Australia’s lost economic decade

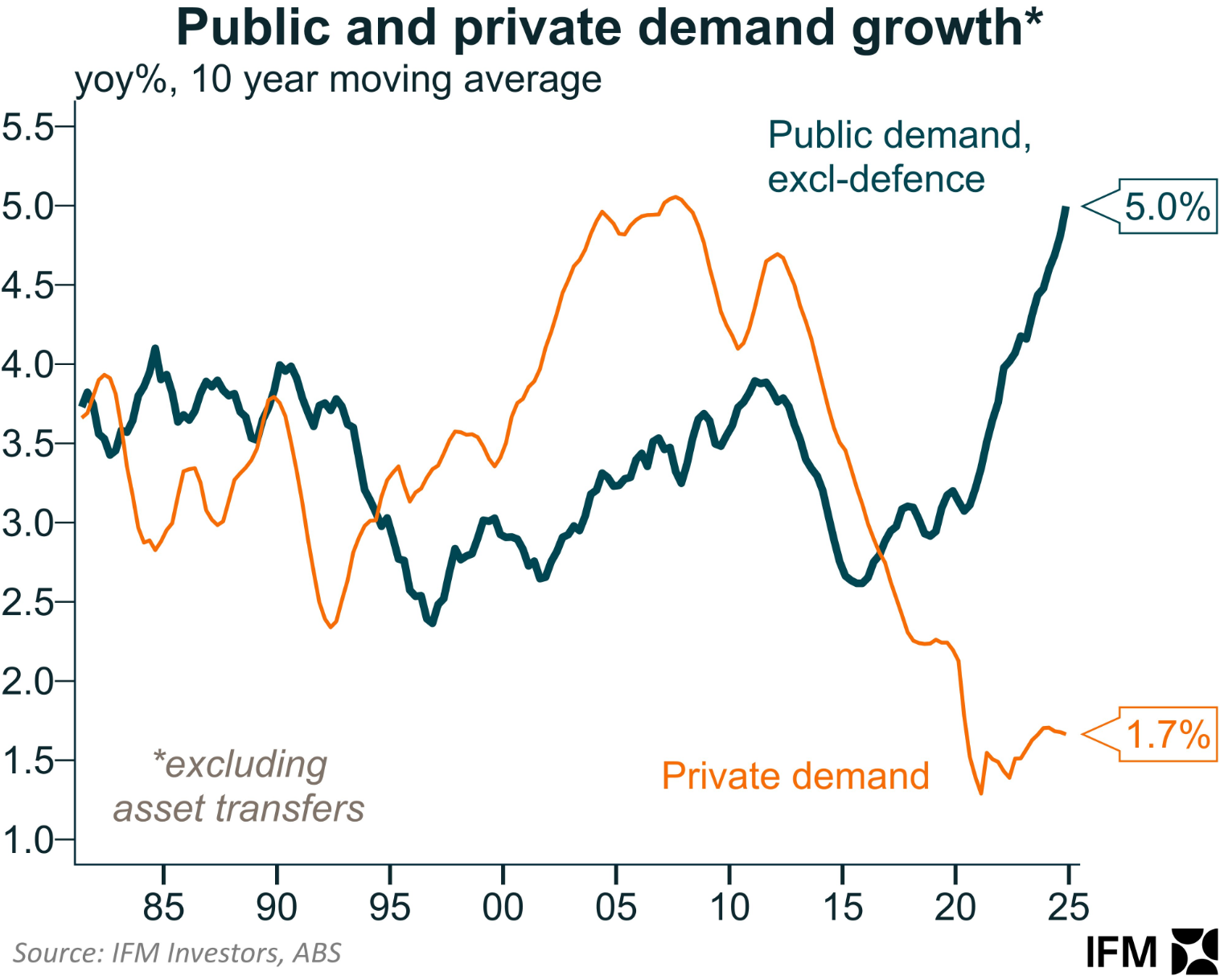

Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors, published the following chart showing the structural decline in private demand over the past decade, offset by the surge in public demand.

