Policy makers and economists are concerned that the retirement of the Baby Boomer generation and an ageing population could see the nation’s workforce heavily diminished in the future.

For example, Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers warned in January 2023, just as immigration was ramping to record levels, that longer life expectancy and a sharp decline in Australia’s fertility rate meant that Australians would pay higher taxes to fund government services and the aged care sector.

Among other things, Chalmers touted changes to Australia’s immigration system to address population ageing:

“It’s becoming more important than ever to build a bigger and better-trained workforce, particularly with the proportion of working age people projected to decline in the years ahead,” Dr Chalmers said…

He highlighted the need to make it easier for parents to work more, to get more people into skills training, and improving the migration program, which is the focus of the migration review being led by Clare O’Neil.

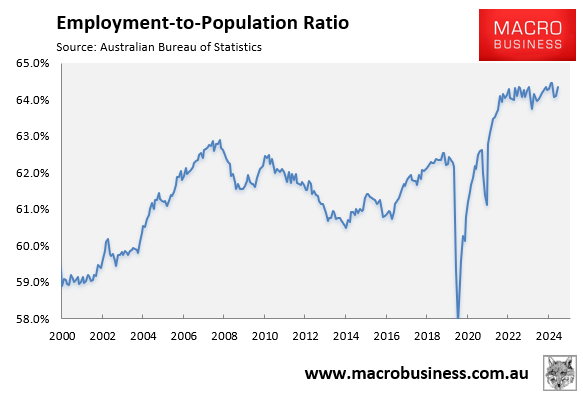

The fact is that Australia’s population has been ageing for decades. Australia also had negative net overseas migration (NOM) throughout the pandemic. Nonetheless, the proportion of Australians in paid employment has been at record highs since the middle of 2022:

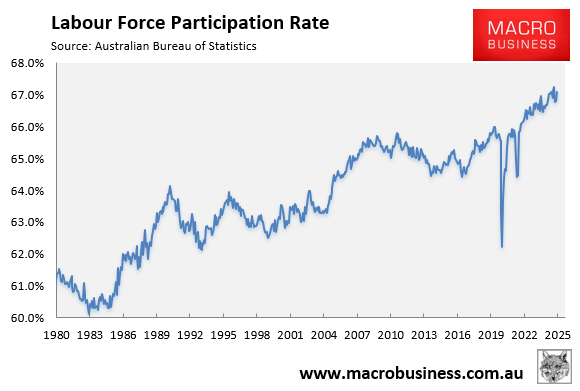

Australia’s labour force participation rate has also risen for decades to its current record high level:

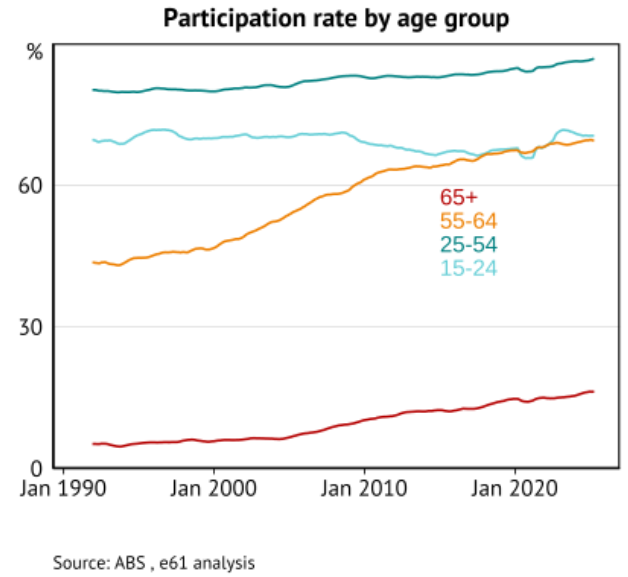

New analysis from the e61 Institute shows that “an ageing population is not necessarily having a negative effect on the labour market”.

e61 shows that the participation rate of older workers is on the rise relative to younger workers:

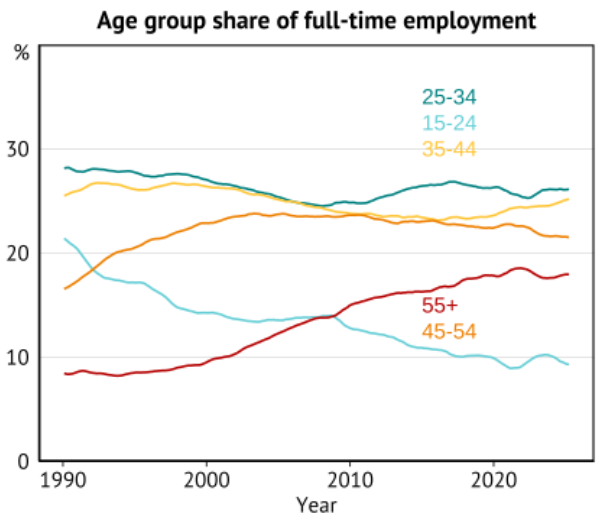

Moreover, while the share of older workers in full-time jobs continues to fall—partly because of the expansion of employment for this group—e61 shows that their share of total full-time employment is actually increasing:

“Overall, current fears about the adverse impacts of ageing on the labour market may be overstated”, e61 concludes. “While the impact of the ageing population on the labour market is still unfolding, these trends highlight the importance of health policy in shaping long-term labour market trends as the population becomes more vulnerable to ill-health and frailty”.

