By Gareth Aird, head of Australian economics at CBA:

Key Points:

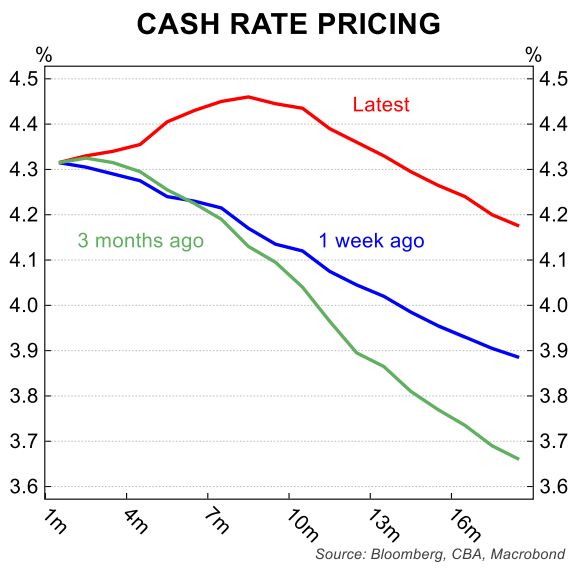

- The Australian Q1 24 CPI came in stronger than we forecast. As a result we shift our central scenario for the RBA to commence an easing cycle to November 2024 (from September 2024 previously). And we now expect only one 25bp interest rate cut in 2024 (compared with 75bp of easing previously).

- The near-term risk sits with an interest rate hike. But we expect the RBA to be on hold over the next six months given the economy is still contracting on a per capita basis, inflation is forecast to fall further and the labour market is anticipated to loosen.

- Monetary and fiscal policy are working in tandem. But incredibly strong net overseas immigration has put upward pressure on some components of the CPI basket. This has made the RBA’s task of returning inflation to target more difficult.

- As a consequence, monetary policy is now likely to stay at a restrictive setting for longer.

- We now see a more elongated and conservative easing cycle than previously expected. Our base case sees the cash rate gradually cut from November 2024 to reach 3.10% at end-2025 (a level we believe is just above neutral).

- The RBA Board may restore its hiking bias at the upcoming May Board meeting. But on balance we expect an ‘on hold’ decision to be accompanied by a neutral bias, in line with the policy decision and Statement from the March Board meeting.

Overview:

In October 2023 we wrote, “the massive lift in population has contributed to a greater increase in some components of the CPI basket than would have otherwise been the case – particularly rents, which have risen very significantly over the past year. There is a risk that the tightening cycle is extended if Australia’s population continues to swell at its current rate. In addition, it could mean interest rates stay higher for longer, which delays the start of an easing cycle”.

That risk looks to have materialised in the latest inflation figures. And the commencement of an easing cycle is likely to be delayed.

