CoreLogic’s July housing report contained welcome relief for tenants.

Asking rents rose by only 0.1% over the month, the smallest monthly increase since July 2020.

The monthly change in rents was negative in Sydney and Brisbane (-0.1% in both cities and the first monthly decline since 2020) as well as Hobart (-0.3%).

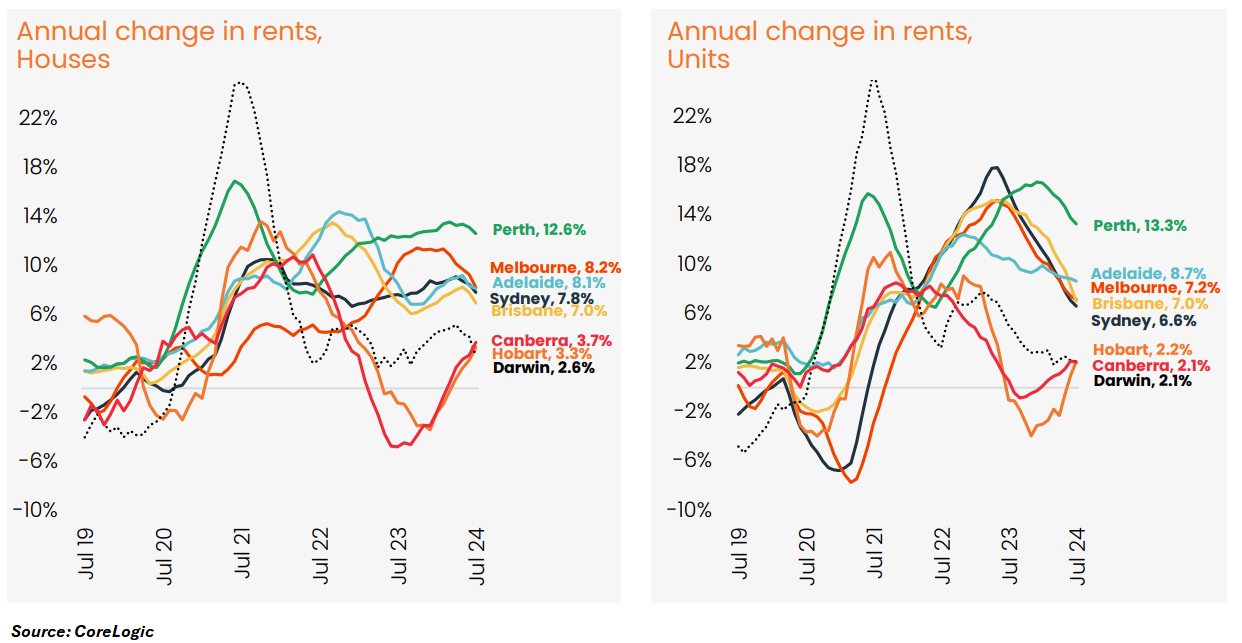

CoreLogic noted that the slowing in rental growth has been driven by the unit sector.

“The easing in rental growth aligns with the peak in net overseas migration in the first quarter of 2023″, Tim Lawless said.

“The large majority of overseas migrants, mostly students, arrive in Australia on temporary visas. Housing demand from overseas migration tends to favour inner city unit rental markets”.

The decline has been sharpest in Sydney where the annual growth in unit rents has eased from 17.9% in May last year to 6.6%.

Annual Melbourne and Brisbane unit rental growth has also eased more than 8 percentage points.

Nevertheless, unit rents continue to grow at a historically high pace.

Sydney unit rents still rose by 6.6% over the past 12 months, which is more than double the pre-COVID decade average (2.7% annual growth).

Growth in house rents is also easing in most cities, but remains at historically high levels.

