Why Australia sucks at building homes

Australian Industry Group’s analysis of data from the Productivity Commission underlines the downturn in the nation’s housing sector.

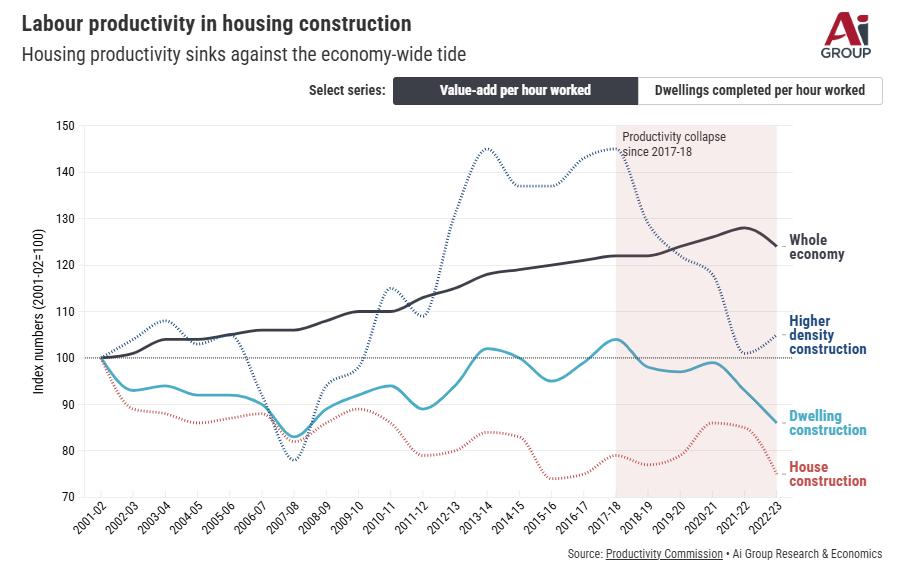

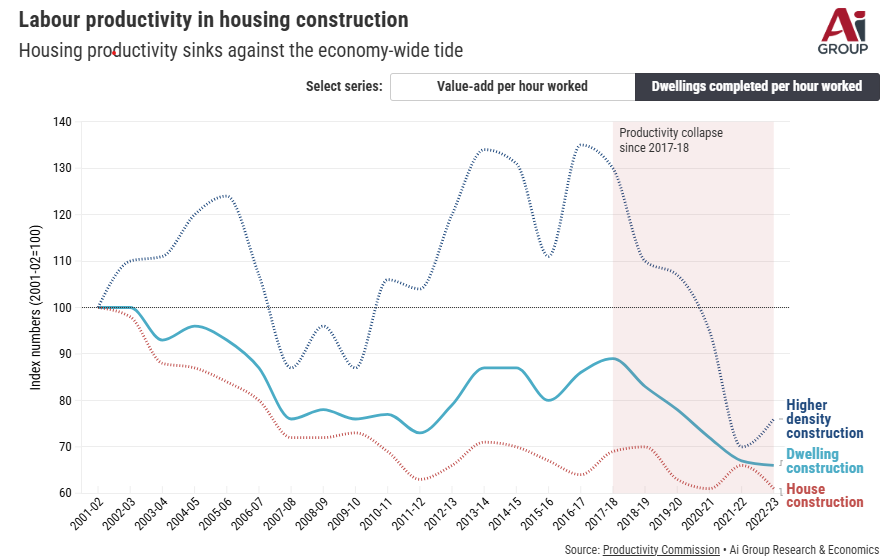

The Ai Group’s report shows that while labour productivity across the economy has increased by 24% over the last decade, this metric has fallen by 14% in relation to overall housing construction over the same period, and by 25% for detached homes.

There has been a corresponding decline in the number of homes built per hour worked.

