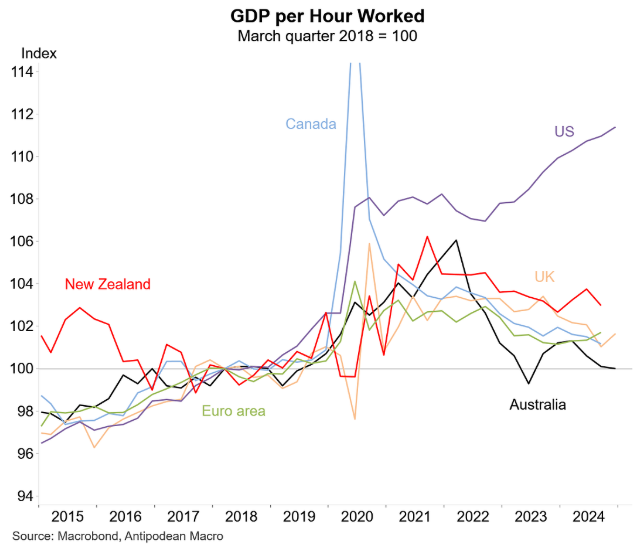

Australia’s productivity growth has averaged just 0.2% a year over the last decade.

Over the past decade, Australia’s productivity growth has been among the worst in the advanced world:

Labor’s first budget in 2022 included the assumption that productivity growth would average 1.2% over the long-term. The Coalition contends that annual GDP would be about $250 billion higher if productivity had grown at this pace, while annual tax revenue would have been $50 billion higher.

The Coalition has committed to a new productivity growth target of 1.5% annually if it wins the election on Saturday.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor said he is committed to “pursuing a rigorous productivity and investment enhancing reform agenda” if elected. “Productivity fuels our economic potential, yet under the Albanese Labor government it has collapsed”, he said.

A spokesperson for Treasurer Jim Chalmers said the government had “a big agenda to boost productivity, but we recognise that it will take more than one term to turn it around”.

“The decade to 2020 under the Coalition was the worst for productivity growth in 60 years”, the spokesperson said.

The causes of Australia’s productivity decline

There are five leading causes of Australia’s productivity decline.

Cause 1: The 2000s mining boom:

