Picture this. Our world. This is the world that the average Australian lives in.

They drive basic cars, they pay rates, registrations, and energy bills, they have kids at schools, and they generally spend disturbingly large chunks of their weekly incomes to service a mortgage or rent. Then they go to a grocery store and discover that tomatoes are $11.49 a kilogram and broccoli is pushing $7, and that all of a sudden everything from butter to bread, burger patties, sausages, pork chops, legs of lamb, and eggs are now inordinately more expensive than they seemed to be not so long ago.

Then these ordinary Aussies arrive home, open their mail, and discover that their electricity prices are going up, and if they do have panels on the roof, their feed-in tariff is going down. The insurance premiums on their heavily indebted homes are also experiencing double-digit growth.

The school parent payments have become progressively more insistent and larger, and if junior needs anything like orthodontics or something not covered by Medicare, the word ‘F%#k!’ often takes pole position before opprobrium sets in.

Nights with the family lend themselves more to whatever can be found on Netflix, with frozen pizzas and whatever booze is on special, telling others not to stress too much and that their wants and needs will be funded somehow.

When they do plug into the media, they find reviews of overseas locations people like them are unlikely to get to; a simply ridiculous array of recipes involving ingredients they can’t afford or time they don’t have; or an ostentatious array of eateries involving prices it makes no sense for them to consider; and a range of arts and theater events they would see for free on YouTube or online rather than get creamed to see for real.

After that, they see lots of people soaking up welfare payments of some sort or another, the odd glib throwaway piece about someone genuinely doing it tough, complete with a sad-looking photo, all interspersed with stories about how millionaire actor X met millionaire actress Z and how they clicked the first time they met, why someone from an ethnic or gender minority is offended by casual racism or sexism, why some wealthy septuagenarians are smiley and happy, and exercises people can do at their desk or without exercising too much.

There is often a panegyric about how billionaire ‘…insert name…’ is a great person and cares deeply about something, a casual warning about the incipient dangers of racism or sexism, and some reportage of sexism or racism perpetrated by someone white, toxic, and male.

Then there are opinion pieces articulating how Plebeians using energy for heating, cooling, or transport causes global warming, but also the best ski season options and beach resort picks from some island paradise somewhere.

Then it gets down to mushroom ladies, kids with machetes, and criminal gangs burning each other’s tobacco shops and the sheer grotesquerie of taxing super balances above $2 million any more than they currently are.

Sprinkled with maybe some rebuttal of the notion that increasing incomes for the poorest will endanger Australia’s competitiveness in a nation where only about 2-3% of people really have any competitive requirement at all.

You have the picture. Many of you will be living it.

That picture has just provided the backdrop to an electoral outcome seeing an incumbent government handed a very large majority after the contesting opposition leader paraded his son about as a housing battler, went nuclear on energy, and coughed up gas reservation as an idea but walked it back almost from the moment he threw the idea into the public domain.

The newly refreshed cabinet, comprising a majority of investment property owners, now sits around a table where they know the people who voted their majority are unhappy about housing and costs of living in general, and they have promised to do something about it.

Their starting position in May 2025 is some of the world’s most expensive housing, occupied by some of the world’s most indebted people, using some of the world’s most expensive electricity and internet, working in some of the world’s most expensive office, retail, or factory space, with all of these making them some of the world’s most expensive people.

Unsurprisingly, those people are to a very large degree either directly employed by the government, or employed by some entity directly contracted to the government, or leveraging a policy position enacted by the government.

With the exception of about 2-3% of people directly connected with commodity or agricultural exports, they are employed or living in a bubble largely funded by the government taxing them, supplemented by what it rakes off those commodity exports.

Those people, their lives, and their families are, to a considerable degree, ‘uneconomic’ from the point of view of the rest of the world. The only people for whom those lives are not ‘uneconomic’ are those benefitting from the policy balance between who is taxed and why, and who is remunerated what and why, with the accompanying who can claim what tax concession and why providing a backdrop.

At that point, consider a piece lobbed in by the ABC’s Patricia Karvelas on Saturday, entitled Housing Minister Clare O’Neil takes aim at Australia’s regulation red tape.

Ask yourself if the sentiments expressed reflect your understanding of the drivers of Australia’s economic issues and if the responses have any credibility whatsoever from the world in which most of you live. Bear in mind that Patricia is a very good journalist, and consider that if very good journalists can’t go closer to the lived substance of a story on the national broadcaster, then the prospect is that the nation is bullshitting itself.

Let us look at the farce.

She knows that if Labor isn’t able to deliver on its housing promises, a generation of Australians will not only feel let down, they will have a right to feel angry that the system is stacked against them.

