Wind power has become a significant contributor to the electricity supply in Australia.

As of September 2024, Australia had an installed wind capacity of around 13.3 GW. Wind power accounted for 13.4% (or 31.9 TWh) of Australia’s total electricity production in 2024.

The Albanese government has set a target of producing 82% of Australia’s electricity sources by 2030.

Some of Australia’s states have gone even further. South Australia has set a 100% renewable energy target by 2027, whereas Victoria aims to deliver 95% renewable energy by 2035.

There is a significant issue with these plans: renewables are weather-dependent and intermittent, rendering them unreliable.

I reported last week how South Australia’s renewable energy production collapsed during a prolonged ‘wind drought’.

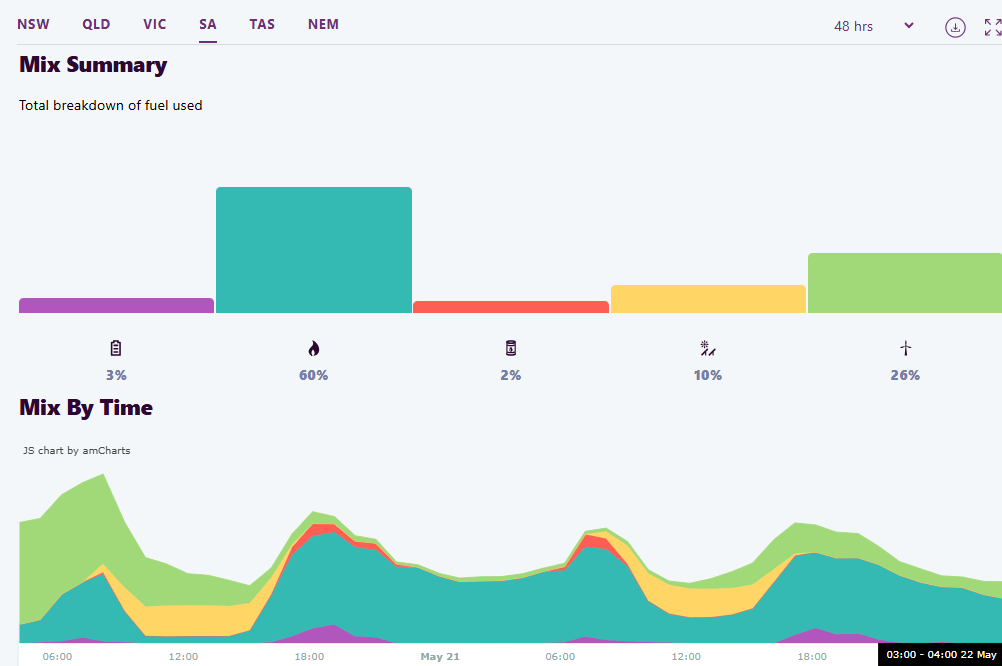

South Australia’s electricity generation (21-22 May 2025)

As a result, over a 48 hour period between May 21 and May 22, 60% of South Australia’s energy came from gas and 2% from dirty diesel.

To add insult to injury, South Australia imported brown coal-generated electricity from Victoria, which also experienced a wind drought.

