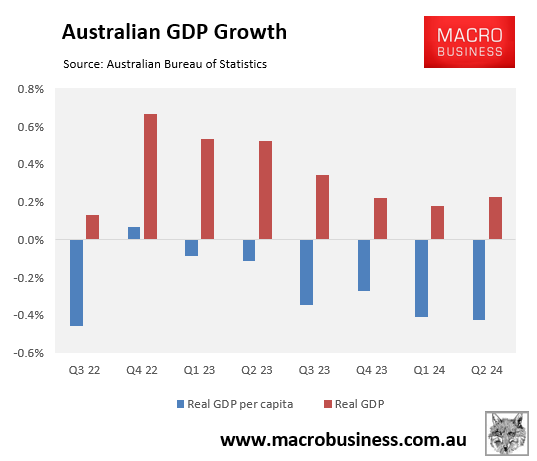

Australia’s economic growth is a mirage, powered by unprecedented immigration volumes and record public spending.

While the overall economy has expanded modestly, per capita GDP has declined for six consecutive quarters.

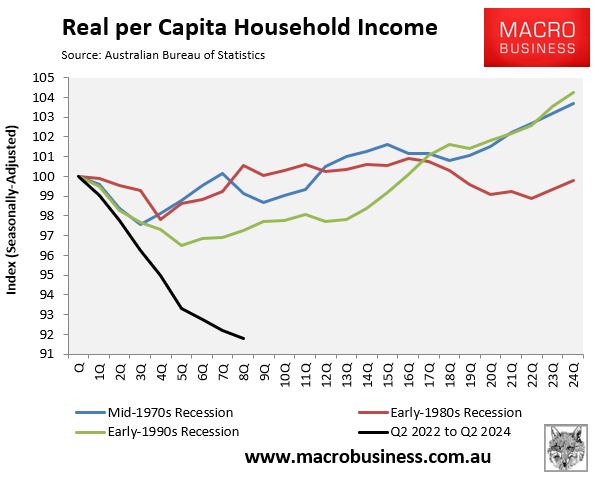

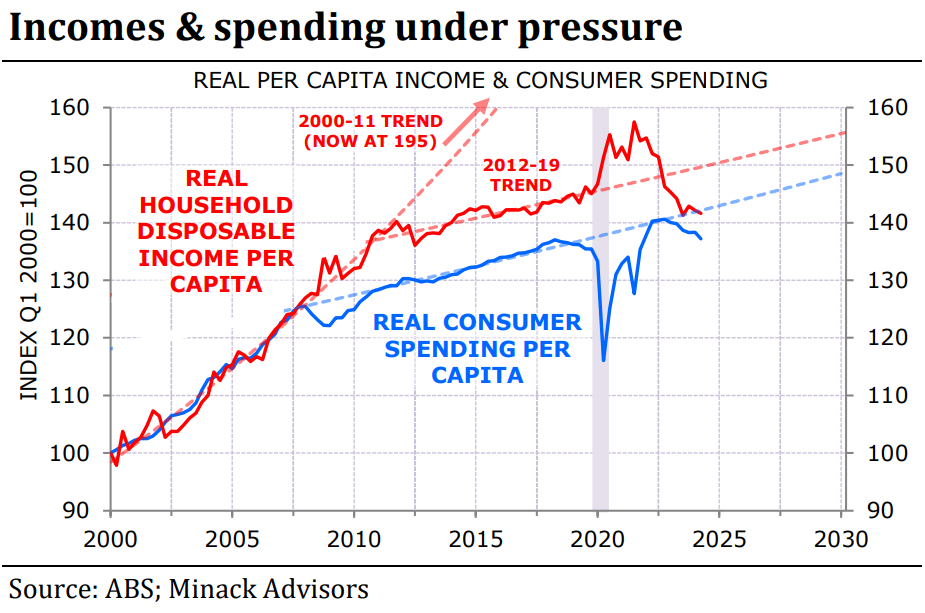

Worse, Australians have suffered the sharpest decline in real per capita household disposable incomes on record, as illustrated below.

