The Australian’s Matt Bell published an article on the nation’s “skills crisis”.

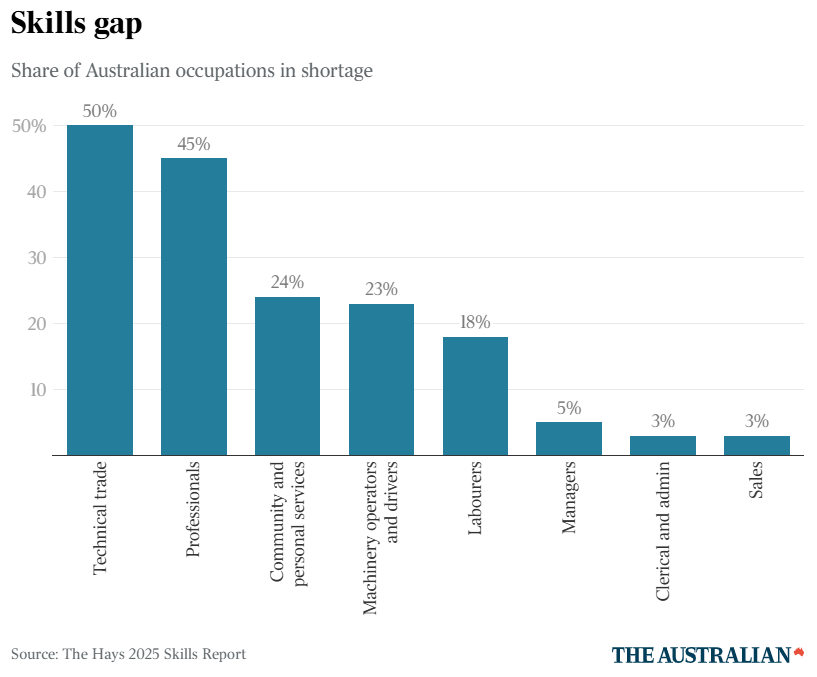

It is based on a report from recruitment firm Hays, which found 85% of hiring managers are grappling with “skills gaps” that continue to worsen despite a softer market and strong immigration.

While skilled migration is frequently cited as a solution, only 37% of companies said they use it to address shortages, and roughly a quarter believe it skilled migration has failed to meet expectations.

“At a country level when you think about skilled migration you are buying skills and importing it from another country”, Hays Asia-Pacific chief executive Matthew Dickason said.

“Those migrants come with skills but don’t necessarily understand the Australia and New Zealand landscape that well, so if we can get them proficient in what we do and more accepting of them then that will help us a society realise the benefits from skilled migrant”.

When will policymakers admit that Australia’s mass immigration policy has failed?

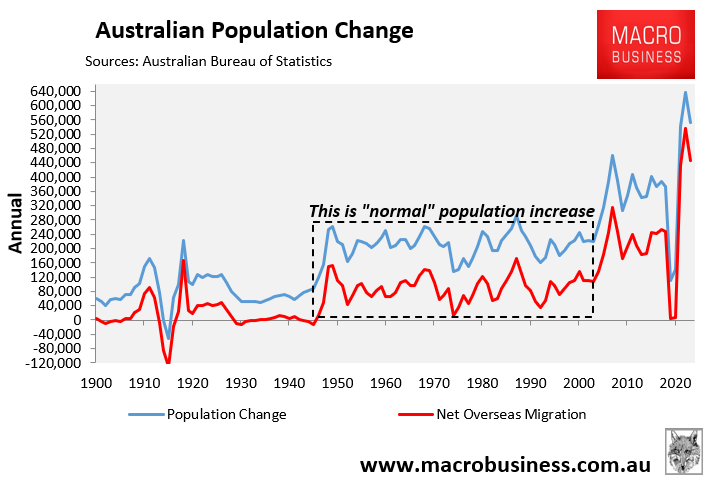

Australia’s population has ballooned by 8.5 million people this century, representing a 45% increase due to record levels of immigration.

