The composition of Australia’s international student enrolments has changed drastically over the past 20 years.

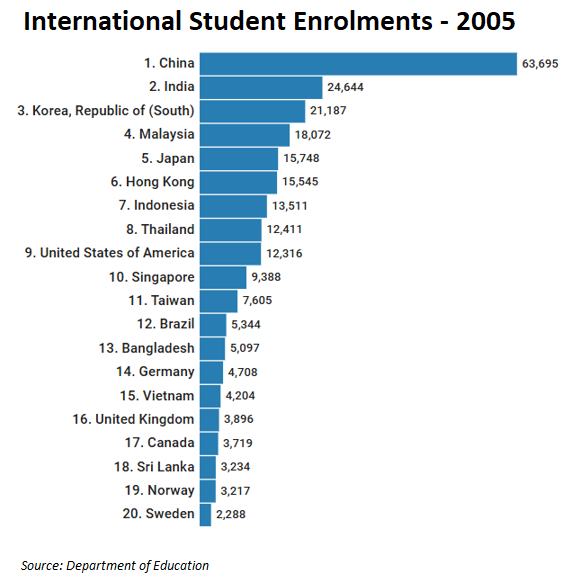

In December 2005, 288,579 overseas students were studying in Australia.

China (63,695) dominated enrolments, with India (24,644) in a distant second position. The Department of Education didn’t even list Nepal.

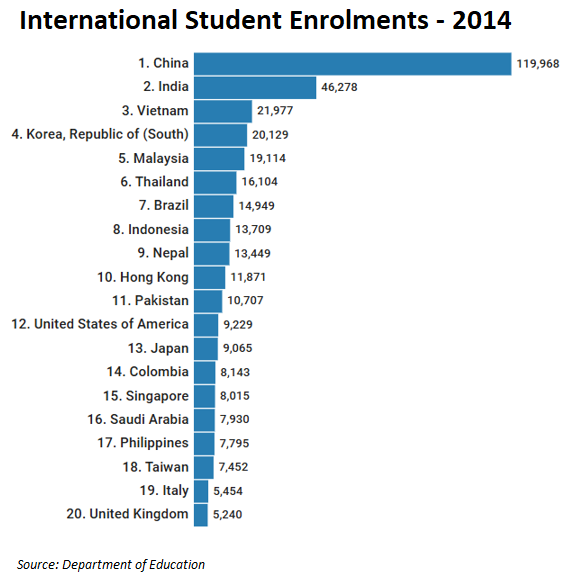

Nine years later, in December 2014, 452,965 overseas students enrolled in Australia.

China (119,968) continued to dominate, with India (46,278) a distant second. Nepal (13,449) was also climbing the ranks.

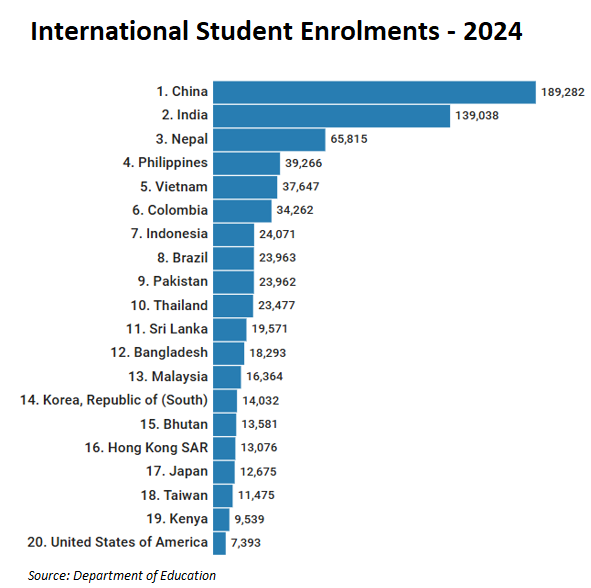

Fast forward another decade to December 2024, and 853,045 overseas students were studying in Australia.

Although China continued to have the most overseas students (189,282), the number of Indian (139,038) and Nepalese (65,815) students had increased dramatically:

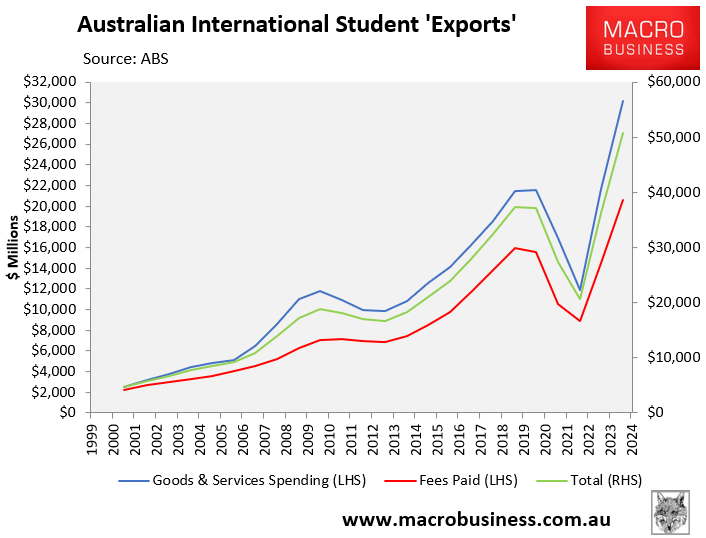

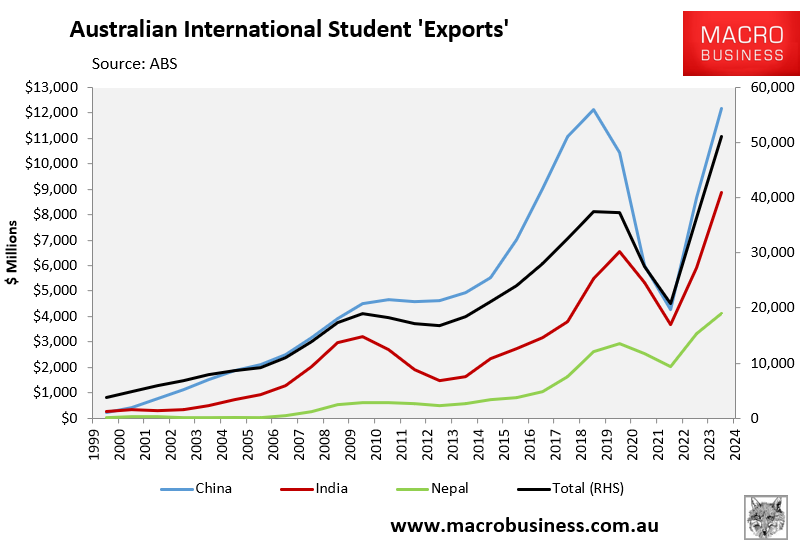

The same can be said for education exports, which are calculated as expenditure on goods and services in Australia, regardless of the source of income.

In 2023-24, education exports were valued at $51 billion, comprising $20.6 billion of tuition fees and $30.2 billion of spending on goods and services.

As illustrated below, China ($12.2 billion) accounts for the largest share of education exports, followed by India ($8.9 billion) and Nepal ($4.1 billion).

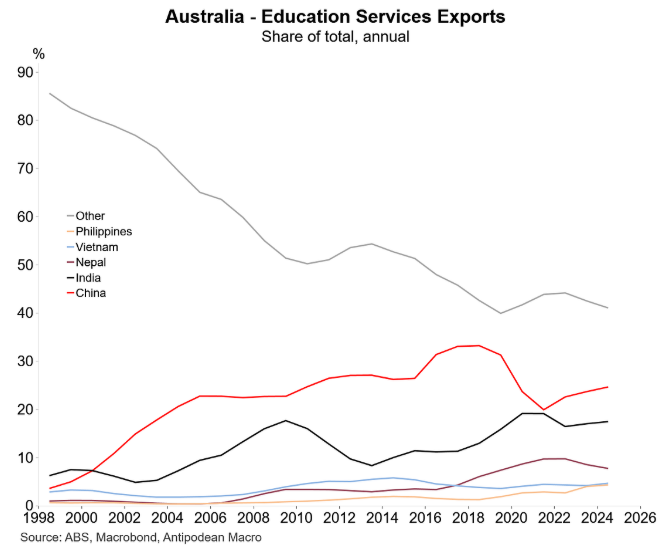

However, as Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro illustrates below, India and Nepal have increased their share of education exports, especially since 2018.

Consider the following data points:

- In 2005, China accounted for 22% of education exports. By 2024, that share had increased to 24%.

- In 2005, India accounted for 9% of education exports. By 2024, that share had risen to 17%.

- In 2005, Nepal accounted for less than 1% of education exports. By 2024, that share had increased to 8%.

This shift in composition toward South Asian students raises quality concerns in Australia’s international education sector.