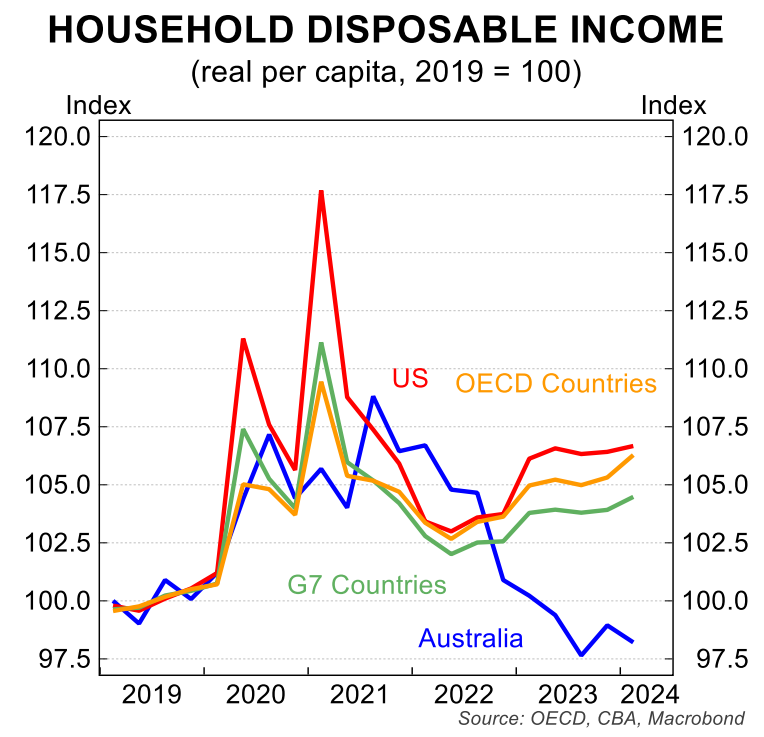

Australia’s real per capita household income decline has also been at odds with that of other developed nations.

Over the weekend, The Australian claimed that Australians were “suffering the worst decline in living standards since the 1950s with the fall in real disposable income eclipsing those of the last four major recessions including the 1970s inflation crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic”.

Independent economist Chris Richardson said the drop in living standards was unprecedented since the index was first measured, and he warned of the political ramifications.

“What you’re seeing with approval ratings and election outcomes with leaders around the world is that those holding the baby at the moment when inflation rips through living standards have paid the price”, Richardson said.

“The challenge for Australia is that the impact on our living standards has been far greater than anywhere else. There is no argument that the fall (since 2022) is bigger than anything we have seen since 1959”.