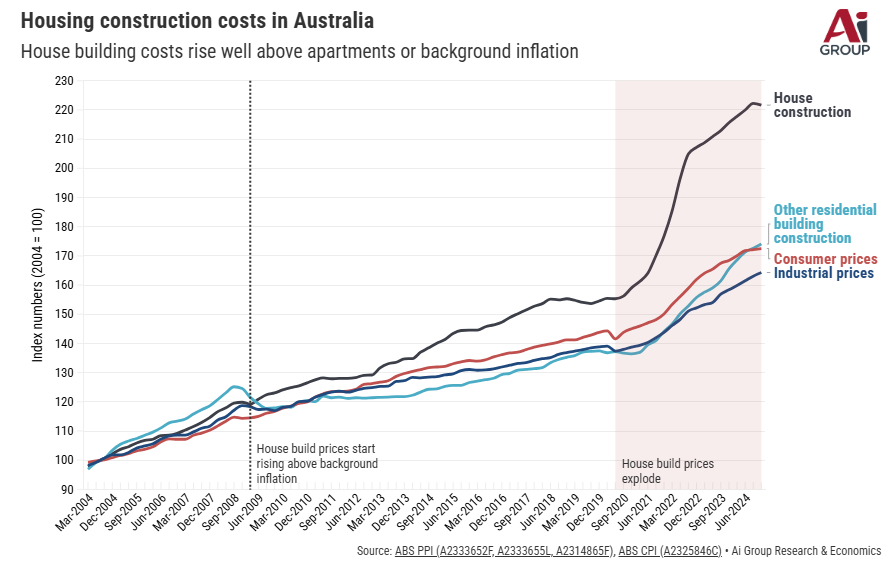

Ai Group warns that the productivity decline “results in higher costs for construction—as more labour is required to produce the same amount of housing—eating into business margins and profitability. It drives prices higher as builders have to recover these labour costs. It also exacerbates skills shortages, as the constrained construction workforce is being used less efficiently”.

Ai Group also warns that “chronic workforce shortages plaguing the industry”, with “64% of construction business identifying barriers to innovation, cited a ‘lack of skilled workers’ as their primary barrier”.

“In addition to cost and margin pressures, the construction industry is also struggling to secure enough labour, which is putting even more strain on builders. The sector relies heavily on skilled trades, and these trades are currently in severe shortage. According to Jobs and Skills Australia, every occupation within the construction trades field was identified as facing a national shortage in 2023, making construction the most labour-shortage-affected industry in Australia”.

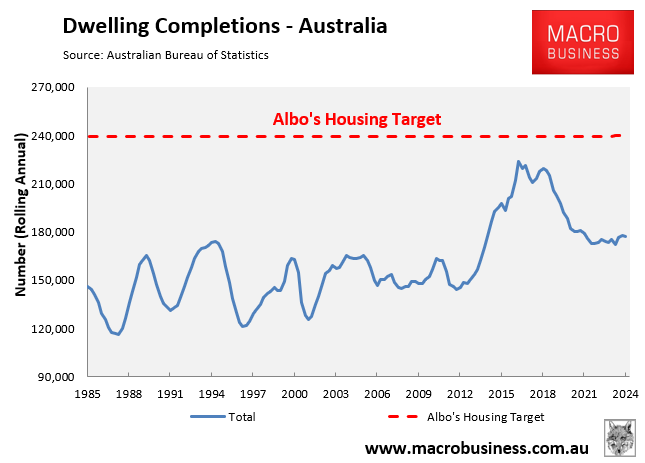

Ai Group CEO Innes Willox told The Australian that the productivity decline in the construction sector means there is “little chance” that the federal government’s target of building 1.2 million new dwellings over five years will be achieved.

“Trying to extract more houses from an industry with declining productivity is like filling a bucket with a widening hole”, he said. “Without action to turn around this decade-long decline, Australia has little chance of meeting its targets, or ensuring affordable and secure housing for our changing population.”

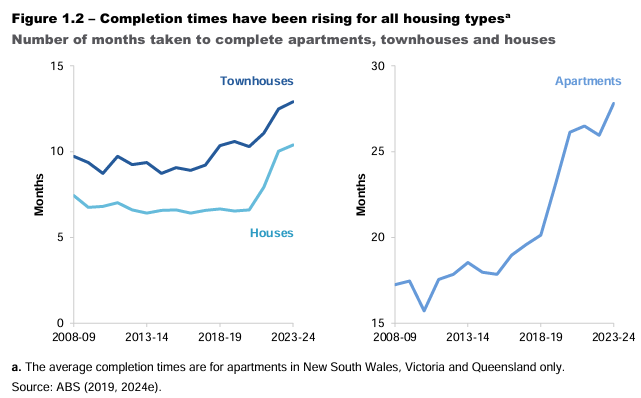

The Productivity Commission’s recent research paper entitled Housing Construction Productivity: Can we Fix it? also showed that the average time to complete new housing has increased significantly.

In 2023-24, the average time to complete a single detached house was around 10.4 months, up from 6.4 months a decade earlier. The average time to complete new townhouses rose from about 9.4 months to 12.9 months. For new apartments, it rose from about 18.5 months to 27.8 months.

