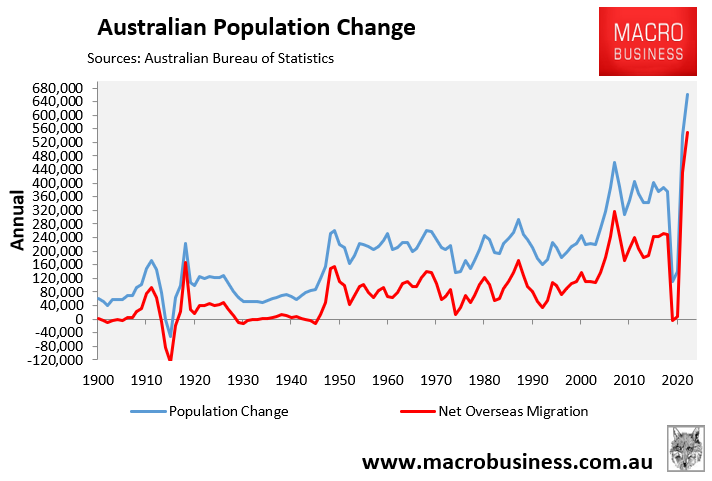

Last month, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the official population data for the September quarter of 2023, revealing that Australia’s population increased by an astounding 660,000 people over the year, driven by a record net overseas migration (NOM) of 549,000.

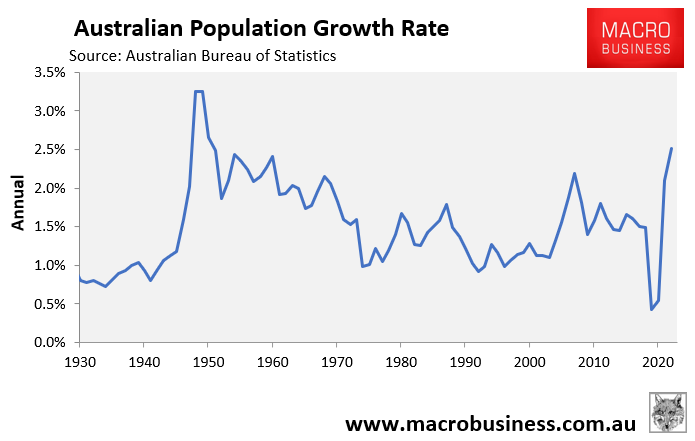

In percentage terms, Australia’s population increased by 2.5%, the fastest growth rate since 1952, during the postwar migration boom.

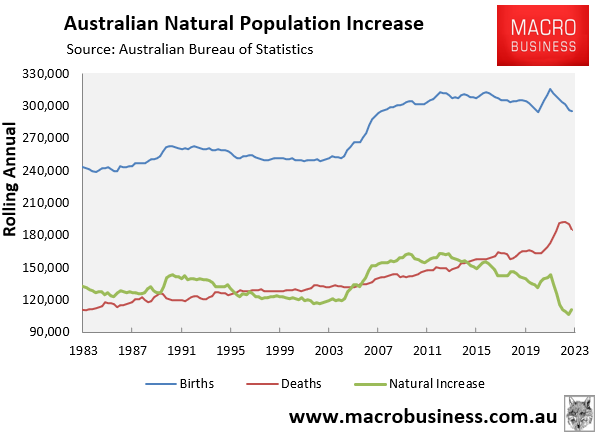

Meanwhile, Australia’s natural population gain was a historically low 111,000 in the year to September 2023, owing to a spike in mortality, most likely caused by the baby boomers’ ageing and the effects of the pandemic.

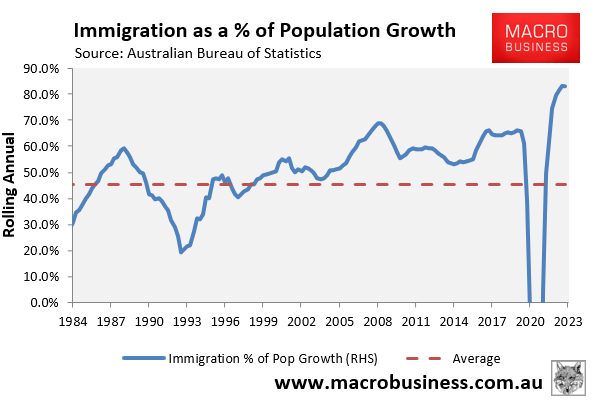

As a result, NOM’s share of Australia’s population growth stayed at an all-time high of 83% in the September quarter of 2023.

