Australia’s economy is an immigration-fed “basket case”

Alan Kohler published a stinging critique of the Australian economy, which he described as a “basket case”:

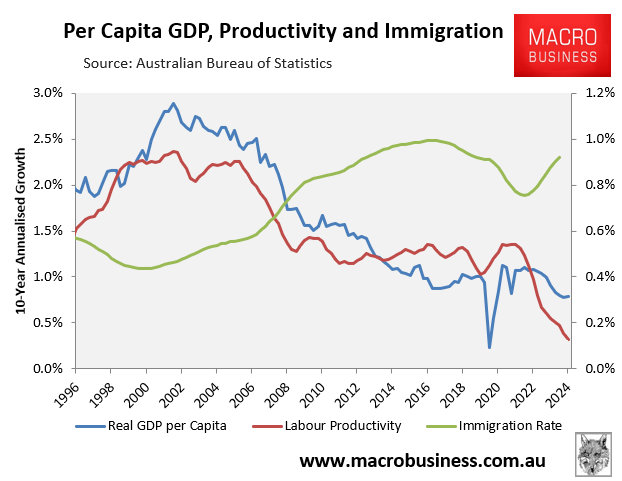

Productivity is declining and housing is unaffordable. Economic growth depends entirely on government spending and immigration, and high immigration has not been matched with enough infrastructure and housing to support it; as a result, Australia is divided, defensive, low tech and uncompetitive…

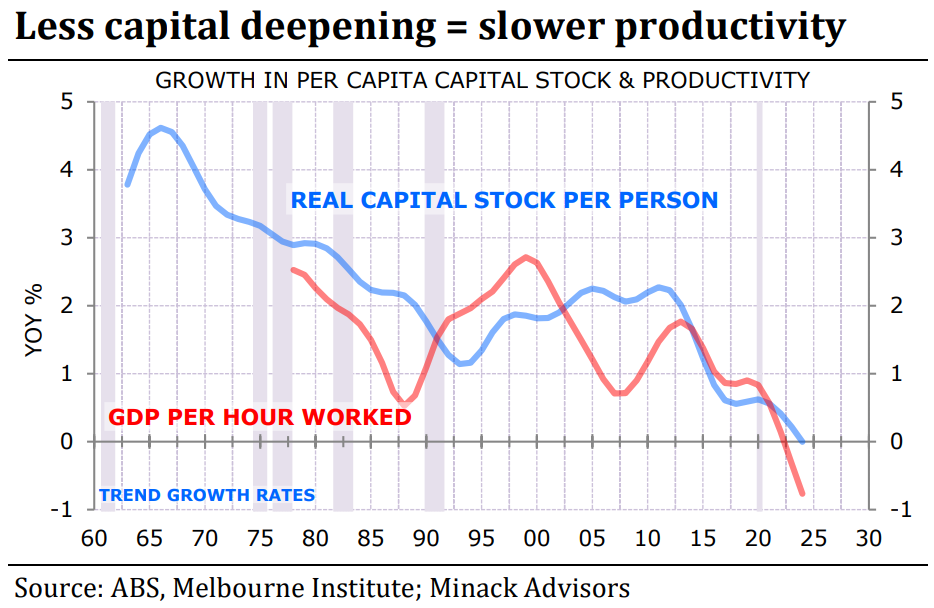

In 2025 the contribution of private business investment to GDP growth has fallen to zero; the growth in real capital stock per person is zero; real per capita income growth is zero; mining investment growth is zero; non-mining business investment growth has halved since Keating was treasurer; the housing debt to household income ratio is five times what it was in 1985; the average house now costs eight times the average income versus three times then…

The reason more government spending is needed is immigration.

The doubling of population growth from 1% to 2% a year is arguably essential to keep the place running as the birth rate declines, but it is causing profound structural changes in the economy because it is not matched by any serious planning for the extra people…

The cost of housing and over-burdened infrastructure and policing is sapping productivity while making life nasty and brutish…

The above is a sound critique by Kohler. A key driver of the Australian economy’s decline is ‘capital shallowing’, driven by record immigration without a corresponding increase in infrastructure and business investment.

The list of prominent economists identifying capital shallowing as a major cause of Australia’s productivity decline is growing.

