Developers have ridiculed the Minns government’s plan to fix the state’s housing crisis with a Parisian-style medium-density housing blitz.

The transport-oriented development (TOD) scheme, launched by the Minns government, allows low-to mid-rise developments within 400 metres of 37 train or metro stations across Sydney.

However, industry leaders claim that homeowners band together to drive up land prices, while developers struggle to amalgamate plots.

Land values across NSW surged to almost $3 trillion last year, driven by an insatiable demand for land across Greater Sydney.

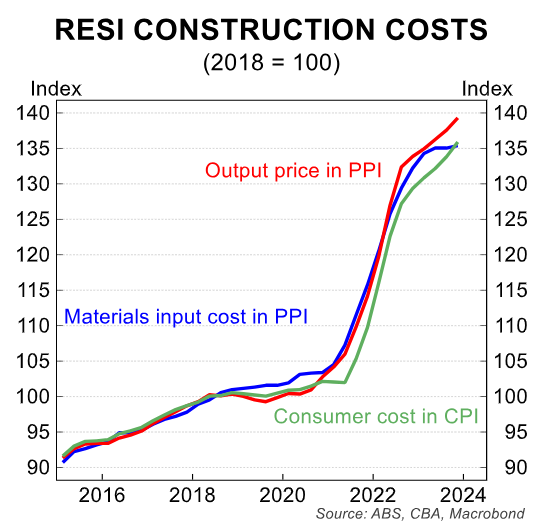

Master Builders Australia estimates construction costs have increased by 40% over the past five years, while build times have blown out by over 40%.

Strathfield-based developer Mark Harb claims that if his company were to build a medium-density residential development in the Homebush TOD, he would make a $6 million loss.

Harb said the costs of purchasing the land and building the housing would be more than $50 million, but he would only get $44 million back from the sale.

Peter Yannopoulos from Manticore Projects said high costs pushed developers to hold their developments instead of selling.

“Right now we’re building higher end townhouses in Berry, if I add land costs and construction costs, I’m probably looking at spending $800,000 on average for each one, I’ll be lucky if my resale is $850,000 (for each one)”, he said.

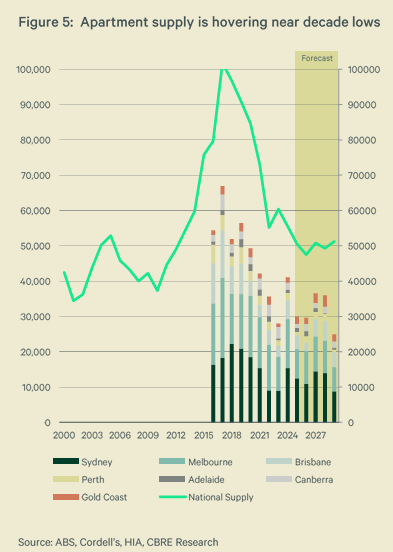

The concerns raised above echo those of CBRE late last year, which predicted that Australia would only build 50,000 units per year between 2025 and 2029.

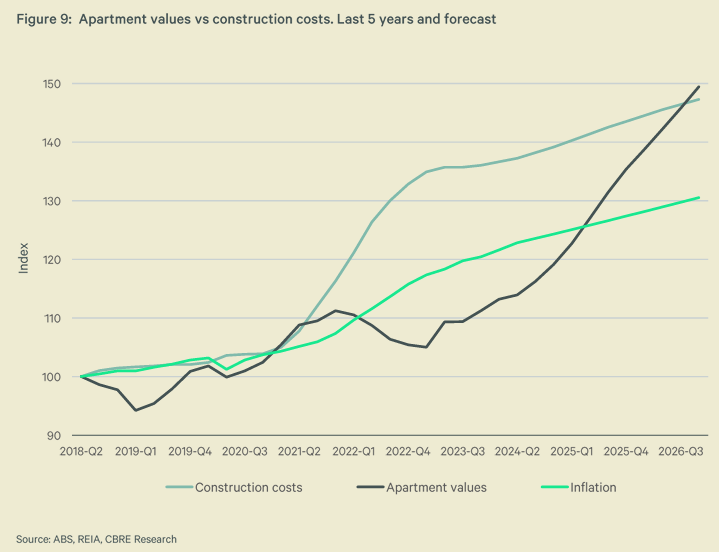

CBRE argued that apartment prices needed to catch up with rising construction costs in order to make it feasible for developers.