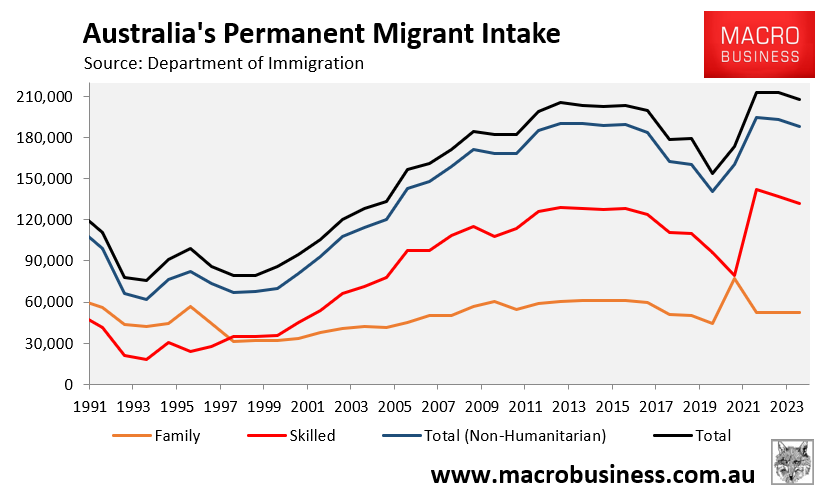

Most of Australia’s immigration is also purportedly ‘skilled’.

Yet, despite decades of high net overseas migration, skills shortages are worse than ever, alongside chronic shortages of housing and infrastructure.

The reality is that Australia’s immigration system is not skilled, which has created severe mismatches across the economy.

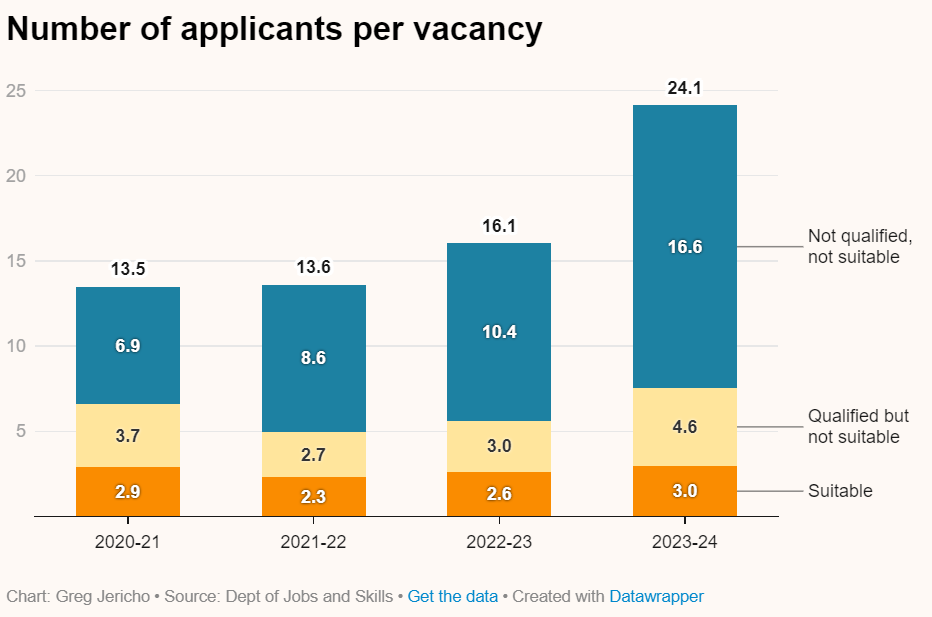

As shown recently by Greg Jericho, these shortages were not because of a lack of applicants. “There are a lot more people applying for each job”.

Rather, it was because of a lack of “qualified and suitable candidates applying for jobs”.

Most of Australia’s ‘skilled migrants’ work in lower-skilled areas unrelated to their qualifications.

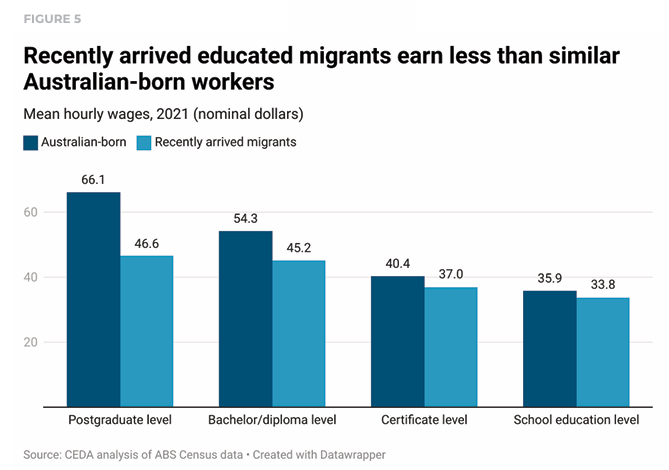

The Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) analysed the latest census, which showed that Australia’s ‘skilled’ migrants are chronically underemployed and underpaid.