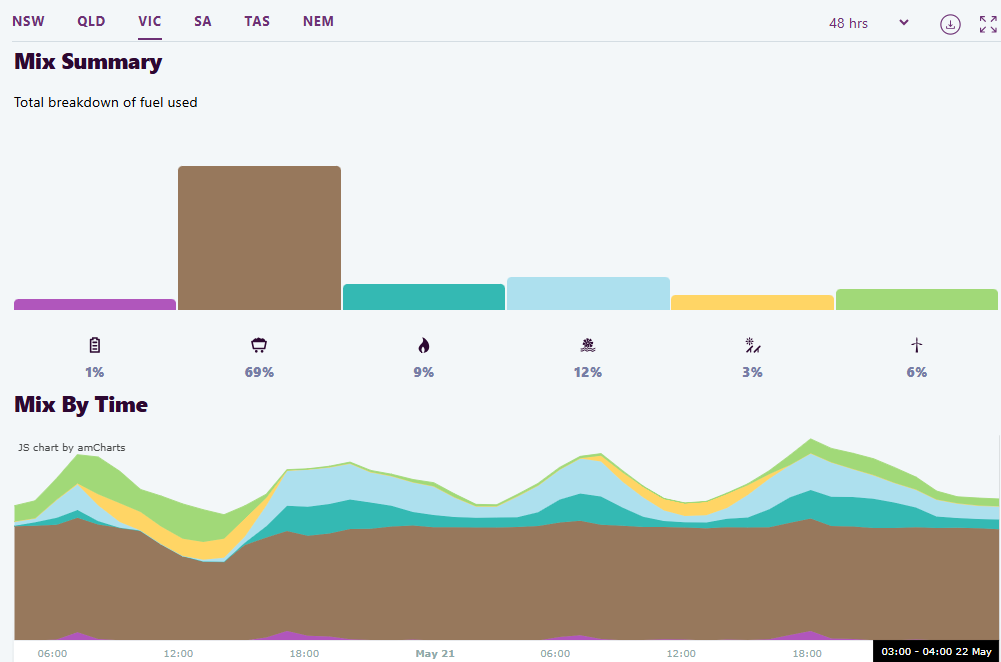

Victoria’s electricity generation (21-22 May 2025)

The weekend saw ‘wind drought’ conditions hit much of Australia, rendering renewable power generation useless.

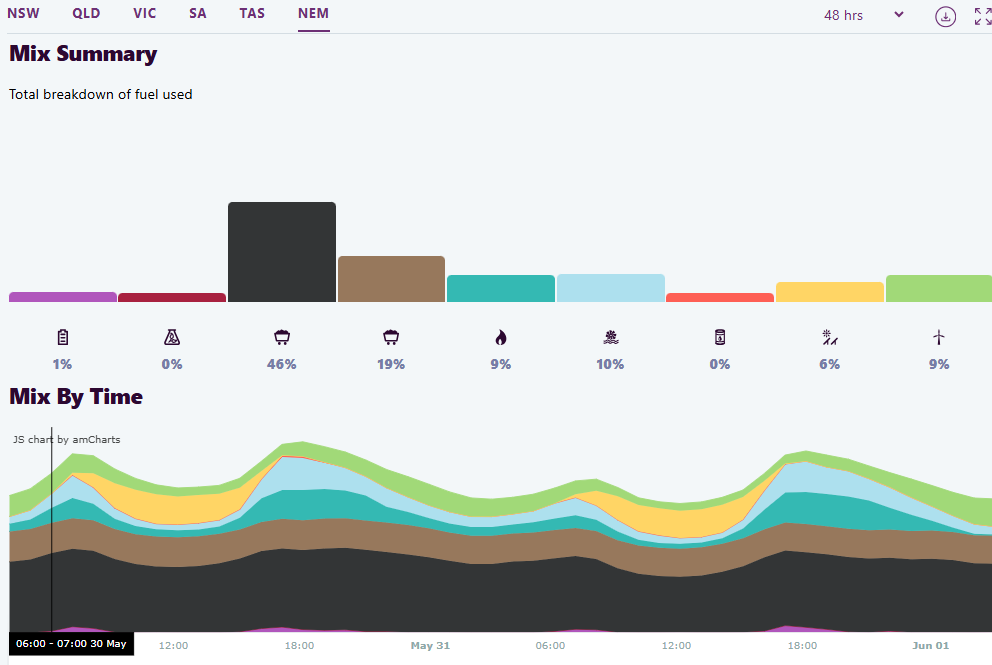

Over the 48 hours to 1 June, wind produced only 9% of Australia’s needs, solar 6%, and hydro 10%. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Australia’s electricity generation came from fossil fuels: coal (65%) and gas (9%):

