Victorian debt explodes on bureaucratic waste

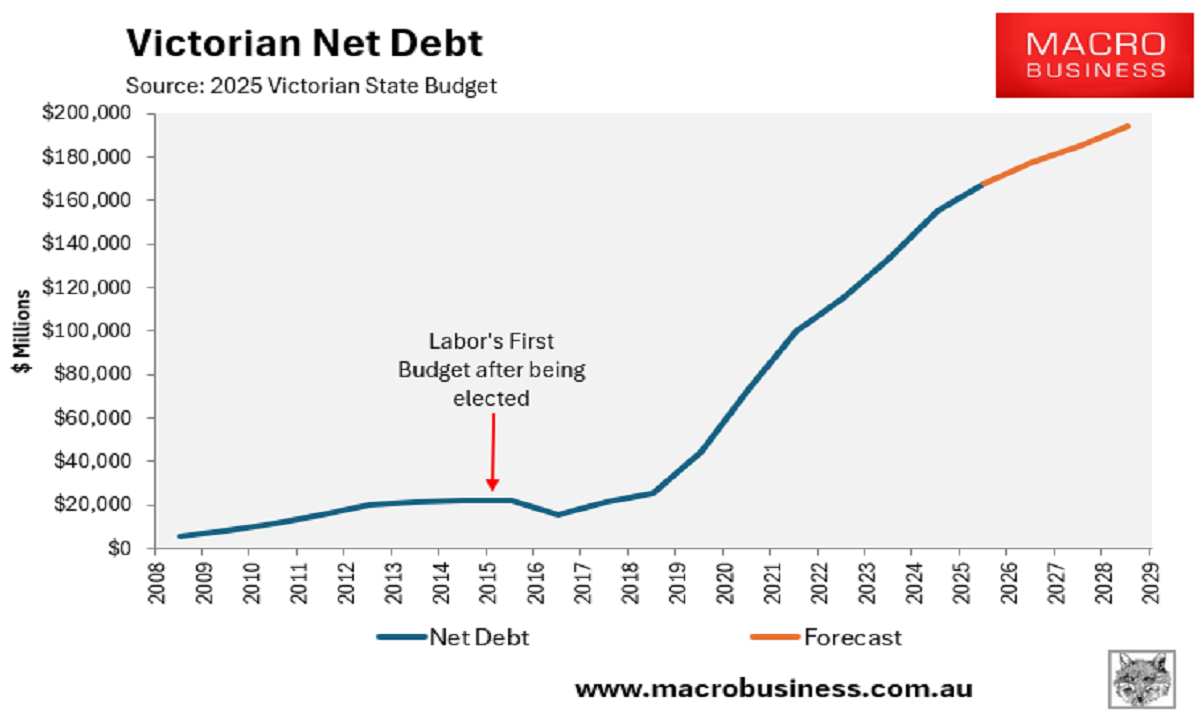

Victoria’s net debt was only $22.3 billion when the Labor government delivered its inaugural state budget in 2015. According to budget projections, it will reach $194 billion by 2028–29, up from $155.5 billion currently.

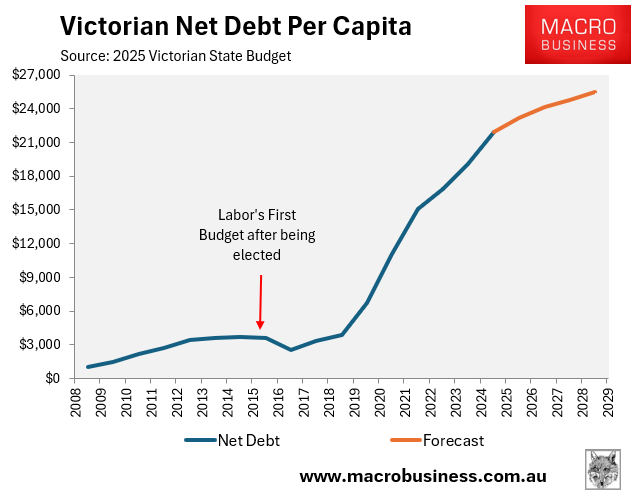

Victorian net debt per capita was less than $3,600 in Labor’s first budget. Since then, it has surged to $21,900, with projections indicating a rise to $25,500 in 2028-29.

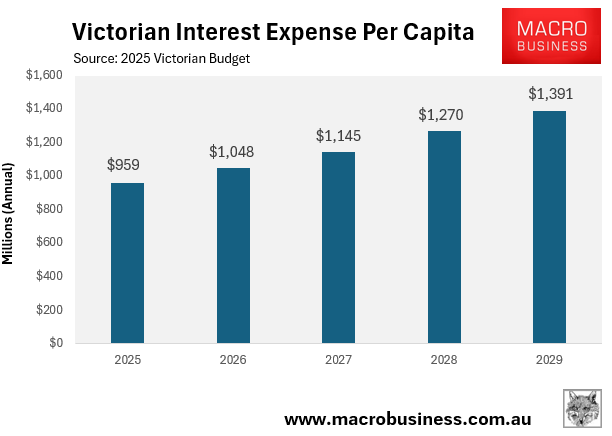

Victoria currently spends $6.8 billion in annual interest charges. By 2028-29, Victoria’s interest bill is projected to be $10.6 billion.