“Recent migrants earn significantly less than Australian-born workers, and this has worsened over time”, CEDA senior economist Andrew Barker said.

“Many still work in jobs beneath their skill level, despite often having been selected precisely for the experience and knowledge they bring”.

The CEDA report also warned that Australia’s migration system could be contributing to Australia’s poor productivity growth.

“Labour productivity and wages are closely linked, indicating that migrant labour is not being used as productively as it could be”, the report said.

“This decade, migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”.

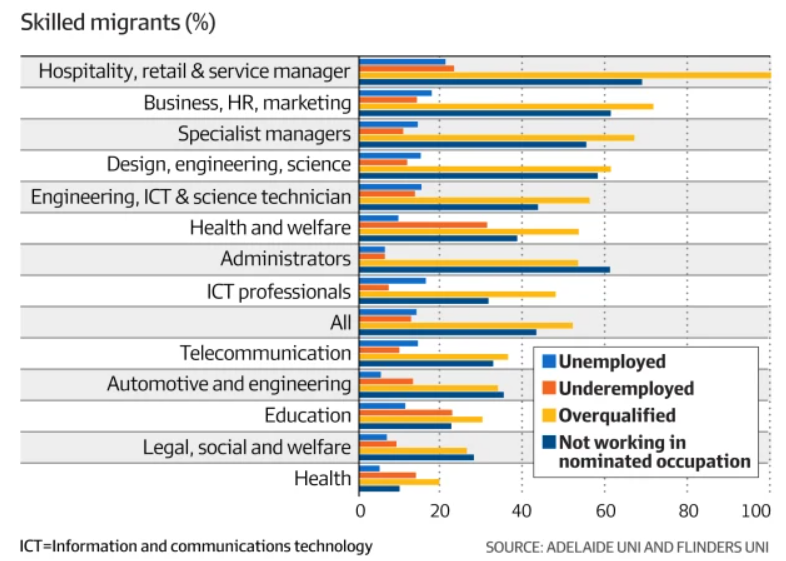

Research from Adelaide University’s George Tan showed that 43% of skilled migrants who used the state-government-sponsored visa system were not engaged in their nominated occupation.

Most skilled migrants worked in retail, hospitality, and service management and were overqualified.

