High house prices are strangling Australia

Cotality (formerly CoreLogic) reported that the total value of Australia’s housing stock was $11.3 trillion as of April 30, 2025, with the average home worth exactly $1 million.

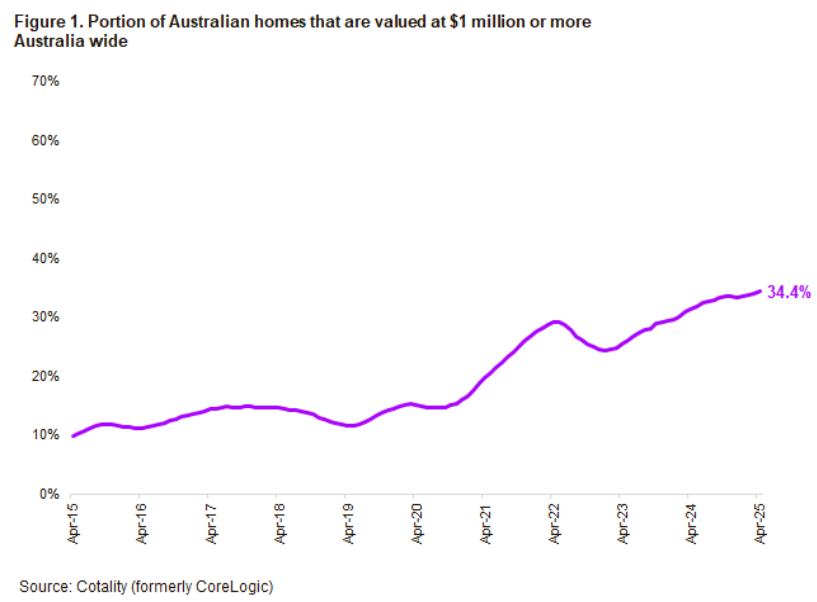

New research from Cotality shows that a record 34.4% of homes across the nation were valued above $1 million in April, with 41.6% of capital city homes priced above $1 million.

“The trend reflects strong price growth across Australia’s housing market, where values have increased 67.3% in the past ten years”, noted Eliza Owen, Head of Research at Cotality.