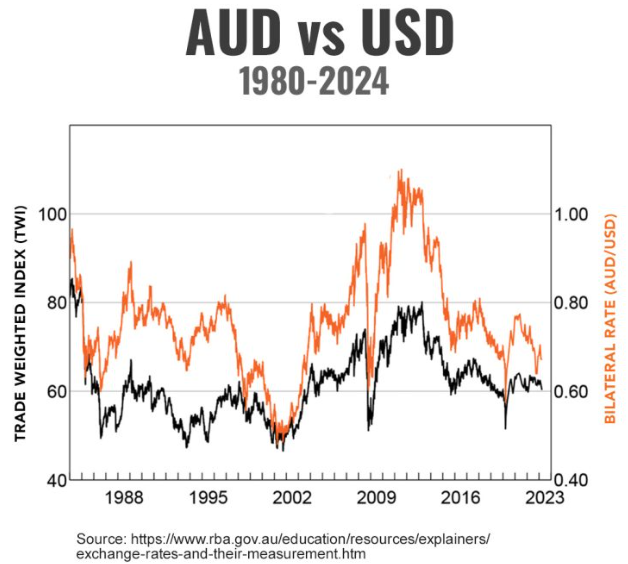

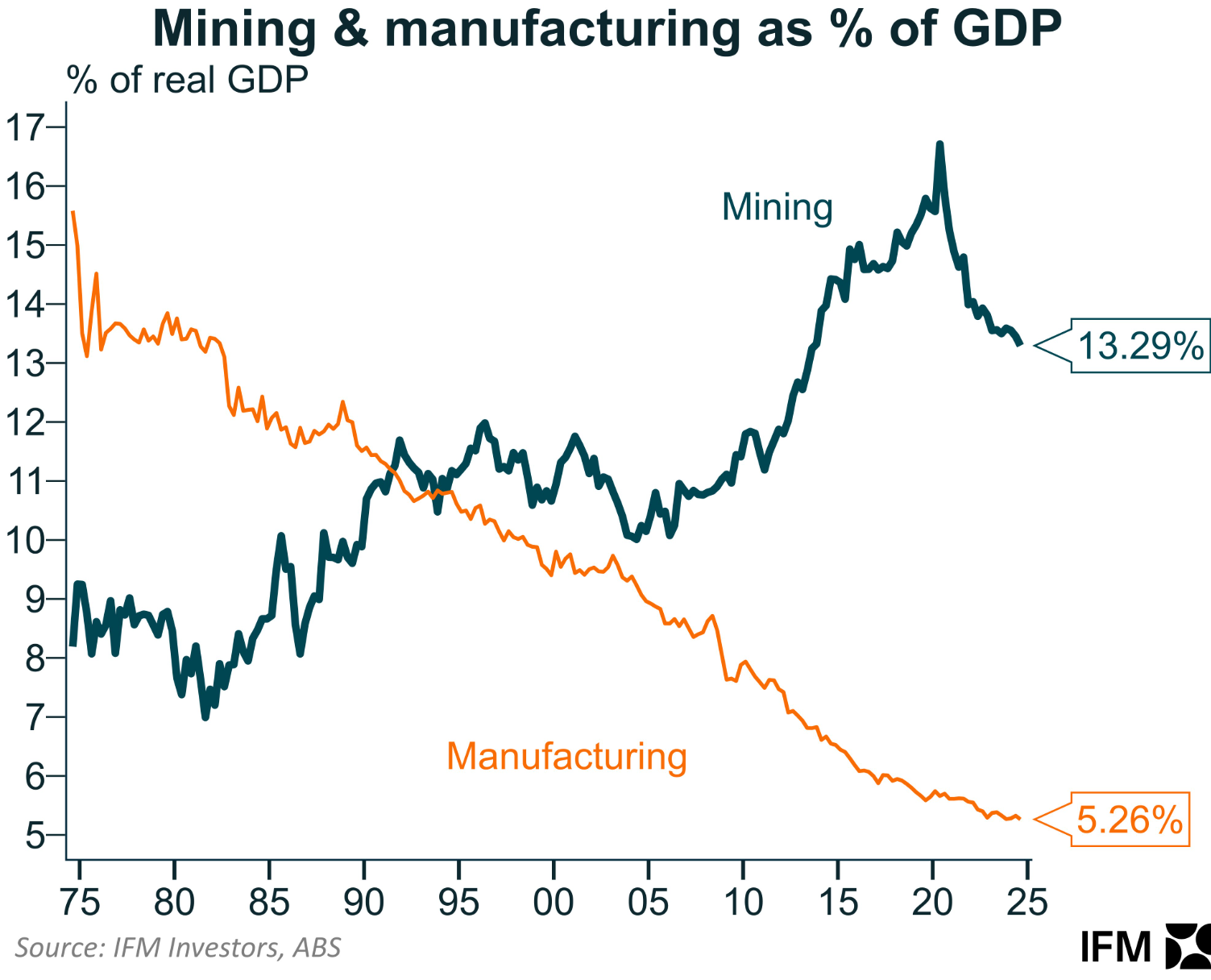

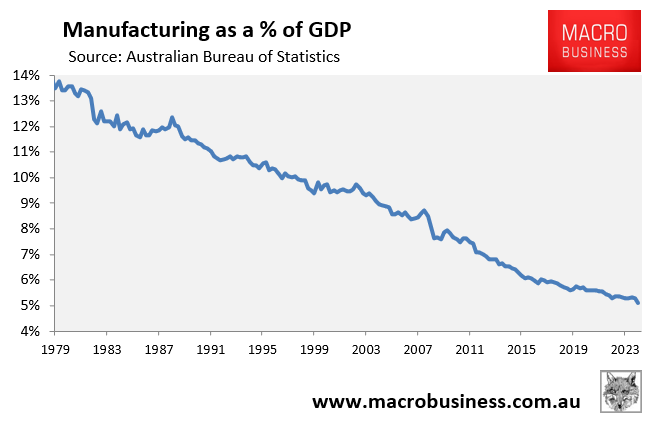

The inexorable increase in the Australian dollar following the start of the mining boom contributed to the contraction of Australia’s manufacturing sector, most notably in the automobile industry.

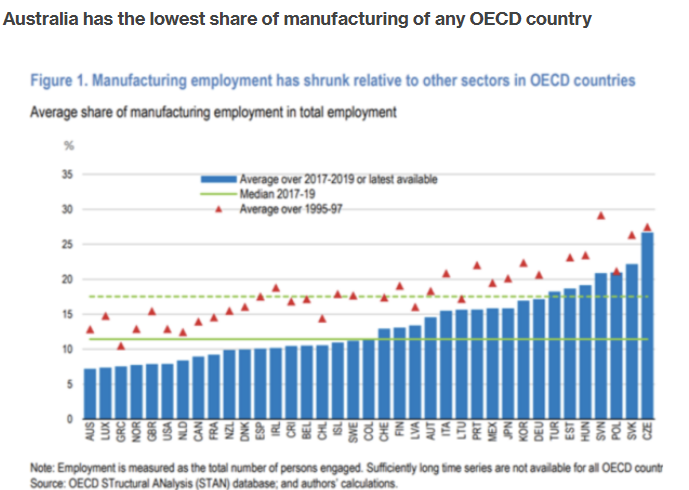

Manufacturing is susceptible to global competition and relies on capital investment and technological advancements. As a result, it has historically been the industry with the highest productivity increase.

Australia’s manufacturing sector has decreased to roughly 5% of GDP, the OECD’s lowest percentage, contributing to the country’s poor productivity growth.

