Government forecasts permanent housing shortage

Nobody believed that the federal government’s target to build 1.2 million homes over five years was realistic.

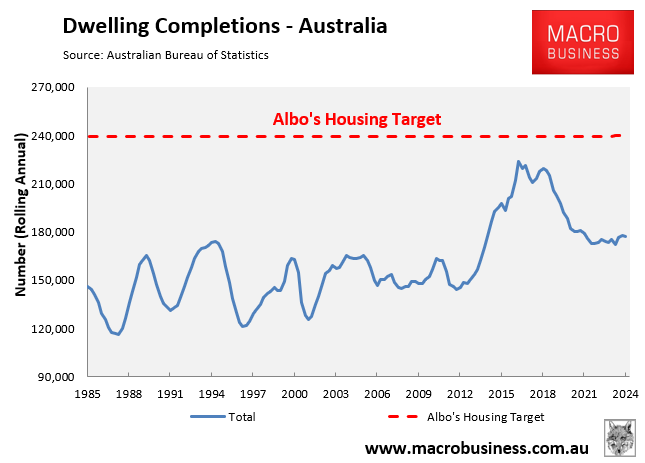

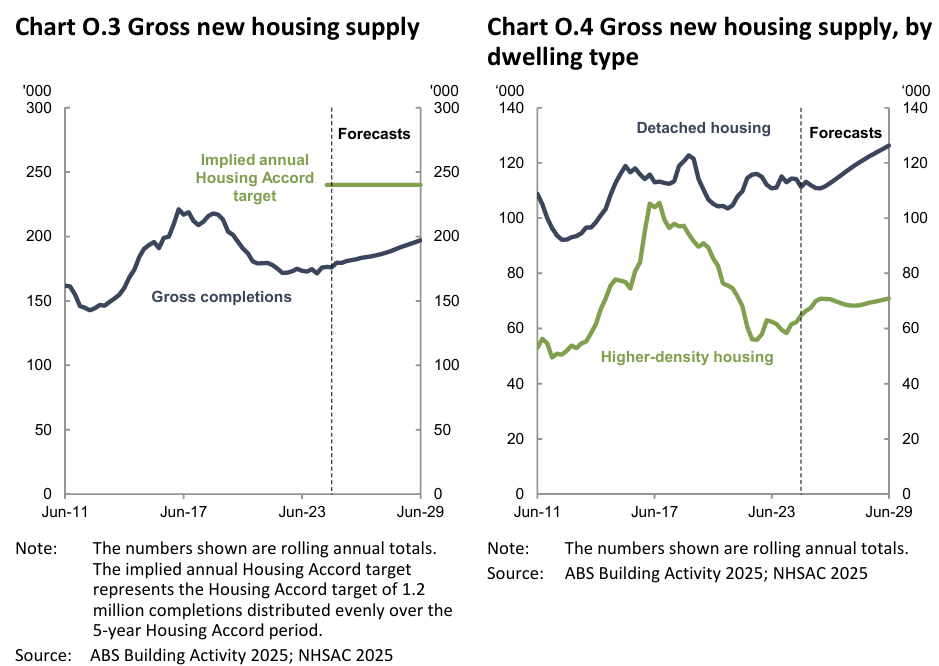

The highest single year of construction in Australia’s history was 225,500 in 2017, 6% below the annual target of 240,000 homes a year.

As shown above, new housing supply is tracking near decade lows, with only 177,000 new homes completed in 2024.

There are several reasons why housing construction is so poor.