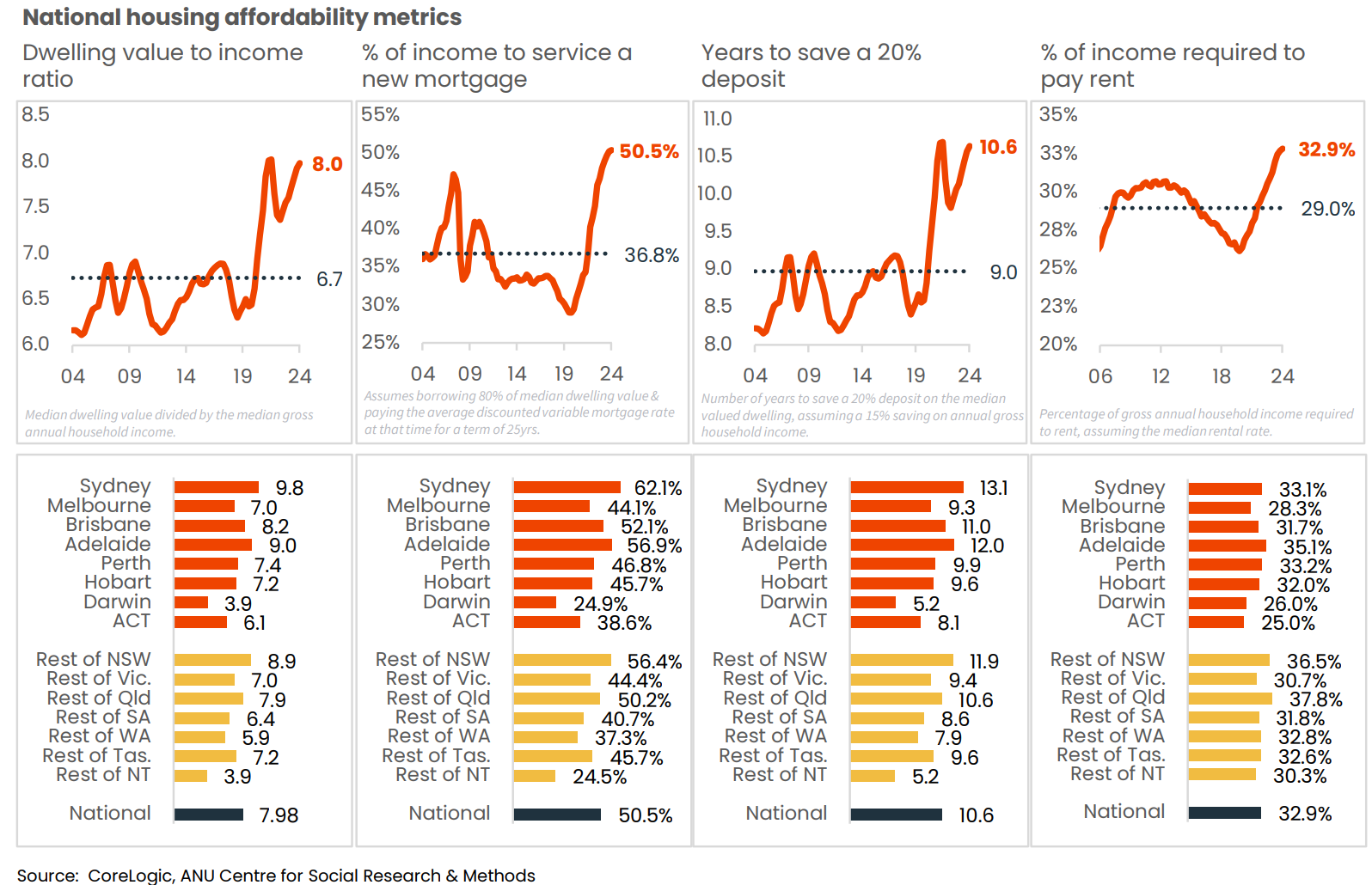

Sydney has the worst affordability, with 64.4% of homes valued above $1 million.

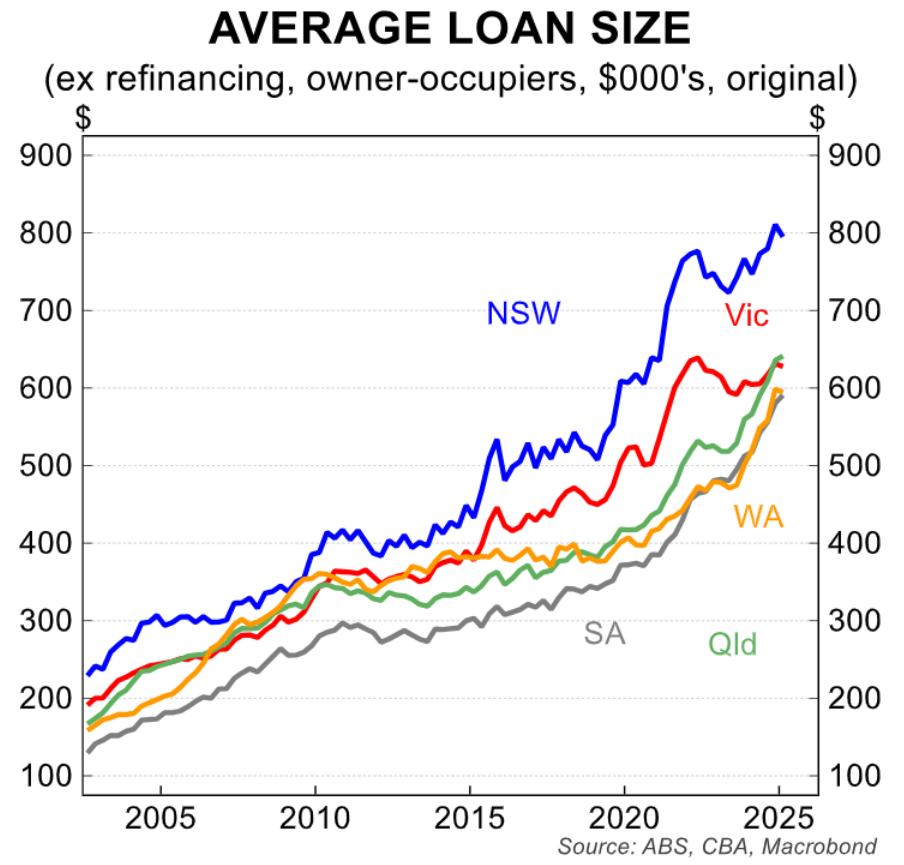

This result matches the latest analysis from CBA showing that the average loan size in NSW is around $800,000, well above the other markets.