First, consider the following testimony by former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry in the latest Joe Walker podcast:

Productivity’s got, I mean, there’s several ways of thinking about it, but the way I like to think about it, the easiest way to compartmentalise various components is it’s got two principal drivers.

The first being capital deepening—so just augmenting labour with capital assistance. And that could include AI assistance, right? And that makes each hour worked more productive, right? So that’s capital deepening. And capital deepening is obviously driven by having a rate of national investment that is matched to the rate of workforce growth, obviously, right? And so if your rate of workforce growth stays constant and your level of investment plummets, you’re going to suffer capital shallowing eventually.

And by the way, that is what Australia has suffered in the last 10 years, capital shallowing. It’s an extraordinary thing, capital shallowing, and it’s a consequence simply of the collapse in the investment rate. You experience capital deepening when the investment rate is sufficiently high relative to the rate of workforce growth, right? And that’s what Australia has experienced for most of the post-war, I mean post-World War II period, is capital deepening.

The other part of productivity growth, which we refer to as multifactor productivity growth, is probably better described as the stuff we don’t understand.

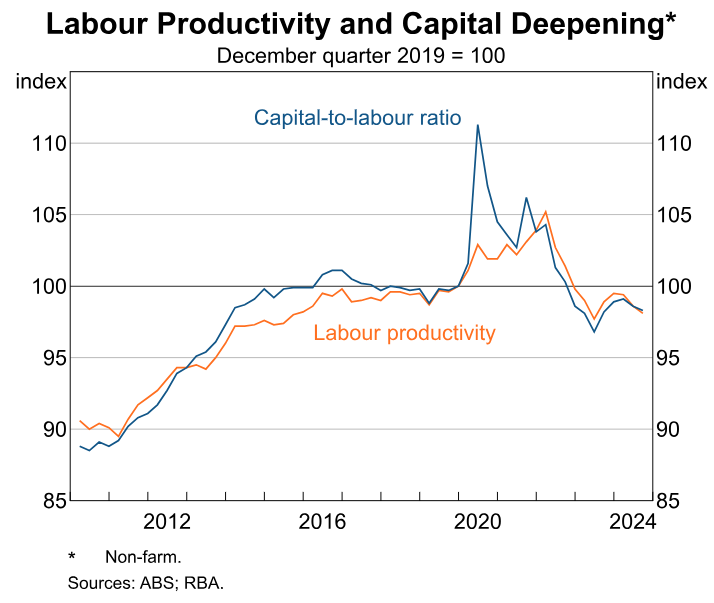

Second, RBA’s Head of Economic Analysis, Michael Plumb, acknowledged in March that Australia’s high immigration policy had eroded productivity through capital shallowing.

“The slow growth in labour productivity over recent years has reflected slow growth in both MFP and the amount of capital available to each worker”, Plumb said.

“Slow growth in the amount of capital available for each worker in the Australian economy—or a lack of ‘capital deepening’ – has contributed to slow growth in labour productivity”…

“In other words, overall investment has not kept pace with the strong employment growth”, Plumb said.

Third, former RBA governor Phil Lowe told The AFR last month that capital shallowings were a key driver of Australia’s sluggish productivity.

But why has productivity stalled? Depressed business investment, says Lowe. Workers have less capital to work with, reducing how much they can produce from each hour they put in…

As the economy’s overall capital stock struggles to grow faster than it depreciates, the previous sharp growth in the ratio of capital to labour has flattened since 2015…

Policy-makers have mismanaged bringing in more people over the past decade. “We haven’t set up a climate to encourage business investment to build the capital stock for new workers,” says Lowe, particularly for housing…

Fourth, Ross Gittins singled out persistently high immigration and capital shallowing as a driver of Australia’s productivity stagnation in March 2025:

“Almost to a person, economists are great believers in high rates of immigration. Immigration, they keep telling us, is great for economic growth. It’s true. There’s no easier way to grow an economy than to increase the number of people in it”…

“As all the economists were taught at uni but keep forgetting to mention to the punters, the claim that immigration raises our material standard of living – which is the oft-stated benefit of economic growth – comes with a big proviso”.

“Which is? Productivity. If you get more people, but fail to provide them with the same capital equipment as the rest of us have – extra machines for the extra workers, extra houses for the extra families, and extra roads, public transport, schools and hospitals for the extra families – everyone’s standard of living goes down, not up”.