NEM electricity generation (31 May to 1 June 2025)

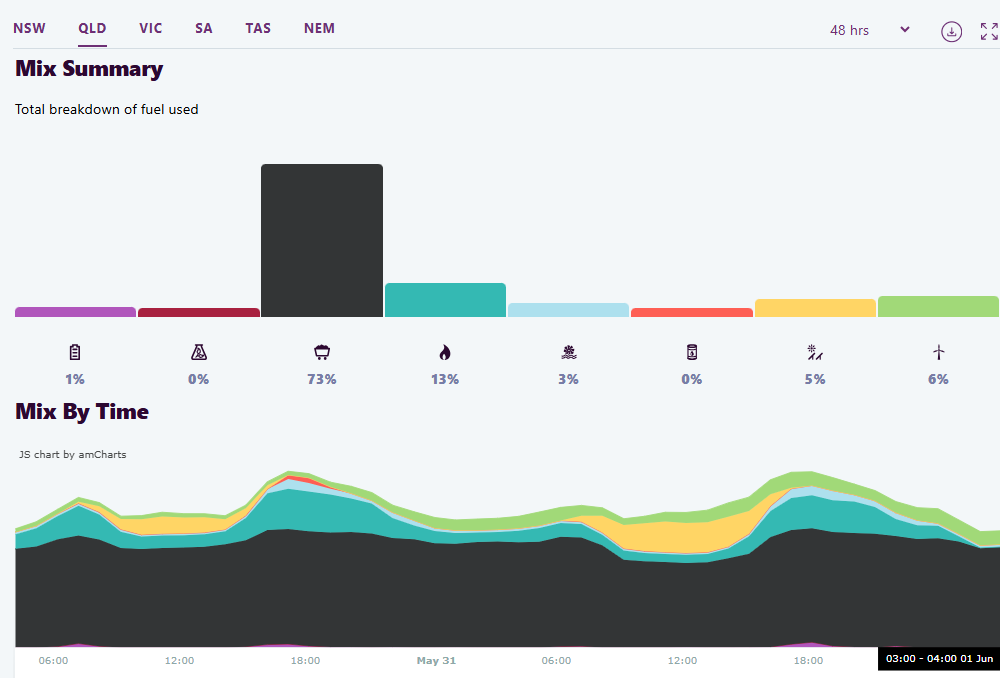

Queensland was hard hit by wet weather and still conditions, producing a whopping 86% of its power from fossil fuels: coal (73%) and gas (13%).

Queensland electricity generation (31 May to 1 June 2025)