Joiner’s chart paints a picture of a ‘lost decade’ for the private sector economy.

Indeed, population growth averaged 1.5% over the past decade, implying per capita private demand growth of only around 0.2%.

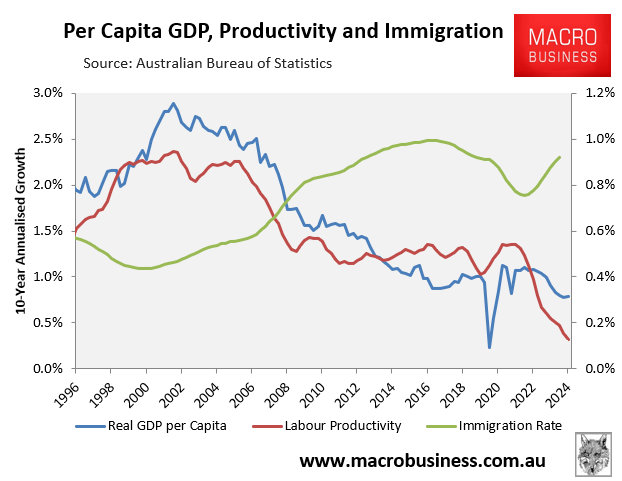

Other macroeconomic data supports this view.

The next chart shows that Australian labour productivity and per capita GDP growth also collapsed over the past decade:

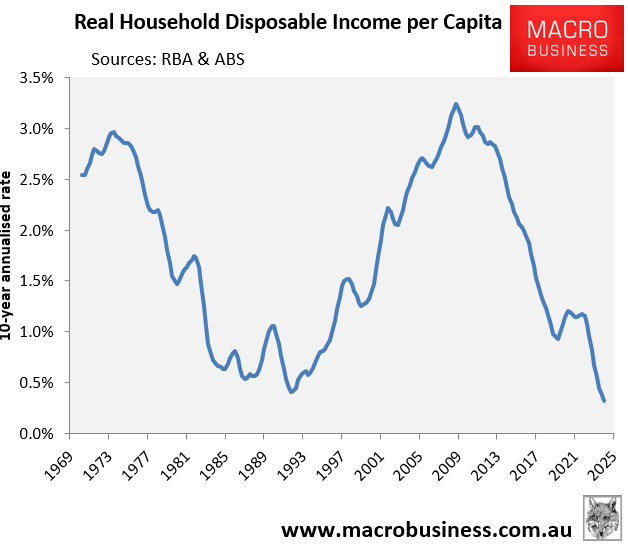

Real per capita household disposable incomes also collapsed to a record low of just 0.3% per annum over the past decade:

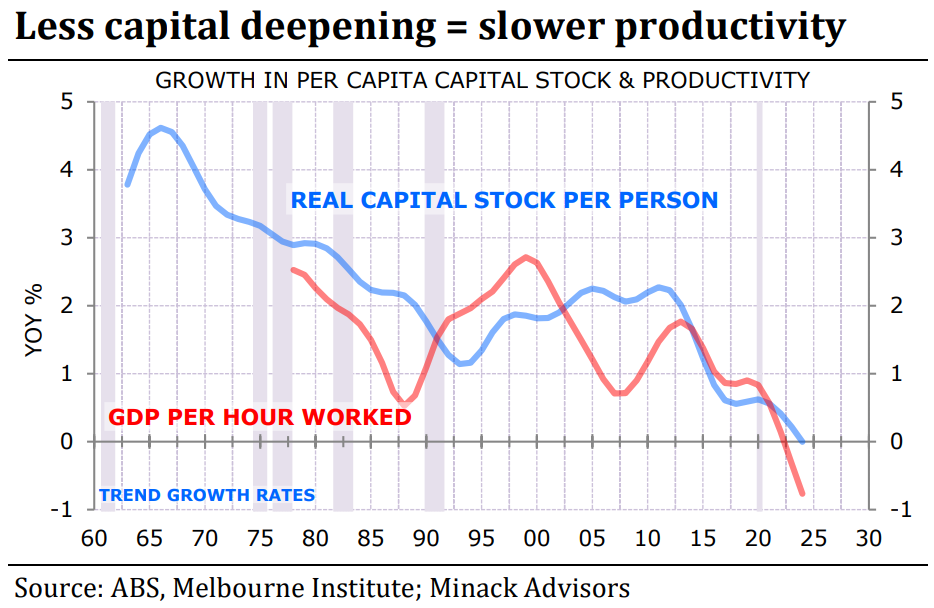

The primary issue is the sharp decline in Australia’s productivity, which I attribute to five key factors:

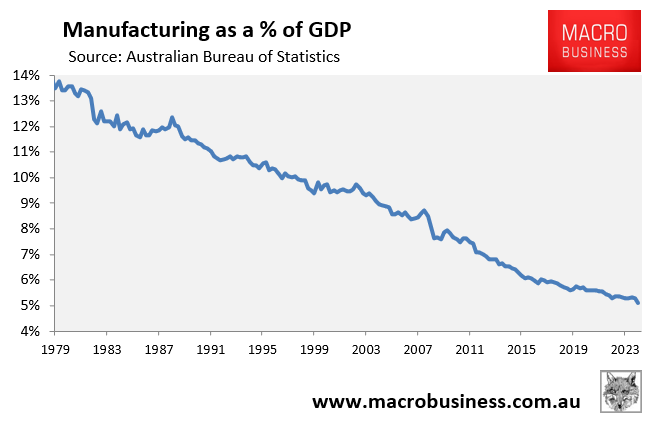

- The mining boom of the 2000s and the associated surge in the Australian dollar contributed to the contraction of Australia’s manufacturing sector.

- Capital shallowing, driven by record immigration without a corresponding acceleration in infrastructure and business investment.

- Explosive growth in the non-market economy, facilitated by the expansion of the NDIS.

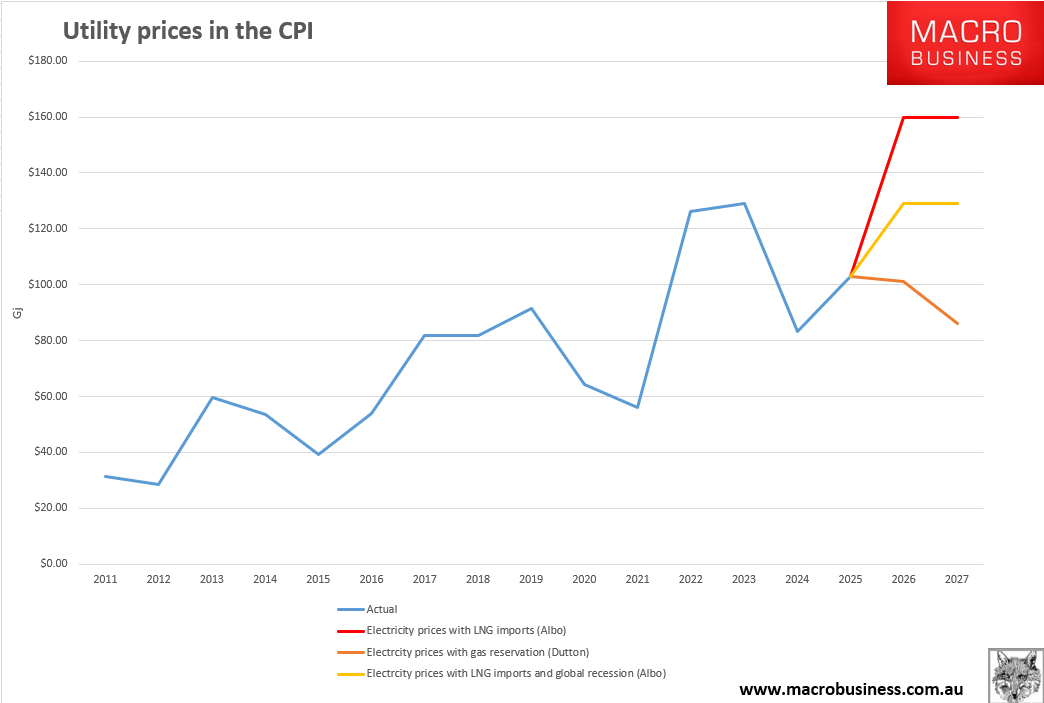

- Soaring energy costs, driven by gas policy failures and net-zero policies.