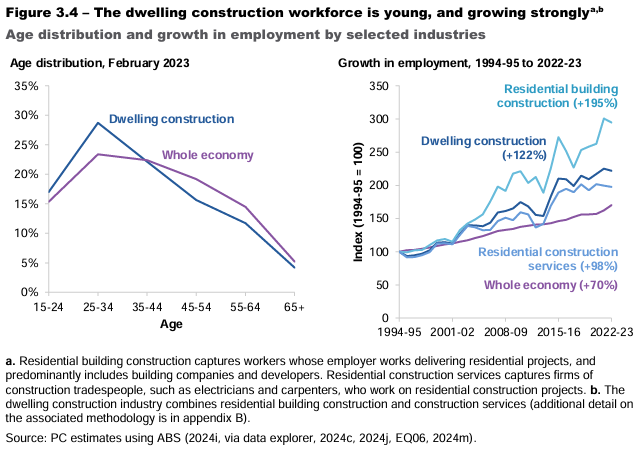

The PC report also noted that the construction workforce has grown strongly over recent decades compared to the broader economy. Moreover, despite frequent claims of ageing, the construction workforce is also younger than the wider economy.

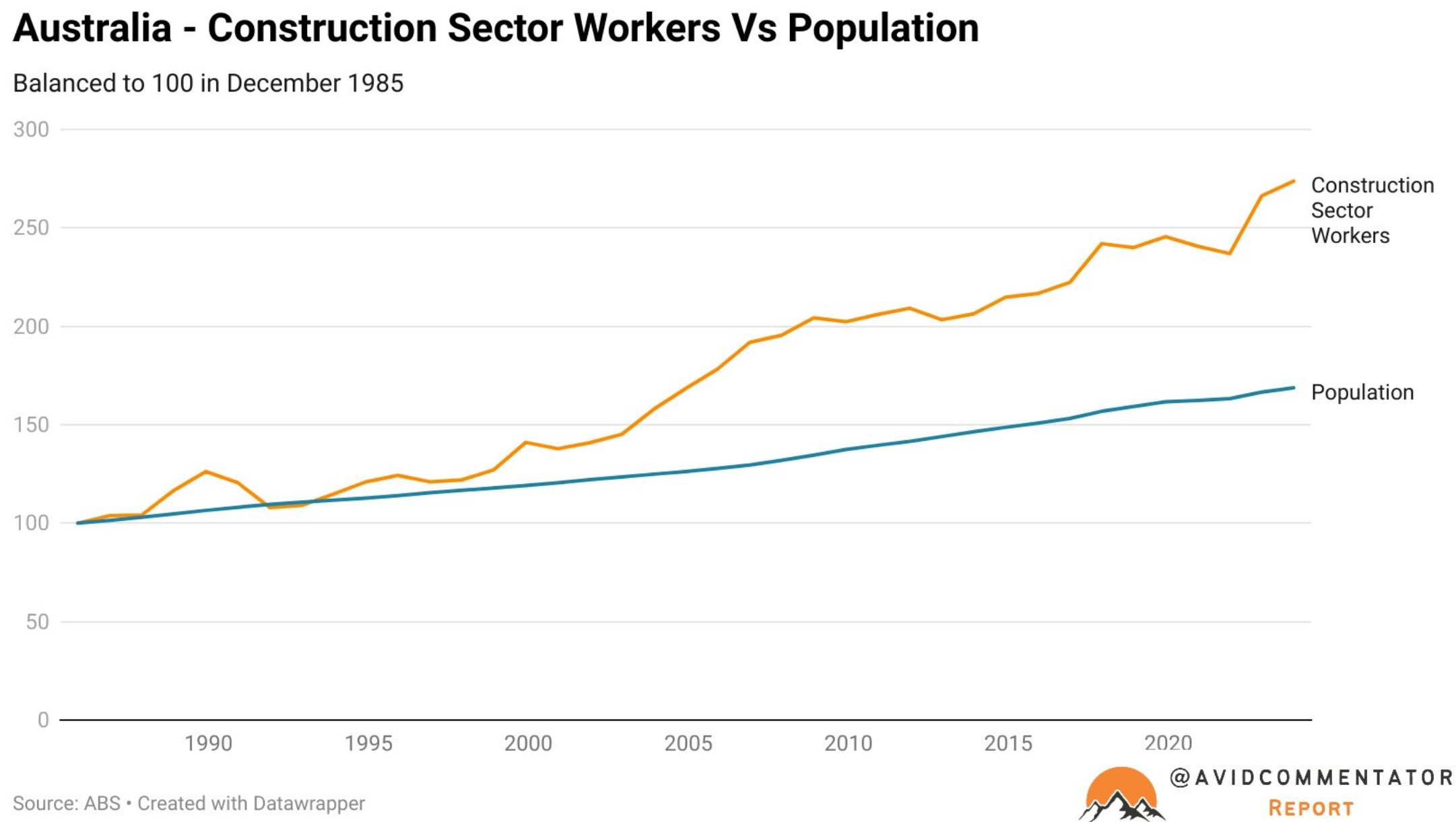

The chart directly above challenges the claim that a lack of construction workers is driving Australia’s housing shortage.