“In economists’ jargon, you have to ensure immigration doesn’t cause a decline in the “capital-to-labour ratio”. As well as the spending on “capital deepening” needed to raise our productivity, you also need spending on “capital widening” merely to stop our productivity worsening”.

“Guess what? We’ve had years of high immigration without the increased capital spending to go with it. Part of the problem is that the level of government with control over immigration, the feds, is not the level of government with responsibility for ensuring adequate additional investment in public infrastructure, the states”.

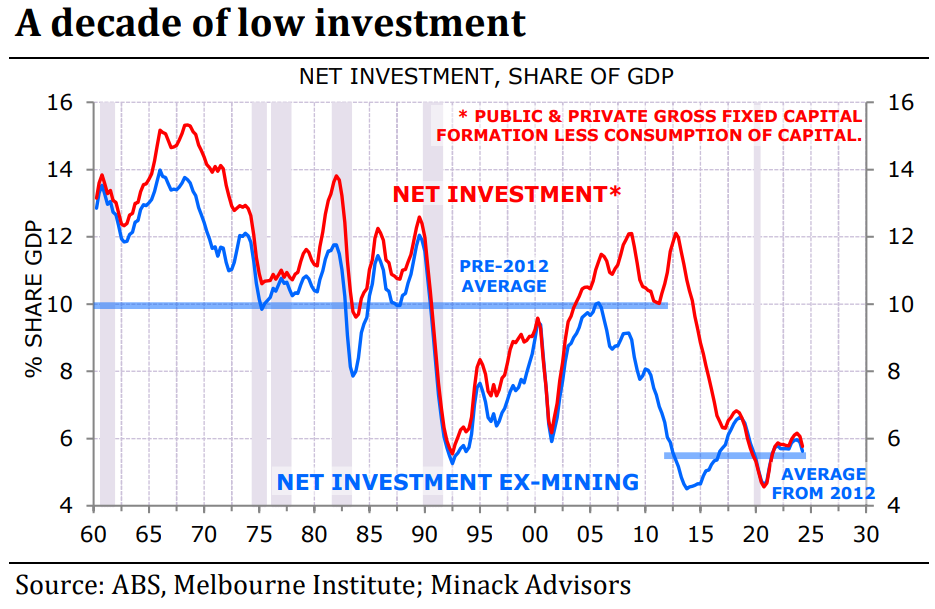

Finally, independent economist Gerard Minack expertly mapped Australia’s immigration-driven capital shallowing last year.