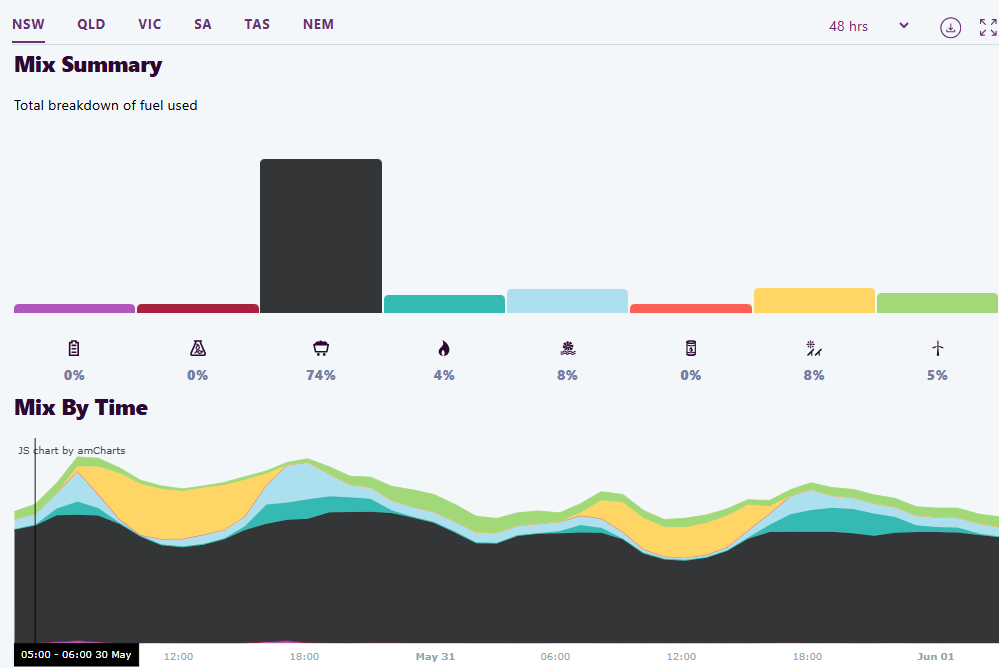

NSW was also hit by the “wind drought”, producing 78% of its electricity over 48 hours from fossil fuels: coal (74%) and gas (4%):

NSW electricity generation (31 May to 1 June 2025)

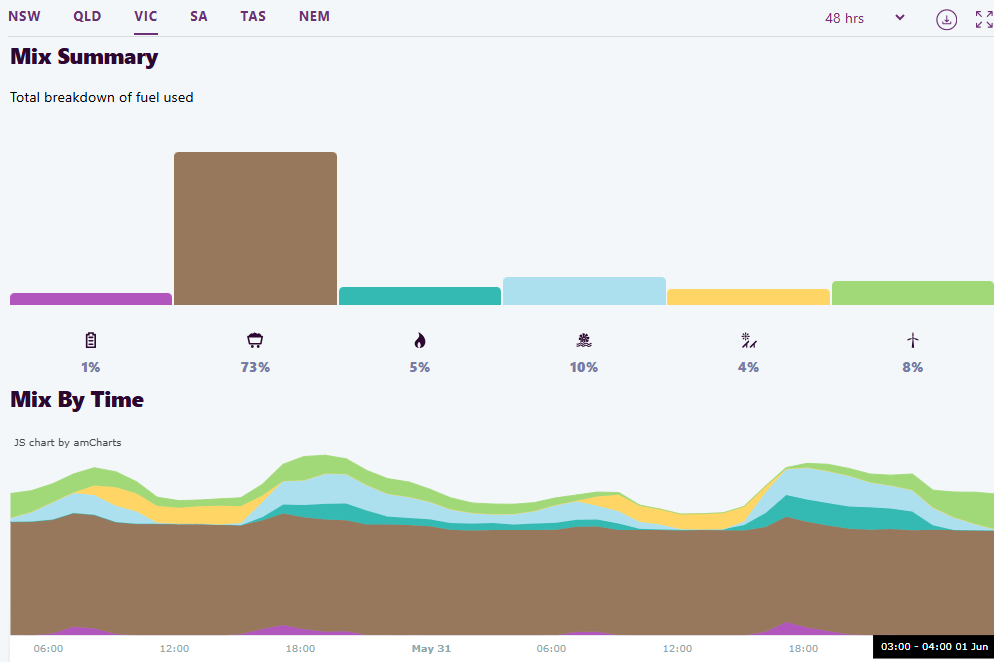

So too was Victoria, which generated 78% of its energy from fossil fuels over the 48 hour period: coal (73%) and gas (5%).

VIC electricity generation (31 May to 1 June 2025)

Wind droughts are especially common in winter, which is also when solar generation is severely hampered by cloudy conditions and shorter days.

The obvious question follows: How can Australia realistically hope to substitute reliable baseload power generation with weather-dependent and intermittent renewables? And how much will it cost?

Because renewables are unpredictable and intermittent, Australia would need to build masses of extra capacity, redundancy, and storage to ensure that there is always enough supply to meet demand. The costs will be enormous, driving up retail power bills and taxes (via subsidies).

Consider the following single example. The Millmerran coal-fired power station near Toowoomba, Queensland, was commissioned in 2002 and cost $1.5 billion to construct. It is located some 130 kilometres from Brisbane, has an 850 MW capacity, and can operate almost 24-7 if required.