Cause 2: Record immigration:

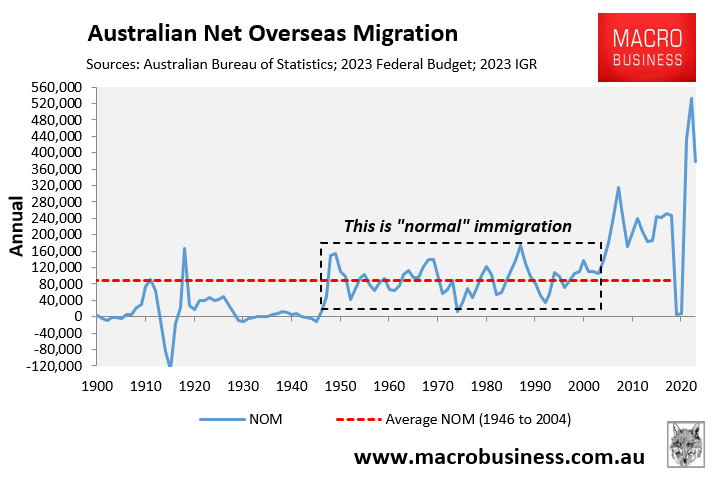

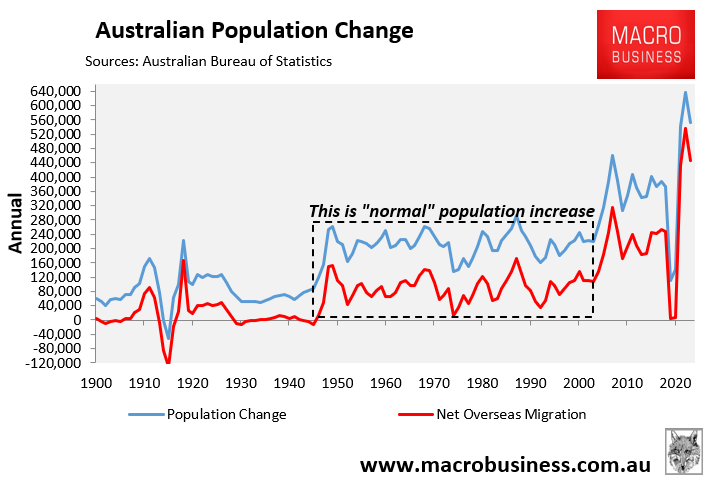

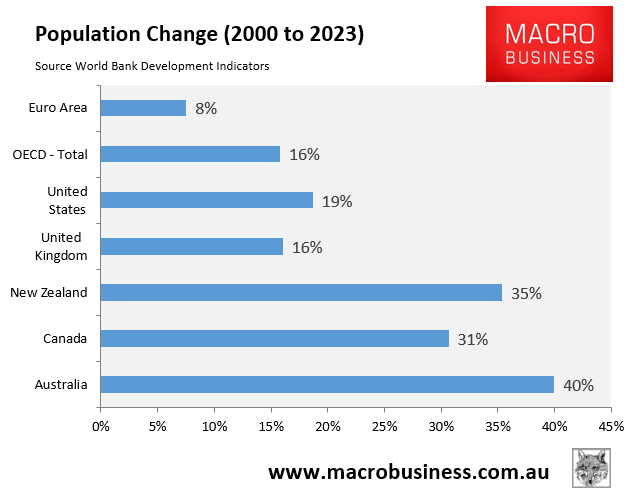

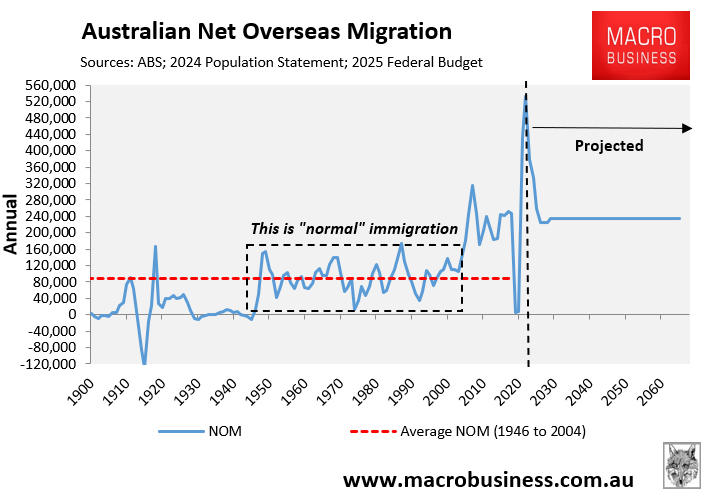

The federal government massively increased net overseas migration in the mid-2000s.

As a result, Australia’s population expanded much faster than business, housing, and infrastructure investment, leaving workers with less capital.

