Australia’s economy shallows out

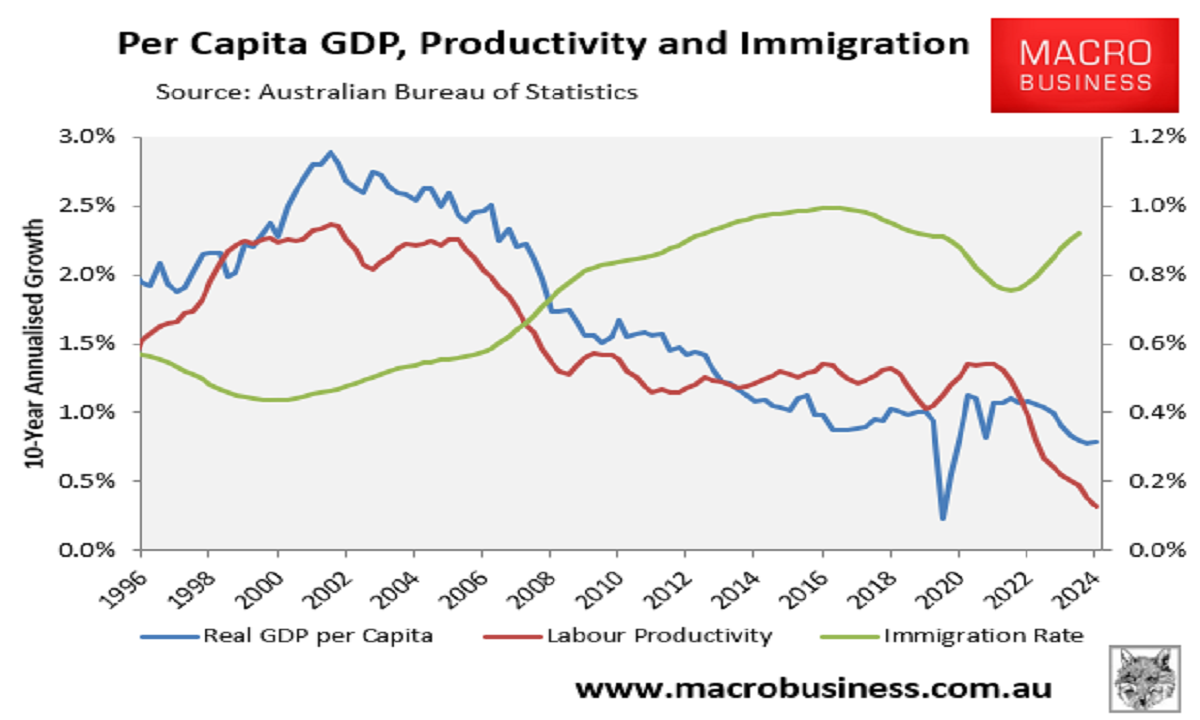

MacroBusiness, for years, has blamed much of Australia’s productivity slump on ‘capital shallowing’, which occurs when the nation’s population grows faster than business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

This situation leaves workers with less capital, resulting in less output per hour and a lower growth rate per capita.

As a stylised example, assume that you run a cafe with one coffee machine and two employees operating it, generating 100 coffees each hour.

If you double the number of people operating that machine, to four, your output will not quadruple. Because those four employees will have to wait for each other to finish brewing their coffees, they will bump into each other, causing congestion, etc.

Instead of generating 200 coffees per hour, which maintains your labour productivity, you’ll produce, say, 150 coffees per hour.

You have increased the number of people working while not increasing the capital stock—i.e., the number of coffee machines—to support them.

This means that you cannot make as many coffees per person, and your labour productivity has decreased.

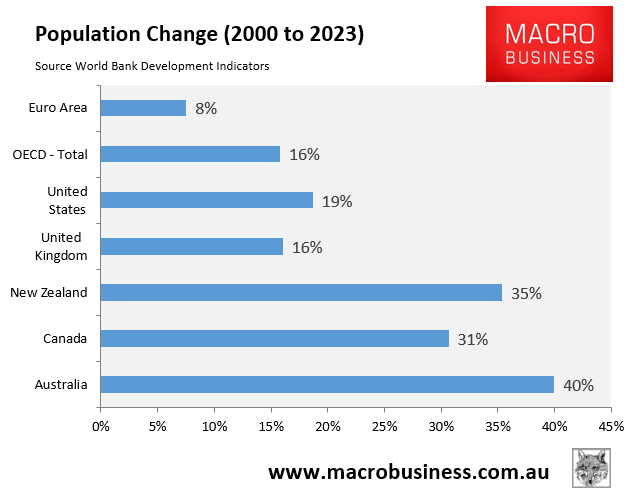

This is essentially what the Australian economy has gone through for the past two decades. Australia’s population growth has been the strongest in the advanced world, increasing by 8.7 million (46%) since 2000. However, we haven’t increased the infrastructure, business investment, or housing to support it.

