migration in the 60 years following World War II.

This 13.5 million projected population increase is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the nation’s current population in only 40 years.

The housing, infrastructure, and business investment in these three major cities would need to be replicated in only 40 years to maintain current productivity growth, let alone increase it. That is an impossible task.

Second, the mad rush to ‘net zero’ and the failure to reserve east coast gas for domestic use will see Australian energy costs continue to rise.

The Albanese government has committed to replacing traditional baseload electricity generation with expensive and intermittent renewables.

Despite exporting nearly three-quarters of its gas, eastern Australia is scheduled to begin importing LNG by 2026 or 2027. Doing so will drive gas and electricity costs higher, deindustrialising Australia.

Finally, the Albanese government has committed to leveraging the federal budget to drive more capital into housing.

Labor has promised to effectively create a state-sponsored subprime mortgage scheme by allowing all first-time home buyers to purchase a property with a 5% down payment, with the government (taxpayers) guaranteeing 15% of the borrowers’ loan.

Labor has also stated that mortgage lenders will no longer be required to include student debts in their serviceability assessments.

As a result, the Australian economy will remain in a low productivity trap.

I discussed these issues in detail in Sunday’s Treasury of Common Sense with Mike Jeffreys at Radio 2GB/4BC.