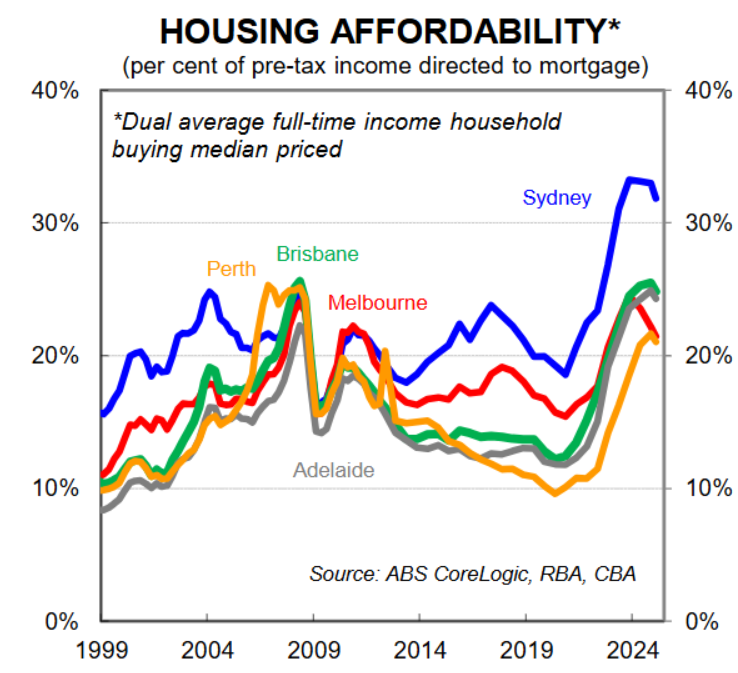

The percentage of income required to service a new mortgage on a median-priced Sydney home was also well above the other capitals and tracking close to a record high in April.

Eliza Owen argues that Australia’s expensive housing is a double-edged sword for the nation:

Australia’s million-dollar housing markets are in part a reflection of our wealth and prosperity as a nation. After all, housing markets wouldn’t have a million-dollar price tag if at least some Australians couldn’t come up with that level of finance. As values continue to rise, the chance that homeowners hit millionaire status increases, opening up new opportunities for further investment, or accessing that wealth through the sale of a property.

However, the downsides of such an extraordinary price point are also increasingly evident.