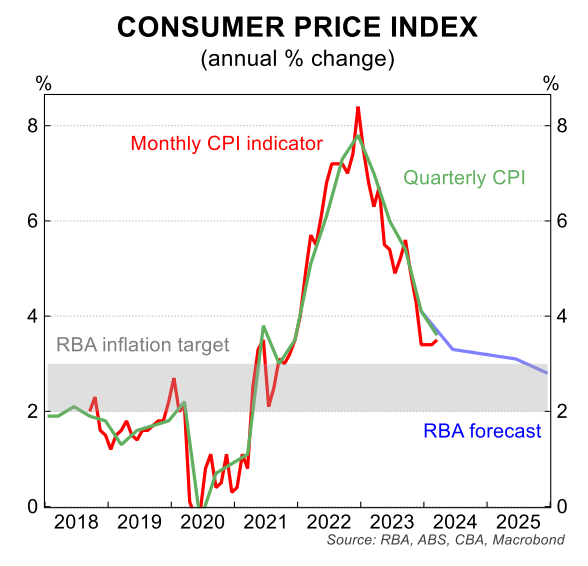

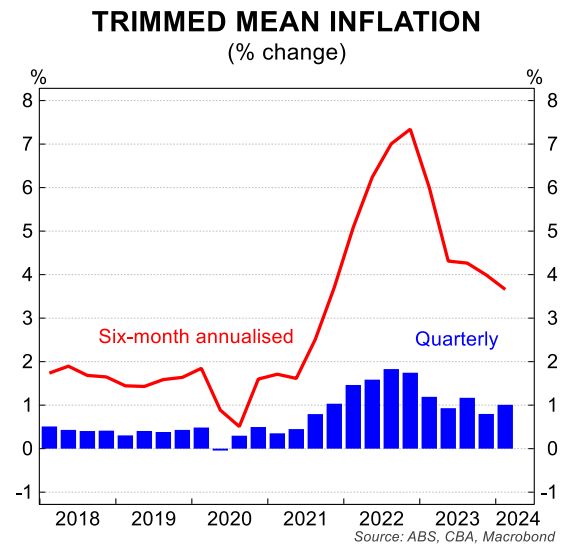

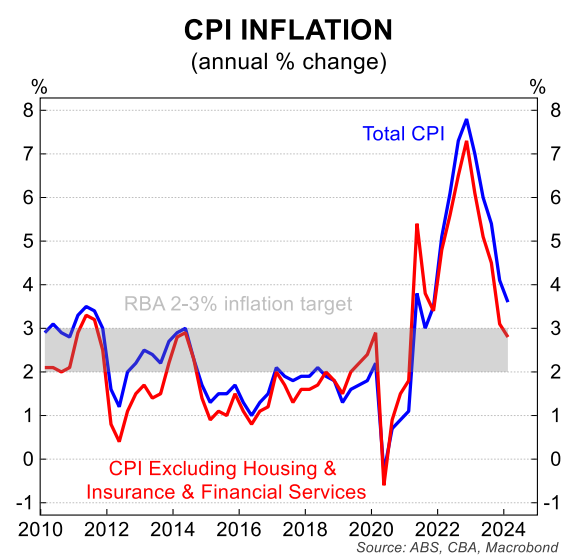

The Q1 24 CPI was an unwelcome set of numbers. Both headline and underlying inflation were stronger than we and the majority of the forecasting community expected.

The inflation print was also a little firmer than the RBA anticipated based on their latest forecasts from the February Statement on Monetary Policy (SoMP).

To be clear, the news was not all bad. Both the annual rate of headline and underlying inflation fell in the March quarter.

Headline inflation declined from 4.1% to 3.6%. And trimmed mean inflation eased from 4.2% to 4.0%. But the quarterly pulse of inflation firmed following a lower-than-expected Q4 23 outcome.

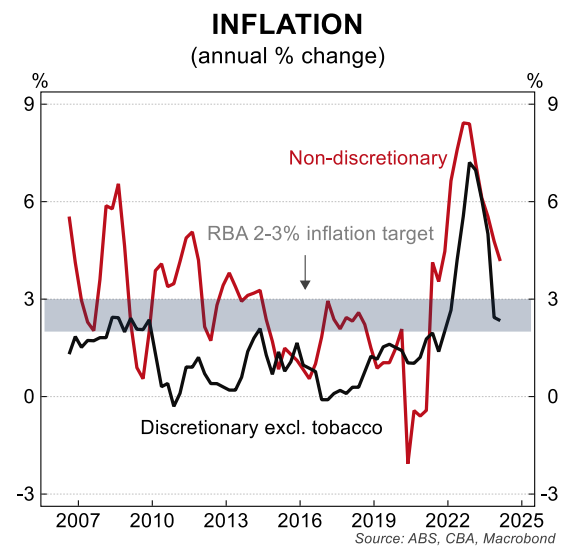

The RBA has been successful in bringing down discretionary inflation. But dropping non-discretionary inflation is proving to be a more difficult challenge.

We believe that incredibly strong population growth, driven by net overseas immigration, has put upward pressure on some important components of the CPI basket; most notably the housing-related components. As a result, demand is stronger and so inflation is falling less quickly than otherwise.

The upshot is the monetary policy will need to stay at a restrictive setting for longer to bring inflation back towards the mid-point of the RBA’s target band.

For context, we assess the neutral cash rate to be in the 2.5-3.0% range. So we consider a policy rate above 3% to be restrictive in Australia.

The recent inflation data coupled with a lower unemployment rate than we anticipated at this juncture means we push back the timing of our base case for the RBA to commence an easing cycle.

We also shift our central scenario for the timing of rate cuts in 2025.

Our base case now sees the RBA commence an easing cycle in November 2024 (from September 2024 previously).