Separately, Charter Keck Cramer stated that apartment prices for new and established stock needed to rise by around 15% to entice development. However, this would price many would-be buyers out.

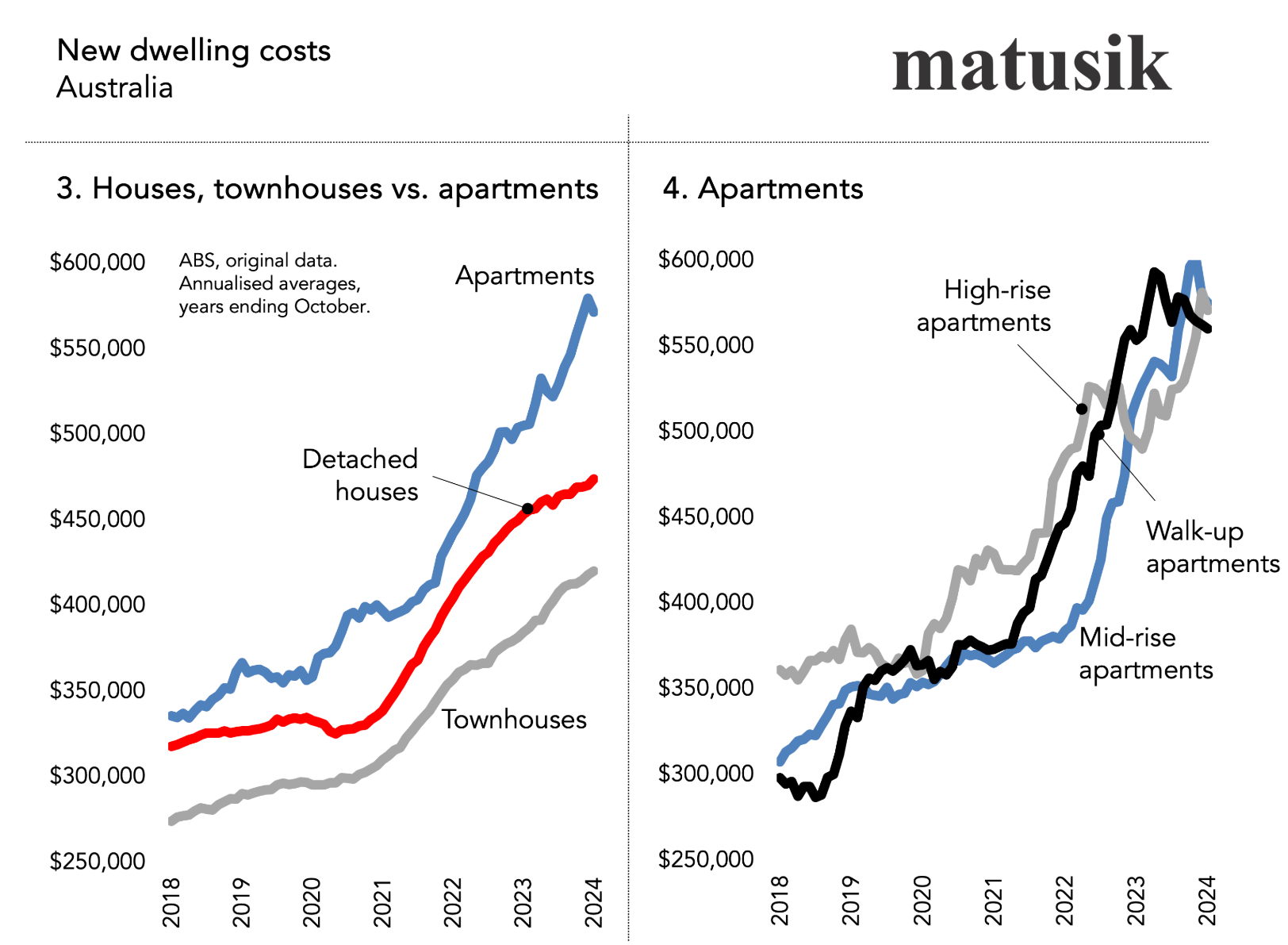

The following chart from Michael Matusik highlights the central problem. Build costs are too high, as are land costs. Both are key roadblocks to building more homes.