As a result, Australia has experienced increases in congestion, less capital per worker, and, ultimately, slower productivity and per capita GDP growth.

A veritable conga line of economists and commentators have acknowledged that capital shallowing is a key driver of Australia’s productivity decline.

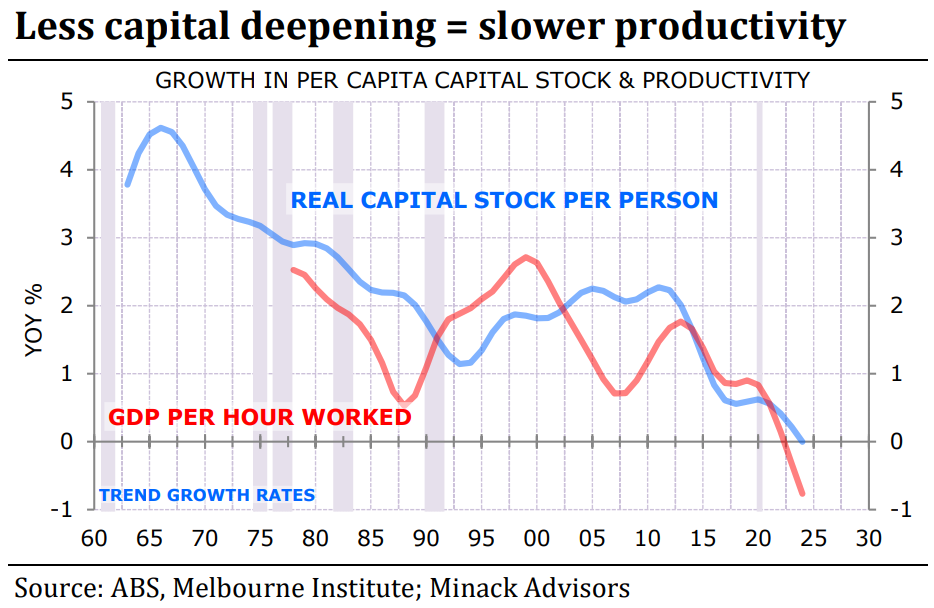

Gerard Minack, the former chief economist of Morgan Stanley who now runs his own advisory, explained the situation best.

