Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Assistant Governor Sarah Hunter gave an address on Thursday in Hobart, in which she noted that the housing construction industry faces a “perfect storm”.

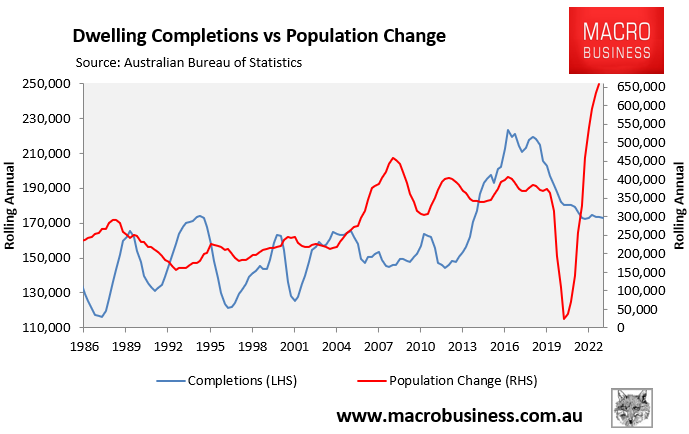

Hunter also warned that Australians face a prolonged period of rising home prices and rents as population growth via net overseas migration exceeds dwelling construction.

“The pace of population growth in Australia is typically faster than other advanced economies”, Hunter said.

“A growing population clearly implies that underlying demand for housing is rising over time – all of these extra people need a place to live”.

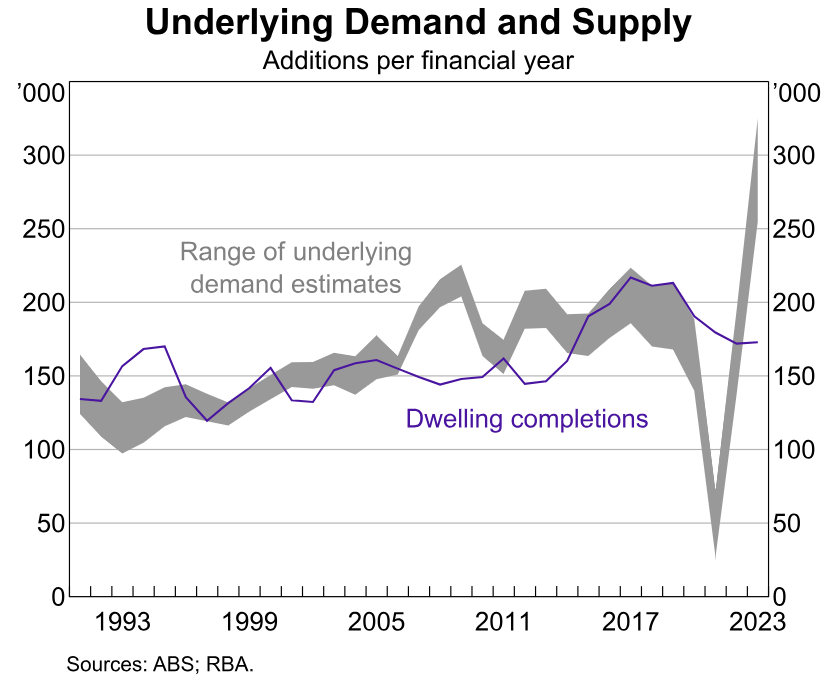

Hunter noted that “growth in demand is currently running well ahead of supply” and estimated that underlying housing demand is sitting somewhere between 260,000 to 320,000 homes per year:

As shown above, Australia’s housing market has experienced a structural undersupply for most of the period since net overseas migration was ramped-up from 2005.

The RBA’s estimate of underlying demand is also well above that of the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council’s (NHSAC) finding in its State of the Housing System 2024 report.

NHSAC estimated that underlying demand is currently around 230,000 and will later moderate to about 174,000.

