Australia has a graduate visa problem

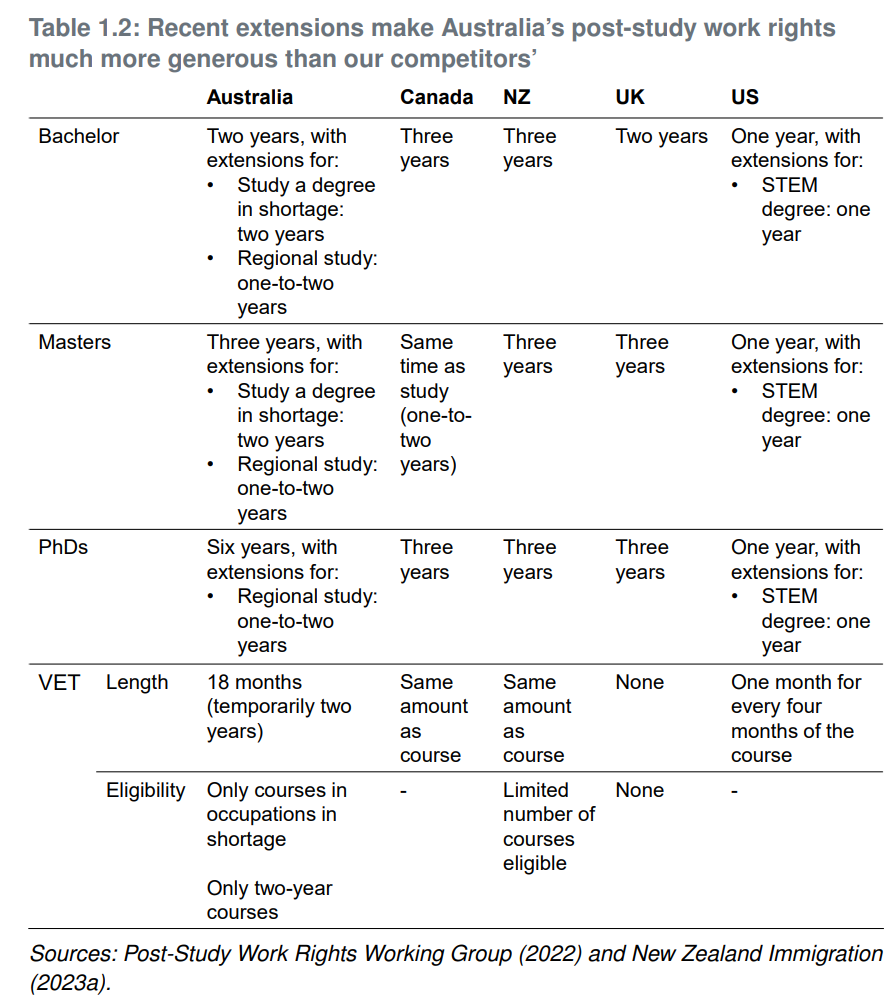

Australia has some of the most generous post-study work rights for overseas students, as shown in the table below.