“With right policy settings, the labour market consequences of population ageing may take longer to crest than would initially be expected”.

Indeed, much of the worry about ageing centres on the ratio of persons over 65 to those of “working age”. This “dependency ratio” assumes that those over 65 do not work and rely economically on those aged 15 to 64, and that there will not be enough people of “working age” to complete all of the required jobs.

Both of these assumptions are incorrect and misleading.

Improved pay and working conditions will encourage more people to enter the workforce, even those over the age of 65. This is what economic theory predicts the labour market to do.

Increasing immigration to ‘solve’ population ageing is also bad economics.

The argument for increased immigration usually goes something like this: migrants are younger than the current population. As a result, importing people through immigration reduces the average age of the population, addressing the ‘issue’ of population ageing.

However, this reasoning is absurd, as migrants also age. As a result, immigration can only delay population ageing while also adding a slew of other economic and environmental costs associated with a significantly larger population, such as lower worker wages, overburdened infrastructure, increased traffic congestion, forcing people to live in apartments rather than houses, and environmental degradation.

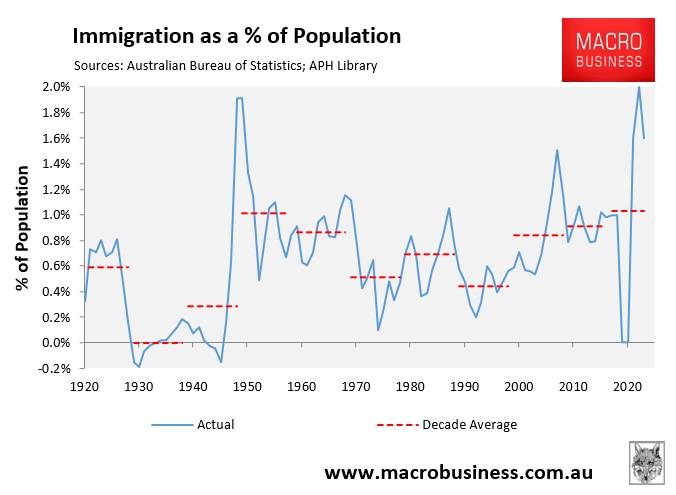

Indeed, a fundamental driver of Australia’s current ‘baby boomer bulge’ and our ageing population is the postwar mass immigration program (i.e., 1950s and 1960s):

These migrants are now elderly and contribute to Australia’s current ageing ‘crisis’.

Therefore, importing additional migrants to remedy the ageing issue is classic ‘can-kick economics’, because today’s migrants will grow old, causing ageing concerns in 40 years.

Some of these migrants will also bring their older family members into Australia on family reunion visas, aggravating the current population ageing trend.

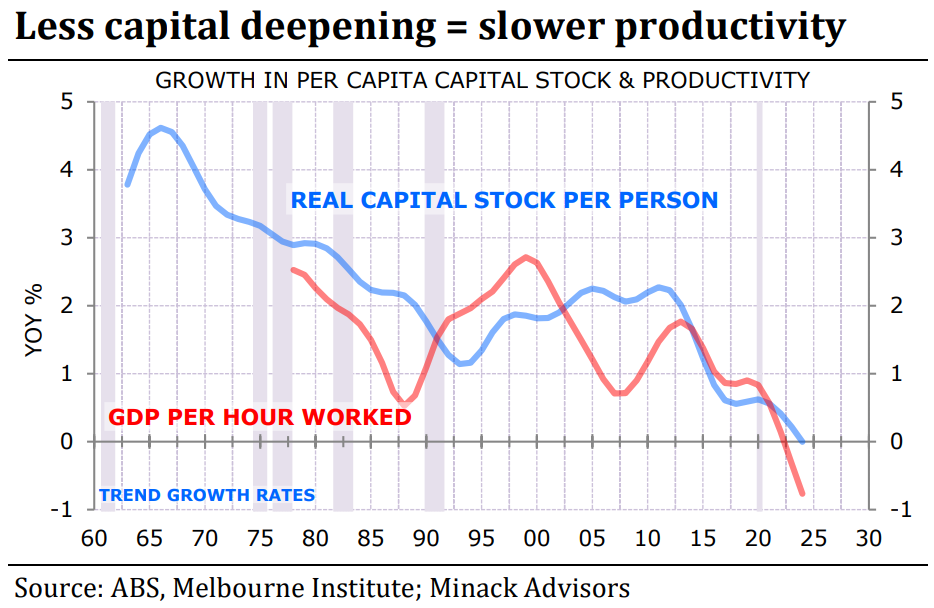

Finally, running a high immigration program helps to lower wage growth, disincentivising businesses from undertaking labour saving investments in automotation.

As a result, capital deepening is reduced, harming productivity.

The only realistic way of reducing the economic impacts of population ageing is to increase productivity, supplemented by increasing labour force participation.

Mass immigration weakens productivity and is also detrimental to the environment and living standards.