Commerzebank with the note.

Manufacturing PMIs showed initial damage

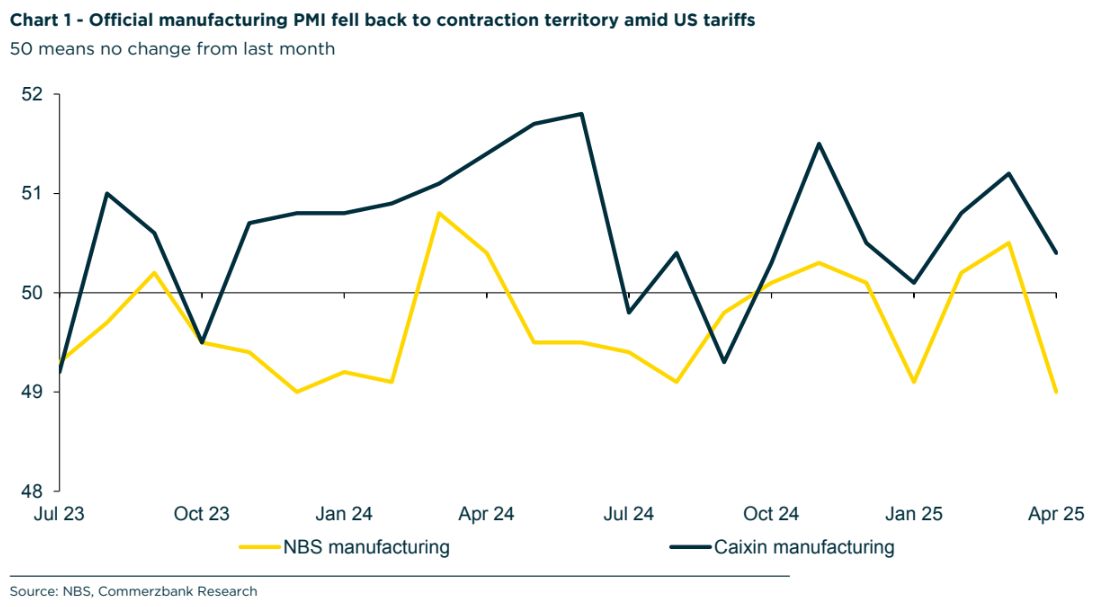

The official manufacturing PMI fell to contraction territory at 49.0 in April from 50.5 in March, the lowest since December 2023 (Chart 1). The decline was due to a drop in production and new orders which both fell into contraction territory. In particular, new export orders fell sharply to 44.7 from 49.0 previously. This is the lowest since December 2022, indicating that Chinese exporters have started suffering from the US tariffs.

The outprice price subindex also dipped further in contraction territory to 44.8 from 47.9 in March, suggesting that manufacturers lowered their prices as demand faltered.

News reported that Chinese exports to the US fell sharply in the final 10 days of April, after an improvement seen in the first half of the month likely due to the frontloading of shipments.

Ports on the US West Coast and bookings for shipping containers also expect sharp double-digit fall in early May.

The Caixin manufacturing PMI (a private survey that covers more smaller and export-oriented companies) also fell to 50.4 in April, albeit remaining in expansion territory, from 51.2 in March. The decline was due to a fall in new export orders. However, while firms are concerned about the tariffs’ impact, they maintained an optimistic outlook for output amid hopes that new product development and supportive government policies could spur sales in the year ahead.

Meanwhile, the official non-manufacturing PMI slipped to 50.4 in April from 50.8 in March. The construction subindex eased but remained solid as the frontloading of fiscal spending is taking place.

The services subindex stood at 50.1 in March.

The reading has continued to be disappointing.

High-level trade talks will unlikely start any time soon

US President Donald Trump and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent have struck a more conciliatory tone recently.

There have been reports that the White House may lower tariffs on China from 145% to 50-65%, and that Beijing may also lower tariffs for selected US goods that China remains reliant on.

In our opinion, Beijing appears not to be in a hurry to negotiate with the US and is determined to counter the negative impact from US tariffs by strengthening domestic consumption.

Beijing has said that the US should thoroughly remove all unilateral tariffs imposed on China first, while US Treasury Secretary Bessent said that it is up to China to take the first step in de-escalating the tariff war.

Even if the US and China could start any trade negotiations, the talks will unlikely result in any material outcomes quickly.

145% or 50-65% don’t matter

Our estimate suggests that the US-China tariffs would trim China’s GDP by 2% or more over the next two years.

The additional US tariffs could potentially reduce direct US imports from China by over 80%.

Whether the additional tariff is at 145% or 50-65%, the tariff level is prohibitive, effectively blocking imports unless no substitutes can be found elsewhere.

What’s more, China can only to a lesser extent rely on third countries to export products to the US.

In one scenario, Trump’s tariffs could push some of the Southeast Asian countries closer to China.

In this case, trade negotiations between the US and these countries may not result in positive outcomes, and the US will impose high reciprocal tariffs on these countries.

In another scenario, trade negotiations may actually result in some of these countries imposing tariffs or other trade barriers on China in return for lower US tariffs.

Either way, Chinese exporters would find it costlier to divert trade to the US via a third country.

As such, Chinese companies will try to export to other markets, notably the European market and also the Belt and Road countries.

While this may help China to mitigate the US tariff impact to a certain degree, it will possibly raise trade tensions with other countries.

Much more damage to come.