Great piece here from Bloomie:

China’s first-quarter 5.3% growth handily beat expectations and Beijing’s own target of “around 5%.” But if you ask households, companies and even the taxman, the reality on the ground feels a lot less rosy.

By the end of 2023, only 9.5% saw good job prospects, according to the central bank’s latest urban depositor survey. Preparing for rainy days, households added 8.6 trillion yuan ($1.2 trillion) in their savings in the first quarter, prompting some banks to discontinue long-term fixed-income offerings to protect their margins. The CSI 2000 Index, whose small-cap companies are more sensitive to business cycles, is down 20% for the year. Meanwhile, as of February, government fiscal revenue fell 2.3% from a year ago.

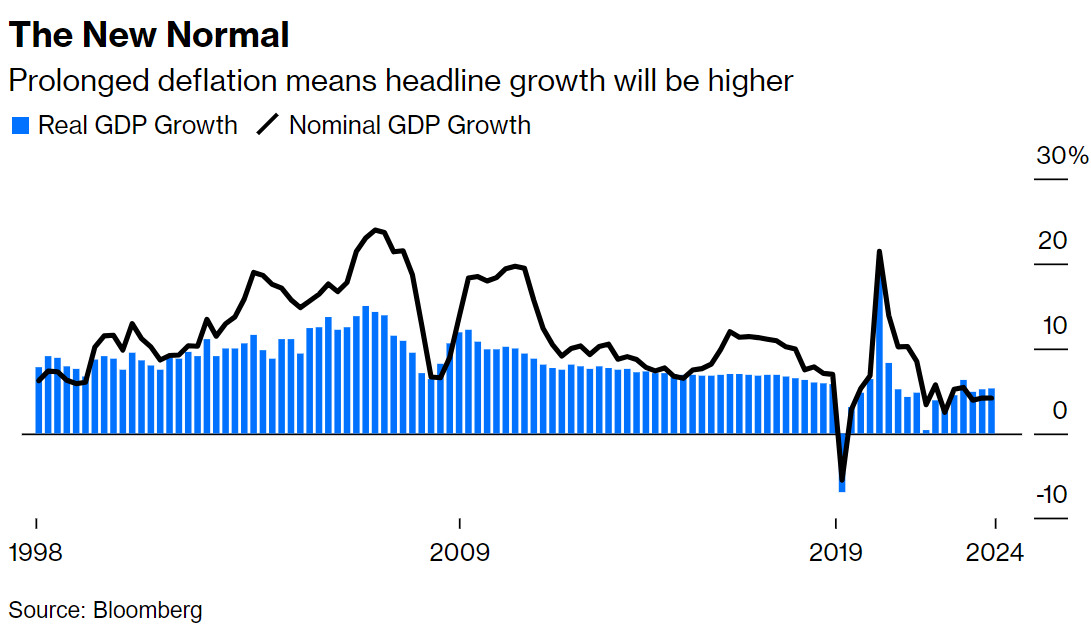

I have noted China’s first trick for the past year. This is part of the regulation of GDP calculations everywhere. The national accounts should measure volumes, not price movements, so they include a measure of inflation—called the deflator—to remove price distortions. In Q1, nominal GDP was only 4.2% then, owing to powerful deflation, the deflator added 1.1% for 5.3% GDP:

The second trick is to use only one of the accepted GDP matrixes.

In Australia, we have three styles of GDP – production, expenditure and income – each measures activity slightly differently, and the ultimate number is the average of all three.

On the other hand:

The second factor has to do with how China calculates quarterly GDP. It uses a so-called production account, which prioritizes the value-add of each industry and brushes away end demand.

God only knows how China adjusts its production account to shifts in consumption; there must be something, but, at minimum, this is opaque and opens the opportunity for manipulation.

There is also the issue of how China accounts for misallocated capital. It doesn’t write down bad investments, which it is full of.

Then, there is the implicit observation that China issues its national accounts less than two weeks after the end of each month. It takes everybody else about ten times as long.

How does the NBS measure China’s enormous, seething, teeming population so precisely, so fast? It’s made up.

The NBS does make revisions, so the ultimate trend data is better, but anybody taking Chinese growth numbers at face value believes in Santa Clause.