Our updated profile has one 25bp interest rate cut in 2024 that would deliver an end year cash rate of 4.10%. We now look for 100bp of easing in 2025 and have pencilled in one 25bp rate cut in each quarter over 2025.

We favour the meetings that align with the quarterly SoMP publication (i.e. February, May, August and November). Such an outcome would see the end-2025 cash rate at 3.10% (compared with our previous call of 2.85%).

Given our estimate of the neutral cash rate, monetary policy remains restrictive through 2024 and 2025 on our forecast profile.

Our expectation for below-trend economic growth to continue over 2024 means that the labour market will further loosen and wages pressures will moderate. This will help to drag inflation back to the RBA’s target band.

Notwithstanding, the disinflation process is likely to take a little longer than we previously anticipated due to very strong population growth continuing to put upward pressure on some non-discretionary components of the CPI basket.

Non-discretionary inflation is too high:

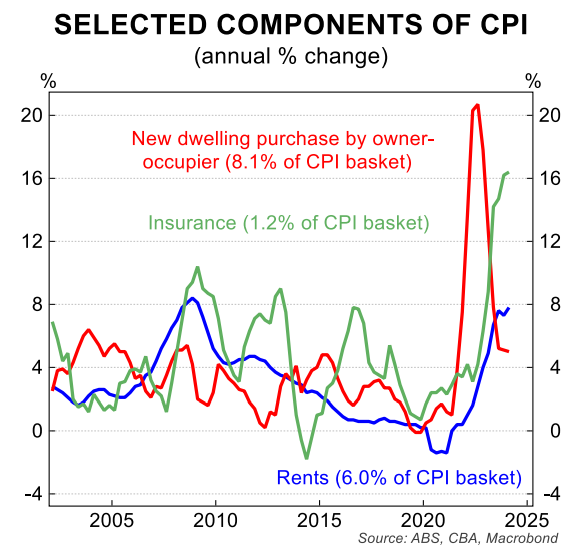

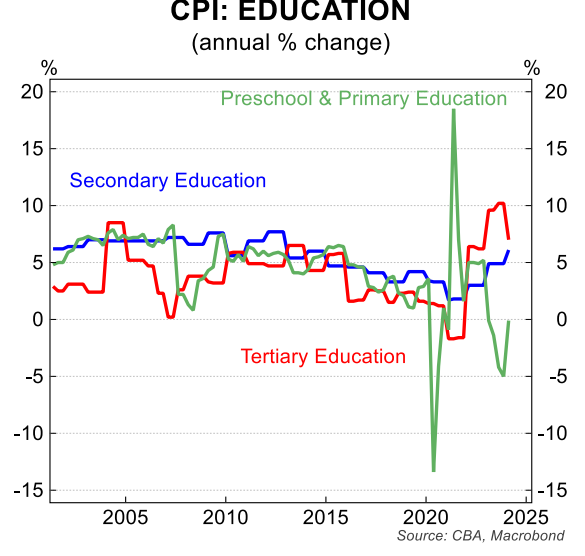

Non-discretionary inflation remains elevated. It has primarily been a tale of four expenditure items; the cost of building a home (good), rent (service), insurance (service) and education (service). Three of these items are housing related.

Monetary policy has not been able to put downward pressure on these expenditure items. More specifically:

(i) The cost of building a home has risen sharply because of a lift in labour costs and energy-intensive materials. Ongoing capacity constraints in the construction space, in part because of big public works programs to keep up with strong population growth, have pushed up the cost of home construction.

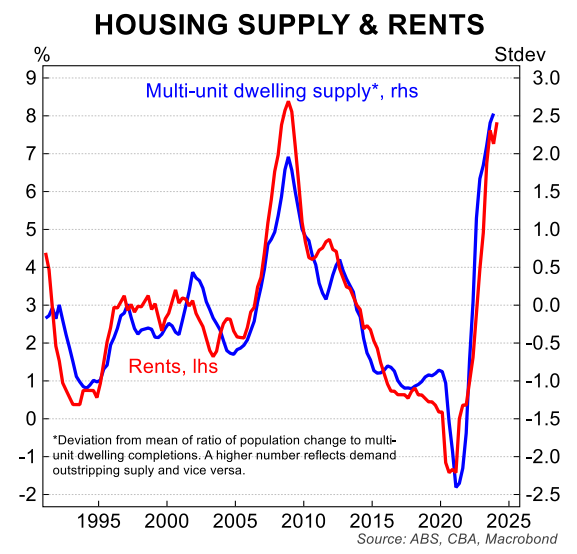

(ii) Rental inflation has been driven higher by the large mismatch between the underlying demand for housing (i.e. very strong population growth) and constrained growth in home supply. Rental markets are extremely tight across the capital cities and vacancy rates are at or near record lows. Commonwealth rent assistance has lowered rental price inflation a little, but it is still running well ahead of the overall pace of consumer price inflation.