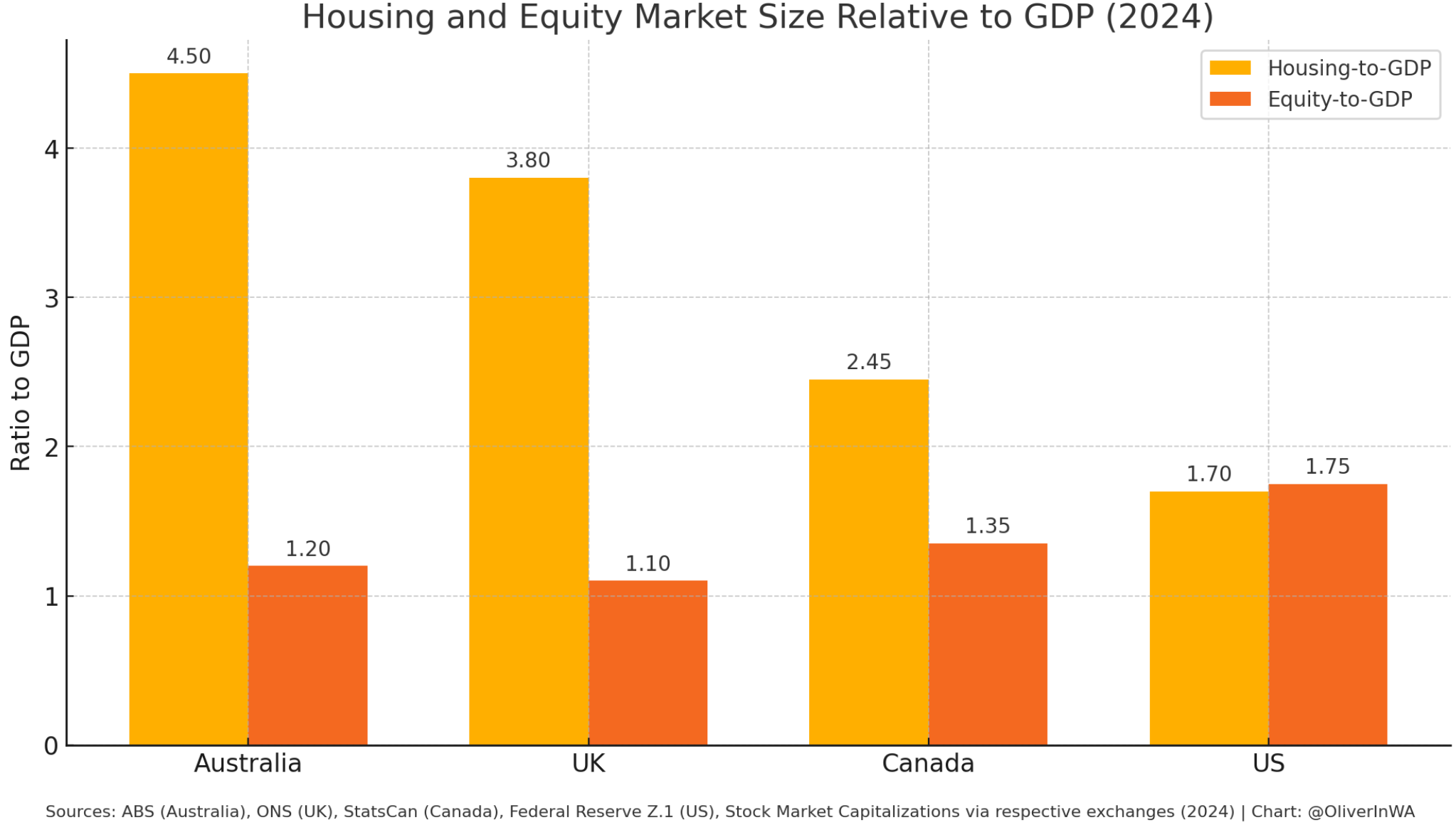

- Poor tax policies encouraging housing speculation over productive investment.