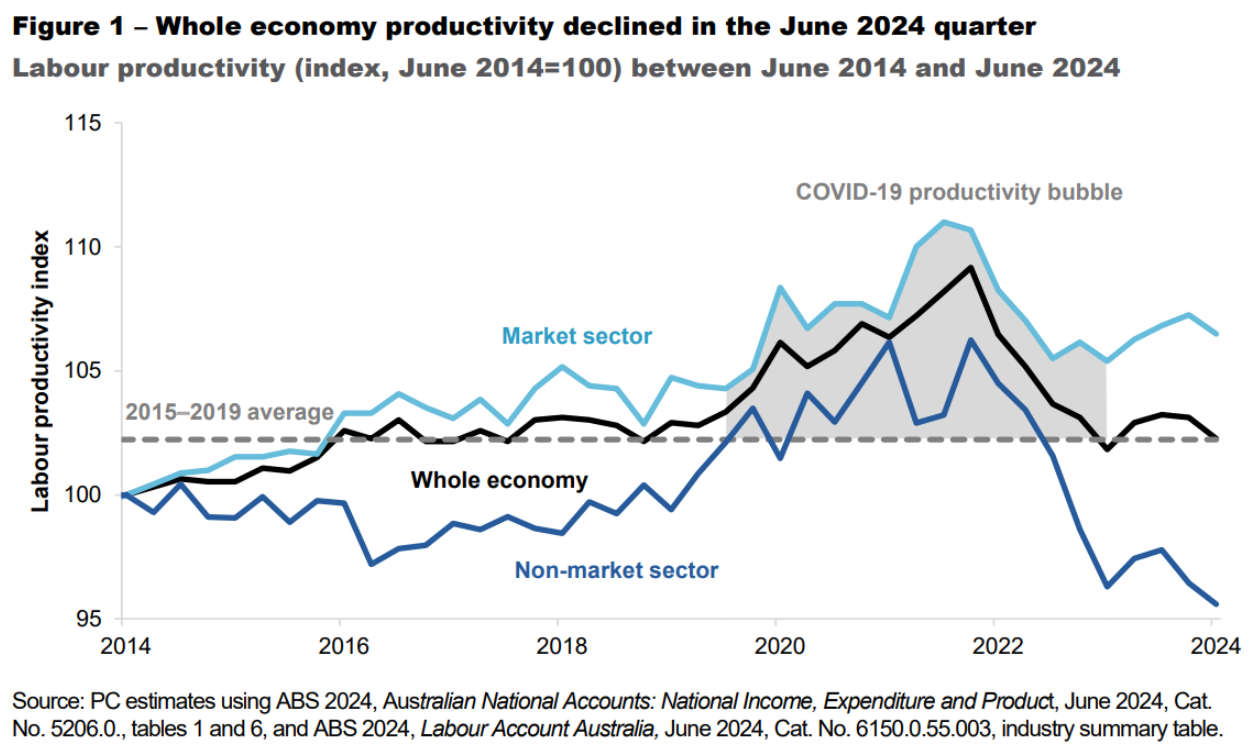

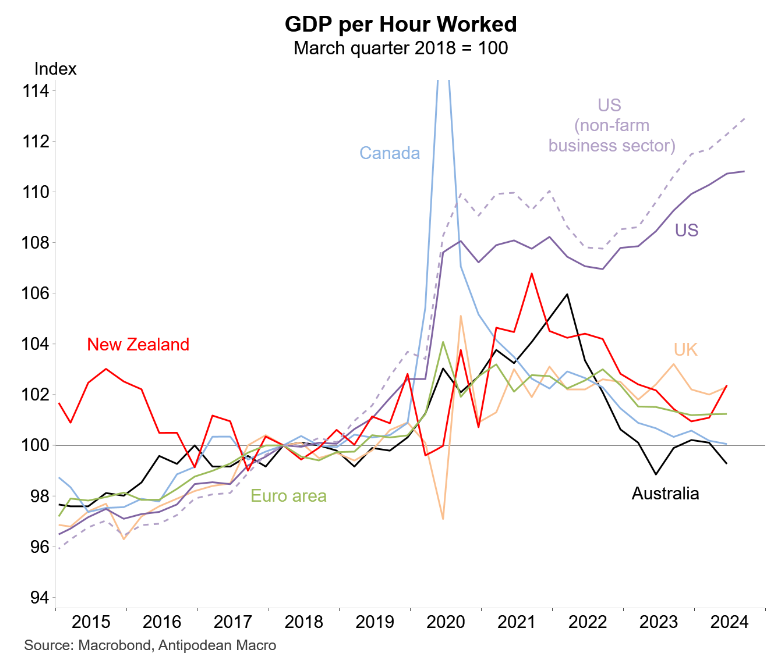

Richardson added that Australia’s productivity is “as sick as a dog”, paralleling the 1970s stagflationary period. As a result, Australia is experiencing a “lost decade”.

“Today, our productivity is worse. It is a similar slowdown story, but it has slowed down from a weaker starting point”, Richardson said.

“The living standards story shows we have had a lost decade, we have spun our wheels as a nation, and you could almost time it to the Hockey budget of 2014 when all our politicians retreated and decided not to be courageous”.