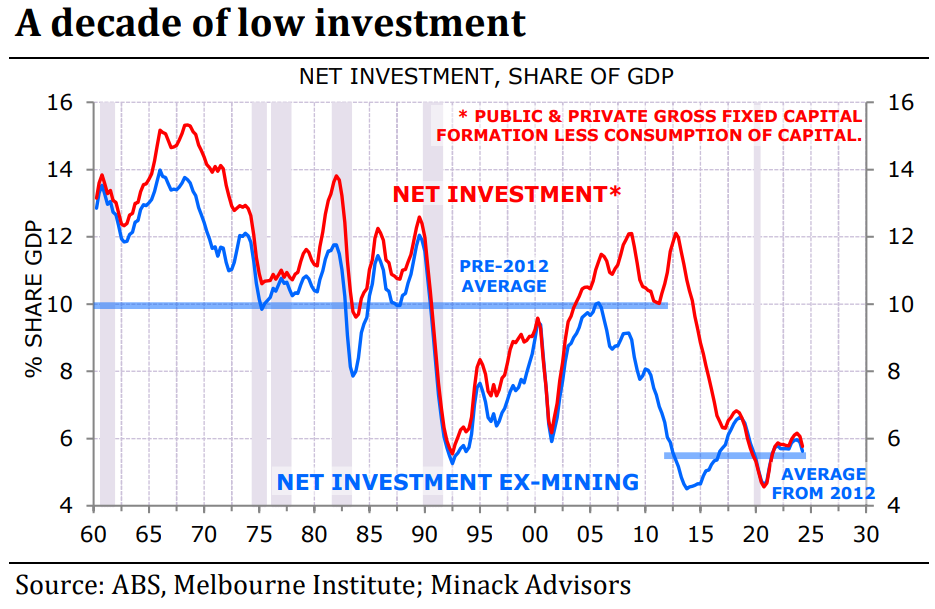

Minack explained that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

This “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

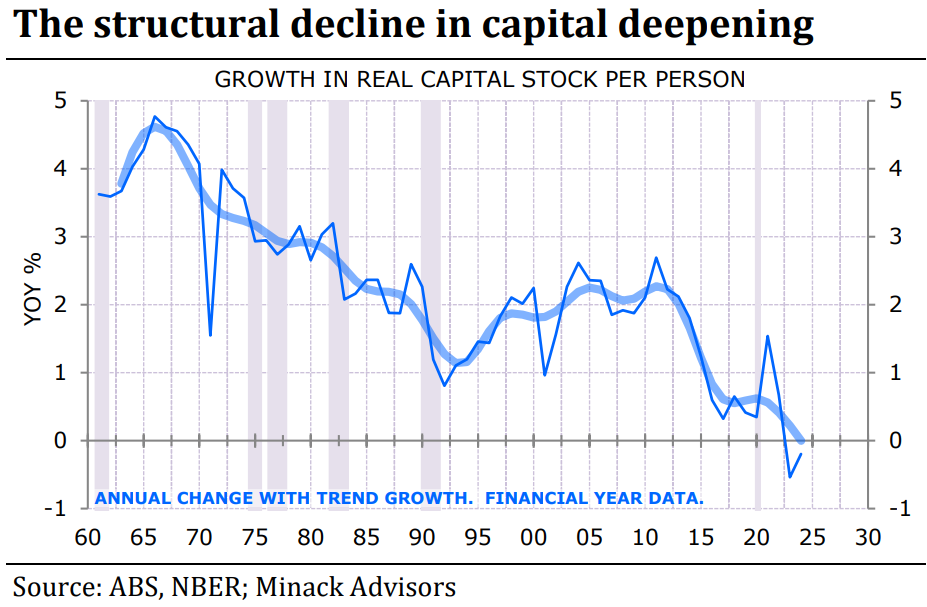

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

This month, former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry explained capital shallowing’s contribution to Australia’s productivity slump as follows:

[Capital deepening] makes each hour worked more productive, right?.. And capital deepening is obviously driven by having a rate of national investment that is matched to the rate of workforce growth, obviously, right? And so if your rate of workforce growth stays constant and your level of investment plummets, you’re going to suffer capital shallowing eventually.

And by the way, that is what Australia has suffered in the last 10 years, capital shallowing. It’s an extraordinary thing, capital shallowing, and it’s a consequence simply of the collapse in the investment rate. You experience capital deepening when the investment rate is sufficiently high relative to the rate of workforce growth, right? And that’s what Australia has experienced for most of the post-war, I mean post-World War II period, is capital deepening.

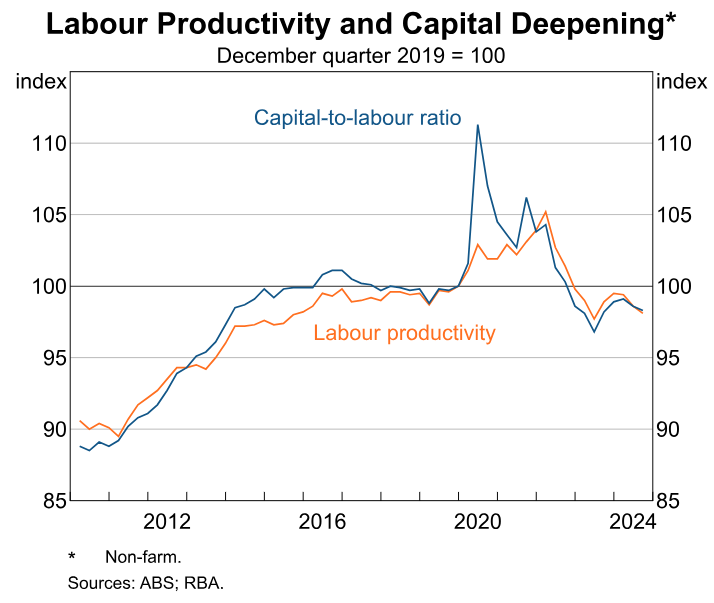

RBA’s Head of Economic Analysis, Michael Plumb, acknowledged in March that Australia’s mass immigration policy has eroded productivity through capital shallowing.

