Australia’s housing system is caught in a vicious cycle.

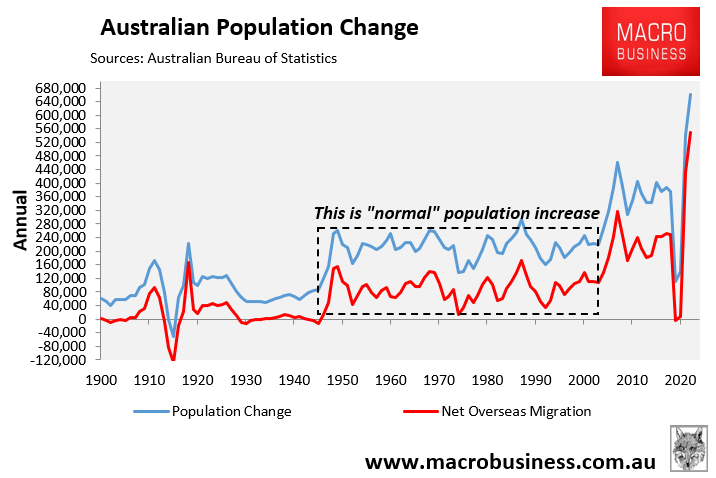

The federal government has locked in permanently high population growth via net overseas migration (NOM).

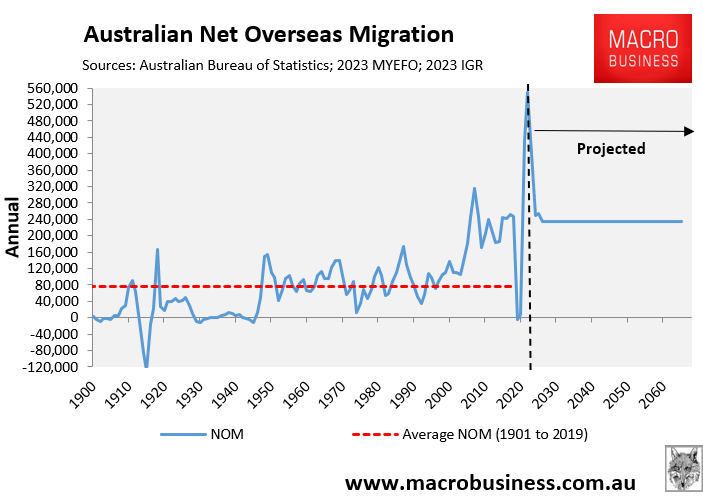

Even if the federal government is successful in lowering NOM to levels projected in the latest Intergenerational Report, illustrated in the next chart:

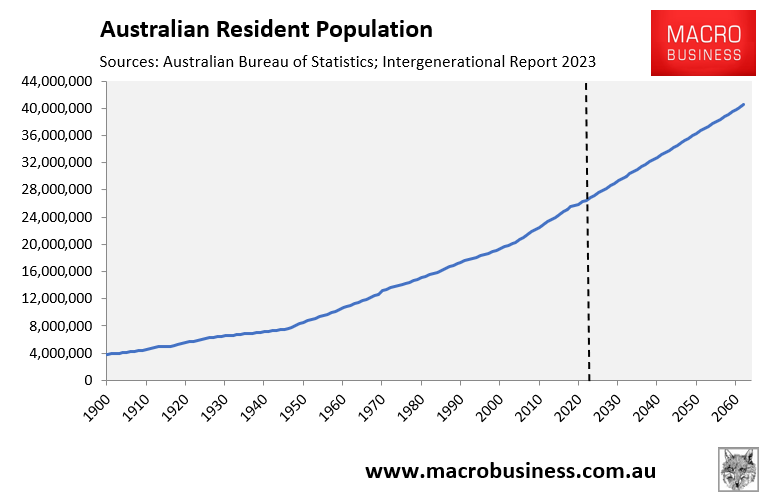

This would see Australia’s population surge to 40.5 million people by 2062-63, which is a 13 million population increase on the current level:

This level of population increase is the equivalent of adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane worth of population in only 39 years.