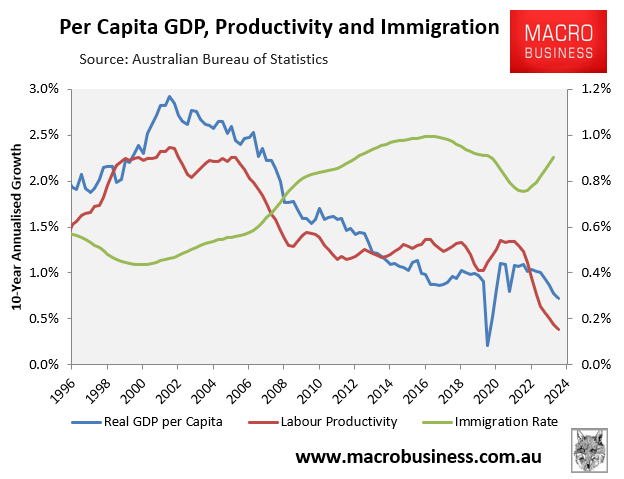

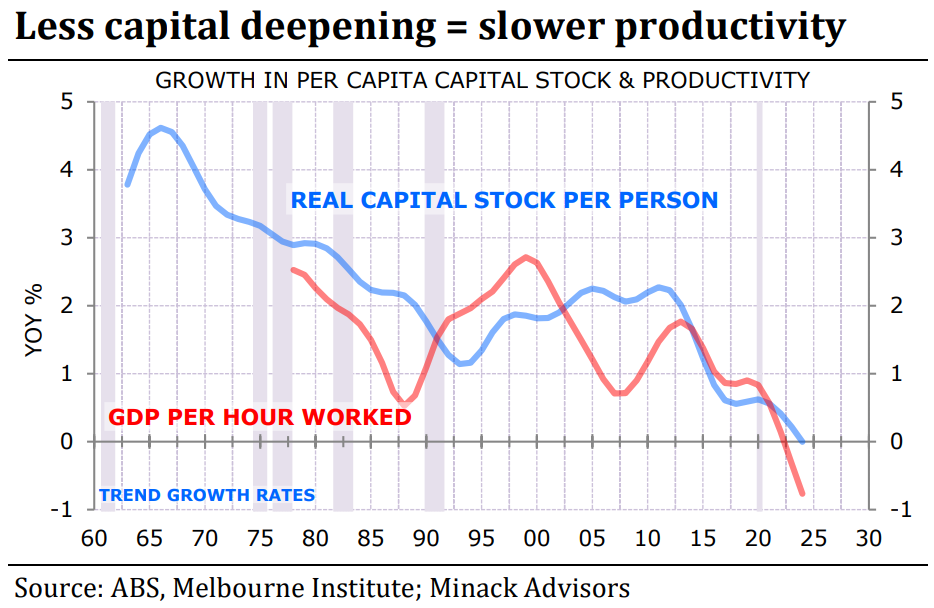

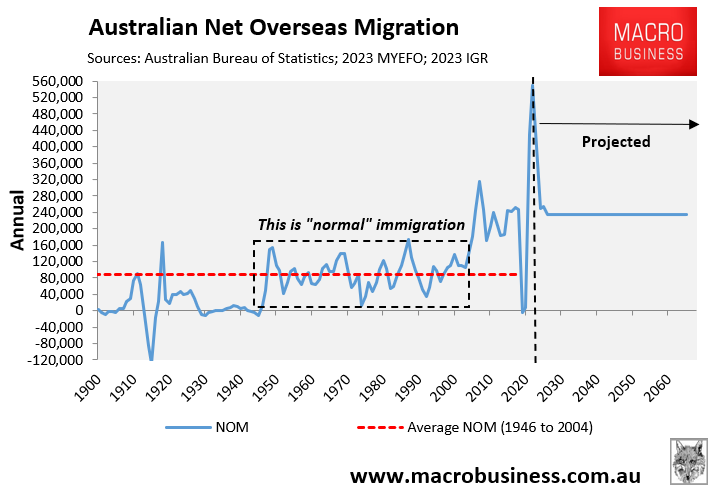

Australia’s long-term productivity decline correlates with the increase in immigration in the mid-2000s.

The federal government more than doubled Australia’s net overseas migration, reducing productivity through what economists call “capital shallowing”.

When a country’s population expansion outpaces its business, infrastructure, and housing investment, it produces less capital per worker, resulting in lower productivity and slower per capita growth.