Independent economist Tarric Brooker similarly showed that “since 1994, the construction sector has expanded at a much faster rate than the population, with the sector growing by 126.3% compared with 49.6% for the broader population”.

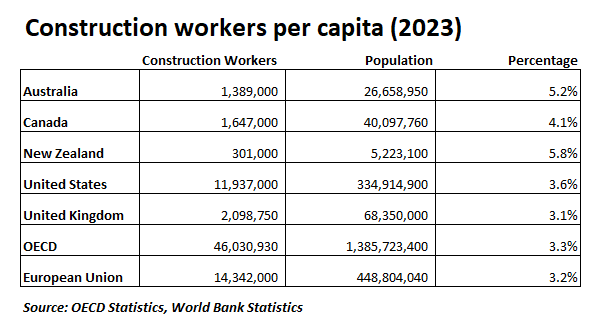

Australia had one of the highest numbers of construction workers per capita in the OECD in 2023, as illustrated below.

Why has Australia’s construction workforce expanded so rapidly without a corresponding increase in residential construction?

According to recent analysis by RLB Oceania, Australia’s construction sector has been overrun by back-office suits rather than tradies, resulting in a larger workforce but reduced productivity.

“The rapid rise in the number of professional workers that are now required to deliver projects across the country is at odds with the number of workers ‘on the tools’”, RLB’s Oceania director of research, Domenic Schiafone, noted in August 2024.

“In 2003, professional workers accounted for 28% of the construction workforce. By 2023, this had risen to 38%.”

The AFR’s Michael Bleby observed that “the industry as a whole is suffering from an imbalance of too few workers on the ground and too many in the office”.

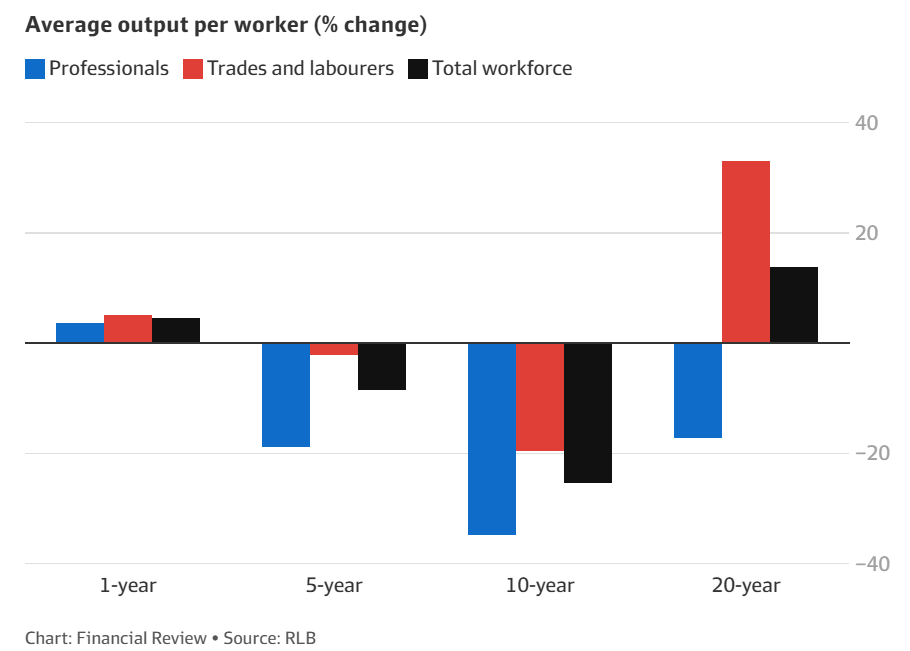

This growth of suits accounts for most of the decline in productivity across the construction industry:

“The growth in professional employees – professionals with tertiary degrees and building technicians with advanced diplomas – surged, rising 125% over the two decades from 242,900 to 547,300”, Bleby wrote.

“But the annual output per professional worker fell 17.2% to $470,900 from $568,900”.

Australia’s construction sector has been left with a large workforce in aggregate but insufficient front-line workers on the tools.