(iii) Insurance prices have been driven sharply higher by a large increase in premiums for house insurance. The big lift in the cost of building a home over the past two years as well as natural disaster costs have generated a commensurate lift in insurance premiums. As the RBA Governor said in February, “the insurance sector has its own issues going on and there’s not a lot that monetary policy can do about that …that’s much more a matter for the government”. We completely agree.

(iv) Education prices recorded their largest rise since 2012 in Q1 24 (this covers preschool, primary, secondary and tertiary education). Fees are collected once a year at the beginning of the school year. According to the ABS, the strong 5.2%/yr rise in Q1 24 was driven by higher primary and secondary school fees, as well as tertiary education following the indexation of higher education course fees. The indexation is based on recent prior inflation outcomes, which were significantly higher than the current rate of inflation. The upshot is that the indexation rate in Q1 25 will be materially lower than the one applied in Q1 24. It is worth noting that preschool, primary and secondary education are classified as non-discretionary by the ABS, while tertiary education is considered discretionary.

Discretionary inflation has fallen swiftly:

Monetary policy is much more effective on the discretionary components of the CPI basket. And the data indicates that discretionary inflation has receded just as quickly as it went up. Prices for non-essential items made a sharp levels adjustment upwards when demand in the economy was strongest. But the lift in prices has not continued as demand has softened.

The evidence of softening consumer demand is in the spending data. As the national accounts indicate, spending per capita has declined materially over the last five quarters (latest data to Q4 23). Our internal data indicates that the volume of spending per capita continued to contract in Q1 24. We forecast real household consumption per capita will continue to fall over the remainder of 2024.

Indeed, household consumption per capita in Australia looks vastly different compared to the US. Consumer spend per capita has expanded solidly in the US over the same period it has contracted in Australia.

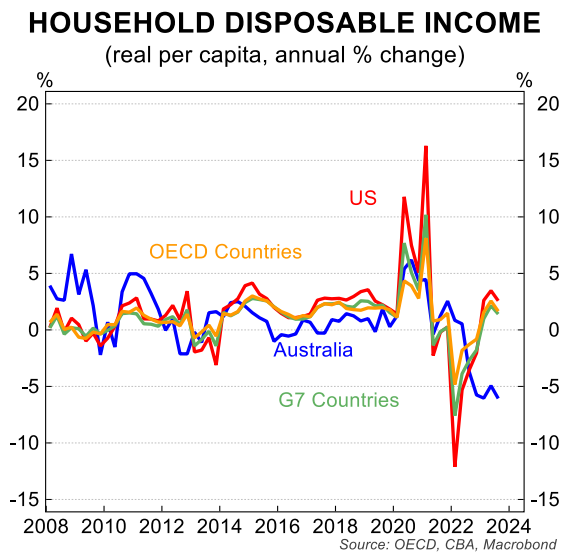

The reason is that real household disposable income per capita has contracted sharply in Australia due to negative real wages growth, rising dwelling interest paid and taxes paid. In contrast, real household disposable income per person has risen over the past year across most OECD countries, particularly in the US.

As we covered previously, the transmission of monetary policy in Australia to the household sector and by extension the broader economy is much more direct and potent than in most other major jurisdictions, particularly when compared to the US.

Discretionary inflation is likely to fall further as Australian households continue to tighten their belts. This in turn will see the labour market loosen and wages pressures dissipate.

As wages growth eases, it will put downward pressure on cost push inflation in the services sector where wages growth is generally the dominant driver of price rises (note that dynamic is not applicable to rents, which are considered a service).