“The slow growth in labour productivity over recent years has reflected slow growth in both MFP and the amount of capital available to each worker”, Plumb said.

“Slow growth in the amount of capital available for each worker in the Australian economy—or a lack of ‘capital deepening’ – has contributed to slow growth in labour productivity”…

“In other words, overall investment has not kept pace with the strong employment growth”, Plumb said.

In a similar vein, former RBA governor Phil Lowe told The Australian Financial Review in April that capital shallowing was a key driver of Australia’s poor productivity growth:

But why has productivity stalled? Depressed business investment, says Lowe. Workers have less capital to work with, reducing how much they can produce from each hour they put in…

As the economy’s overall capital stock struggles to grow faster than it depreciates, the previous sharp growth in the ratio of capital to labour has flattened since 2015…

Policy-makers have mismanaged bringing in more people over the past decade. “We haven’t set up a climate to encourage business investment to build the capital stock for new workers,” says Lowe, particularly for housing…

Economics writer Ross Gittins explained Australia’s capital shallowing dilemma as follows:

If you get more people, but fail to provide them with the same capital equipment as the rest of us have – extra machines for the extra workers, extra houses for the extra families, and extra roads, public transport, schools and hospitals for the extra families – everyone’s standard of living goes down, not up.

In economists’ jargon, you have to ensure immigration doesn’t cause a decline in the “capital-to-labour ratio”. As well as the spending on “capital deepening” needed to raise our productivity, you also need spending on “capital widening” merely to stop our productivity worsening.

Guess what? We’ve had years of high immigration without the increased capital spending to go with it. Part of the problem is that the level of government with control over immigration, the feds, is not the level of government with responsibility for ensuring adequate additional investment in public infrastructure, the states.

Alan Kohler likewise questioned why politicians continue to run a high immigration policy when infrastructure, housing and business investment cannot keep up.

In 2025 the contribution of private business investment to GDP growth has fallen to zero; the growth in real capital stock per person is zero; real per capita income growth is zero; mining investment growth is zero; non-mining business investment growth has halved since Keating was treasurer…

The doubling of population growth from 1% to 2% a year is arguably essential to keep the place running as the birth rate declines, but it is causing profound structural changes in the economy because it is not matched by any serious planning for the extra people…

The cost of housing and over-burdened infrastructure and policing is sapping productivity while making life nasty and brutish…