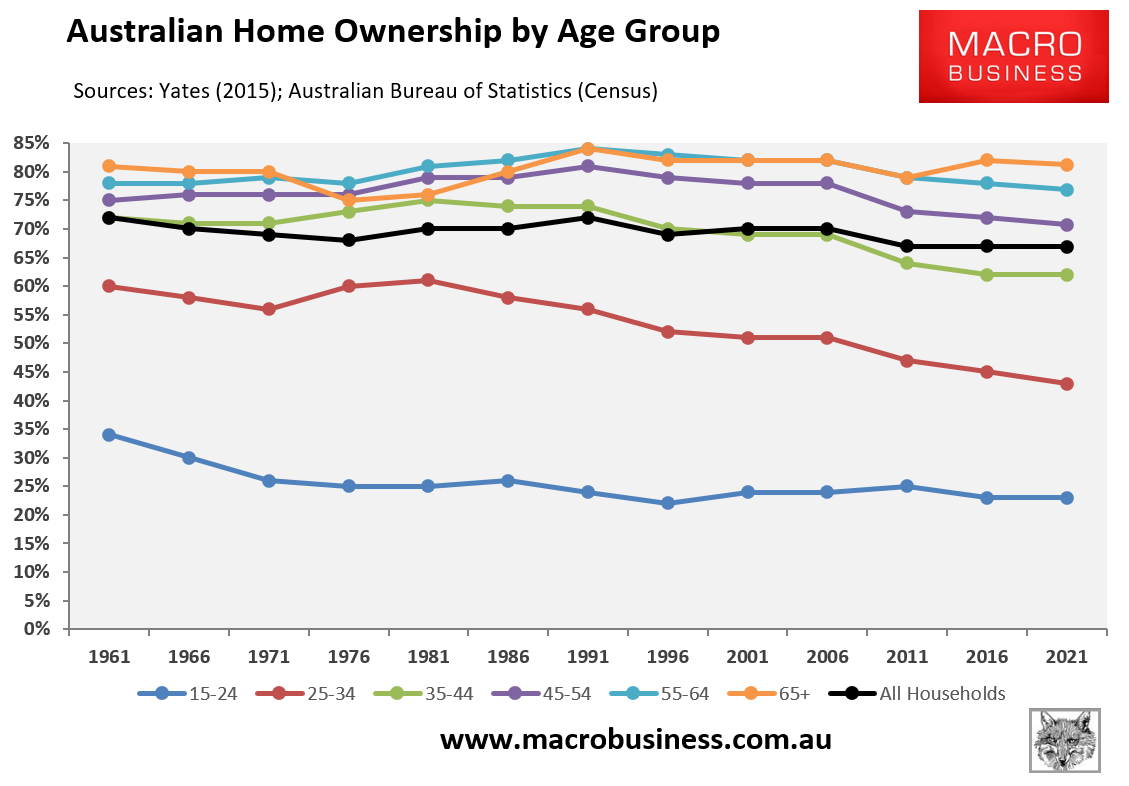

The rate of home ownership has gradually declined over time, particularly among younger, low-income households where income cannot keep pace with growth. The average age of first home buyers has increased, and increasingly wealthy households are stuck renting for longer, which increases competition for low income, renting households.

Housing debt has also blown out to keep pace with rising values relative to more subdued wages growth. Housing debt relative to income was recorded by the RBA at 135% at the end of last year (albeit down from a high of 139% before the bulk of cash rate rises in September 2022). This was up from 122% a decade prior.

I strongly believe that the negatives of expensive housing far outweigh any positives.

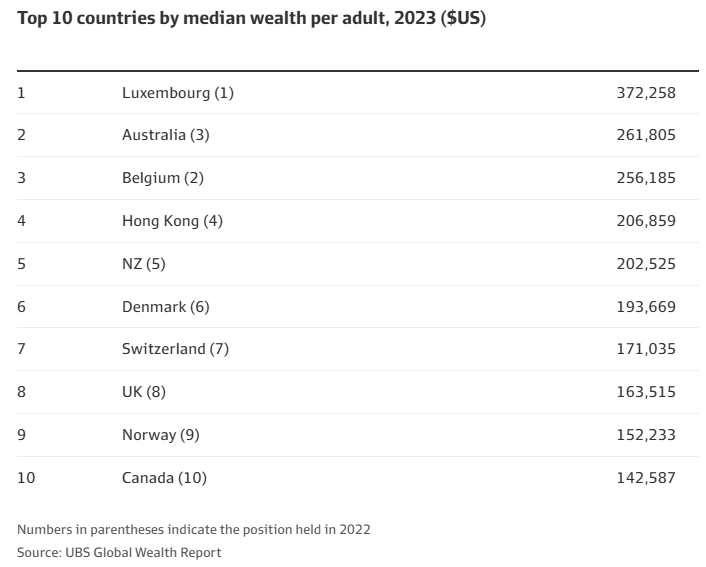

The increase in average property values to $1 million has theoretically made Australians some of the wealthiest people on the planet.

According to the UBS Global Wealth Report, Australian households have the world’s second highest net worth.

However, most of Australia’s wealth is illusory, and expensive property is gradually strangling the economy.

