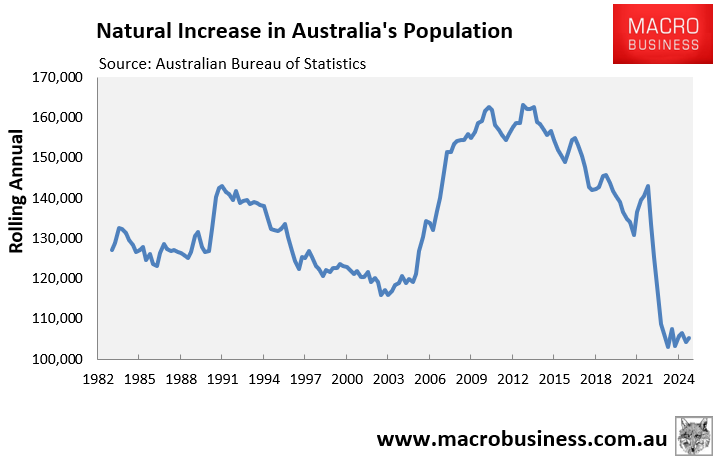

Thursday’s Q4 2024 population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) revealed that “natural increase” (i.e., the number of births minus deaths) fell to only 105,200 in 2024, close to the lowest level on record.

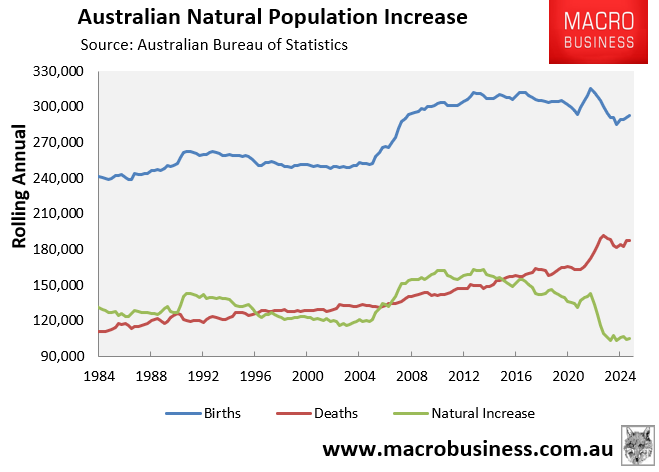

There were 292,500 births in 2024, offset by 187,300 deaths, the latter of which have risen following the Covid-19 pandemic and the gradual expiry of the large baby boomer cohort.

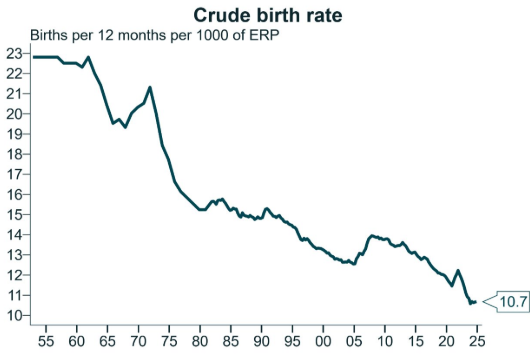

As illustrated in the following chart from Alex Joiner at IFM Investors, Australia’s crude birth rate—i.e., annual births per 1000 resident population—has plunged to 10.7, the lowest level in recorded history:

Source: Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

As you can see, Australia’s birthrate has trended lower for 70 years and is currently tracking at less than half the level of the ‘baby boom’ in the 1950s and early 1960s.

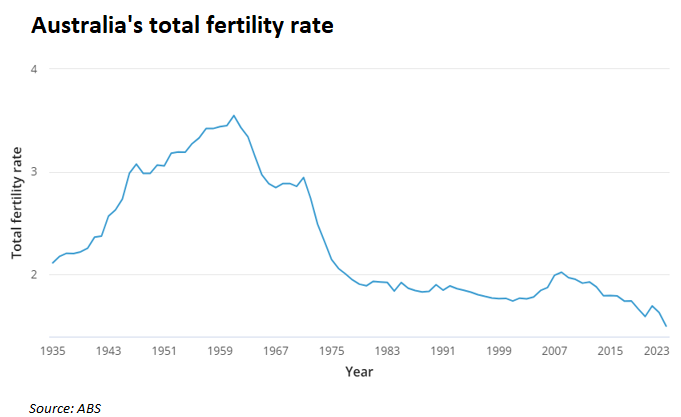

The latest official fertility rate from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) hit an all-time low of 1.50 in 2023.