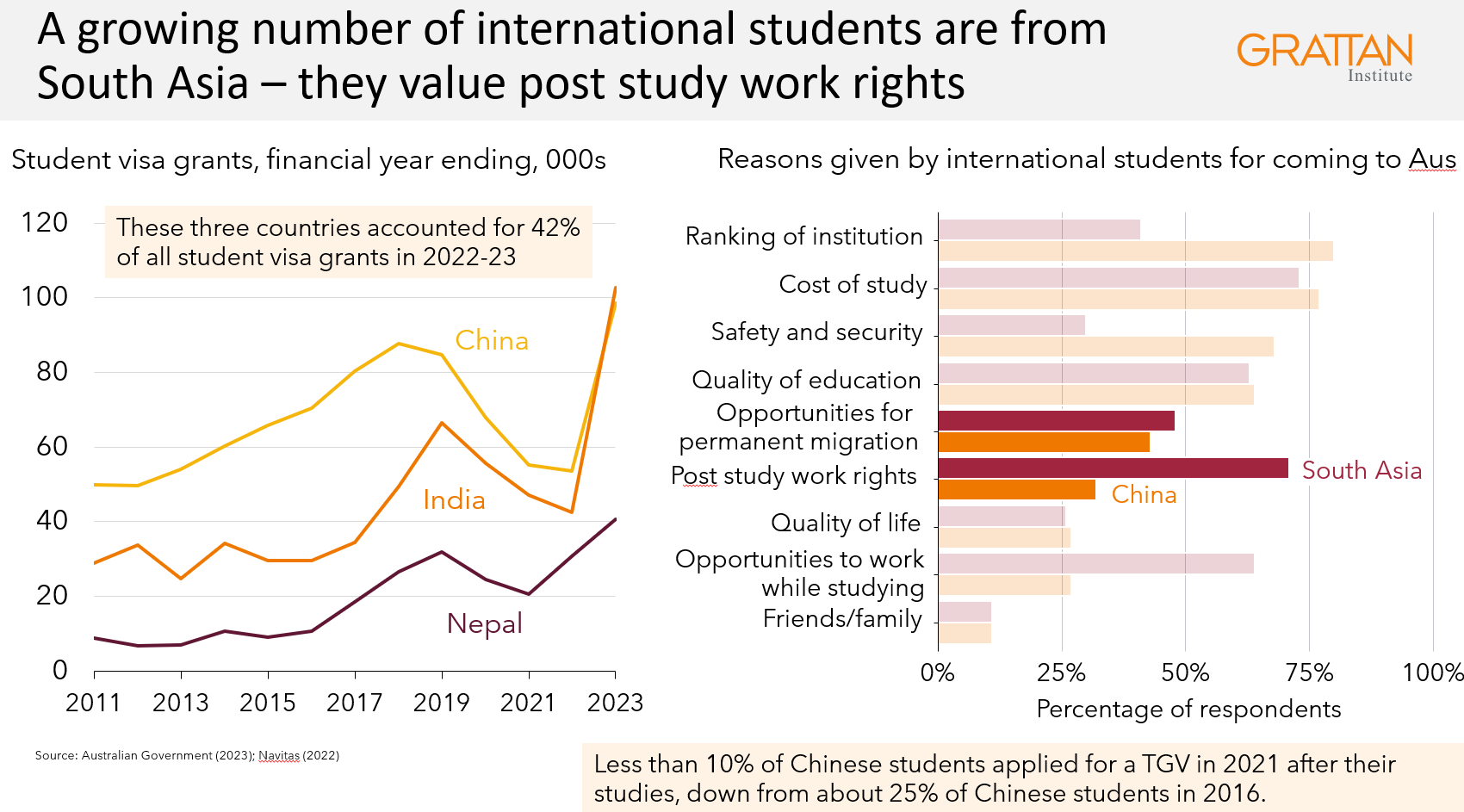

These generous post-study work rights are especially sought by “students” from South Asia, who prioritise post-study work rights and prospects for permanent residency over most other considerations.

Last week, higher education expert Andrew Norton released research showing that one in five graduate (485) visas on issue are for the spouses or children of primary visa holders.

At least one in three graduate visas from India, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka are for family members.

Ridiculously, Australian immigration rules permit international students and graduates to bring family members with them, with spouses permitted to legally work for up to 48 hours a fortnight.

Norton warned that it was “very likely” that some groups (e.g., South Asians) were exploiting the graduate visa program by bringing their family members to access the job market en route to permanent residency.

Norton also predicted that the number of family members from the above South Asian nations will surge following the post-pandemic lift in students from those nations.

“The really big increase in new overseas student enrolments were in 2023 and 2024 and that will flow through to a big increase in people applying for 485 visas”, Norton said.

“So if they started a two-year-master’s degree at the beginning of 2023, they will have graduated by the end of 2024. We will start to see pretty significant numbers will start to apply now and in the coming months”.