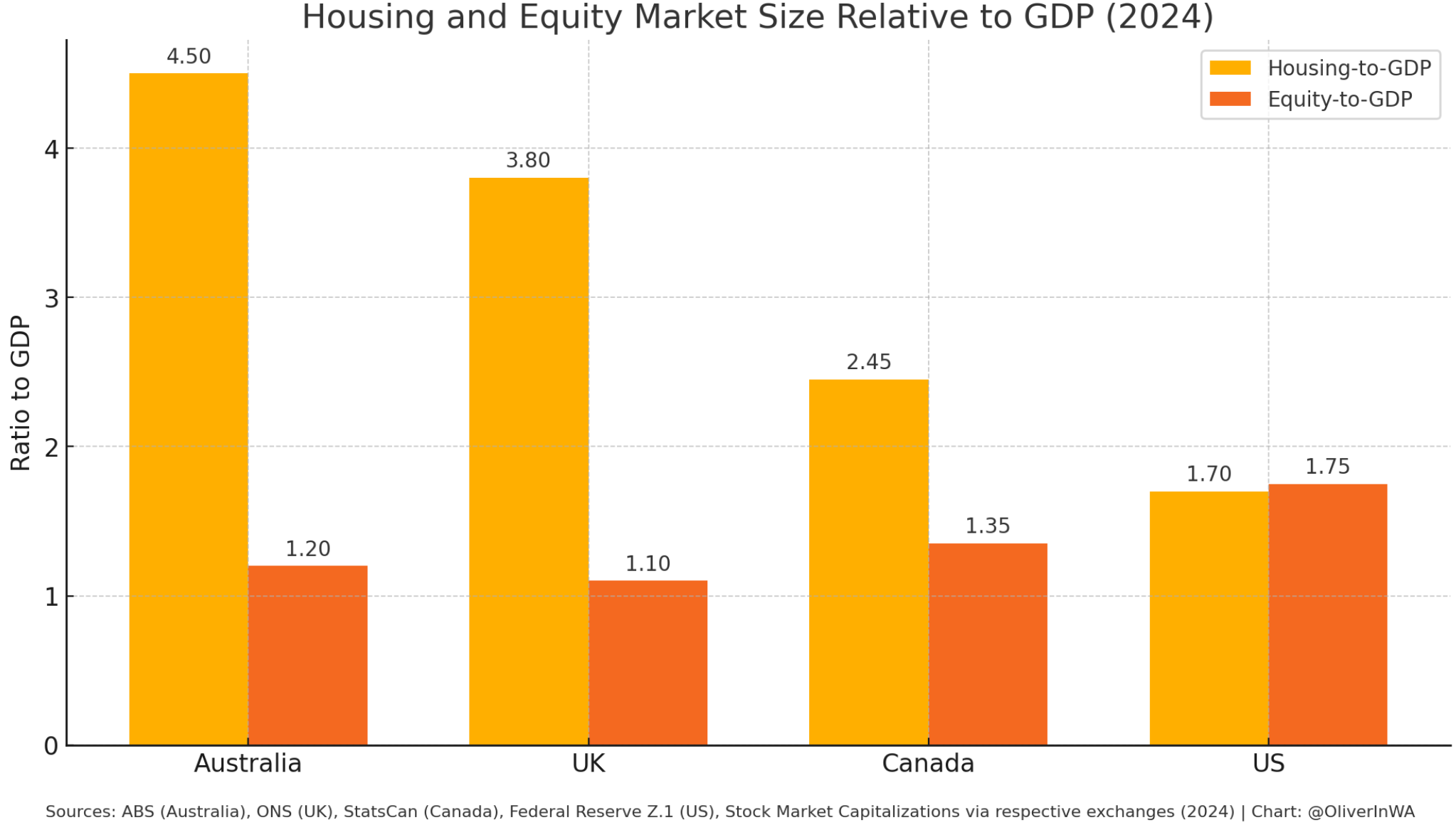

Australia is significantly overweight in housing (4.5 times GDP) and slightly underweight in shares (1.2 times GDP). Australians invest more of their wealth in housing and less in shares than other English-speaking countries.

The comparison with the United States is particularly stark, with US housing valued at barely 1.7 times GDP and shares valued at 1.75 times GDP.