Australia’s prognosis is poor:

The long-term prospects for Australian productivity growth remain bleak, which augurs poorly for living standards.

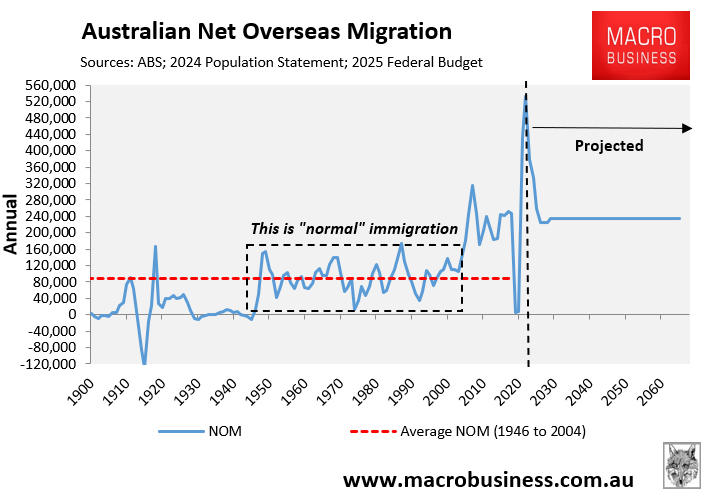

First, capital shallowing will continue as Australia’s population growth outpaces business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

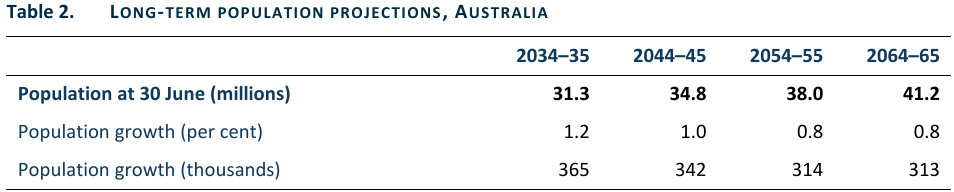

According to the 2024 Population Statement from Treasury’s Centre for Population, Australia’s population will increase by 13.5 million people in just 40 years.

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

This 13.5 million projected population gain will be driven by high net overseas migration of 235,000 per year, which is more than double the average net migration of 90,000 recorded in the 60 years following World War II.

This 13.5 million population rise is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the country’s current population in just 40 years.

To sustain, let alone boost, current productivity growth, the housing, infrastructure, and business investment in these three large cities would have to be replicated in just 40 years. That’s an impossible task.

Second, the Albanese government refused to follow the Coalition’s policy of reserving gas on the East Coast and has pledged to replace traditional baseload energy generation with costly and intermittent renewables.

As a result, LNG imports are scheduled to begin at the end of this year or early next year, potentially raising the East Coast gas price to $20 per gigajoule or more from around $12 currently.

LNG imports will become the marginal price setter for East Coast electricity once energy rebates expire.

Inflation will rise (other things equal), cost-of-living pressures will persist, and Australia will continue to deindustrialise as it becomes prohibitively expensive to manufacture anything here, resulting in a less diverse and productive economy.

Finally, the Albanese government has pledged to use the federal budget to inject more capital into housing.

Labor has committed to creating a state-sponsored subprime mortgage scheme by allowing all first-time home buyers to purchase a home with only a 5% deposit, with the government (taxpayers) guaranteeing 15% of the loan.

Labor has also instructed mortgage lenders to ignore student debts in their loan serviceability evaluations.

As a result of the above, Australia’s economy will remain trapped in a productivity death spiral and living standards will continue to suffer.