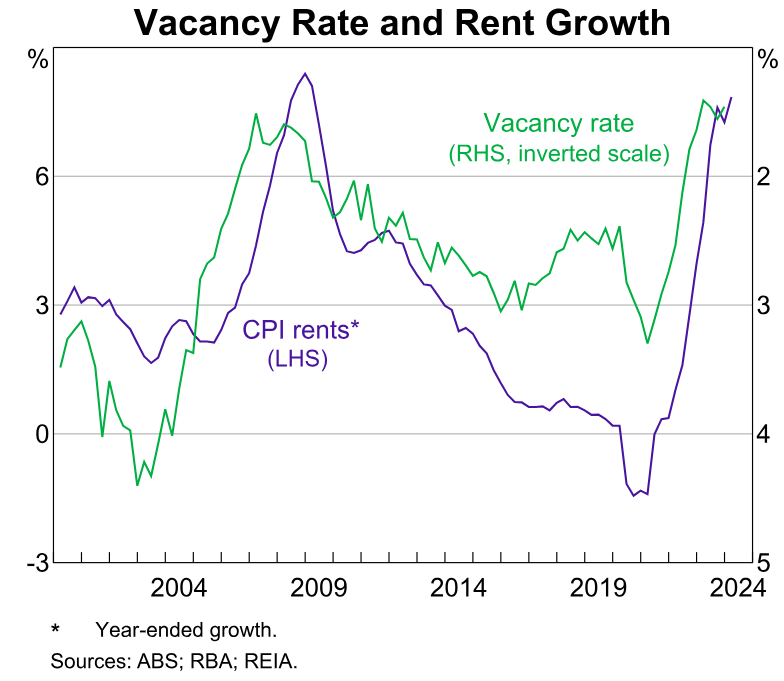

Hunter noted that the imbalance between housing demand and supply has driven down rental vacancy rates and driven up rental inflation:

She also noted that “the last couple of years has seen a perfect storm of constraints on activity. Materials, fixtures and fittings, and skilled labour were in short supply, and shipping delays significantly extended build timelines”.

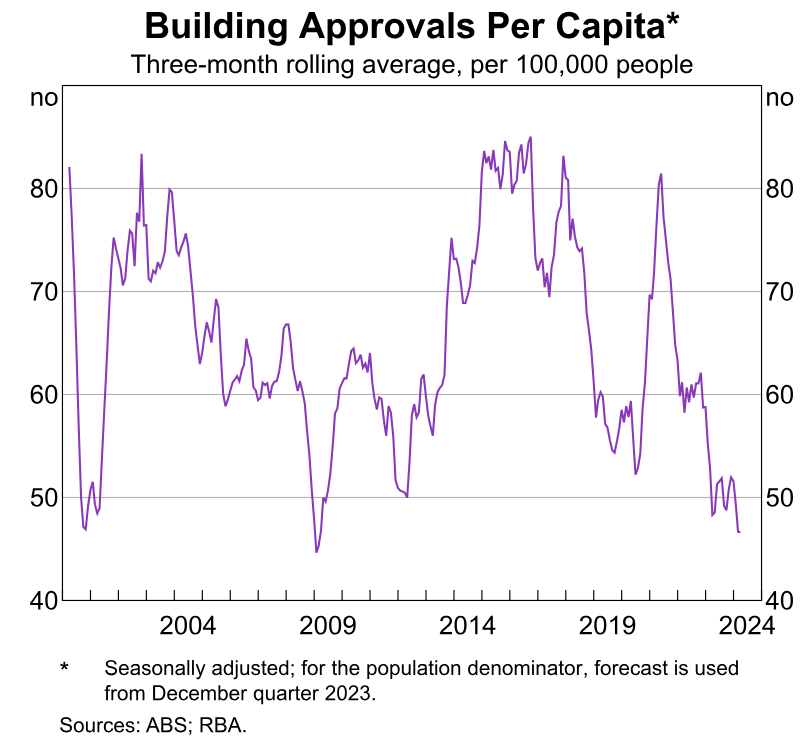

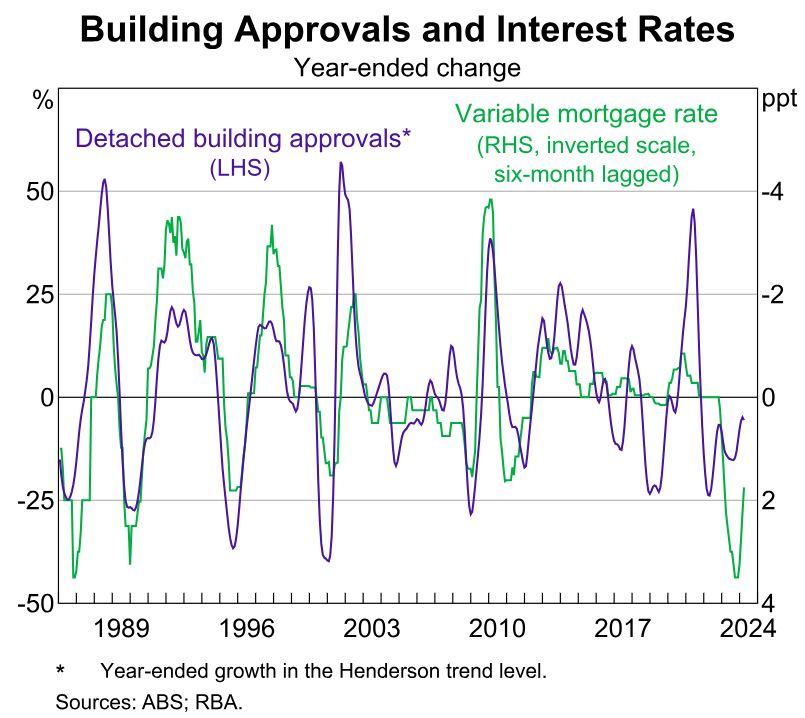

“The sector is now facing weaker demand – dwelling approvals per capita are sitting at decade-lows”.