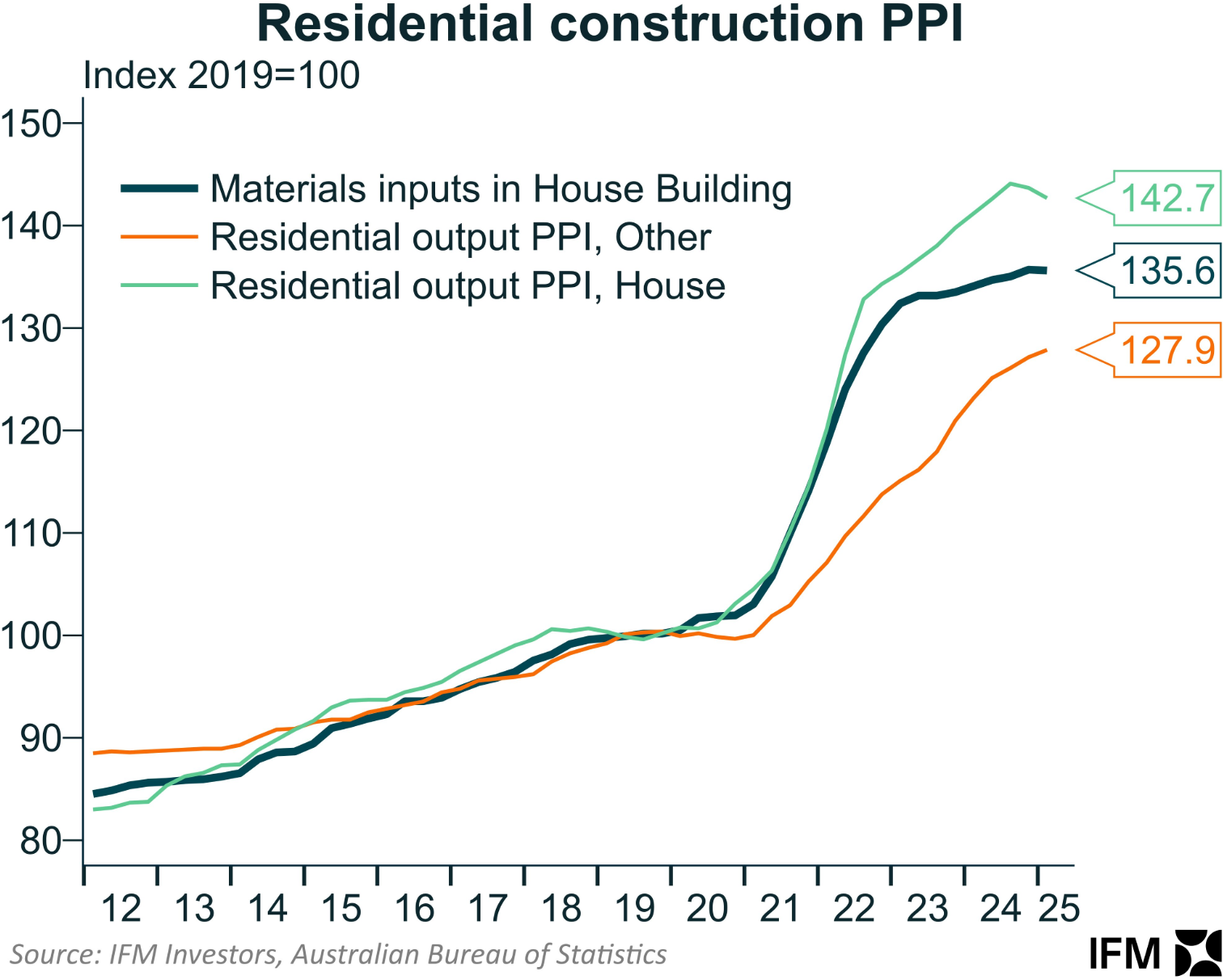

First, construction costs have increased by more than 40% since the start of the pandemic.

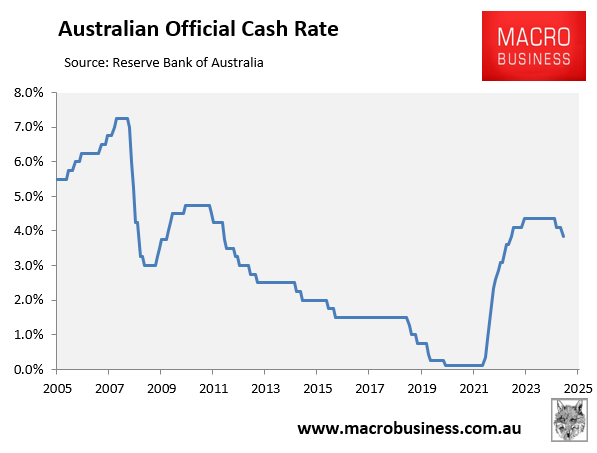

The official cash rate of 3.85% is significantly higher than the 1.5% official cash rate that was in effect in 2017, when construction peaked.