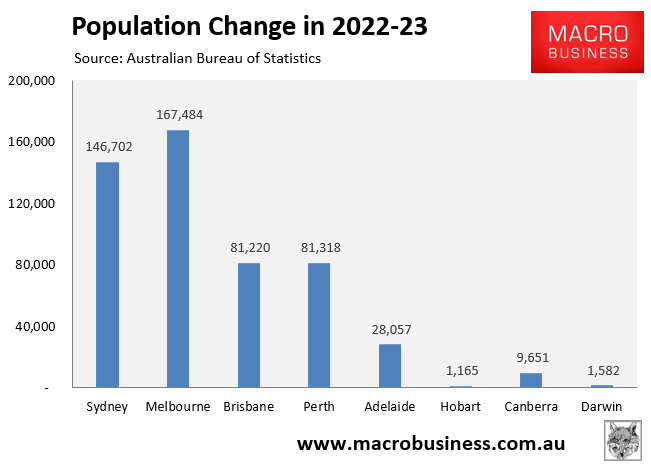

Separate annual data released by the ABS for the financial year 2022–23 revealed that Australia’s capital cities expanded by a record 517,000:

Last year, Melbourne (167,500) led the nation in population growth, followed by Sydney (146,700).

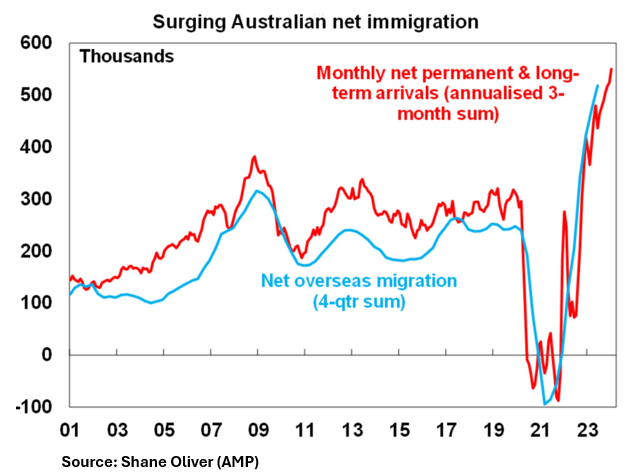

The ABS’ monthly permanent and long-term arrivals data are a good approximation for the official quarterly NOM.

Annual net permanent and long-term arrivals reached a new high in January 2024, implying that Australia’s official NOM and population growth will have accelerated further in the December quarter of 2023.

In its December Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Update (MYEFO), the Albanese government forecast that Australia’s NOM will fall to 375,000 this financial year, marking the second-highest annual NOM in the country’s history.

However, given the acceleration of NOM in the September quarter and the stronger-than-expected net permanent and long-term arrivals statistics through January, Australia should expect much greater NOM this financial year than the government estimated.

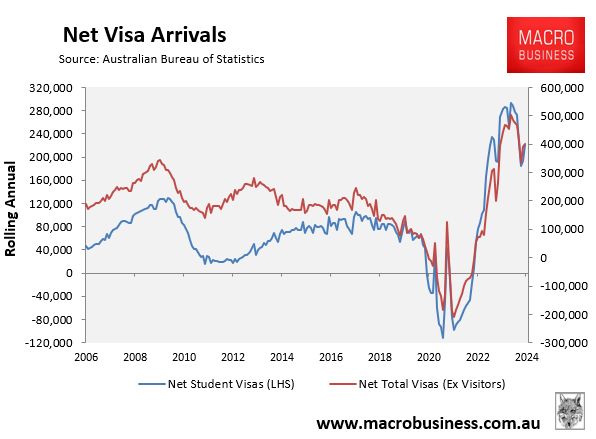

The good news is that visa data indicates that NOM is at or near its peak.

According to the ABS, there were 402,000 net visa arrivals (excluding tourists) in the year to February 2024, a decrease from a recent high of 503,000.

International students, who fell to 221,000 in the year to February from a recent high of 294,000, have led this decline in visa entries.

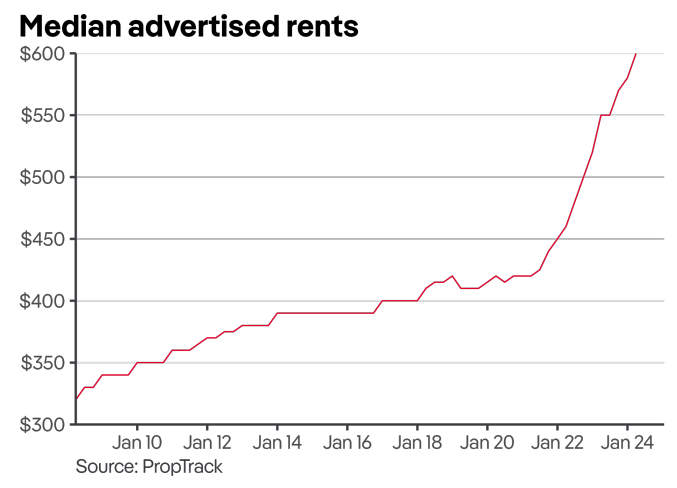

Australian renters are getting smashed:

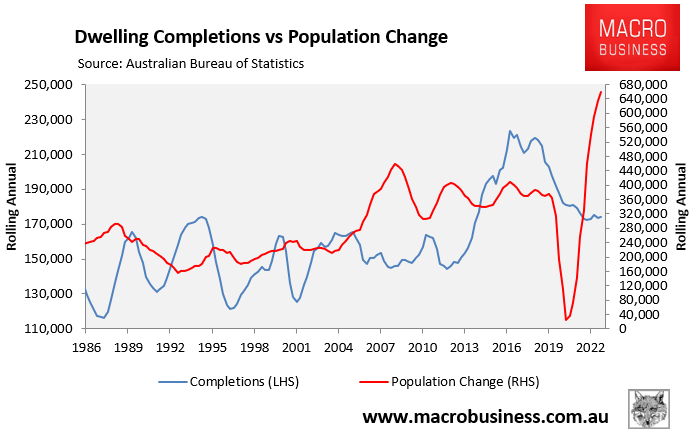

The migrant surge has severely impacted the nation’s rental market because the population growth coincided with a decade-low fall in homebuilding.

According to the ABS, Australia’s housing stock increased by only 155,600 homes (net of demolitions) in the year to September 2023, despite a 660,000 population increase.

As a result, Australia added only one new dwelling per every 4.24 additional residents. This explains why the nation’s rental vacancy rate has fallen to a record low of just 1%.

PropTrack reported that median asking rents in Australia have risen by 38% since the start of the pandemic, with almost all of this surge occurring when the federal government opened the international border for migrants in late 2021.

With Australia’s net overseas migration and population growth projected to stay historically high for the foreseeable future, and the rate of home construction expected to reduce further, the housing situation in Australia will remain distressed.

As a result, Australian tenants should brace for additional rental market tightening and continued high rental inflation.

Australia needs a smaller and more targeted migration system:

Few people would deny that Australia’s immigration volumes are excessive.

While migrants fill important labour market gaps throughout the economy, the sheer volume of arrivals has put undue strain on the housing market and the country’s infrastructure.

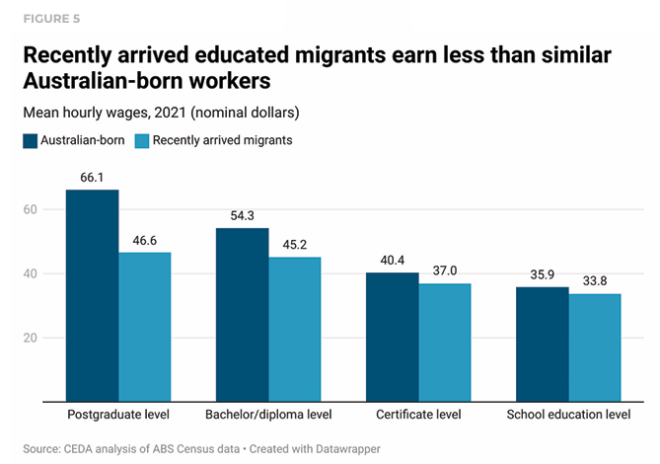

According to a report released last month by the Committee for Economic Development Australia (CEDA), “recent migrants earn significantly less than Australian-born workers”, and “migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”, earning more than 10% less than Australian-born workers on average.

The CEDA analysis also found that recent skilled migrants have higher unemployment rates than Australian-born residents.

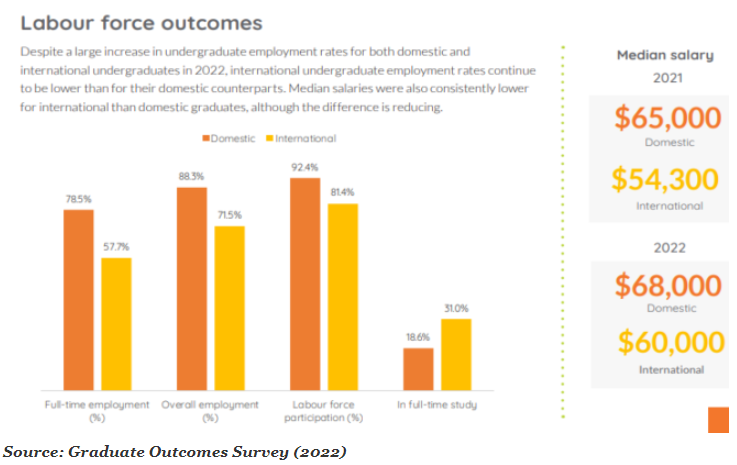

The most recent Graduate Outcomes Survey supports CEDA’s findings by showing that median wages, participation rates, and employment rates for international graduates are significantly lower than for domestic graduates.