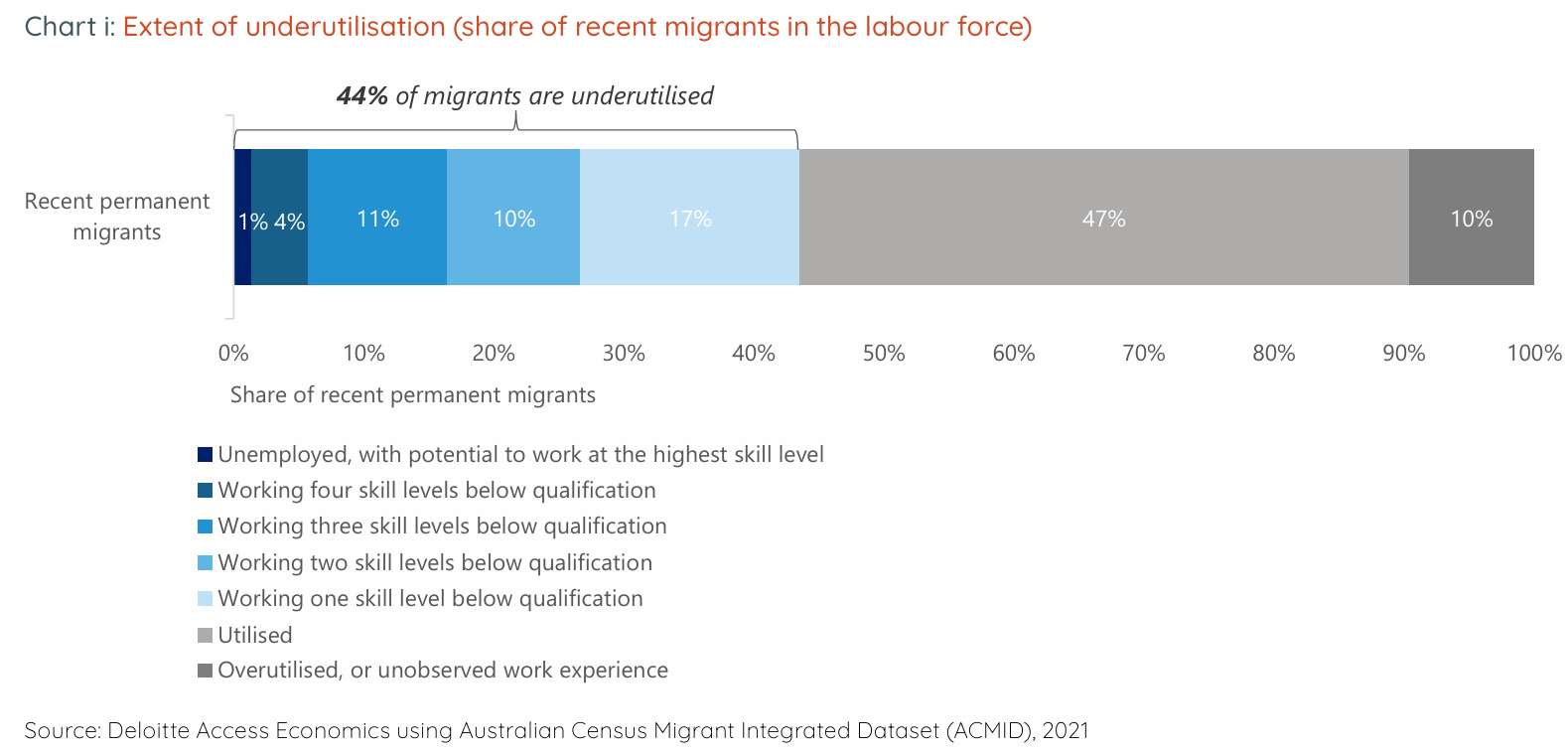

Research undertaken by Deloitte Access Economics found that 44% of permanent migrants in Australia were working in jobs below their skill level in 2023. Most of these underemployed migrants also entered via the skilled stream.

Deloitte estimated that more than 620,000 permanent migrants work below their skill levels and qualifications. Of these, about 60%, or 372,000, arrived in the skilled migration system.

On average, among those permanent migrants who arrived in Australia in the last 15 years, almost half (44%) are working in an occupation at a lower-skill level than is commensurate with their qualifications (Chart 1).

This means in 2024, there are more than 621,000 permanent migrants living in Australia who are underutilised and not working to their full potential.

Despite the permanent migration program’s focus on attracting overseas qualified professionals with skills in demand that address labour shortages, almost six in ten underutilised permanent migrants in Australia entered via the skills stream.

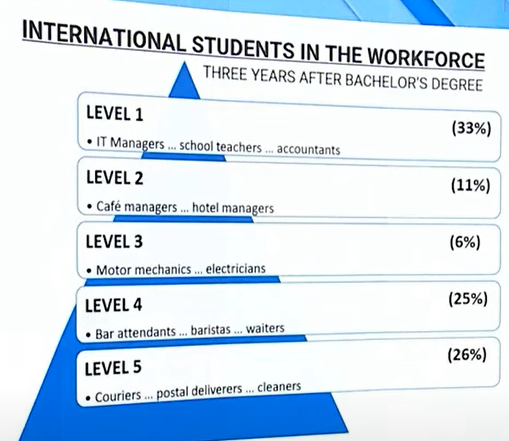

The federal government’s 2023 Migration Review revealed that 51% of overseas-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation:

Source: Migration Review (2023)