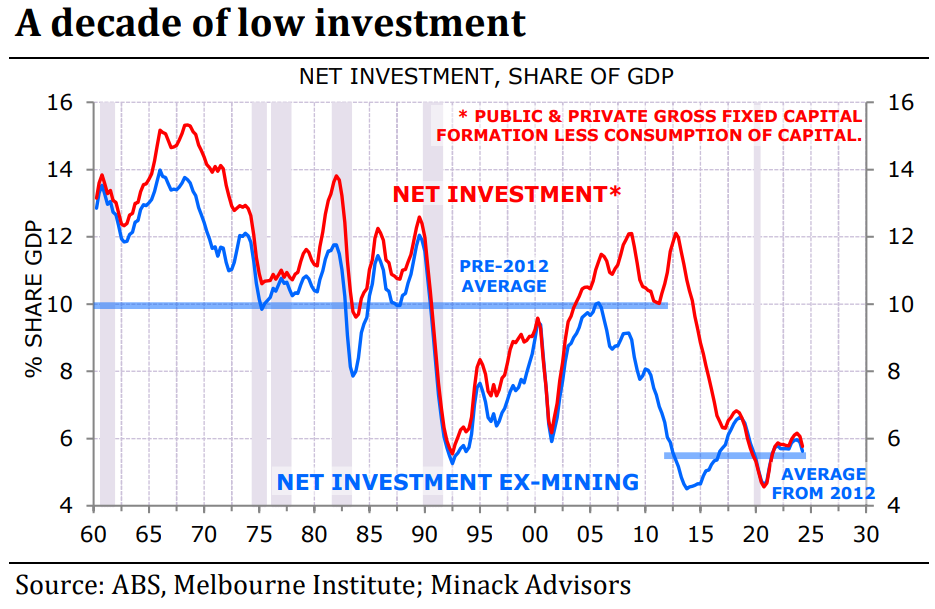

Independent economist Gerard Minack showed last month that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

Worse, that “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

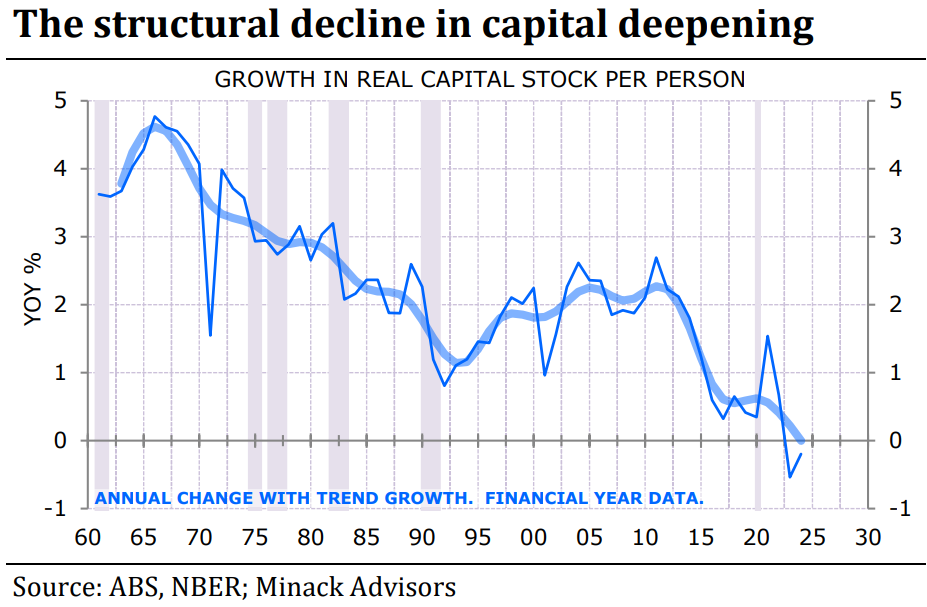

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

As a result, Australia is caught in a productivity trap because the federal government has committed to running a permanently high immigration program, which will lead to further capital shallowing (or at least less capital deepening).

Unless productivity growth magically picks up, Australia faces decades of below-par economic and income growth.

The productivity morass has also been exacerbated by massive government spending in areas like the NDIS, which has expanded employment in low-productivity non-market jobs.