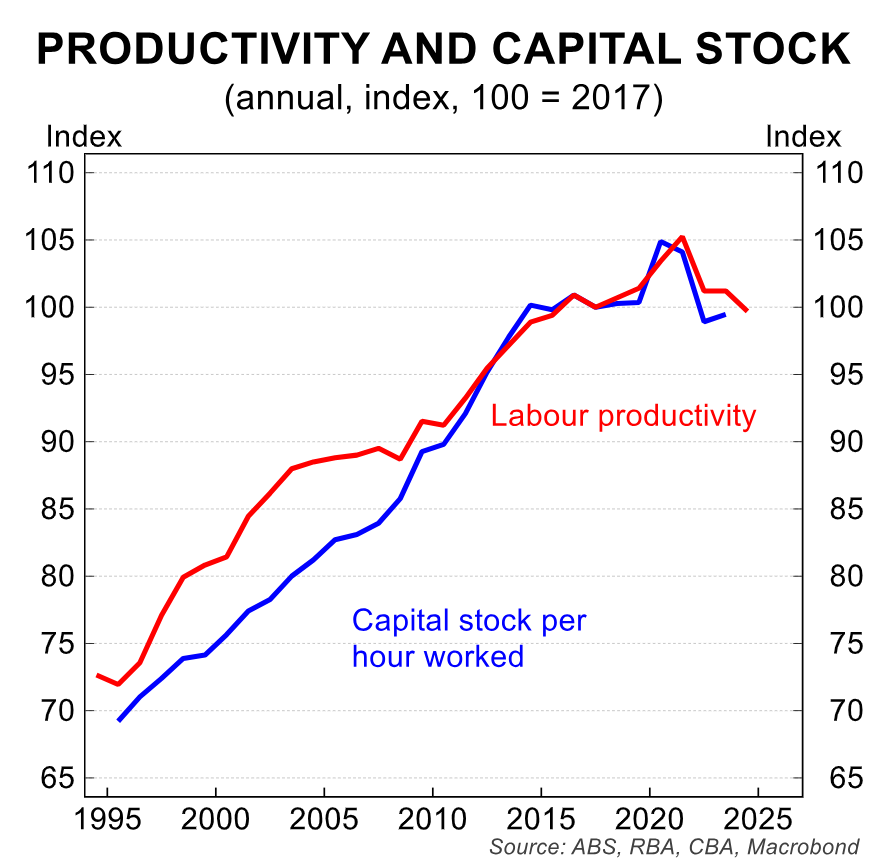

CBA economist Harry Ottley is the latest to acknowledge Australia’s serious capital shallowing problem, noting the following in his weekly update:

The Q1 2025 capex survey will be released next week. This is a key economic indicator due to the critical role business investment plays in driving productivity growth. Labour productivity in Australia has been notably weak in recent years; output per hour worked remains at its 2017 level.

Many factors contribute to weak productivity growth, including the structural shift in the Australian economy toward services—particularly the care economy. However, business investment remains low as a share of the economy, which has led to subdued growth in the capital stock.

This is happening at a time when Australia’s population and labour force are growing rapidly, resulting in less capital per hour worked.

Some of this picture is structural as services are much less capital intensive. Still, research suggests Australian firms are slow to adopt and invest in innovative technologies. Boosting business investment—and thus the capital stock—is key to improving productivity outcomes in Australia.

Australia’s economy will continue to shallow out:

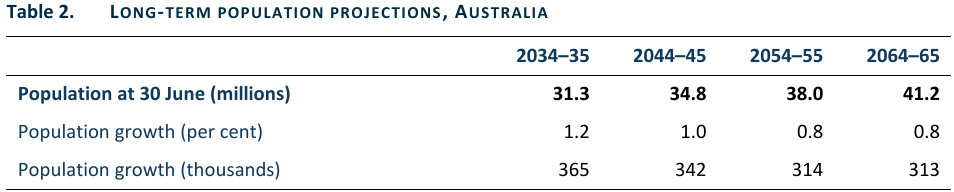

the 2024 Population Statement from Treasury’s Centre for Population, Australia’s population will increase by 13.5 million people in just 40 years.

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

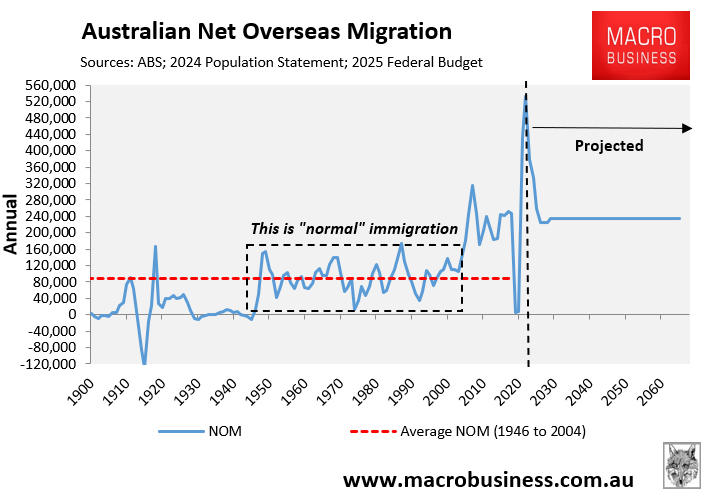

This 13.5 million projected population gain will be driven by high net overseas migration of 235,000 per year, which is more than double the average net migration of 90,000 recorded in the 60 years following World War II.

This 13.5 million population increase is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the country’s current population in just 40 years.

To sustain, let alone boost, current productivity growth, the housing, infrastructure, and business investment in these three large cities would have to be replicated in just 40 years. That is an impossible task.

As Australia’s population outpaces business, infrastructure, and housing investment, capital shallowing will persist, and productivity growth will stagnate.

Given that Australian economists have identified capital shallowing as a major cause of the country’s productivity collapse, they should advocate for limiting immigration to a level consistent with investment capacity.

Otherwise, Australia’s living standards will collapse.