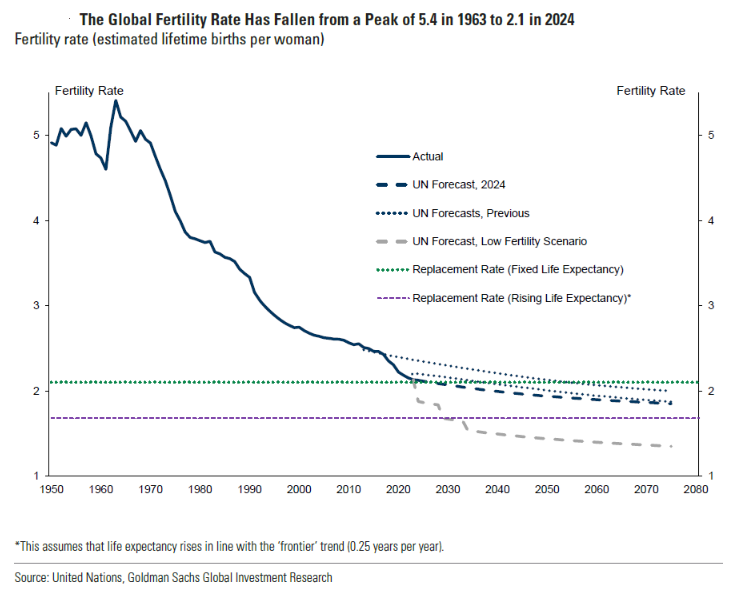

Falling fertility rates are a global phenomenon, having fallen from a peak of 5.4 in 1963 to 2.1 currently.

The developed market rate has fallen from 1.9 to 1.5 since 1975.

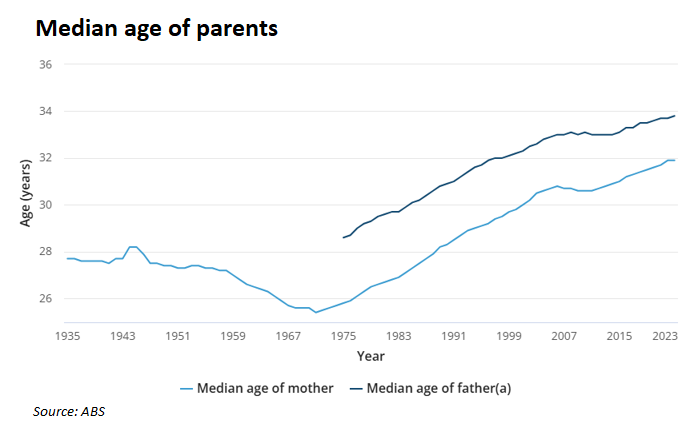

According to the ABS, the median age of parents in Australia also hit a record high of 33.8 (fathers) and 31.9 (mothers) in 2023.

