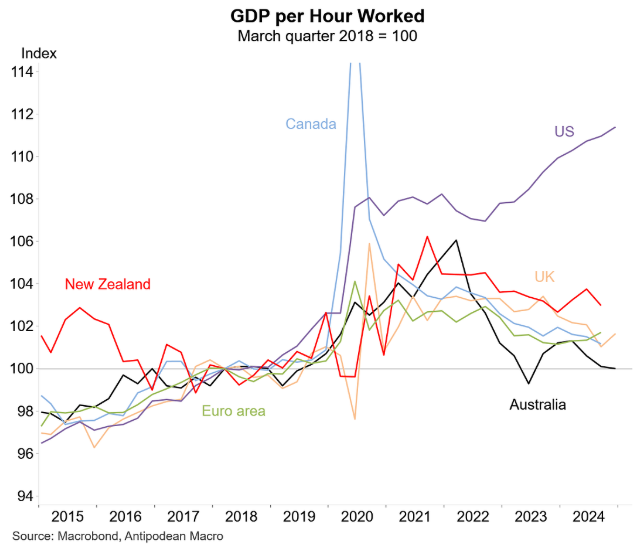

Australia’s recent productivity growth has been among the worst in the advanced world, as illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro.

This month, federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers launched a productivity summit aimed at pulling the nation out of its funk that has seen per capita growth and living standards decline.

The Guardian’s economics editor, Patrick Commins, is already looking at ways that Australia could ‘spend’ the bounty from productivity gains, assuming they arrive:

If we are successful in lifting productivity, what should we do with the dividends of our success? Or more simply: do we want to work less and spend the same, or do we want to work more and spend more?

Looking at history, the answer has been a combination of the two, according to Rusha Das, a research economist at the Productivity Commission.

In a new paper, Das calculated that Australians used only 23% of the productivity “dividend” from the past 40-plus years to work less, while we banked the remaining 77% as higher income.

“Rather than spending our productivity dividend on more spare time, we have largely traded it for higher incomes, and more and better stuff,” Das said.

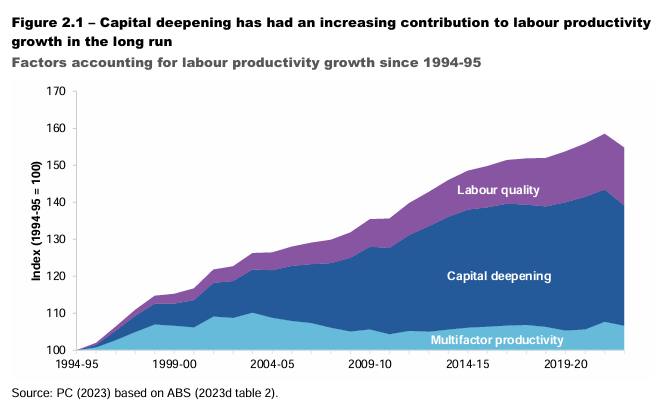

The Productivity Commission’s (PC) recent report, entitled “Productivity before and after COVID-19”, identified capital deepening (i.e., an increase in the capital-to-labour ratio) as the main driver of productivity improvement:

More capital (the machines, equipment and other durable goods that are used as inputs in production) helps workers to produce more goods and services. For example, a baker is much more productive if they have an oven, utensils, and an automatic mixer to help them bake bread. Construction workers are more productive if they dig with shovels, rather than spoons.

All else being equal, an increase in the capital-to-labour ratio (known as capital deepening) enables workers to produce more output per hour – and has been a key driver of increases to labour productivity over the past 25 years (figure 2.1).

The PC also warned that “if this low rate of investment persists, it may contribute to a longer-term productivity slowdown in Australia”.

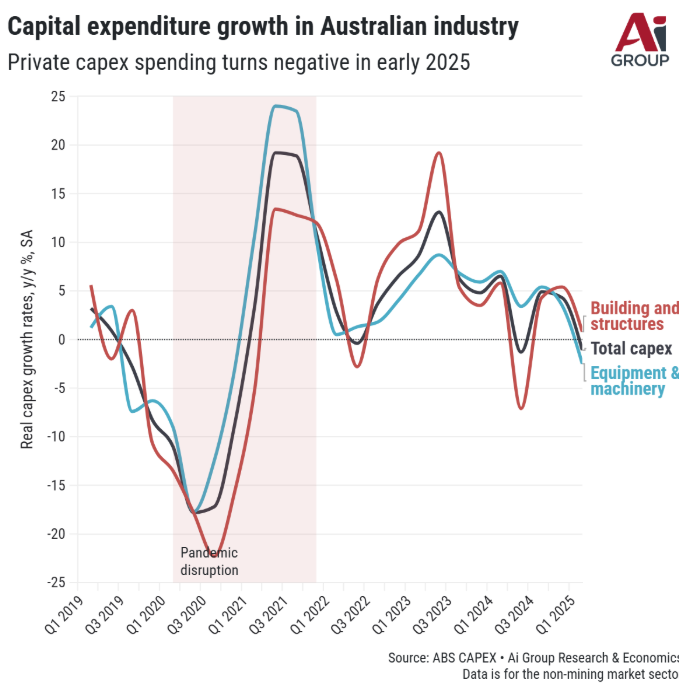

Former long-time Treasury Secretary Ken Henry recently explained that the slump in Australia’s productivity has been caused by a decline in the capital-to-labour ratio, or “capital shallowing”.

