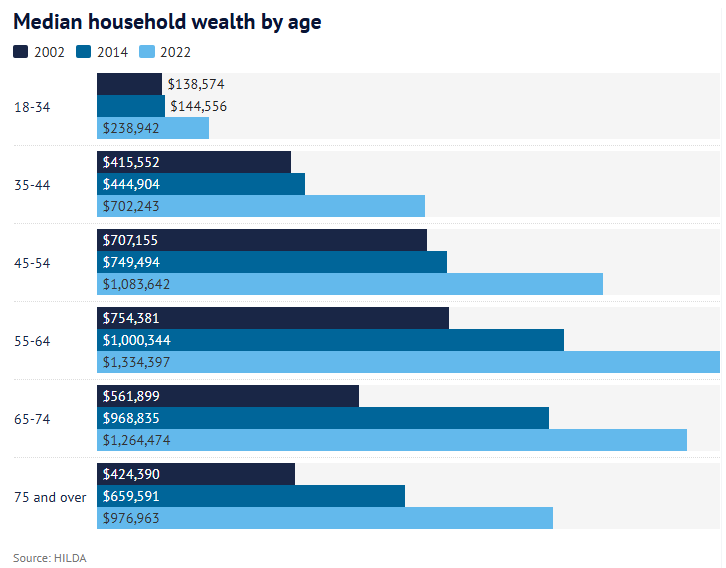

The most recent Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey from the University of Melbourne and the Melbourne Institute revealed a growing wealth discrepancy across the country.

As illustrated below, older Australians’ wealth has increased the most over the past two decades.

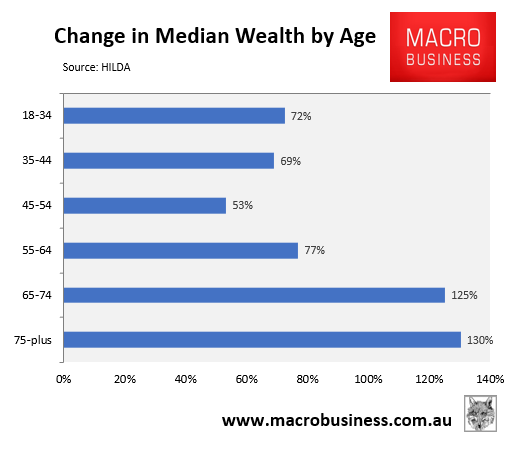

Australians aged 75 and over saw the greatest percentage rise in their wealth (+130%), followed by those aged 65 to 74 (+125%).

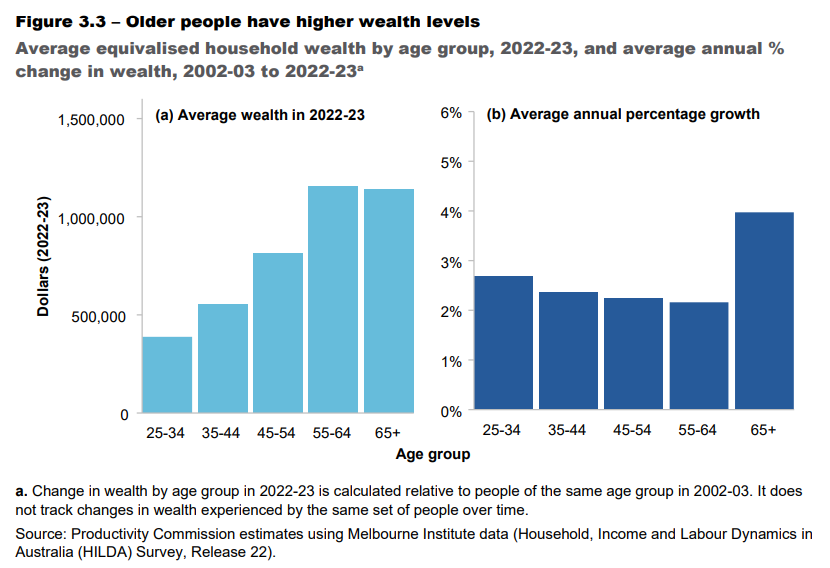

Separate data from the Productivity Commission (PC) also showed that wealth has grown most for older Australians aged 65 and over:

Seniors’ wealth increased at a compound rate of nearly 4% over the 20 years to 2022–23, more than doubling that of younger households.