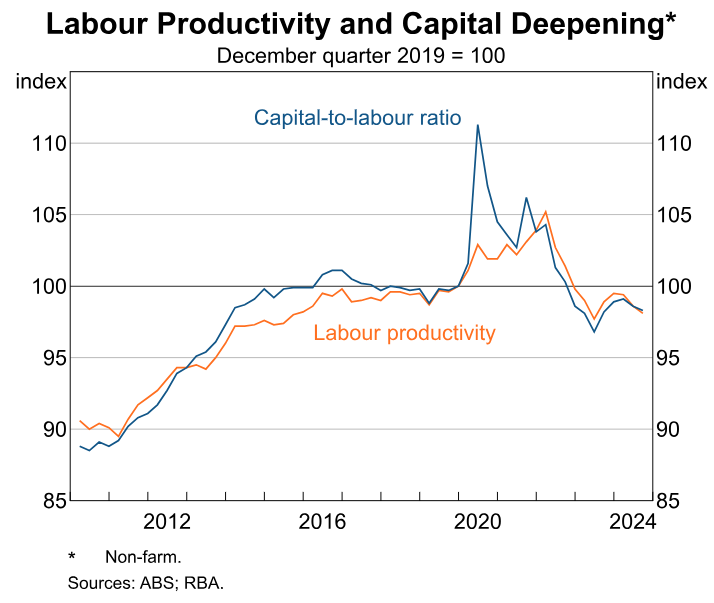

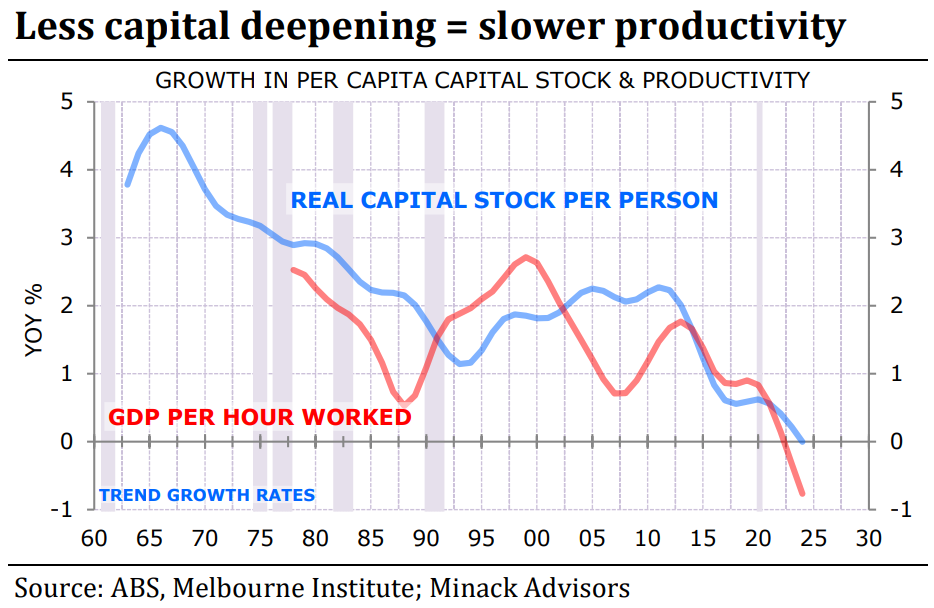

In March 2025, the RBA’s Head of Economic Analysis, Michael Plumb, acknowledged that Australia’s high immigration policy had eroded productivity through ‘capital shallowing’.

“The slow growth in labour productivity over recent years has reflected slow growth in both MFP and the amount of capital available to each worker”, Plumb said.

“Slow growth in the amount of capital available for each worker in the Australian economy – or a lack of ‘capital deepening’ – has contributed to slow growth in labour productivity”…

“In other words, overall investment has not kept pace with the strong growth in employment”, Plumb said.

Last month, former RBA governor Phil Lowe told The AFR that capital shallowing is a key factor behind Australia’s sluggish productivity.

But why has productivity stalled? Depressed business investment, says Lowe. Workers have less capital to work with, reducing how much they can produce from each hour they put in…

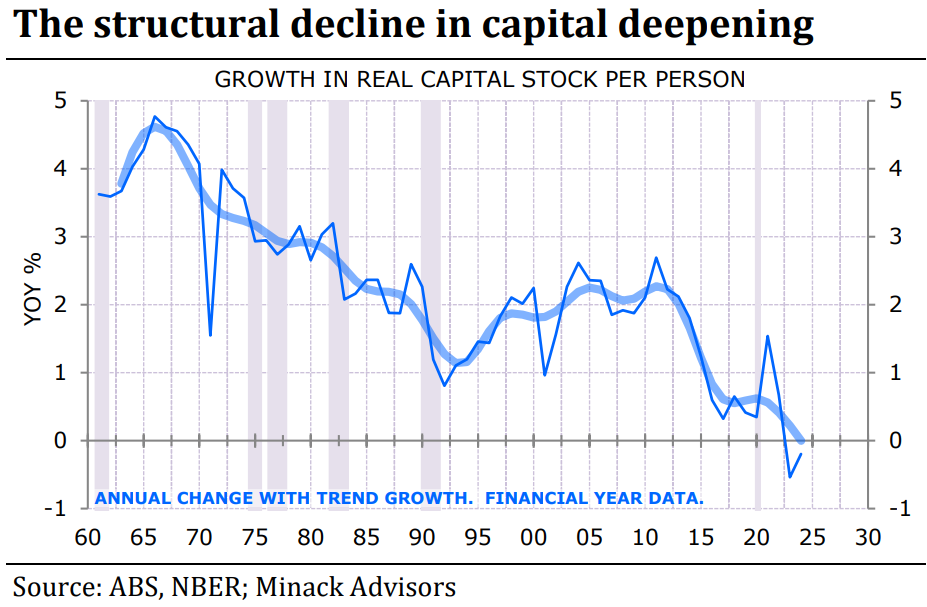

As the economy’s overall capital stock struggles to grow faster than it depreciates, the previous sharp growth in the ratio of capital to labour has flattened since 2015…

Policy-makers have mismanaged bringing in more people over the past decade. “We haven’t set up a climate to encourage business investment to build the capital stock for new workers,” says Lowe, particularly for housing…

Ross Gittins has also recently singled out persistently high immigration as a driver of Australia’s productivity stagnation:

“Almost to a person, economists are great believers in high rates of immigration. Immigration, they keep telling us, is great for economic growth. It’s true. There’s no easier way to grow an economy than to increase the number of people in it”…

“As all the economists were taught at uni but keep forgetting to mention to the punters, the claim that immigration raises our material standard of living – which is the oft-stated benefit of economic growth – comes with a big proviso”.