Immigration:

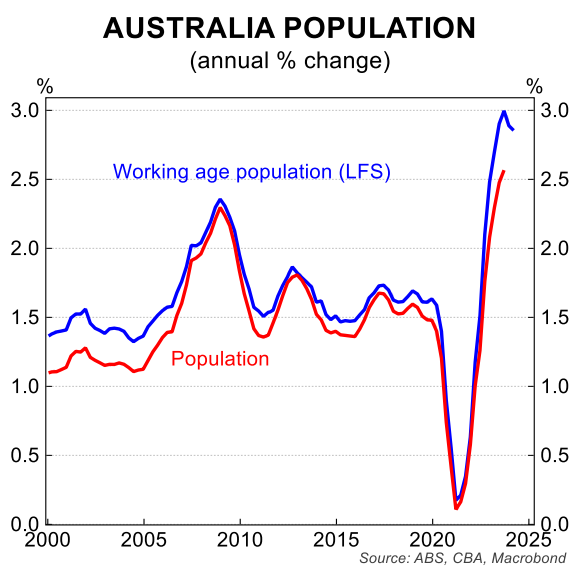

The surge in Australia’s population over the past eighteen months has been extraordinary. It has been significantly stronger than the Government forecast. For context, growth in the working age population from the labour force survey was 2.9%/yr in March.

The facing chart highlights the massive recent lift in the population compared to pre-pandemic levels.

The surge in population growth has boosted aggregate demand in the economy. In turn this has somewhat masked the per capita decline in real consumer spending.

More importantly from a monetary policy perspective, there are implications for inflation.

Higher than expected immigration is alleviating wage pressures in some industries that had been experiencing significant labour shortages. In turn that should dampen inflation outcomes over the medium term as growth in input costs slow (labour is a key input in the cost of production, particularly in the services sector).

But in the short run we believe the rapid increase in population contributes to a firmer inflationary pulse. The RBA has not been as vocal about the impact of strong population growth on inflation as the RBNZ. But in the April 2023 Board Minutes it was stated that, “members noted that the net effect of a sudden surge in population growth could be somewhat inflationary for a period.”

Since then population growth has continued to run at an incredibly strong rate.

In summary, fiscal and monetary policy are broadly working in tandem in Australia when assessing the stance of fiscal policy from a budgetary perspective. But the policy decision to have very strong net overseas immigration in the short run has put upward pressure on some components of the CPI basket that has made the RBA’s task of returning inflation to target more difficult.

Unemployment will lift and inflation will continue to fall:

Despite the impact that strong immigration has on inflation in the short run, we believe that inflation will continue to ease from here and the labour market will loosen.

The process of labour market loosening to date has taken longer than we anticipated given very weak economic growth. But it is nonetheless happening.

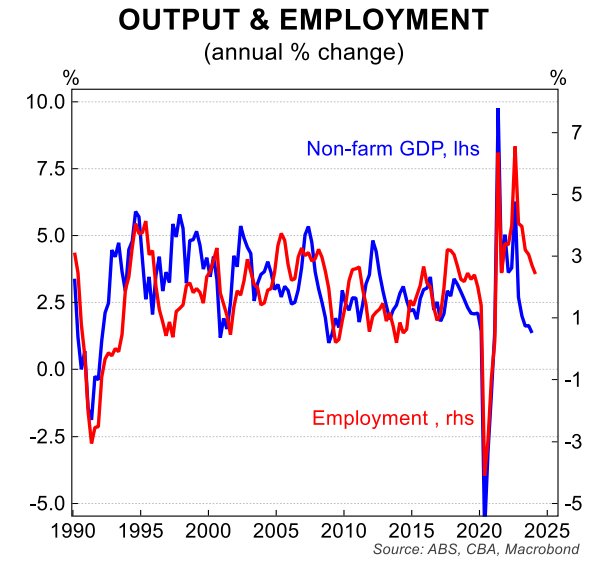

Indeed there is typically a lagged relationship between employment growth and GDP growth. The strongest correlation between quarterly GDP and employment growth occurs after two quarters.

The upshot is that we remain relatively confident that employment growth will continue to moderate from here. In turn, that will see the unemployment rate move higher. That is our base case. See here for our take on the latest labour market data.