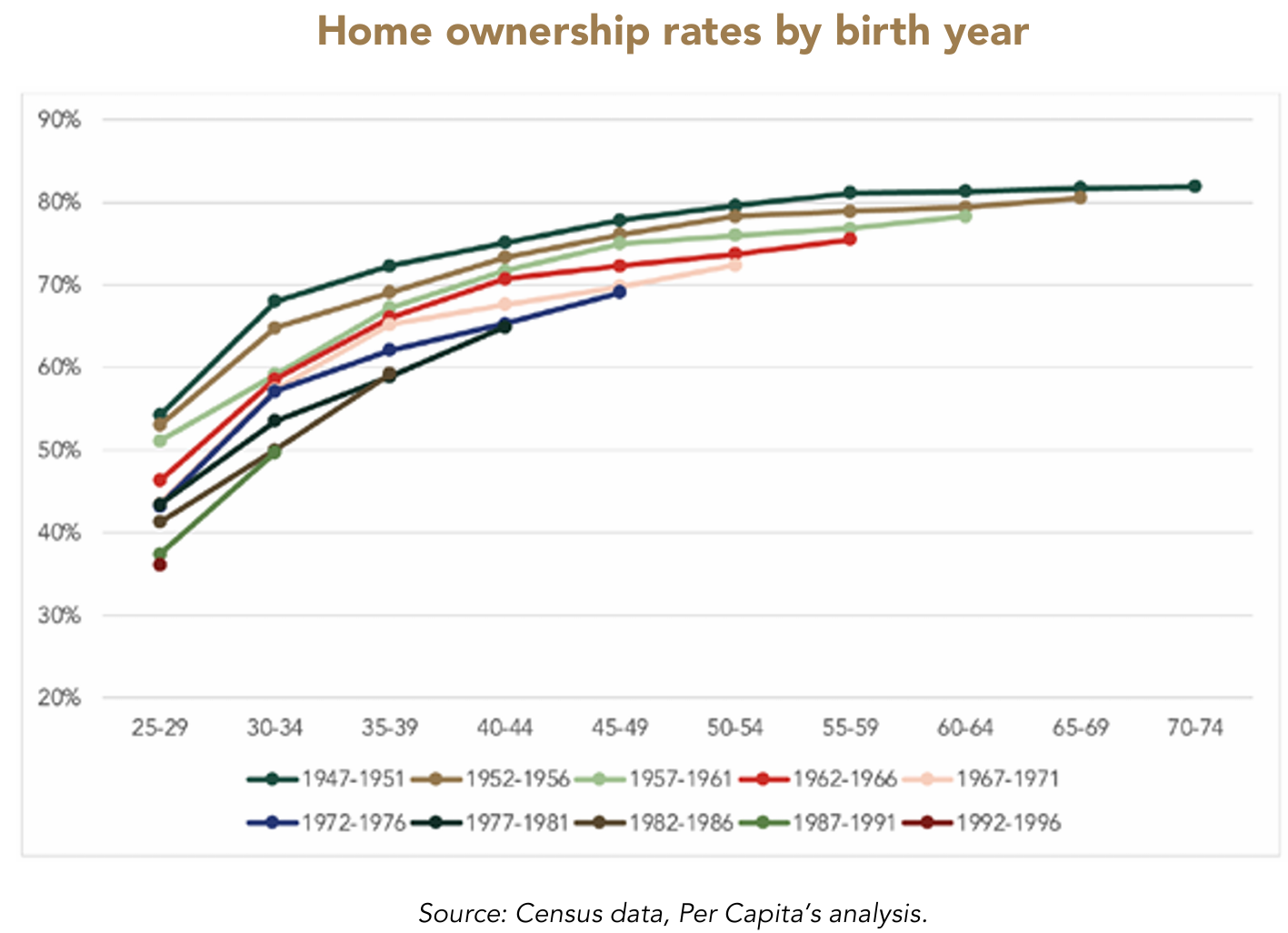

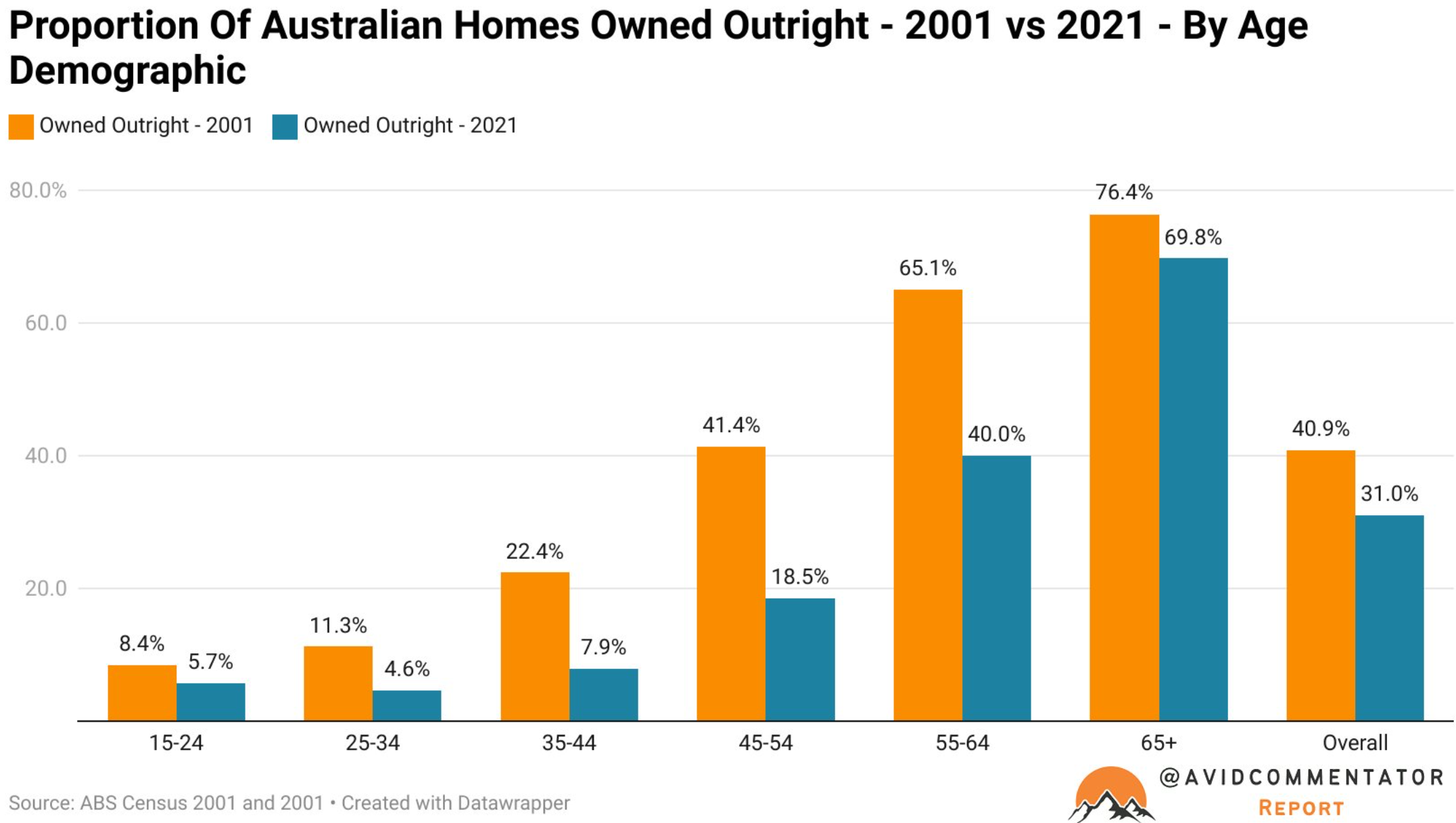

The growth in wealth among older Australians has been driven by rapid housing price appreciation, which has put home ownership out of reach for younger Australians.