“Which is? Productivity. If you get more people, but fail to provide them with the same capital equipment as the rest of us have – extra machines for the extra workers, extra houses for the extra families, and extra roads, public transport, schools and hospitals for the extra families – everyone’s standard of living goes down, not up”.

“In economists’ jargon, you have to ensure immigration doesn’t cause a decline in the “capital-to-labour ratio”. As well as the spending on “capital deepening” needed to raise our productivity, you also need spending on “capital widening” merely to stop our productivity worsening”.

“Guess what? We’ve had years of high immigration without the increased capital spending to go with it. Part of the problem is that the level of government with control over immigration, the feds, is not the level of government with responsibility for ensuring adequate additional investment in public infrastructure, the states”.

Independent economist Gerard Minack expertly explained Australia’s immigration-productivity conundrum last year.

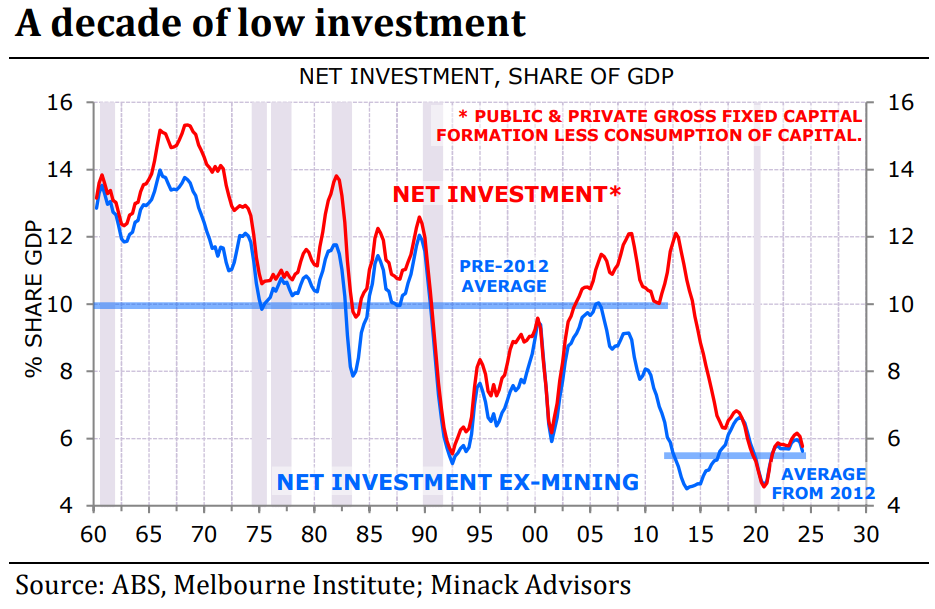

Minack noted that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

This “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

Australia experienced the advanced world’s fastest population increase between 2000 and 2023, growing by 40%.

Little wonder, then, that Australia’s capital stock has failed to keep pace, lowering productivity growth.

Australia is caught in a productivity trap because the federal government has operated a permanently high migration program over business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