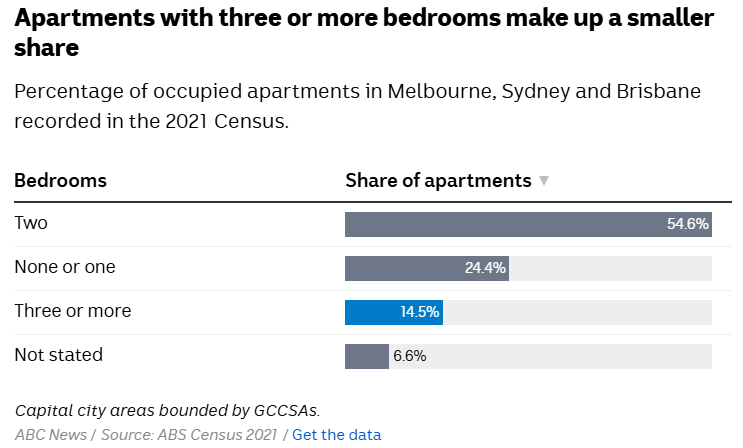

Meanwhile, developers have compensated for rising costs by shrinking apartment sizes.

Three-bedroom apartments comprise only a tiny fraction of the nation’s apartment stock.

“Three-bedroom and four-bedroom apartments have more square metres”, Stuart Ayres from the Urban Development Institute of Australia’s (UDIA) New South Wales chapter noted last month.

“You just multiply that additional number of square metres by the cost per square metre and you have a more expensive dwelling”.

UDIA warned that the current economic conditions have made it harder to deliver family-friendly apartments, noting that three- and four-bedroom apartments are “quite uncompetitive compared to existing detached housing stock”.

“The feasibility for many multi-storey apartment buildings is just not there under the current conditions”, Ayres said.

The notion that by building many apartments, affordability and livability would improve is delusional.

There are also legitimate concerns surrounding the construction quality of new apartments and excessive strata fees.

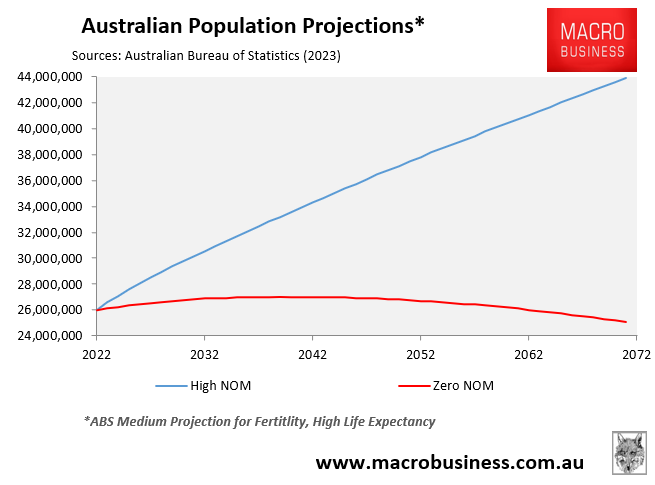

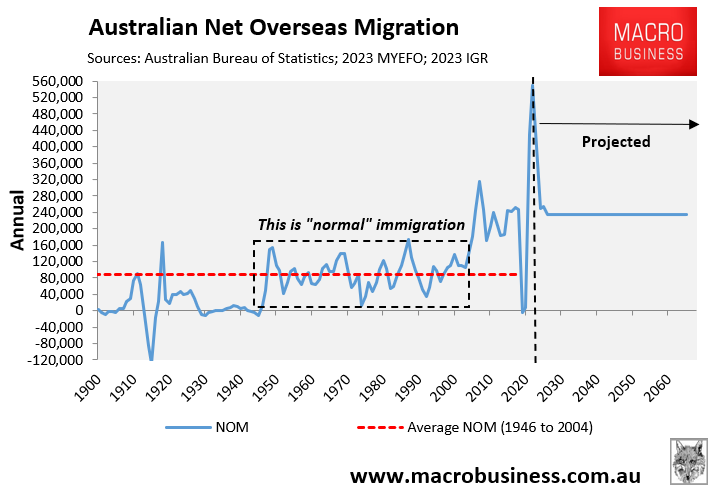

The reality is that Australia’s big cities would not have to become high-rise slums if the federal government slowed population growth through moderate net overseas migration.

The cheapest, simplest, and quickest solution to Australia’s housing supply problem is to limit net overseas migration to a level well below the capacity to supply housing and infrastructure.

Australia’s housing crisis is the direct result of excessive population demand, not a lack of supply.

Future Australians should not be forced to live in expensive shoeboxes in the sky.