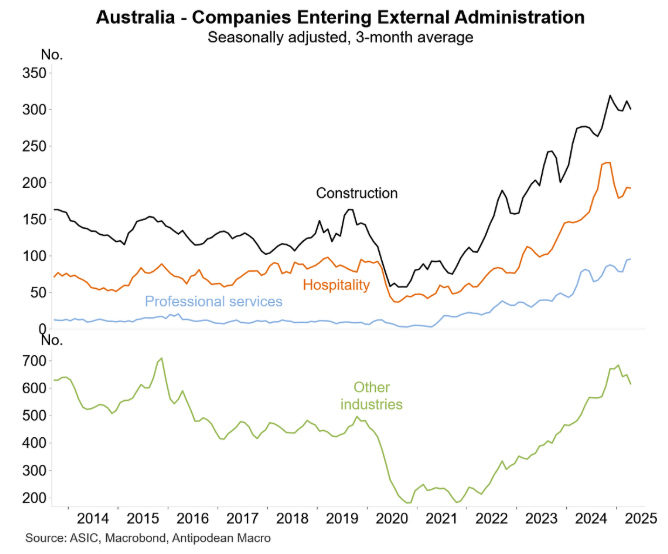

Record numbers of construction firms have collapsed, reducing capacity across the industry.

Finally, builders are competing with government infrastructure projects for scarce labor.

The National Housing Supply & Affordability Council (NHSAC) has released its 2025 State of the Housing System report, which expects only 938,000 dwellings to be built nationwide by mid-2029.

The forecast from the federal government’s advisory council is 262,000 dwellings short of Labor’s target of 1.2 million new homes over five years.

“The downgrade in the supply forecast reflects a range of factors, including an upward revision to interest rate assumptions and weaker-than-expected dwelling approvals over the past 12 months”, the report notes.

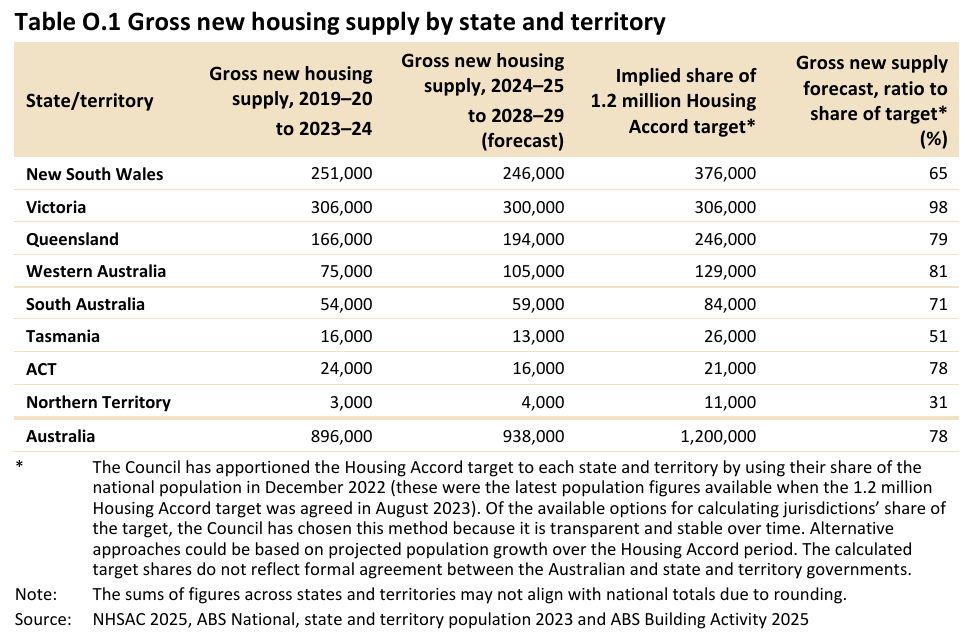

“All states and territories are projected to fall short of their implied share of the Housing Accord target”, as illustrated below.

