I noted last month how the composition and quality of Australia’s international student intake have dramatically changed over the past decade.

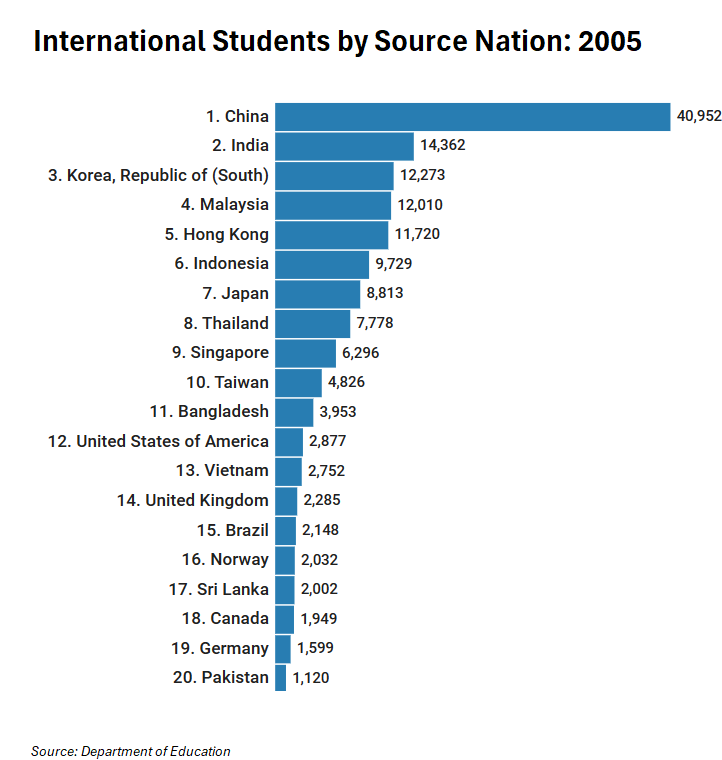

In January 2005, there were 173,787 overseas students studying in Australia.

As shown in the chart below, China (40,952) dominated enrolments, with India (14,362) in a distant second position.

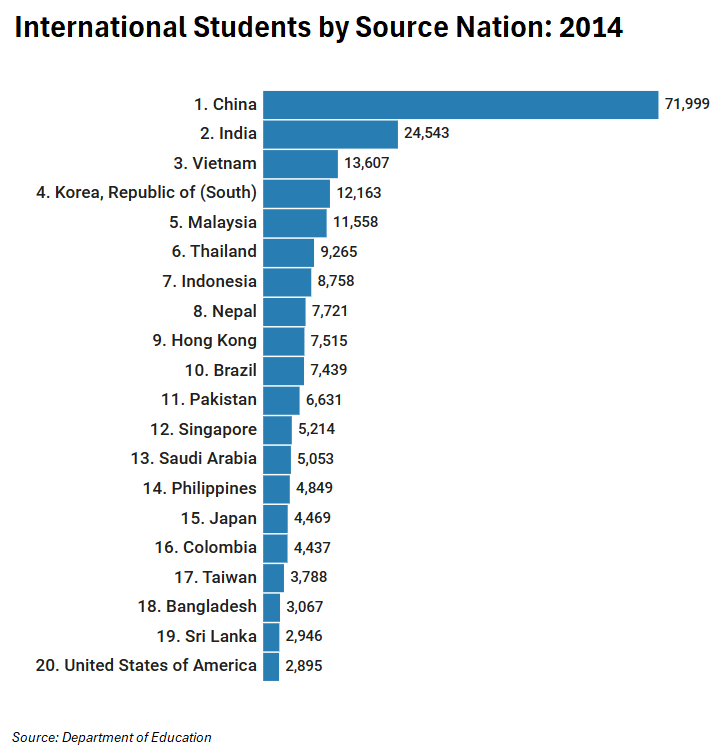

Nine years later, in 2014, Australia’s international student enrolments had climbed to 258,098, with China (71,999) still dominating enrolments and India (24,543) in a distant second position.