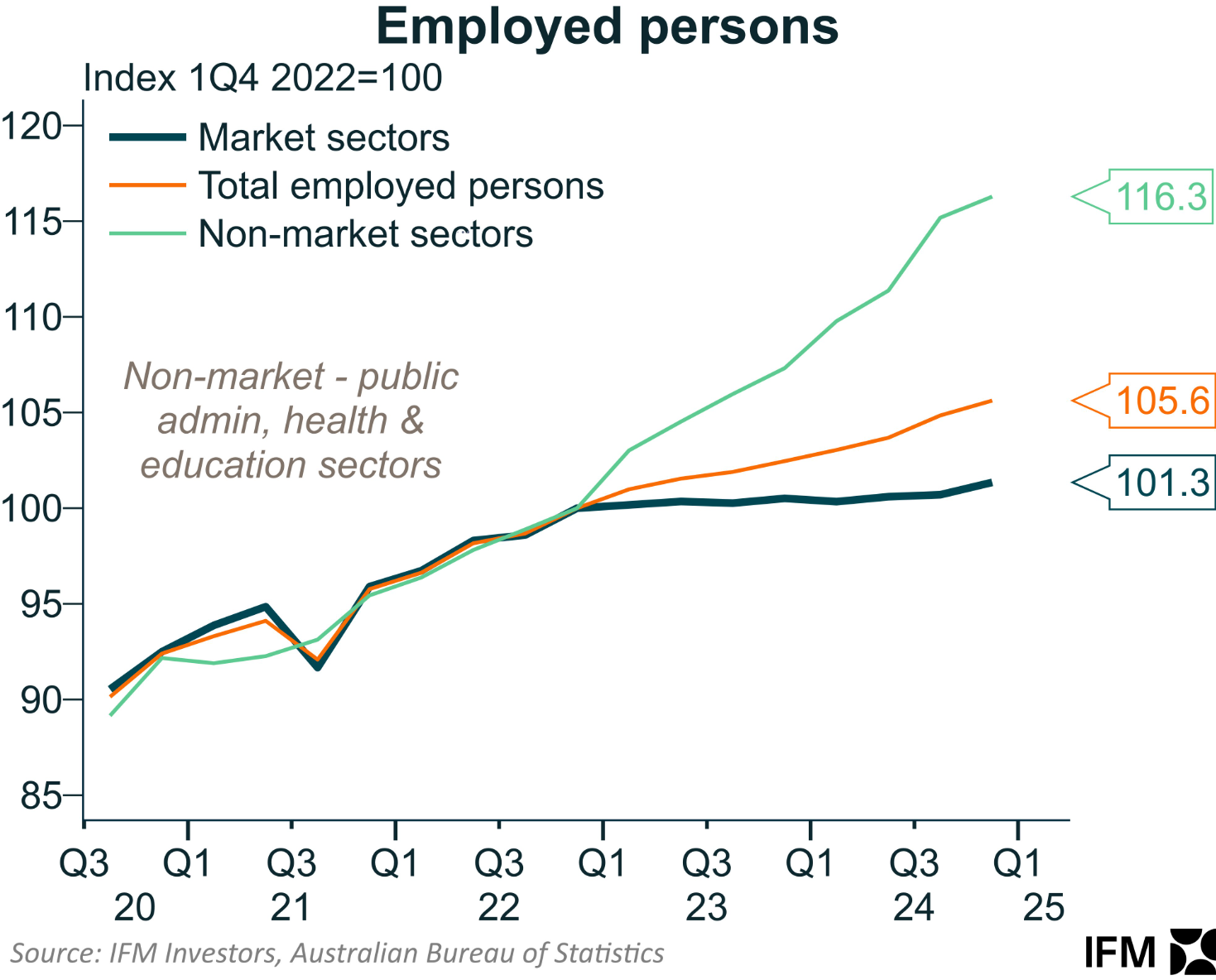

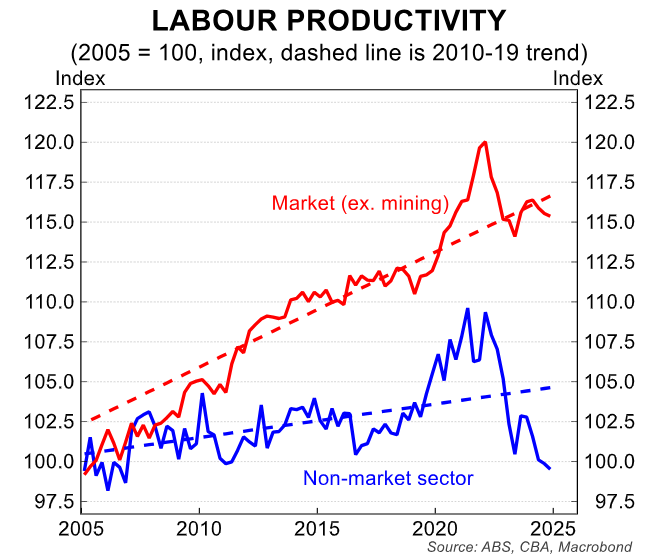

Cause 3: Explosive growth in the non-market economy:

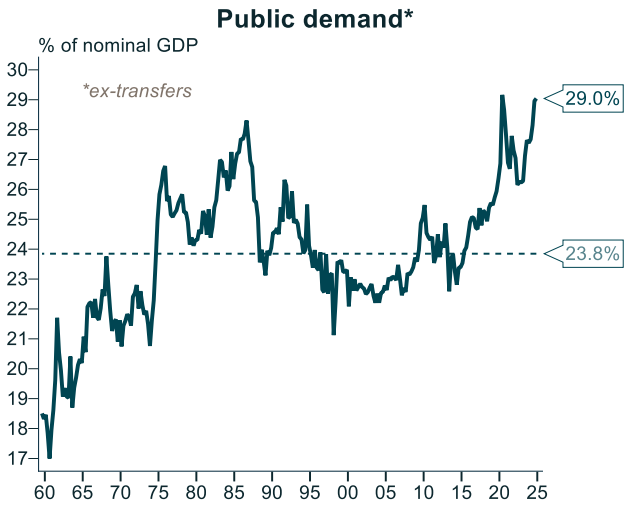

Excessive government spending, which rose to a record 29% of GDP in Q4 2024, is the third driver of Australia’s productivity stagnation.

Much of this public spending has been channelled into low-productivity non-market (government-aligned) jobs, which have expanded at a furious pace and crowded out the market sector.