The following chart shows that younger Australians have suffered the biggest decline in homeownership rates, while older Australian homeownership rates have remained relatively constant.

Younger Australians are also carrying larger mortgages for longer than earlier generations.

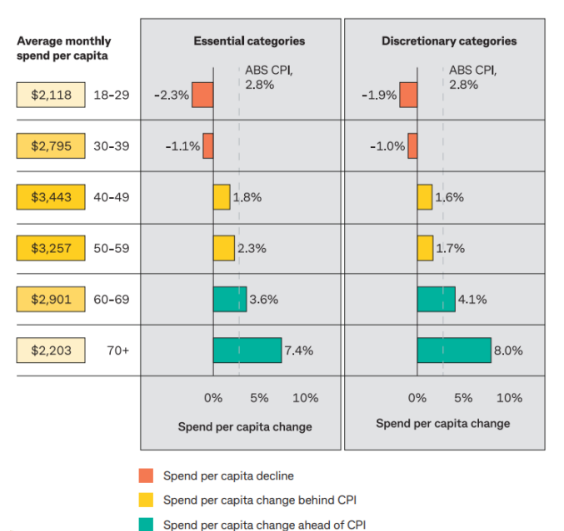

Most older households own their homes outright, meaning they have been relatively unaffected by rising rents and mortgage payments.

As a result, these households have spent more than other households since they have higher disposable income.

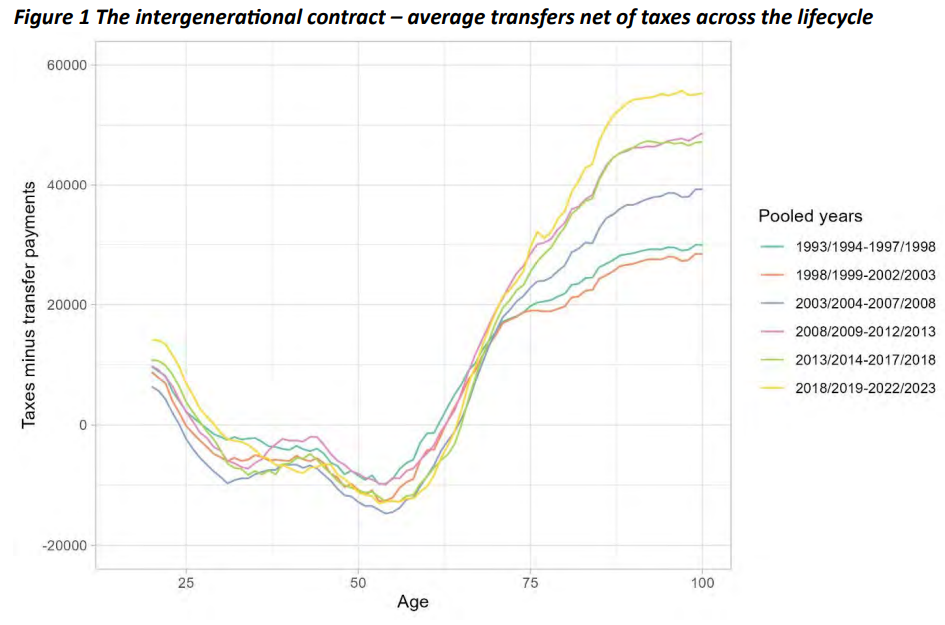

A new study from the ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy also shows that “Government expenditure targeting older Australians has increased significantly in real, per-person terms in recent decades”:

The tax and transfer system has become more generous to older Australians in recent decades. Government expenditure targeting older Australians – such as the age pension, aged care and health care – has increased significantly in real, per-person terms over this period. In contrast, net expenditure targeting younger households remains relatively constant. This is not a function of an ageing population, as we are measuring expenses per capita. The net mean impact of the Australian tax and transfer system on individuals of different ages is shown in Figure 1.