“In other words, some market participants have delayed projects or decided not to begin because of the relatively high cost of building when compared with the project’s returns”, Hunter said.

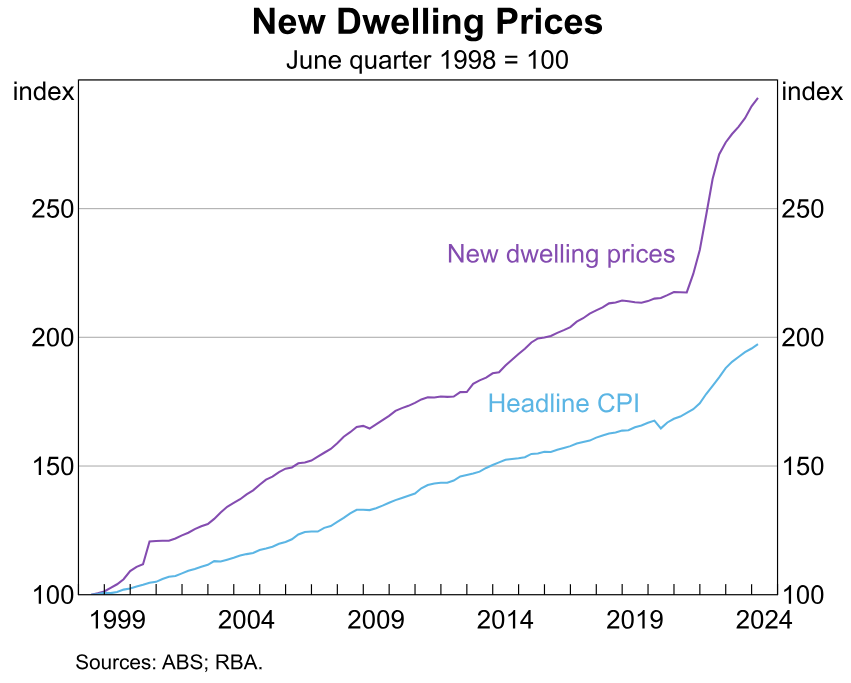

She also noted that costs have “risen sharply, and we do not expect them to fall back significantly”.

“Pandemic-related supply chain disruptions and competition for resources from other types of construction have pushed up prices significantly, by nearly 40% since late 2019”:

To add insult to injury, “many dwelling construction projects are funded by debt, and so higher interest costs will dampen the flow of new housing supply”:

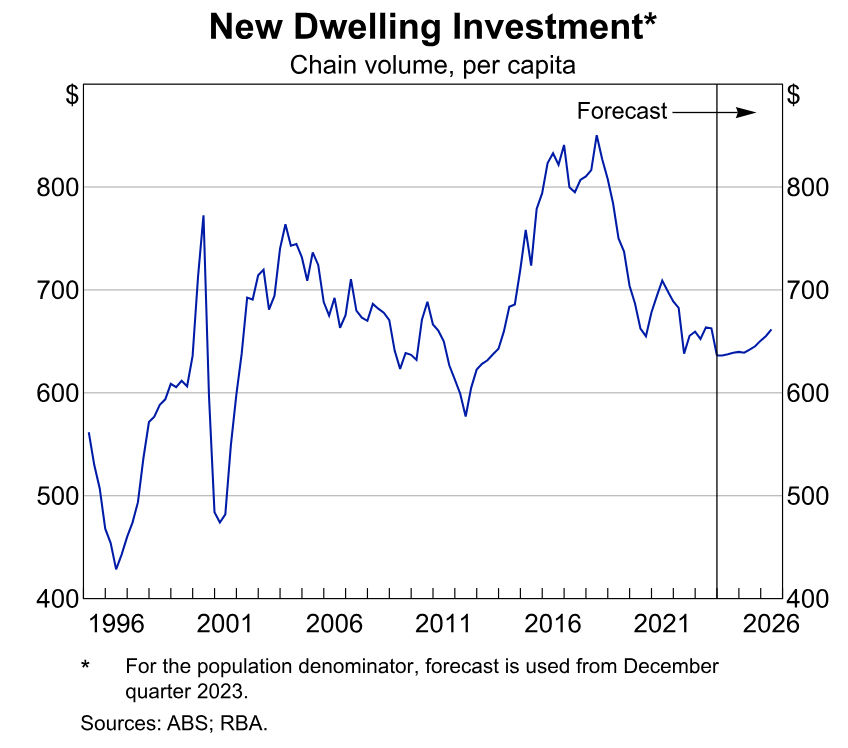

As a result, the RBA forecasts a prolonged period of low housing construction:

In turn, Australia’s housing crisis will drag on, according to Hunter:

“Demand pressure, and so upward pressure on rents and prices, will remain until new supply comes online”.