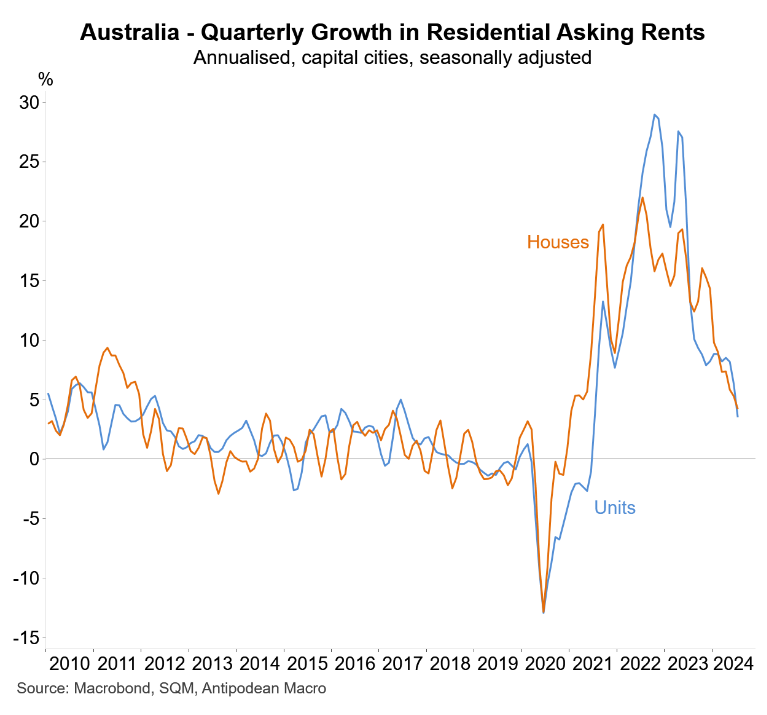

Separate asking rents data from SQM Research likewise showed a sharp moderation of rental growth, albeit off a very high base:

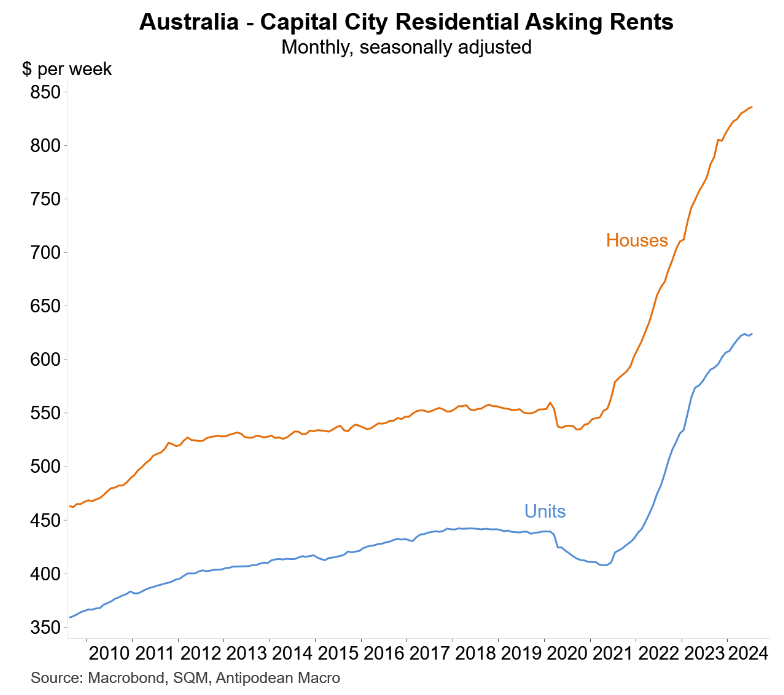

As you can see, capital city asking rents have experienced very strong growth since borders reopened, as illustrated below:

Rents appear to be approaching an affordability ceiling after increasing by around 40%.

Unlike mortgages, rents cannot be leveraged. This means that rental growth is more closely tied to household income, which limits its potential increase.

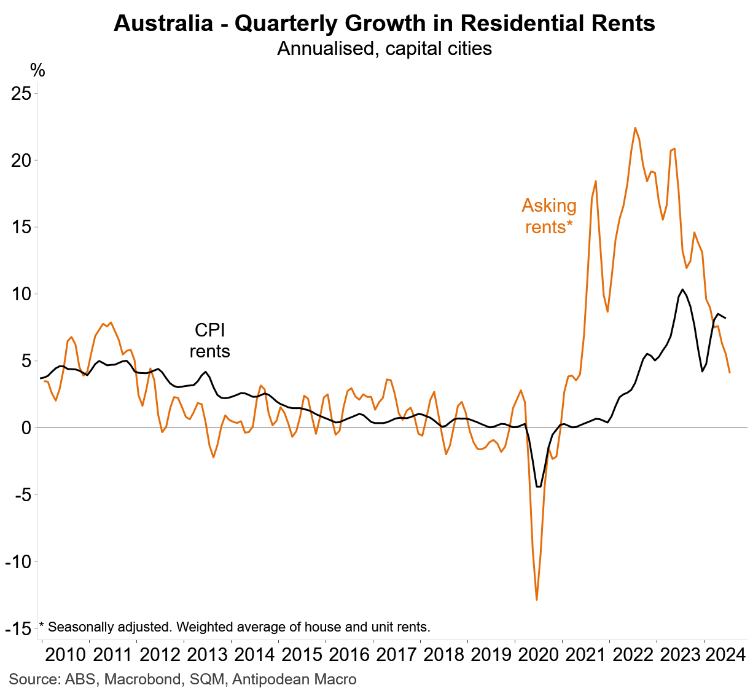

Finally, the next chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro shows that while rental growth is indeed fading, it “will take time to pass through to meaningfully lower CPI rents inflation”:

Therefore, rents will remain a ‘thorn in the side’ of the RBA in the period ahead.