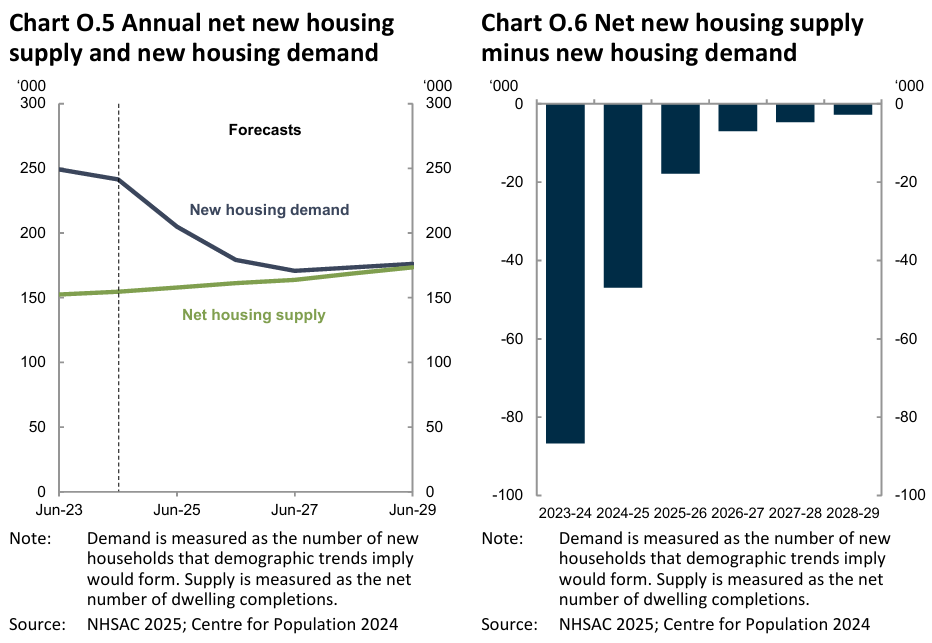

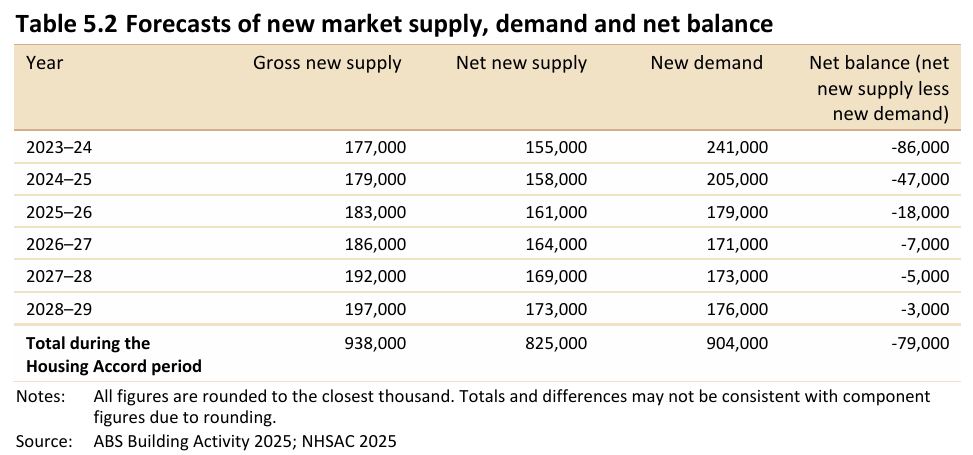

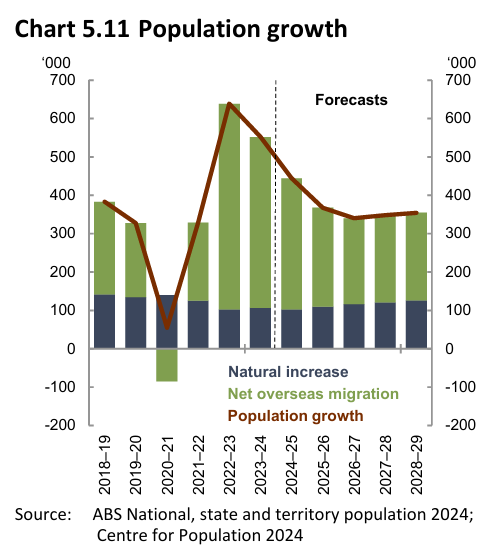

As a result, NHSAC forecasts that new housing supply will remain below population demand over the forecast period:

“After accounting for the expected demolition of around 113,000 dwellings, net new housing supply is projected to be 825,000 over the Housing Accord period, or just over 165,000 dwellings per year on average”, NHSAC says.

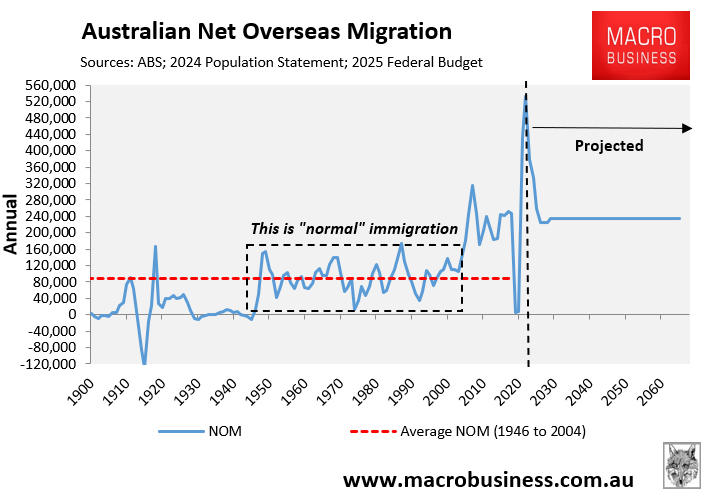

“In comparison, new underlying housing demand is forecast to be 904,000 households over the Housing Accord period. This reflects the still elevated demand of 205,000 in the 2024–25 financial year (with the surge in net overseas migration after the Pandemic still affecting the housing system), followed by a normalisation of demand to around 175,000 per year from 2025–26”.