“We expect this response to take some time to materialise, given the current level of new dwelling approvals and the information from liaison that many projects are still not viable”.

“In the meantime, we expect residential construction activity to remain relatively subdued”.

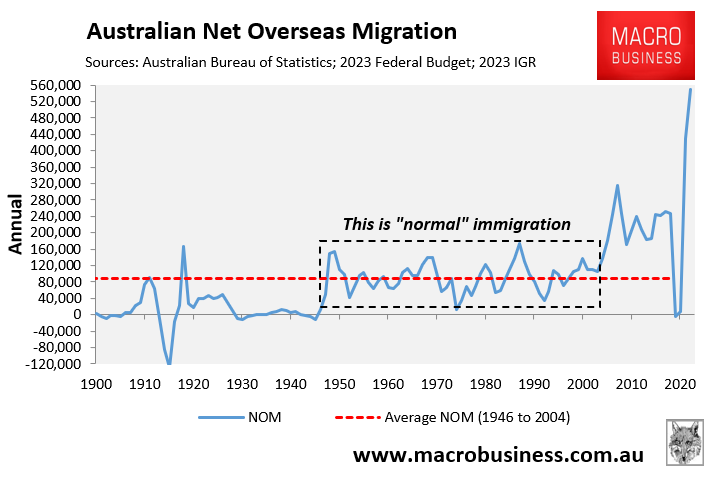

As usual, the RBA has treated the problem as a supply issue and has ignored the quickest, easiest, least expensive, and optimal solution of cutting net overseas migration to a level that is well below the nation’s capacity to build homes and infrastructure.

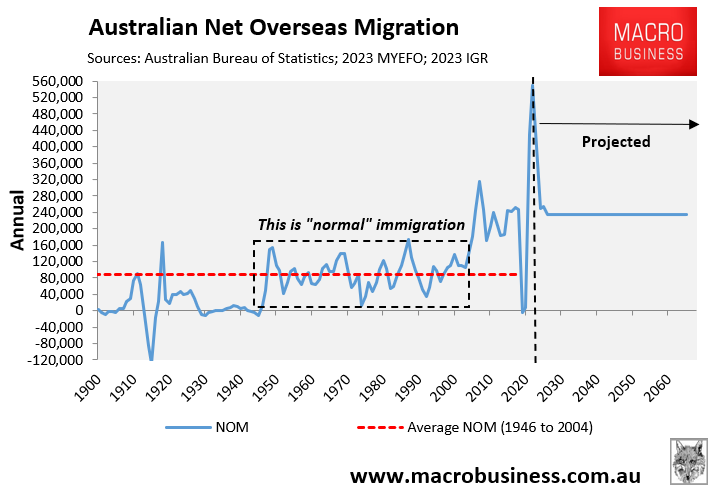

The latest Intergenerational Report’s net overseas migration projections are plotted below:

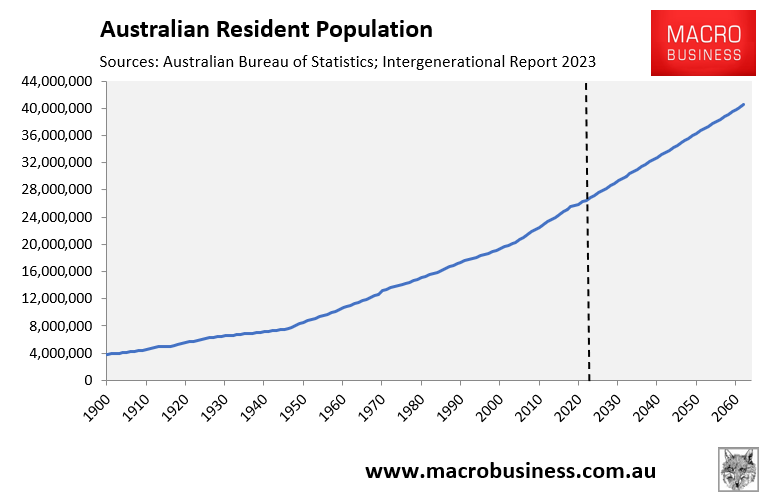

Under these projections, Australia’s population will balloon to 40.5 million people by 2062-63, which is a 13.5 million population increase on the current level:

That 13.5 million population increase is the equivalent of adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to Australia’s current population in only 39 years.

Australia will never build enough housing for that level of population increase.

Cut net overseas migration to historical levels of around 120,000 a year instead.