More organic tightening in the pipeline:

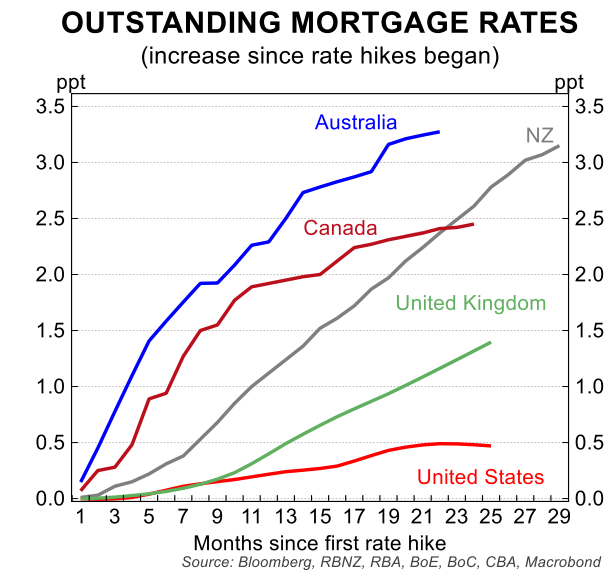

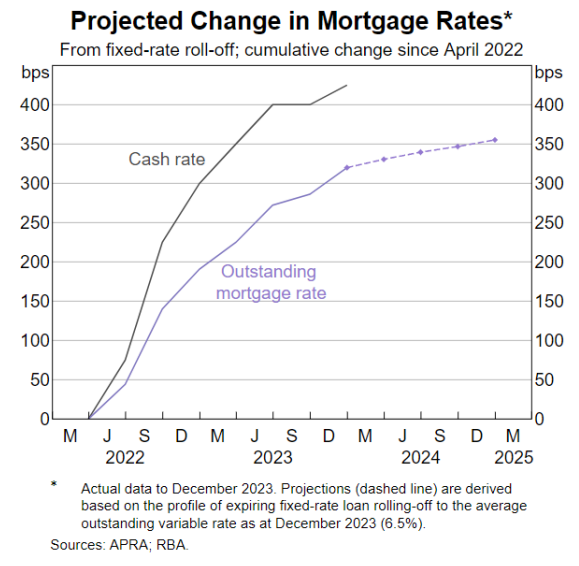

The average outstanding mortgage rate has moved materially higher in Australia compared to many other countries, particularly compared to the US.

The average outstanding mortgage rate will continue to increase further as the remaining loans on low fixed rates expire and reprice at much higher interest rates.

According to the RBA, there remains a substantial share of low-rate fixed-rate loans – around 35% of the stock of fixed-rate loans that was outstanding in December 2022 – that will expire over 2024. Under the assumption that these fixed-rate loans reprice to the current outstanding variable rate, the average outstanding mortgage rate is projected to increase by an additional 35bp between December 2023 and December 2024.

This means there is still ongoing tightening to hit the Australian household sector over coming quarters. This will result in mortgage repayments as a share of household income continuing to lift. And in turn this will put downward pressure on aggregate demand and by extension inflation.

The May RBA Board meeting:

The RBA Board meets next week with the policy decision announced on Tuesday 7 May. We expect the cash rate will be left on hold.

The latest inflation data was a little firmer than the RBA anticipated. But we don’t think it was sufficiently strong for the RBA to tighten policy again.

The RBA Board moved from a tightening bias in February to a neutral stance in March. And the March Board Minutes indicated that the Board did not consider the case to raise the cash rate at the March meeting.

Since the RBA commenced its tightening cycle in May 2022 the Minutes have canvased what the Board considered at each policy meeting.

More specifically, at each meeting that the Board decided to leave the policy rate unchanged the case to raise the cash rate was also considered. But in the March Minutes it was apparent that the Board did not discuss the case to tighten policy in March.

The RBA Board may consider the case to raise the cash rate in May. In which case the Board may opt to revert to an explicit tightening bias in the Statement accompanying the decision. But it’s probably not a necessary move given the current wording in the Board’s neutral bias gives the RBA full optionality around its next policy move.

Recall that the March Statement noted, “the path of interest rates that will best ensure that inflation returns to target in a reasonable timeframe remains uncertain and the Board is not ruling anything in or out”.

The RBA will publish updated forecasts next week in the May SoMP. The RBA may make a small upward revision to their inflation profile in 2024. But we expect the forecast for inflation to return to the mid-point of the target band by Q2 26 will be retained.