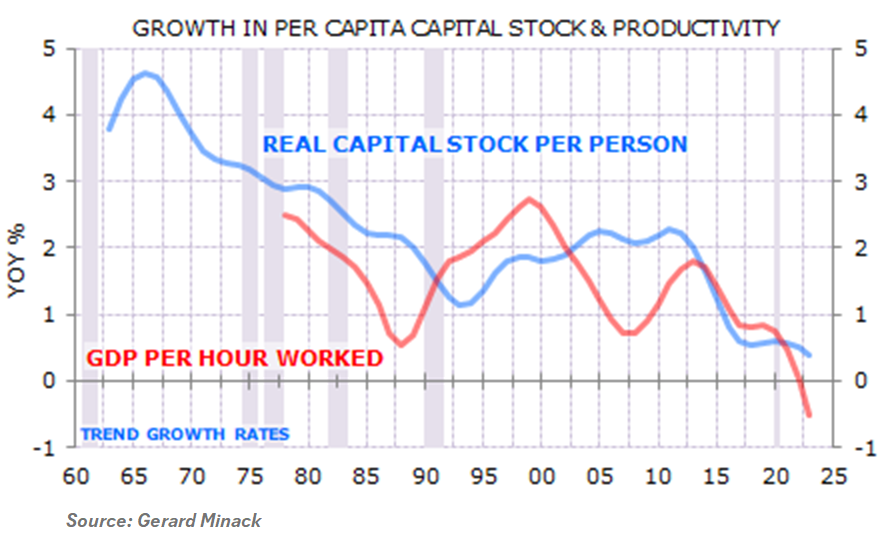

Independent economist Gerard Minack’s November 2023 research revealed that Australia’s 8.2 million population increase this century has outpaced the provision of business investment, infrastructure, and housing, resulting in what economists call “capital shallowing” and lower productivity growth.

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”, Minack wrote in his November report.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”, Minack wrote.

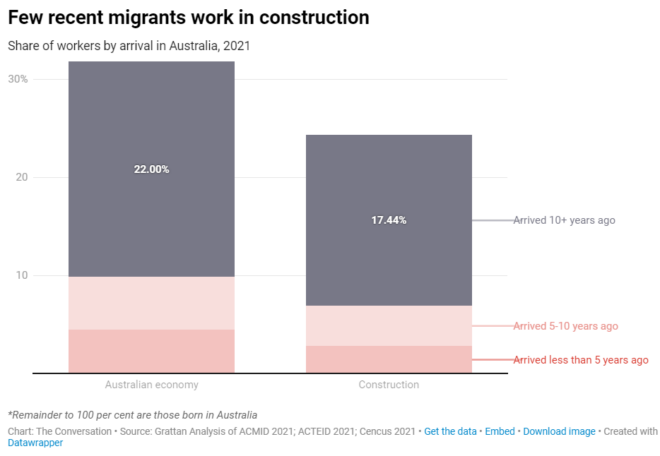

To add insult to injury, data provided by the Grattan Institute shows that a substantially lower share of migrants work in the construction sector than their Australian-born counterparts:

“About 32% of Australian workers were foreign born, but only about 24 per cent of workers in building and construction were born overseas”, the Grattan Institute wrote in January.

“And very few recent migrants work in construction. Migrants who arrived in Australia less than five years ago account for just 2.8% of the construction workforce, but account for 4.4% of all workers in Australia”.

As a result, Australia’s immigration system exacerbates the country’s housing and productivity challenges in two ways.

First, immigration levels are too high, overwhelming the economy’s supply side.

Second, the migration system is poorly targeted and does not deliver the skills the economy requires.

The fact that Australia’s population has increased by 8.2 million people (44%) this century alone, while skill shortages are worse than ever, is factual evidence of these realities.

Australia, therefore, requires a migration system that is significantly smaller in size and more focused on the skills we need.

Australia’s migration system must be calibrated to be below the country’s ability to provide housing, infrastructure, and business investment while protecting the natural environment (particularly water resources).

Otherwise, Australia’s housing shortage will become permanent, while productivity growth and living standards will continue to suffer.