[Capital deepening] makes each hour worked more productive, right?.. And capital deepening is obviously driven by having a rate of national investment that is matched to the rate of workforce growth, obviously, right? And so if your rate of workforce growth stays constant and your level of investment plummets, you’re going to suffer capital shallowing eventually.

And by the way, that is what Australia has suffered in the last 10 years, capital shallowing. It’s an extraordinary thing, capital shallowing, and it’s a consequence simply of the collapse in the investment rate.

You experience capital deepening when the investment rate is sufficiently high relative to the rate of workforce growth, right? And that’s what Australia has experienced for most of the post-war, I mean post-World War II period, is capital deepening.

The latest ABS capex survey showed that private investment has collapsed, driven by equipment and machinery:

As a result, capital shallowing is likely to persist in the near term, which will continue to drag on productivity growth, per capita GDP, and living standards.

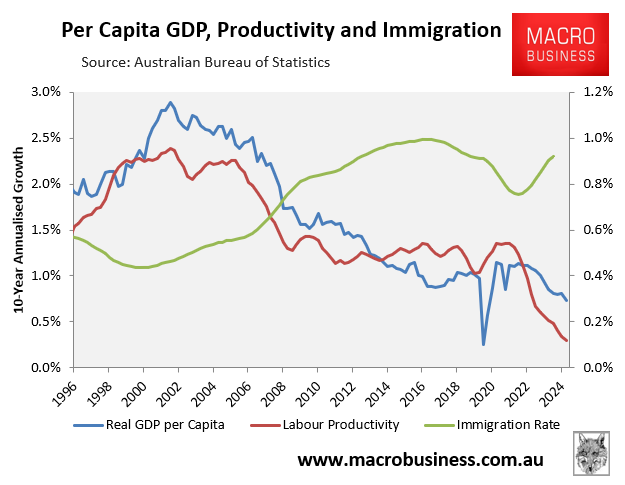

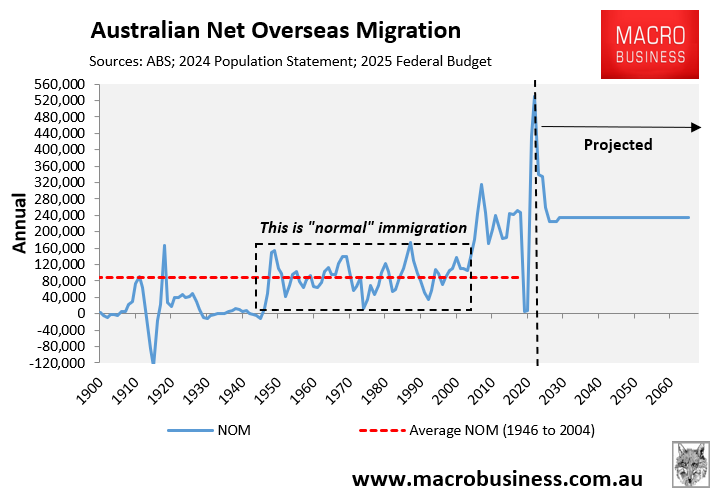

The long-term outlook for capital deepening and productivity is also poor because the federal government remains intent on growing the population aggressively via net overseas migration.

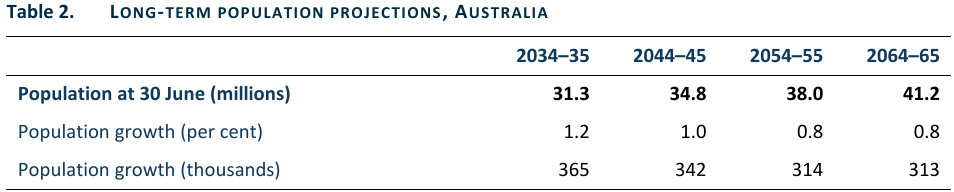

The 2024 Population Statement from the Centre for Population projected that Australia’s population will swell by 13.5 million in only 40 years, which is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the current population:

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

This 13.5 million projected population expansion will be driven by a permanently high net overseas migration of 235,000 annually, which is 160% higher than the 90,000 average net migration in the 60 years following World War II.

All of the housing, infrastructure, and business investment in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane would need to be replicated in only 40 years to maintain the current capital-to-labour ratio, let alone increase it. That is an impossible task.

In other words, growing the population this aggressively will ensure that the denominator of the capital-to-labour ratio will increase, lowering the ratio.

Business and infrastructure investment will forever fail to keep pace with population growth, lowering potential per capita GDP growth and living standards.