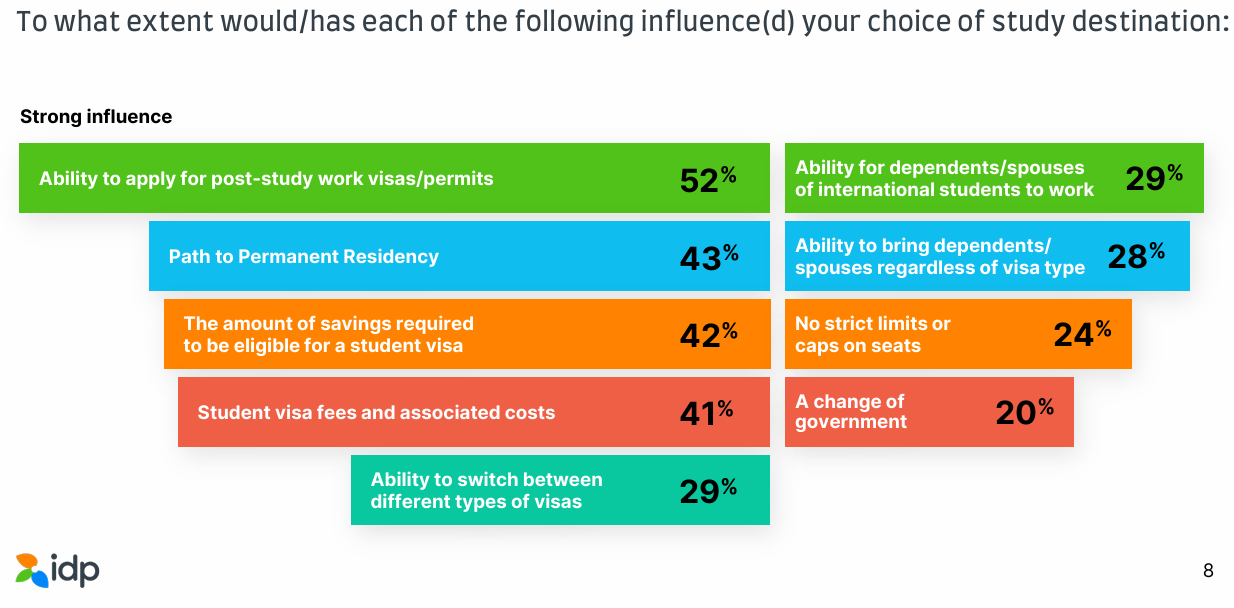

A 2022 Navitas poll of study intentions showed that students from South Asia and Africa chose a study destination based on their ability to obtain work rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency.

South Asian and African students prioritise employment and migration over education quality.

Students from these two continents are largely unconcerned about educational quality.

With the exception of students from China and Europe, all source countries place a high importance on the ability to work while studying and post-study job options.

The most recent IDP Emerging Futures survey also showed that post-study work opportunities (52%) are the most important consideration for international students when choosing a study destination. Pathways to permanent residency ranked second at 43%.

Indeed, Australia has seen the most significant increase in student numbers from countries that support themselves through paid employment, whereas only one-fifth of Chinese students do the same.

As a result, the concept of education ‘exports’ only fully applies to Chinese students, who mostly pay their tuition and living expenses using money from China rather than income earned in Australia.

As noted in Associate Professor Salvatore Babones’ recent book “Australia’s Universities, Can They Reform”:

“In reality, everyone (except perhaps the government and the universities) knew that many international students pay for their courses out of the proceeds of their work in-country, often working excessive hours under exploitative conditions, in violation of their visa terms”.

“This situation is especially common among South Asian students, and is reflected in the steep fall-off in South Asian student numbers when teaching moved online”.

“With prospective students unable to rely on employment income in Australia to support their studies, new commencements of Indian students at Australian higher education providers fell 65% between 2019 and 2021; for Nepali students, the decline was 37%; for Pakistanis, 45%; for Sri Lankans, 54%”.

“These countries are simply too poor to send large cohorts of international students to Australian universities based on family resources alone”.

“For many South Asian students, a student visa is a very expensive but thinly disguised work visa”.

The preceding analysis demonstrates why international education is primarily a people-importing immigration industry rather than a legitimate export industry.

Student visas are often thinly veiled low-skilled work visas.

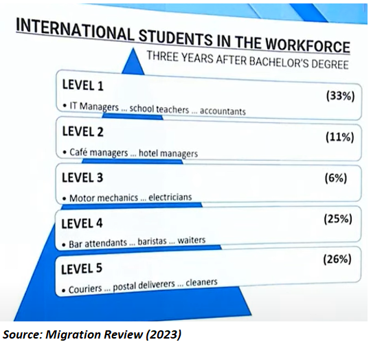

The same holds true for international graduates who have completed their studies. According to the 2023 Migration Review, 51% of international graduates with bachelor’s degrees who had been in Australia for three years worked in low-skilled employment.

The exception is Chinese students, who mostly enroll in Group of Eight universities, pay their expenses using money from China rather than income earned in Australia, and leave Australia after their studies.

The truth is that significant restrictions on work rights and permanent residency would lead to a collapse in students arriving from non-Chinese source nations.

Student visas are backdoor work and residency visas for students from these nations.