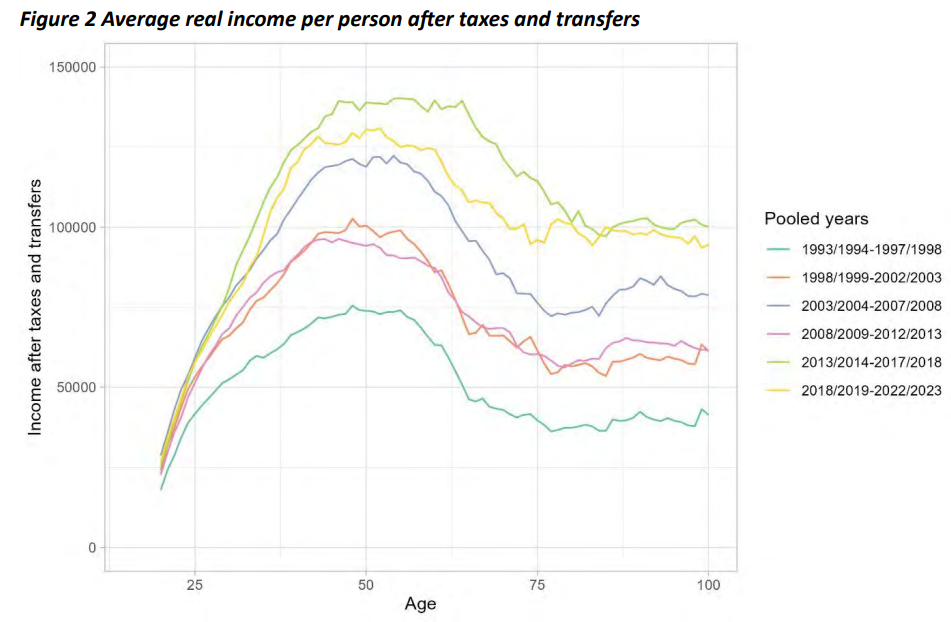

This increase in transfers to older Australians has occurred in a period in which older Australians have also earned significantly more private income, primarily as a result of higher capital income from real estate and superannuation.

The combination of these two trends has significantly changed the nature of the Australian tax and transfer system and the age profile of the final (after taxes and transfers) income distribution. In the first 10 years of our study (1993/94 to 2002/03), Australians aged over 60 had private income equal to 41% of the income of Australians aged 18-60 and average final income equal to 61% of the income of Australians aged 18-60. In the final ten years of our study, the pre-tax income of Australians aged over 60 was 65% of the population aged 18-60, and post-tax income is equal to 95% of their income.

This trend is even more notable when Australians over the age of 60 are compared to those aged 18- 30. In the past ten years, the older cohort has earned an income around 11 percent higher ($72,000 compared to $64,000 in 2022 dollars). However, the tax and transfer system means that the older group has an average after-tax income 60% higher than the younger group…

The paper reaches the following conclusions:

The tax and transfer system has not adjusted to the changing age profile of income in Australia. Current settings increasingly favour older Australians at the expense of younger Australians. Unless Australian society wants to explicitly favour older Australians, policies should be considered that reduce payments to older Australians and that shift the tax burden away from younger Australian and towards older Australians. Policy rules around means testing could be an important part of such a shift.

The Australian personal income tax system is levied on a base which captures only around two-thirds of household income, leaving income generated from owner-occupied housing and superannuation lightly taxed. This has important implications for efficiency and equity.

Growth in Australian land prices has created large transfers of wealth between generations of Australians. This price growth is driven to some extent by government policies, such as restrictive zoning and planning practices. Removing these barriers will deliver both equity and efficiency gains.

To achieve a fiscally sustainable budget over the coming decades, Australia must choose between increasing taxes and reducing government expenses. The consequences of this adjustment should be borne, at least in part, by older Australians. Achieving budget sustainability solely by increasing taxes on Australians of working age (mostly by growing personal income tax revenue through bracket creep) will worsen generational imbalance in the tax and transfer system.

As you can see, younger Australians have been sacrificed at the economic altar, with an intergenerational and inequality disaster unfolding over decades.