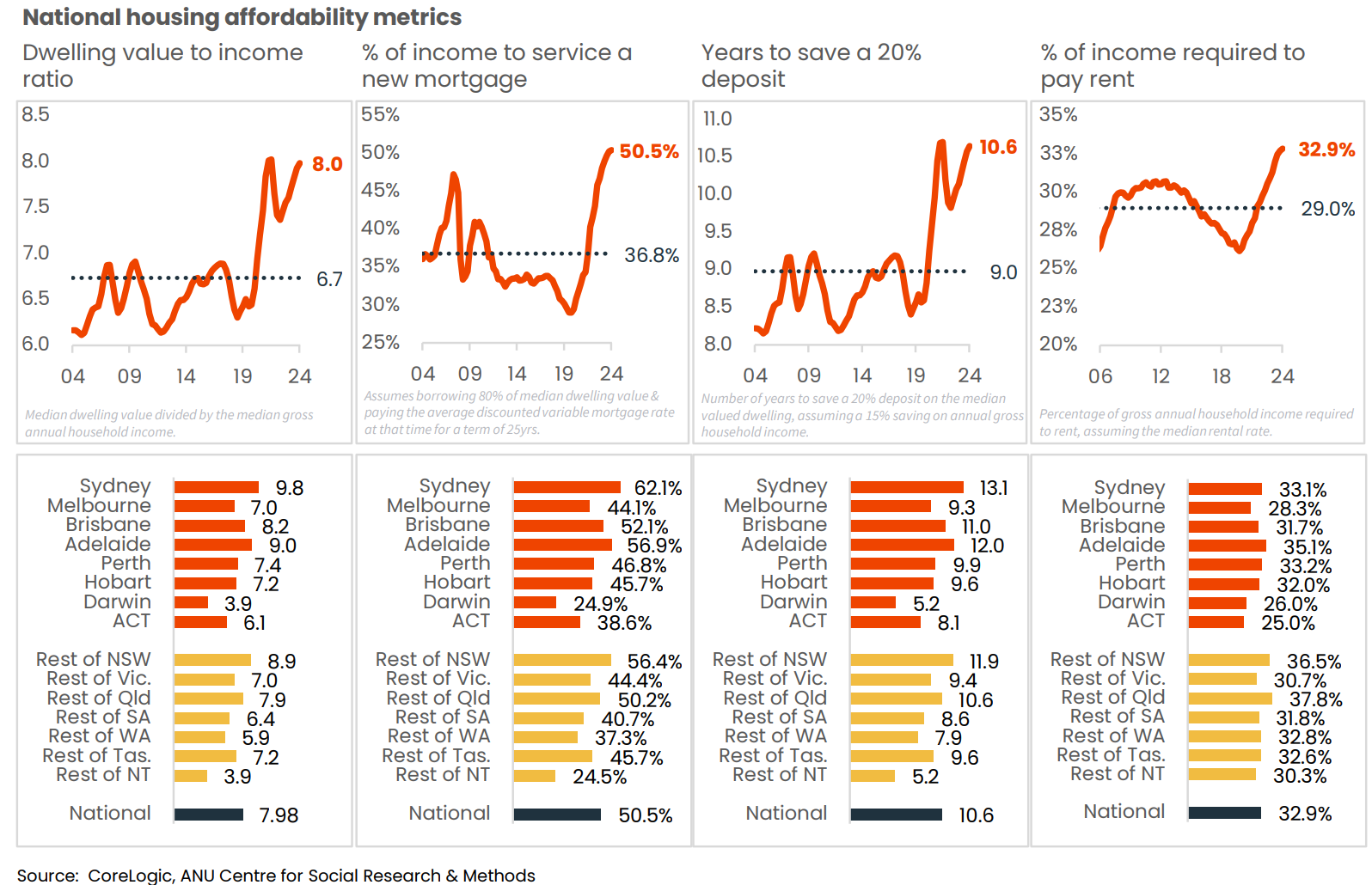

Rising housing costs must undoubtedly be a barrier to couples starting families, though it is not the only one.

As illustrated below by CoreLogic (now Cotality), the cost of purchasing and servicing the mortgage on a home hit a record high at the end of 2024, alongside the cost of renting.

Research from HSBC shows that “a 10% increase in house prices leads to a 1.3% drop in birth rates, and an even sharper fall among renters”.

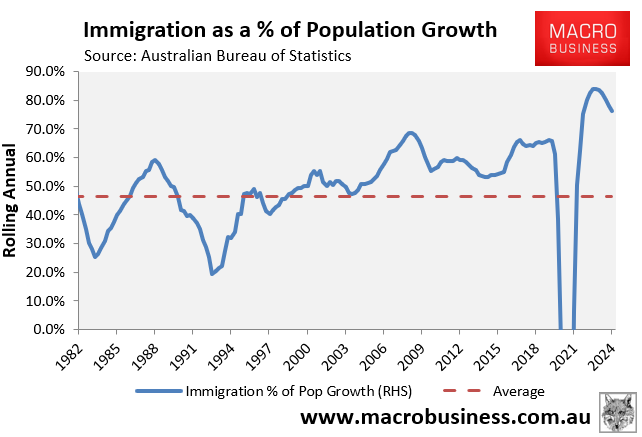

Historically high immigration is a key driver of Australia’s rising home values and rents. Therefore, it too is contributing to the nation’s falling birth rates.

Australia’s immigration policy has created a negative feedback loop. High rates of migration combined with low availability of housing has driven up home prices and rents. This, in turn, has helped to lower the fertility rate, which, in turn, has resulted in the government backfilling population growth via immigration policy.

As a result, net overseas migration comprises a historically high share of Australia’s population growth.

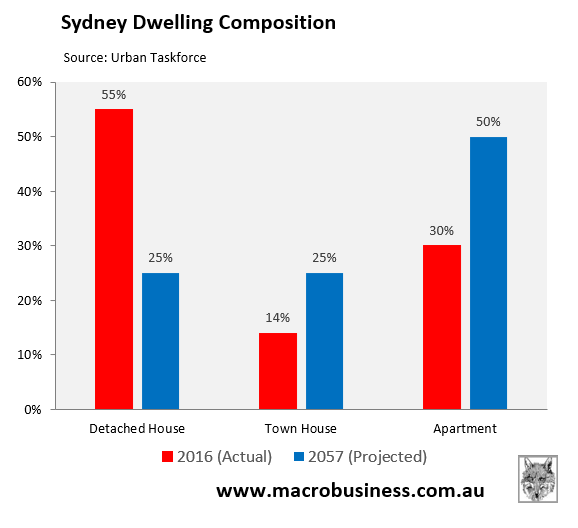

Immigration-driven population expansion has also changed (and will continue to change) the makeup of housing in our major cities, from family-friendly houses with backyards to family-unfriendly one- and two-bedroom high-rise apartments.

Simply put, Australia’s immigration and housing policies discourage couples from having children. They have become too expensive and are now considered a luxury.