The projections indicate that Victoria’s annual interest expense per capita will increase from $959 in 2024-25 to $1,391 in 2028-29.

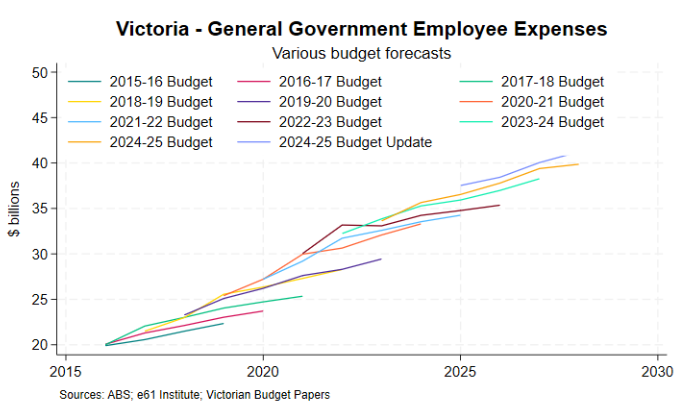

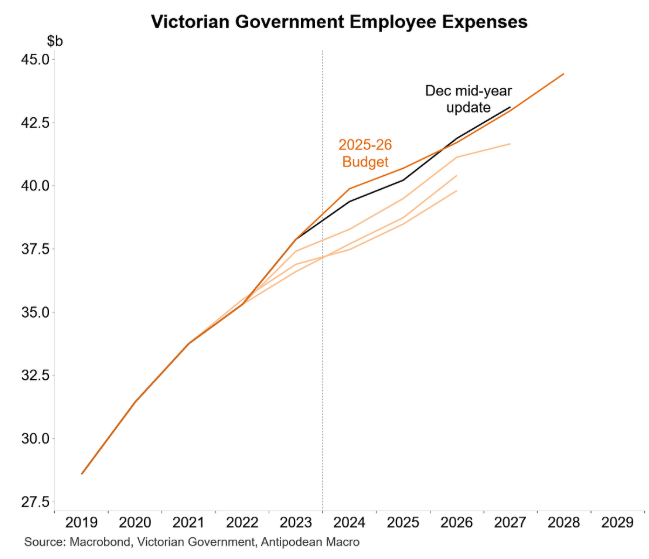

A key reason for Victoria’s dire budget situation is the massive increase in public service wages, which have consistently exceeded budget estimates.

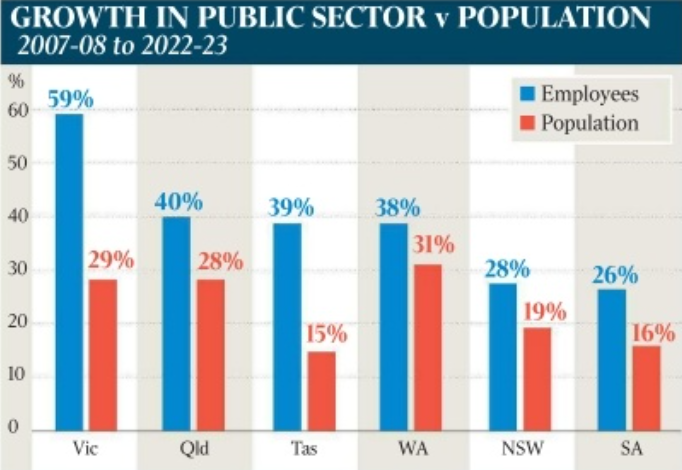

Wages are the state’s single largest expenditure. In the 15 years preceding 2022-23, Victoria’s public sector headcount increased by 59%, outpacing the state’s population growth of 29%.

Source: The Australian

Over the same 15-year period, the state’s public servant wage bill grew by 152%, outpacing all other Australian states.

Source: The Australian

Victoria’s wage bill was $19.5 billion in 2014-15. The most recent state budget projects that wage costs will reach roughly $44 billion by 2028-29.

With such a large pool of public servants, one would think that the Victorian government would not need to spend significant money on private consultants.

However, Victorian auditor-general Andrew Greaves examined the state public service’s use of external consultants and contractors, with the Allan government having spent $130 million on external contractors and consultants in 2023-24.

Greaves concluded that public servants struggle to demonstrate that their use of third-party contractors resulted in taxpayers getting value for their money.

He also called out the increased reliance on contractors and consultants, leading to a “deskilling” of the public service, and said engaging external firms often cost more than delivering the work in-house.

“DEECA, DFFH and DJCS could not always show us they actively managed the contracts we looked at”, Greaves said in the report.

“They could not always show us they regularly tracked the supplier’s progress against their budget and timeframes, such as through weekly status updates or project meetings. These departments also could not always show us that they received the product they paid for [and] used this product as intended”.

“Further, these departments could not always show us examples of work completed by their labour-hire workers,” the report said. “This means we cannot be sure these workers delivered what they were supposed to”.

The above is more evidence of why an axe needs to be taken to Victoria’s bloated bureaucracy.