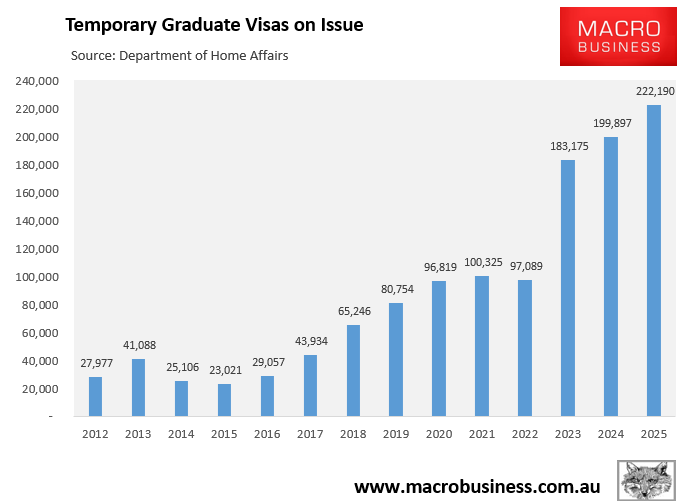

This week, the Department of Home Affairs released data showing that there were a record 222,190 graduate visas on issue at 31 March 2025. The figure represents an increase of 22,293 from last year’s high and a 125,371 increase from the pre-COVID level in Q1 2020.

This surge in graduate visas has been driven by students from South Asian nations, namely:

- Indian graduate visa numbers surged from 31,102 in Q1 2020 to 74,146 in Q1 2025, an increase of 138%.

- Nepalese graduate visa numbers surged from 13,848 in Q1 2020 to 33,312 in Q1 2025, an increase of 140%.

- Pakistan graduate visa numbers surged from 4,076 in Q1 2020 to 7,886 in Q1 2025, an increase of 93%.

- Sri Lanka graduate visa numbers surged from 3,230 in Q1 2020 to 8,804 in Q1 2025, an increase of 172%.

- Bhutan graduate visa numbers surged from 1,011 in Q1 2020 to 5,328 in Q1 2025, an increase of 427%.

For China, Australia’s largest international student market, graduate visas grew from 14,367 in Q4 2019 to 28,034 in Q4 2024, an increase of 95%.

The fact that Australia permits international students and graduates to bring their spouses and children with them, effectively converting them into de facto work and residence visas, is truly astonishing.

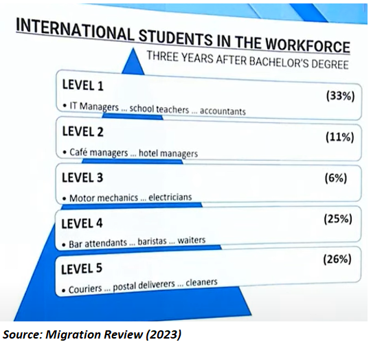

The Grattan Institute found that graduate visa holders are typically low-paid, earning significantly less than domestic graduates.

The 2023 Migration Review also revealed that more than half (51%) of international bachelor’s degree holders were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation.

The federal government should stem the growth in student and graduate visas by aiming for quality over quantity via the following types of policy reforms:

- Increase English-language proficiency criteria and require prospective students to pass entrance exams before applying for a study visa.

- Significantly increase financial requirements, including requiring students to deposit money in an escrow account before coming to Australia.

- Limit the number of hours that overseas students can work and cut off the direct relationship between studying, working, and acquiring permanent residency.

- Close down the numerous shady private colleges that operate as visa mills.

- Allow only distinction-level or higher international graduates to get post-study 485 visas.

- Allow only postgraduate overseas students to bring family members.

- Increase the temporary skilled migration income threshold to more than the median full-time earnings (now around $95,000).

These types of reforms would drastically lower the number of overseas students and graduates while increasing the average quality and productivity of the migration system.