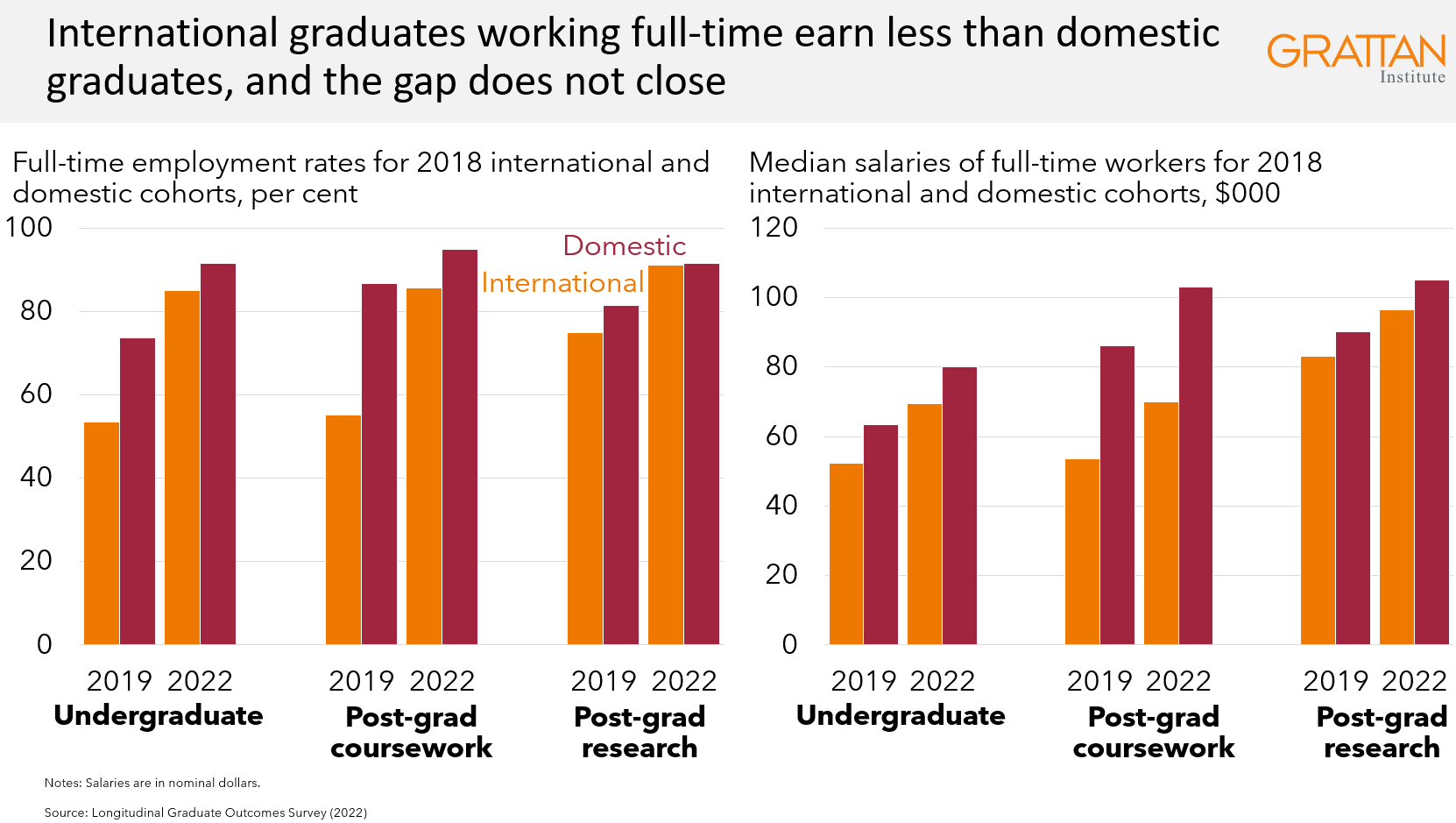

The Graduate Outcome Survey has also consistently shown that student graduates earn far less than local-born graduates and have worse labour market outcomes:

What further evidence is needed to prove that Australia’s immigration system is failing to deliver the outcomes that it has promised?

Mass immigration has failed to deliver the right skills and has created chronic infrastructure and housing shortages, alongside damaging the natural environment.

The optimal approach is to run a smaller, genuinely skilled, and higher-paid migration system.

The wage floor for all skilled visas should be set at a level far above the median full-time salary (currently around $90,000). All skilled visas should also be employer-sponsored so that skilled migrants begin working in their field of expertise immediately.

All forms of retirement visas—parental and ‘golden’ ticket’—should also be abolished.

The malfeasance of Australia’s immigration system cannot be ignored. Australia is robbing poor nations of talent while worsening skills, housing, and infrastructure shortages domestically.