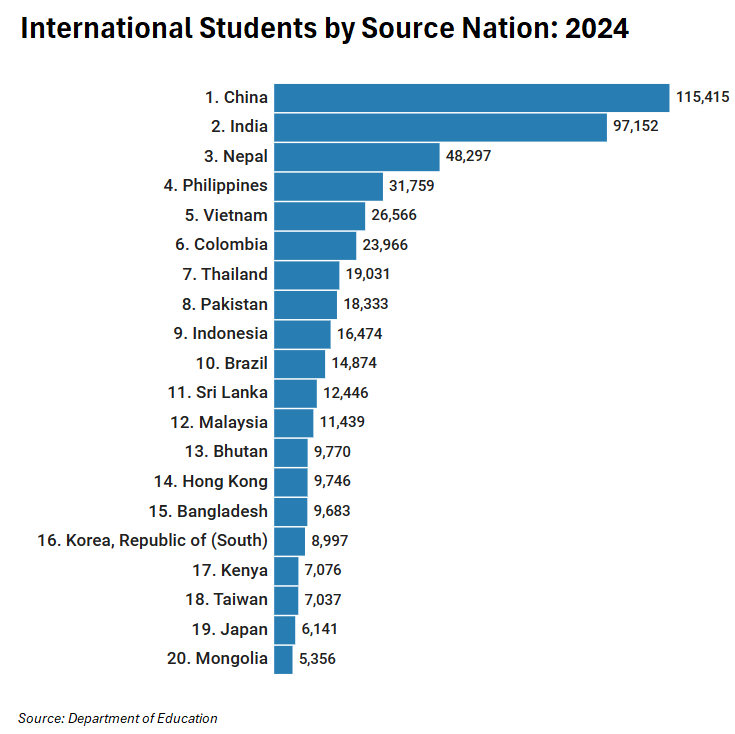

Fast forward a decade to January 2024, and there were 567,505 overseas students in Australia.

While China continues to have the most overseas students (115,415), the number of Indian (97,152) and Nepalese (48,297) students has increased dramatically:

This movement towards students from South Asia raises quality concerns in Australia’s overseas education sector.

A recent Navitas survey of study intentions discovered that students from South Asia and Africa choose a study destination based on their capacity to gain job rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency.

South Asia and Africa care about work and migration, not education quality.

In contrast, students from these two continents are least concerned about educational quality.

All source nations, with the exception of students from China and Europe, place a high value on opportunities to work while studying and post-study job privileges.

As illustrated in the following graphic, Australia has had the largest growth in student numbers from nations that support themselves through paid employment, whereas only one-fifth of Chinese students do the same:

As a result, the concept of international education ‘exports’ only truly applies to Chinese students, who typically pay their tuition and living costs in Chinese currency rather than work income earned in Australia.

As explained by Associate Professor Salvatore Babones in his latest book “Australia’s Universities, Can They Reform“:

“In reality, everyone (except perhaps the government and the universities) knew that many international students pay for their courses out of the proceeds of their work in-country, often working excessive hours under exploitative conditions, in violation of their visa terms”.

“This situation is especially common among South Asian students, and is reflected in the steep fall-off in South Asian student numbers when teaching moved online”.

“With prospective students unable to rely on employment income in Australia to support their studies, new commencements of Indian students at Australian higher education providers fell 65% between 2019 and 2021; for Nepali students, the decline was 37%; for Pakistanis, 45%; for Sri Lankans, 54%”.

“These countries are simply too poor to send large cohorts of international students to Australian universities based on family resources alone”.

“For many South Asian students, a student visa is a very expensive but thinly disguised work visa”.

The above analysis explains why international education is essentially a people-importing immigration industry rather than a legitimate education export industry.

Student visas are often disguised as low-skilled work visas.

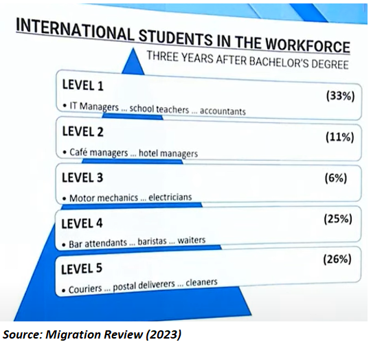

The same is true for post-study international graduates. The Migration Review reported that 51% of international graduates with a bachelor’s degree who had been in Australia for three years worked in low-skilled occupations:

With this background in mind, it was encouraging to read that Australia’s international education sector is inching back to being a genuine export industry.

As reported in The AFR, Chinese university students have been able to secure 97.2% of visa approvals compared to 83% across the board, despite high visa knock-backs.

However, visa approvals for applicants from Pakistan, Nepal, and India have fallen sharply, with Pakistan at 46.6%, Nepal at 60%, and India at 68.6%.

The latest migration policy changes have targeted non-genuine students and dishonest education agents and colleges, who have poached genuine students from respected universities and providers.

The worst regions include parts of India, Pakistan, and Nepal.

By contrast, Chinese university students, who mainly enrol in Group of Eight universities and leave Australia at the conclusion of their studies, are considered to be at low risk of abusing the visa system.

Let’s be honest for a moment. If work rights and permanent residency were scaled back, the numbers of students arriving from non-Chinese source nations would collapse.