Cause 4: Soaring energy costs:

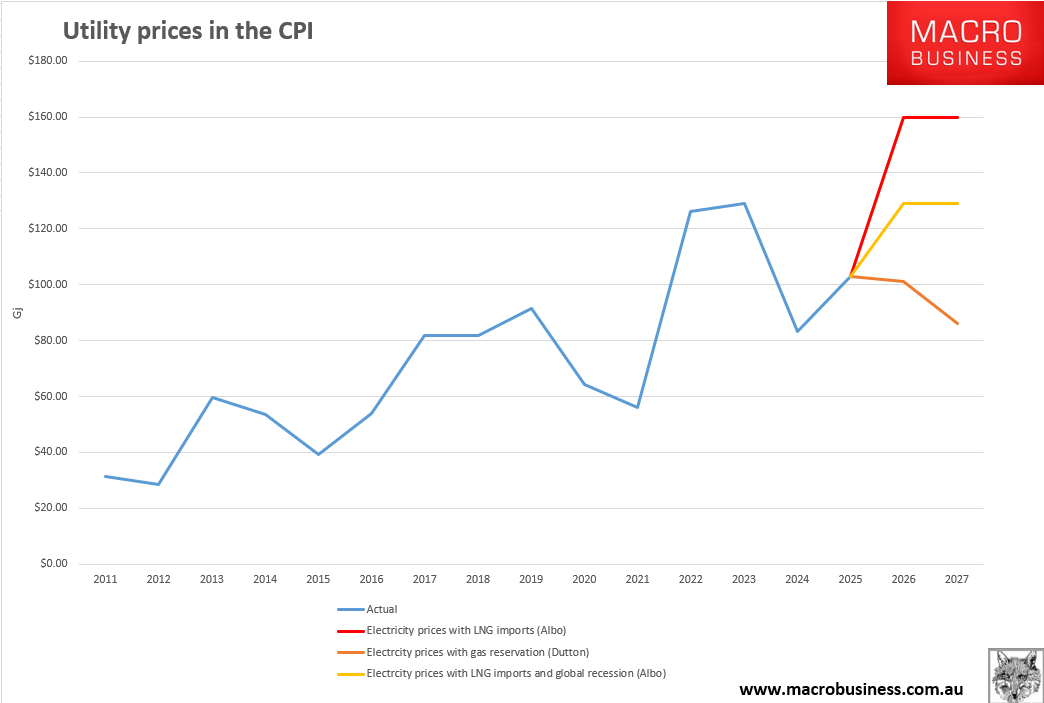

The fourth reason driving Australia’s productivity decline is linked to the first: rising energy costs.

The structural rise in Australian energy costs—gas and electricity—has helped to shrink the manufacturing sector, hollowing out the economy, reducing economic complexity, and eroding productivity.

Australia’s manufacturing economy can only be sustained with cheap and reliable electricity.

Despite being one of the world’s largest energy exporters, Australia’s energy advantage has been destroyed by the failure to secure East Coast gas supplies and the abandonment of historically cheap and reliable baseload power for intermittent and expensive renewables.