Wrong. Australians will not have a right to feel let down ‘if’ the ALP isn’t able to do something; Australians already feel let down by a political economy that has repeatedly failed to address rising house prices since the early 1990s. Very large numbers of them already feel angry that the system is stacked against them and has been for a generation.

Very large numbers of them already feel hostility to the possibility that their lived experience – their remunerations, their job options and prospects, the commute to their workplace, their rates of taxation, and the support they can access from any form of government – is stacked against them and has been for a very long time.

Then,

Anger about housing wasn’t a manufactured crisis at the last election — it was real and visceral but ultimately the opposition was never able to turn that anger into votes, particularly among younger voters where feelings on this are so intense.

Yep, that anger has mounted for the best part of 30 years, as housing affordability passed beyond the reach of the younger and less affluent, and nobody in Australian politics has seen fit to address the issue. Over thirty years, Australians have progressed from a PM baldly stating that nobody complains about the value of their house rising, via a slalom line of first-homeowner grants and enticements, past a chorus of enticements for housing speculation for the more affluent or older, while meaningful employment was increasingly offshored, taxation consolidated on the less affluent, and government supports nailed to the floor and made less accessible. Is anyone that surprised?

From there we move to:

“It’s just too hard to build a house in this country,” O’Neil says.

“And it’s become uneconomic to build the kind of housing that our country needs most: affordable housing, especially for first home buyers.”

O’Neil says the housing crisis is, in part, the result of “40 years of unceasing new regulation” across three levels of government.

“On their own, each piece makes sense. But when you put it together, builders face a ridiculous thicket of red tape that is preventing them building the homes we need. And if we’re going to tackle the fundamental problem — that Australia needs to build more homes, more quickly — we need to make a change.”

A piece of news for the Minister and the journalist is that it is currently ‘uneconomic’ to do just about anything in this country. Would anybody in their right mind invest in anything in Australia competing for a product or service market from somewhere else? Would anybody in their right mind invest anything in providing a product or service inside Australia’s economic bubble and have confidence that a polity (ALP, Liberals, Nationals, Greens, and sundry nuttercrats) will cover the macro while the business is economic inside the bubble? The same polity that has made such an epic miasma of, inter alia, housing, immigration, free trade, manufacturing, housing investment, taxation, superannuation, education, media, Covid, etc?

Then after cogitating on that for a second, ask yourself if Australia has addressed that regulation by building more houses per capita than any other country in the OECD with the second largest housing construction sector in the OECD. Is the construction and regulation the issue or is the demand the issue? When the Minister asserts:

“And, tackling our drive towards building 1.2 million homes around the country by focusing on stagnant construction productivity.”

Is it worth asking just how stagnant it is if we have built more houses and have a larger housing construction sector than almost anyone else? Is our Minister babbling bullshit?

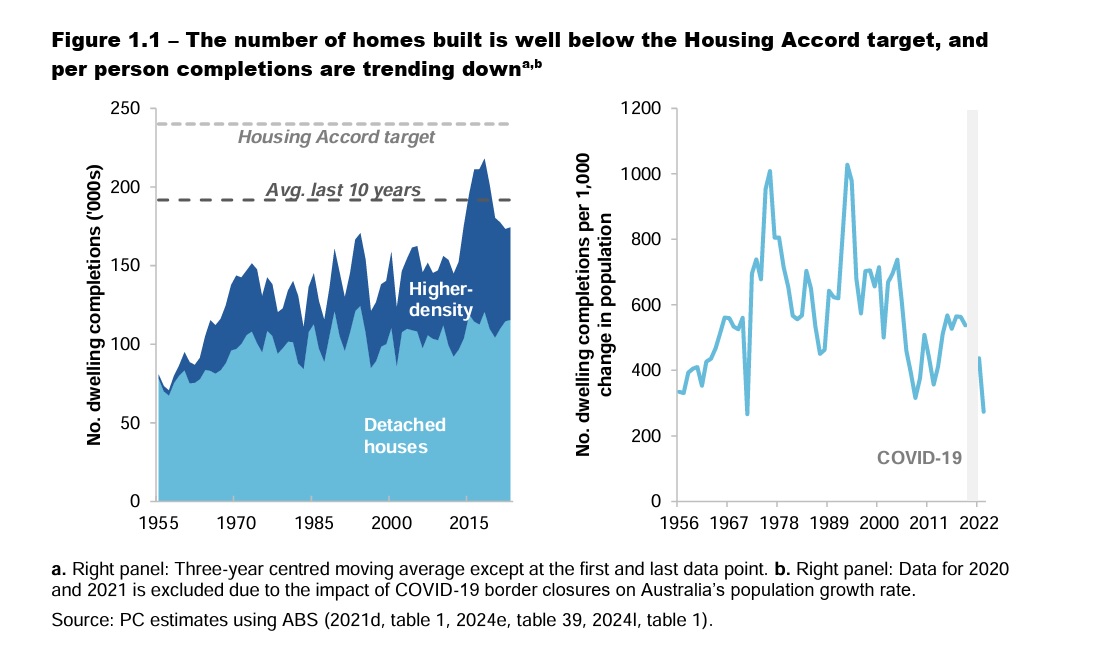

The Productivity Commission report from January this year goes to the nub of that stagnation with one pair of telling charts.