Minack explained that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

This “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

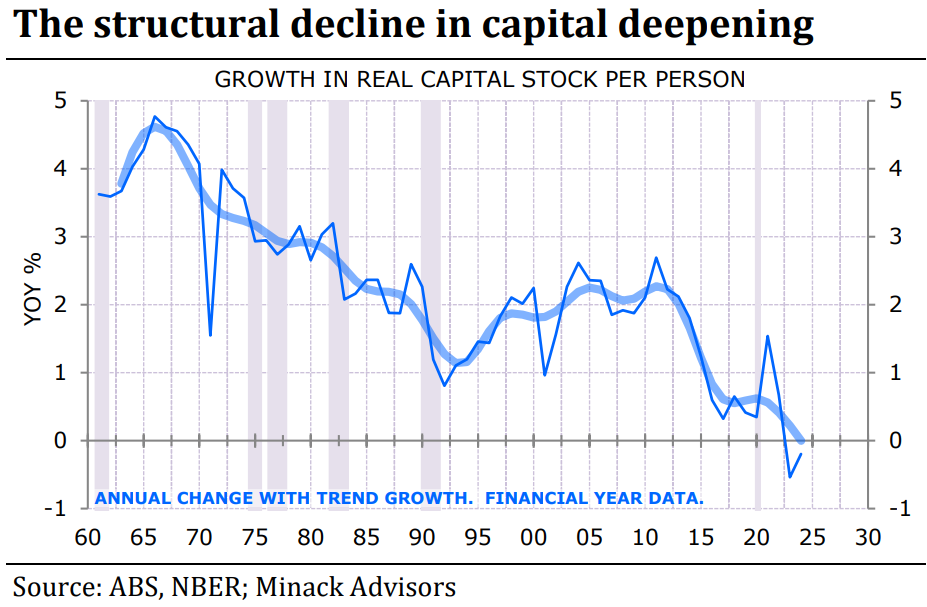

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

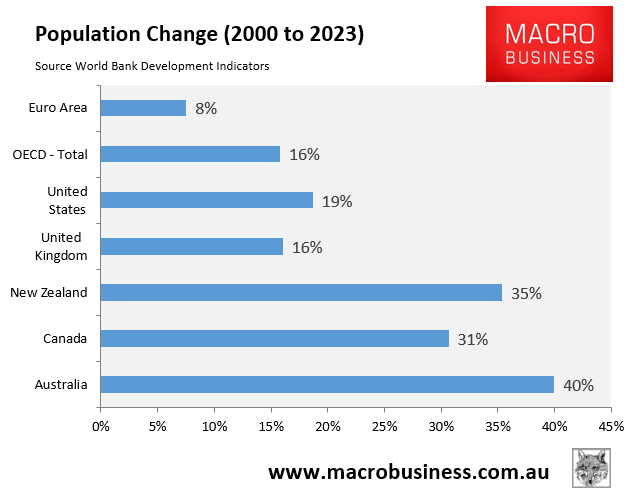

Australia experienced the fastest population growth in the advanced world between 2000 and 2023, as seen below.

The ABS Population Clock suggests that Australia’s population has risen by 8.7 million this century as of May 2025, a 46% increase.

It is little surprise, then, that Australia’s capital stock has failed to keep pace, resulting in poor productivity growth. The federal government’s excessive immigration program continually outpaces investments in business, infrastructure, and housing.

The long-term prospects for Australian productivity, therefore, remain bleak.

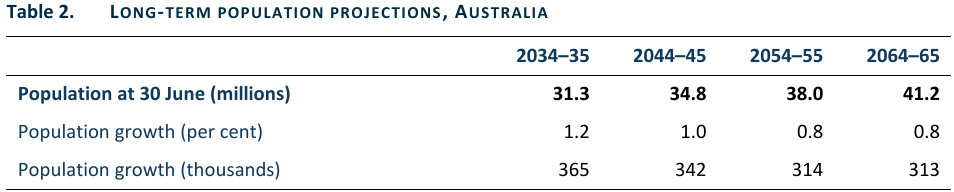

The 2024 Population Statement from Treasury’s Centre for Population projects that Australia will grow by 13.5 million people in just 40 years.

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

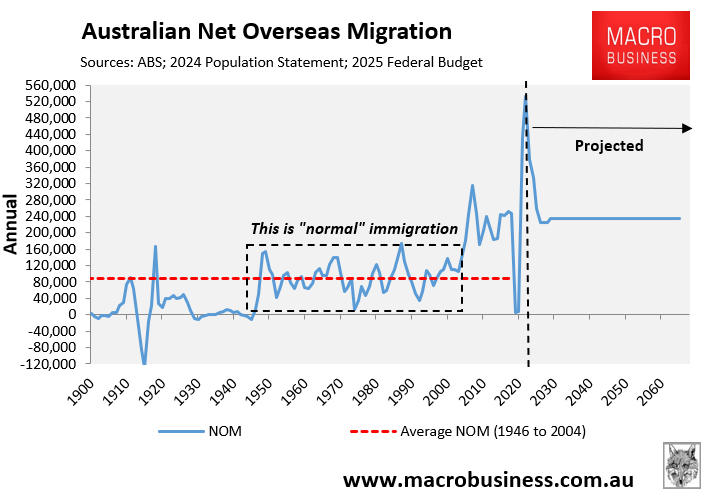

This anticipated 13.5 million population gain will be driven by a constant high net overseas migration of 235,000 per year, more than doubling the 90,000 average net migration in the 60 years after World War II.

This projected 13.5 million population increase is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the country’s current population in just 40 years.

To sustain, let alone boost, productivity growth, all of the housing, infrastructure, and business investment in these three large cities would have to be replicated in just 40 years. That’s an impossible task.

Instead, capital shallowing will continue, and productivity growth will remain stillborn, as the population outpaces business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

Given that Australia’s economists have identified capital shallowing as a key driver of Australia’s productivity slump, they should advocate cutting immigration to a level that is consistent with investment rates.

Otherwise, Australia’s productivity growth and living standards will forever languish.