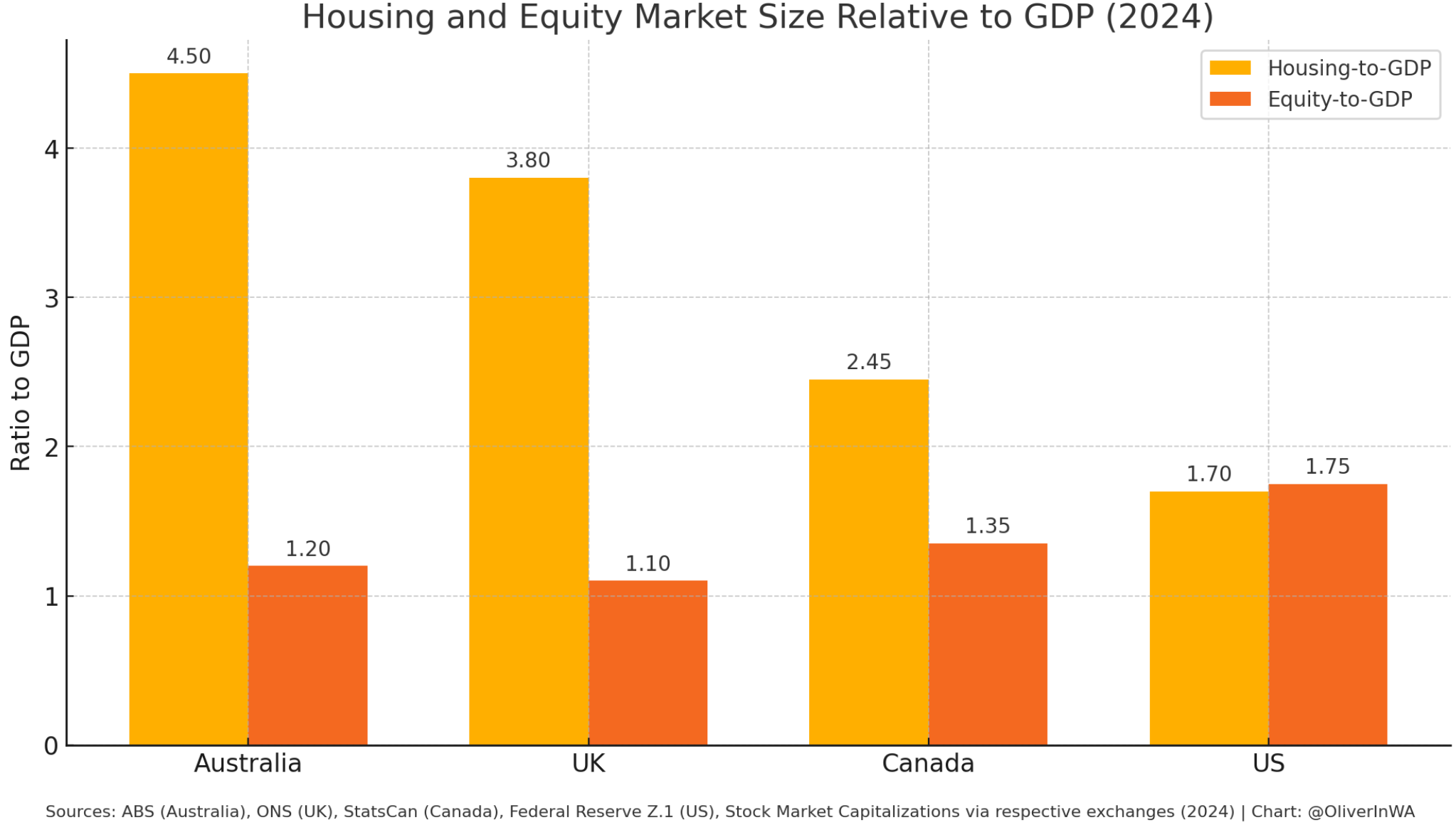

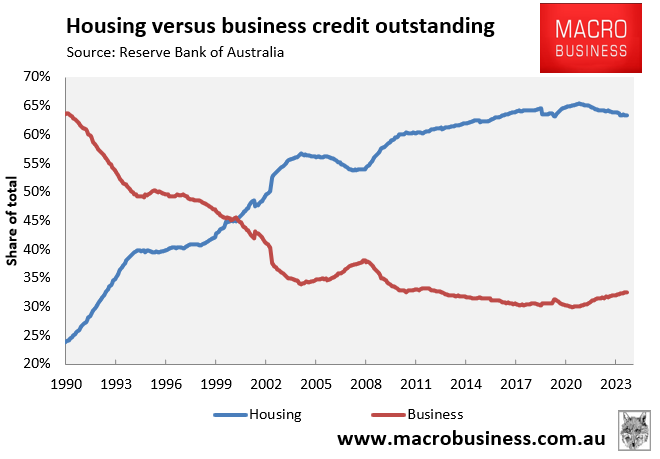

Cause 5: Poor tax policies encouraging housing speculation over productive investment:

Australia taxes productive effort too hard and undertaxes efficient sources like resources and land.

We also provide tax incentives to speculate on residential property.

The end result is that Australia has channelled significant sums of capital into non-productive housing:

In the process, Australia has starved investment into productive businesses:

“All we’ve done is pour all of this money into houses, which has deprived the economy of heaps and heaps of productive capital”, AustralianSuper chief executive Paul Schroder told The AFR Business Summit in March.

“We’ve got all this money in domestic houses and we’re not backing business, we’re not creating new things, we’re not driving productivity”…

“I think the big, burning productivity and cost of living problem is housing. I think we keep underestimating how worrying housing is”, Schroder said.

Australia’s productivity outlook is poor:

The longer-term outlook for Australian productivity growth remains poor.

First, capital shallowing is set to continue as Australia’s population grows faster than business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

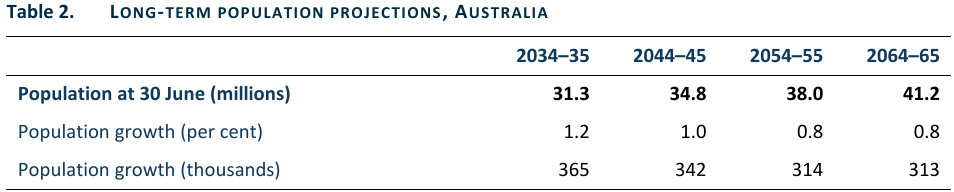

The 2024 Population Statement from Treasury’s Centre for Population projects that Australia’s population will balloon by 13.5 million people in only 40 years:

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

This 13.5 million projected population increase will be driven by permanently high net overseas migration of 235,000 annually, more than double the 90,000 average net migration in the 60 years following World War II.

This 13.5 million projected population increase is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the nation’s current population in only 40 years.

The housing, infrastructure, and business investment in these three major cities would need to be replicated in only 40 years to maintain current productivity growth, let alone increase it. That is an impossible task.

Second, the Albanese government has refused to emulate the Coalition’s east coast gas reservation policy and has committed to replacing traditional baseload electricity generation with expensive and intermittent renewables.

As a result, LNG imports are expected to commence at the end of this year or early next year, which will likely send the east coast gas price to $20 per gigajoule or more, from around $12.

LNG imports will become the marginal price setter for the East Coast electricity while energy rebates roll off.

Inflation will rise, cost-of-living pressures will persist, and Australia will continue deindustrialising as it becomes too expensive to make anything here, resulting in a less diversified and productive economy.

Finally, the Albanese government has committed to leveraging the federal budget to drive more capital into housing.

Labor has promised to effectively create a state-sponsored subprime mortgage scheme by allowing all first-time home buyers to purchase a property with a 5% down payment, with the government (taxpayers) guaranteeing 15% of the borrowers’ loan.

Labor has also stated that mortgage lenders will no longer be required to include student debts in their serviceability assessments.

In short, the Australian economy is stuck in a productivity death spiral.