The chart on the left tells us that the construction of detached housing has been about 100 thousand per year since the 1970s, and that the ‘Housing Accord’ introduced by the 2022 Albanese government has a ‘target’ that stretches credulity at about 250 thousand detached and higher-density abodes, a point more than 10% above the very highest peak of Australian construction in 2017.

It is important to remember that Australians appear to have reservations about higher-density housing as well.

The chart on the right tells us that, per head of population in the country, the number of housing completions has peaked twice, in the late 1970s and the late 1990s, and is now at multi-generational lows.

At a global level, Australian housing construction productivity looks just fine. The next two charts from the same report bring about the question, ‘what planet are our politicians and bureaucrats on?’

That chart on the left tells you that Australian housing construction types have done ten tonne steamers on just about everyone else in the developed world since 1994-95, although that one on the right tells you that Australian building completions – bearing in mind that Australians are currently living in some of the world’s biggest abodes – are on the expensive side.

Beyond that the Productivity Commission report baldly states:

Poor construction productivity growth is not just an Australian phenomenon. Indeed, Australian aggregate construction (including residential, commercial and civil) labour productivity growth is at least on par with overseas peers (though there are measurement challenges).

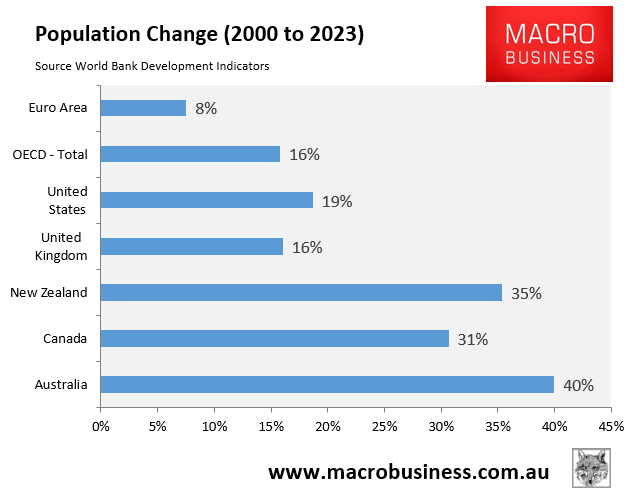

Therefore, this is not solely an Australian issue, regardless of what the productivity problem may be. Australia is already building more houses (and apartments) and dealing with the same productivity issues as the rest of the world. As Leith and David point out ad infinitum, Australia doesn’t have a housing productivity problem, it doesn’t have a housing supply problem, it has a housing demand problem into which it has poured a million new bums on seats in 3 years.

Given that Australian population growth is driven almost solely by immigration – seeing as all potential mums and dads are too busy working their backsides off to pay rent or a mortgage and come home far too shagged out to practice their twerking or twin-backed beast dynamics with a significant other – Australian housing has an immigration problem.

We should thank the Productivity Commission for their honesty. Those charts tell us that housing costs will not be going away any time soon, and that any politically inspired ‘Housing Accord’ style ‘target’ is likely to have some bullshit baked in.

The Karvelas piece does do us justice in reminding us that the Liberals, who held power for 10 years prior to ScoMo seeing them out the door, have no answers for the issue either. Neither side of Australian politics offers any real solutions for the world in which most Australians live. That is why Australians living in that world are increasingly interested in fewer people joining us as Australians.

It isn’t that we dislike foreigners; in fact, an OECD-leading 30% of Australians are born outside the country.

It is that we wonder about the logic of promoting that many people to come and join us if all we are doing is making them ‘uneconomic’ the moment they get off the plane, and all they are really doing is queuing up alongside us to buy exorbitantly priced groceries, or to pack into our train or bus rides, or join us on the roads, or, in desperation, to outbid us as housing buyers and renters. All in an economy reliant on about 2-3% of the population to provide our economic substance, with the rest of us living in an economic bubble.

And at that point, we await the next moves on energy, super, tax, education, etc.

Keep your credulity expectations in check.