Such a massive population increase will obviously necessitate massive expenditure on new infrastructure; otherwise, the economy, productivity, and living standards will become crush-loaded.

However, building infrastructure has become increasingly expensive due to the requirement to retrofit our major cities for greater population densities and the dis-economies of scale associated with tunnelling and land buybacks.

Large-scale population growth also requires a corresponding build-out of homes and associated local infrastructure (e.g., local roads, sewerage, and water systems) to accommodate the additional people.

However, the housing sector is struggling to compete with the public infrastructure sector when it comes to materials and talent, with the latter sector offering sub-contractors higher prices and less risk.

In turn, this competition is harming the construction of new homes and apartments, with new figures from the Housing Industry Association (HIA) revealing that cost pressures in areas such as labour and concrete will delay an expected pick-up in the development of high-rise apartment building projects “by at least 12 months”.

“In the absence of that type of volume we are going to see extraordinary increases in rental prices”, warns HIA chief economist Tim Reardon.

The states have flagged their intention to slow down their spending on infrastructure, but the resultant release of labour will need to happen at the same time as builders and developers are ready to start on new projects if it is to have a positive impact on housing construction.

“Many high-rise residential developments are stalled or not going ahead due to the high costs of construction relative to apartment sale prices and capacity constraints in the construction industry”, the RBA said in its latest Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP).

“The cost and availability of labour remains a challenge, particularly for high-density projects that compete with the large volume of infrastructure projects for similar skills”, the SoMP said.

High levels of immigration have ultimately caught Australia’s housing system in a pincer.

Australia is unable to build enough housing and infrastructure to accommodate the ballooning population. Fulfilling one objective (e.g., building infrastructure) negatively impacts the other (e.g., building homes).

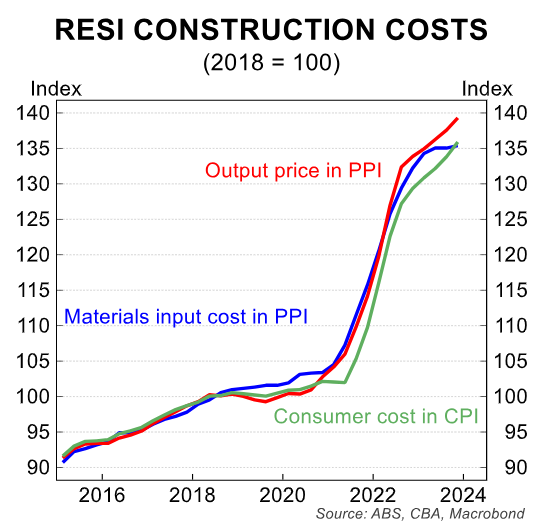

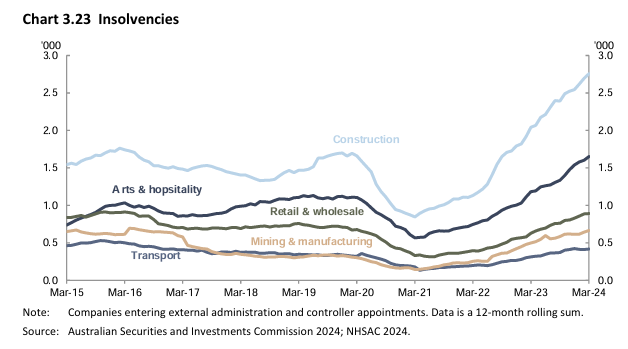

This is especially the case in the era of elevated construction costs post-pandemic, alongside the widespread collapse of construction firms.

“Rising insolvencies and diminishing capacity has fuelled further construction cost escalation, and while this has not been at the peak of 2022, it has continued to damage and reduce the margins for project viability”, Arcadis’ head of cost and commercial management, Matthew Mackey, says.

“While the industry grapples with higher construction costs, projects have stalled amid damaging confidence levels”.

The solution is to dramatically slow net overseas migration to a level that is below the nation’s capacity to build new homes and infrastructure.

Slowing the increase in population to sustainable historical levels of around 220,000 people a year will enable Australia to supply enough housing and infrastructure.