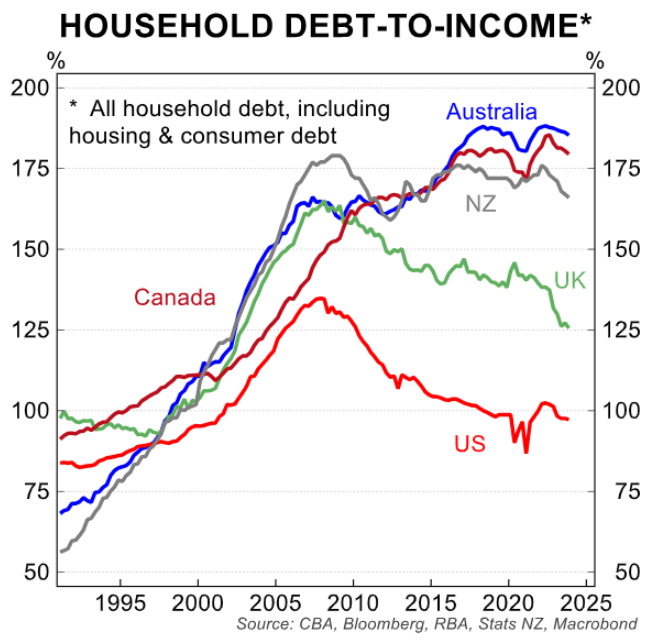

Australian households also have some of the world’s highest debt levels.

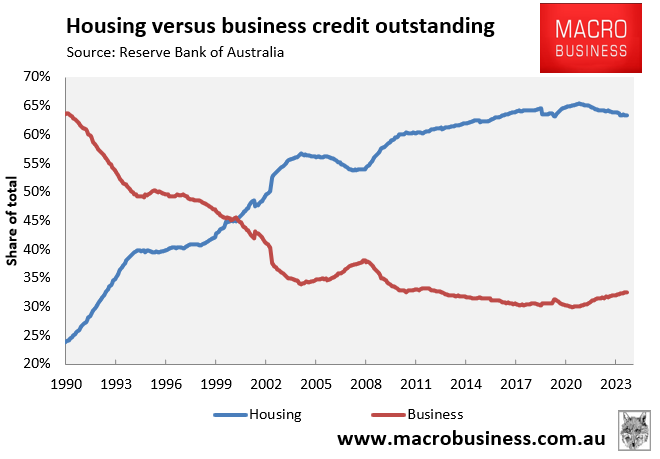

The flood of capital into property has arguably deprived firms of investment and reduced Australia’s productivity.

Australia’s banks have grown into giant building societies that prioritise lending for housing over productive businesses.

In 1990, businesses received around two-thirds of all bank loans, with mortgages accounting for only about a quarter. Thirty-five years later, the ratio has flipped, with nearly two-thirds of bank loans for housing and only one-third for businesses.

Australians would benefit from lower property prices:

Australians are struggling financially, despite having some of the world’s wealthiest households.

Many Australians are buckling under the weight of mortgage and rent payments, which, according to Cotality, are consuming a record amount of income.

Given that housing affordability is tracking near an all-time low and our younger generations are unable to purchase a home without parental financial aid, how can Australian households be ranked the world’s second wealthiest?

Australians would be wealthier if the average property were worth $500,000 instead of $1 million and household debt was 90% of income rather than 180%.

Australia would be a far more egalitarian society, and we would be financially better off if our homes were half the price they are now, with half the debt.

According to the 1991 Census, Australia’s homeownership rate was roughly 5% higher than it is today, homes cost around three times income (compared to eight times today), and household debt was 70% of income, compared to 180% today. Banks also lent two-thirds to businesses and one-quarter to mortgages.

Despite having significantly less housing wealth, Australian households were far better off in 1991 than they are now. Australia’s economy was also far more balanced and diverse in 1991 than it is now.

Australia’s high housing prices have a negative impact on the younger and future generations, requiring them to pay substantially more for shelter than otherwise.

Whether a home is worth $500,000 or $2 million, it serves the same purpose: shelter. For most people who merely live in their homes, greater housing “wealth” holds little significance.

The economy would also be more balanced and productive if capital had been directed towards businesses rather than inflating housing values.

In this regard, Australia’s $11.3 trillion housing stock is a massive misallocation of capital that has ultimately harmed productivity, equity, and the broader economy.