“These projections of net supply and underlying demand imply a net shortfall of around 79,000 dwellings over the Housing Accord period”, NHSAC forecasts.

The NHSAC report argues that “the single biggest constraint on supply currently is that many housing projects are not commercially viable given current land, financing and development costs relative to expected sale prices”.

“These cyclical factors will remain a headwind to supply over the near term”, with NHSAC pointing to the following constraints:

- Labour shortages persist for some key trades, and labour availability forecasts indicate an overall deficit of labour supply relative to demand will persist.

- Material costs are expected to remain high relative to pre-Pandemic levels.

- Interest rates, despite falling, are expected to remain above the levels of the past 10 years, meaning financing costs for builders, developers, households and investors will remain elevated.

The NHSAC report warns that ongoing strong immigration, combined with poor supply, will continue to pressure renters and result in more homelessness and overcrowding.

“The excess of new demand relative to new supply over the Housing Accord period will worsen the existing undersupply of housing in the system and add to affordability pressures”, NHSAC says.

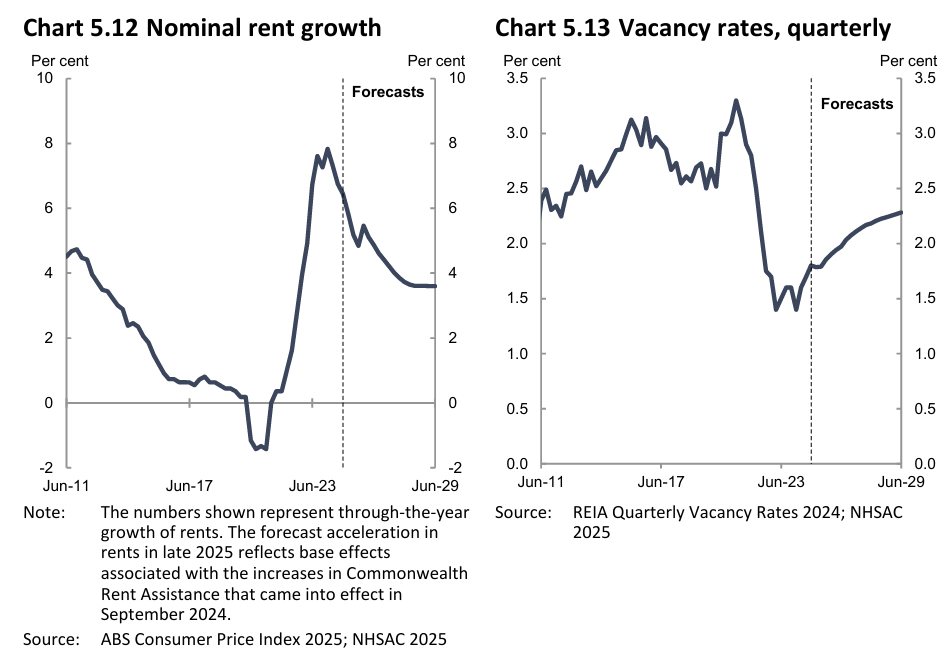

“Rent growth has started to ease and throughout the Housing Accord period is expected to continue slowing but remain above the RBA’s inflation target band of 2–3% (see Chart 5.12), adding to the already significant degree of rental stress in the system. Rental housing will remain scarce for households across the income spectrum as the vacancy rate remains below its historic average (see Chart 5.13)”.

“A lowered vacancy rate will absorb some of the unmet demand, and some will add to the homeless population. Some may be absorbed by suboptimal types of shelter not captured by traditional measures of the housing stock, such as caravan parks, hotels and emergency shelters. Most will be absorbed by households not forming that otherwise would have, resulting in larger households and more instances of overcrowding”, NHSAC warns.

Clearly, the only way to solve Australia’s housing shortage is for the federal government to slash net overseas migration.

Otherwise, Australia’s rental crisis will continue.

This week’s Treasury of Common Sense on Radio 2GB/4BC discusses NHSAC’s report.