The typical wind turbine currently operating in Australia generates 3 MW. However, the newest models under construction can generate about 6 MW, so I will be generous and use this higher figure.

To replace the Millmerran coal-fired power station with wind power would require around 140 turbines (850 divided by 6) just to get the nameplate. However, wind power has a capacity factor of around 30%, meaning that we would need more than 450 wind turbines to get the average electricity output of Millmerran. We would also need loads of pumped hydro or battery storage to store excess power for use during wind droughts.

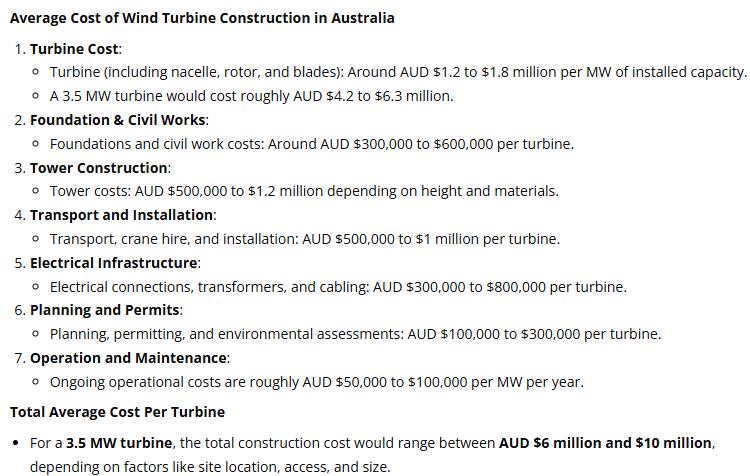

The cost of these 450-plus wind turbines would be enormous. The purchase and installation cost of a wind turbine typically ranges from $6 million to $10 million for a 3.5 MW turbine:

The costs would be higher for the newer and larger 6 MW turbines.

Additionally, there are costs for the transmission needed to connect the turbines to the grid, as well as for constructing service roads to access each turbine.

Unlike Millmerran power plant, which is located only around 130 kilometres from Brisbane and is connected with one set of transmission lines, the wind turbines would require a spiderweb of transmission and would be located further away, increasing the costs.

Then add the costs associated with storing the wind power (i.e., pumped hydro or batteries) so that it is available on demand, not only when the wind decides to blow.

Just from the example above, you can see how the transition to a renewable energy future will cost a fortune and will result in a less reliable energy system. Energy bills will rise, taxes will increase (to pay for subsidies), and blackouts will become increasingly common.

The environmental costs associated with land clearing to accommodate wind turbines (e.g., the construction of service roads and tree clearing) should also be factored in, as should the thousands of tonnes of concrete and reinforced steel required for the foundations. The sheer environmental footprint of wind power is enormous.

Interestingly, The AFR reported over the weekend that Victorian energy users face a 50% increase in electricity bills to pay for the rollout of transmission lines to support the state’s 95% renewable energy target:

The total cost to households and businesses for the upgrade to Victoria’s electricity grid, required to support the shift to renewable energy, will be more than four times the $4.3 billion figure set out in a transition road map unveiled last month.

Experts say the bill for building the network of poles and wires is likely to be more than $20 billion…

“This is a bit over five times the total regulated value of Victoria’s existing transmission network”, [Professor Bruce Mountain, the director of the Victoria Energy Policy Centre said].

The cost of building and maintaining poles and wires are recouped via consumer energy bills, which Mountain said would rise by about 50% or more under the plan.

Weather-dependent energy is inherently unreliable energy. It is also incredibly expensive due to the massive transmission and storage needed and the requirement to keep fossil fuel generators on standby when wind and solar generation collapses.

Policymakers should stop obfuscating and be upfront about the costs and trade-offs in Australia’s renewable energy transition.

I discussed these issues with Gary Hardgrave at Brisbane Radio 4BC last week.