Australia’s federal and state governments hope to achieve National Cabinet’s 1.2 million housing target by bulldozing middle-ring suburbs into high-rise apartments.

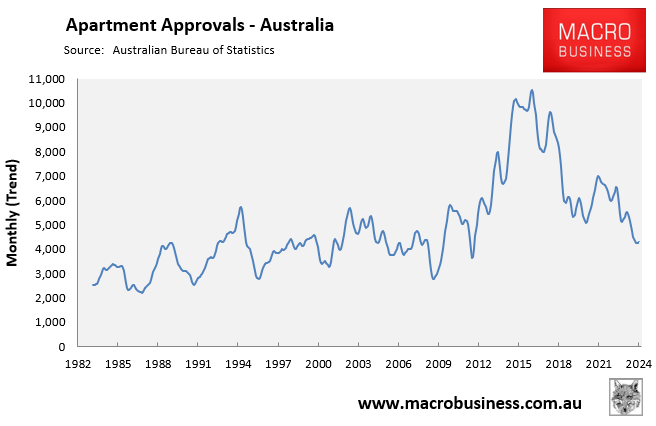

Tuesday’s dwelling approval data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) drove a dagger through these hopes, with only 4300 units & apartments approved for construction in June in trend terms, to be around 60% lower than the peak of 10,500 in June 2016:

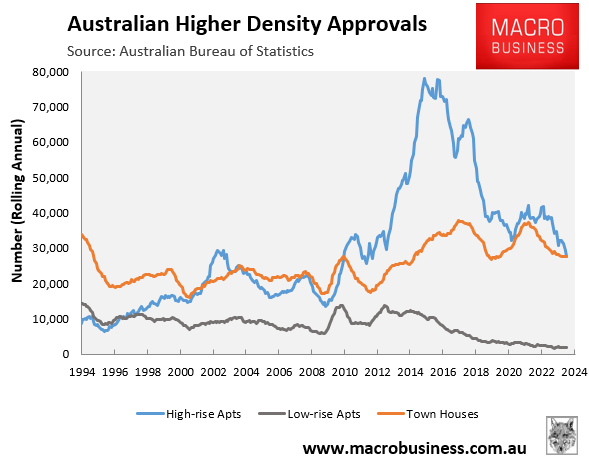

The next chart plots annual higher density approvals at the national level:

High-rise apartment approvals (i.e., four storeys or above) have collapsed by 65% from their 2015 peak, whereas low-rise apartments are down 87% from their 2013 peak and town houses are down 33% from the 2017 peak.

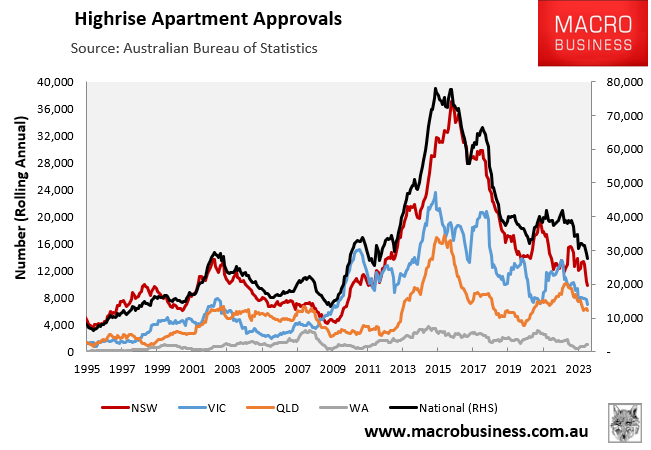

The following chart shows the annual decline in high-rise approvals at the national level and across the major jurisdictions:

The decline in approvals has been especially severe in NSW, down 74% from the September 2016 peak. Victoria (-70%) and Queensland (-64%) have also experienced sharp declines in high-rise approvals.

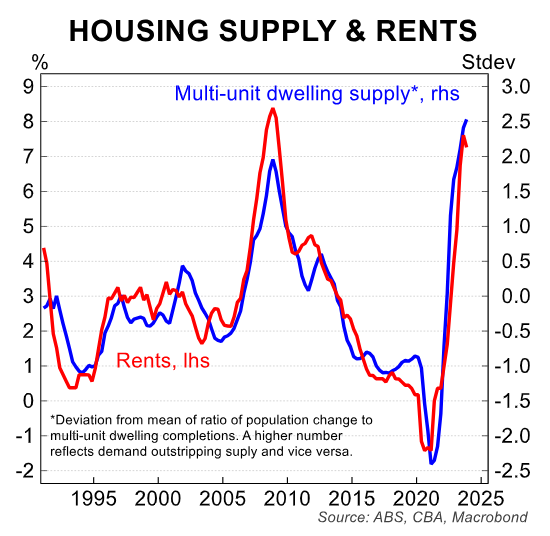

Earlier this year, CBA published the following chart showing how rental growth has been highly correlated with the ratio of population growth to new apartment construction:

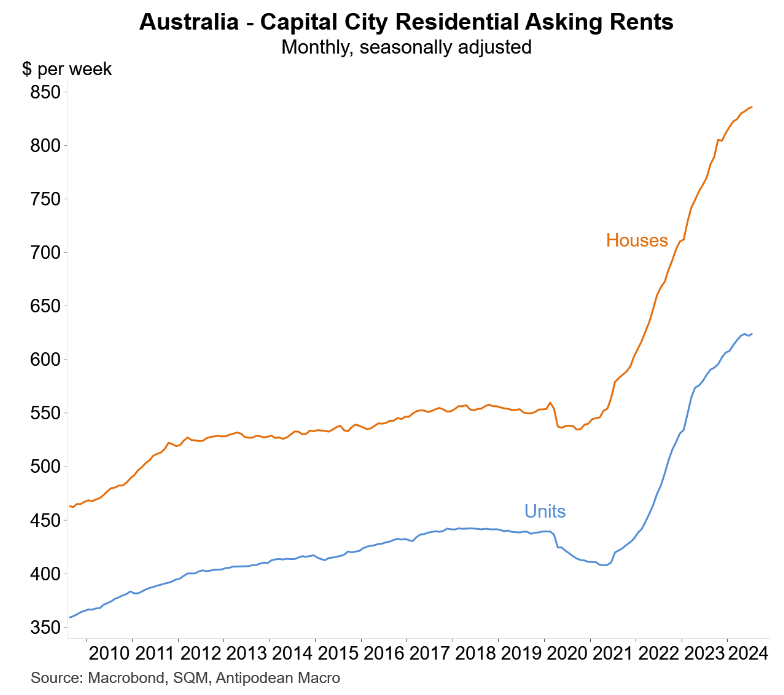

Unless there is a sharp pullback in immigration, the above dwelling approval data suggests that rental inflation will remain strong.

My prediction is that we will see a pullback in both immigration and apartment construction.

Indeed, the slowing of net overseas migration from its peak in Q3 2023 has had the most significant impact on the unit markets of the three major capitals, which have seen the greatest moderation in rental increases.

Given the stiff macroeconomic headwinds facing the homebuilding industry, namely:

- The highest official cash rate since 2011.

- The 40% surge in construction costs since the beginning of the pandemic.

- The residential building industry is competing for scarce labour and materials with government ‘big build’ infrastructure projects.

- The collapse of nearly 3000 construction firms in 2023-24.

The only realistic solution to the housing shortage and rental crisis is to dramatically moderate net overseas migration.