The Albanese government has set a target to build 1.2 million homes over five years, beginning 1 July this year.

To meet this target, Australia must build 60,000 homes every quarter or 240,000 homes annually for five consecutive years.

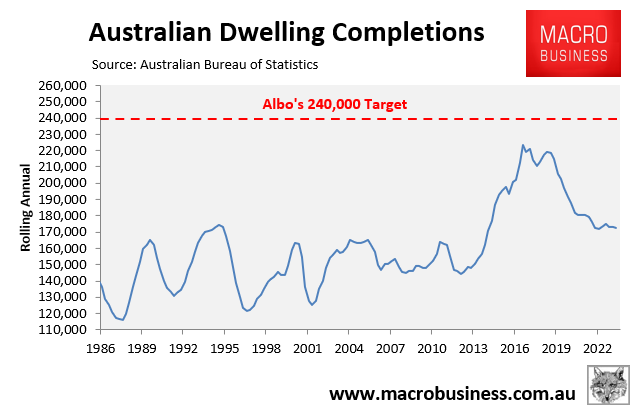

The following chart plots Labor’s housing target against Australia’s historical dwelling completions:

As you can see, Australia’s record annual dwelling completions were 223,000 in the year to March 2017, which was 17,000 below Labor’s target.

According to the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) figures, Australia completed only 173,000 dwellings in the year to December 2023, which was 67,000 below Labor’s target.

Worse, annual dwelling approvals (163,000) and dwelling commencements (164,000) are running even further behind the Albanese government’s 240,000 construction target.

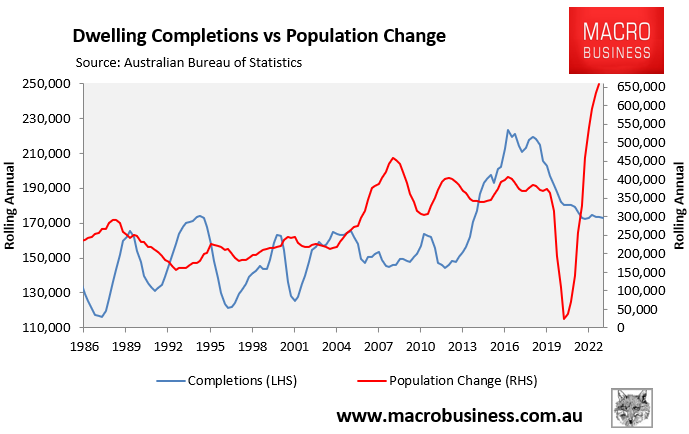

Meanwhile, Australia’s population is growing at a record pace, meaning there is a growing shortfall between housing supply and demand:

A new AFR survey of 12 property analysts and economists reveals that rising costs will make home building increasingly uneconomic, resulting in a decade long housing shortage and rental crisis.

“Of the myriad barriers to housing supply, the spike in construction costs is the most binding constraint and has dissuaded many developers from initiating a more robust supply response over the past year despite rapidly rising rents,” Knight Frank chief economist Ben Burston said.

Jarden’s chief economist Carlos Cacho said affordability was the “biggest hurdle” to increased housing supply, the result of a “perfect storm” of surging construction costs, high historic land acquisition costs and high rates, which have reduced borrowing power by 30-plus per cent.

“While there is clearly a strong level of underlying demand for new housing, particularly given record levels of migration, feasible prices for developers do not line up with what buyers are willing and able to pay,” he said.

“As such, it is unlikely we will see a material rise in new housing activity until interest rates fall. While efforts to cut red tape, increase densities around transportation hubs and generally make the development of new housing easier are a positive, we don’t expect them to make a material difference until affordability improves.”

Barrenjoey chief economist Jo Masters says “basic economics” is behind the collapse in dwelling construction.

The cost of building in most capital cities has been rising faster than home prices, making it less cost effective to build new houses than to buy an existing property.

“With labour and input costs elevated, and interest rates high, the numbers favour buying established over new houses”, Masters told the AFR.

“We expect a deep contraction in residential construction in the period ahead – the pipeline of work is being completed rapidly, completions are now above commencements, and building approvals annualised just 150,000 in February”.

Meanwhile, AMP chief economist Shane Oliver warned that with current immigration rates, Australia should be building 250,000 homes a year.

Oliver estimates that Australia’s shortage is running at 80,000 homes per year currently.

“Added on to the pre-existing shortfall, we expect the cumulative shortfall of homes to reach around 200,000 by June”, Oliver told The AFR.

CBRE research head Sameer Chopra said that supply won’t rebound until “prices have corrected higher and interest rates are falling (improving affordability)”, which “is unlikely to be significant until the end of the decade”.

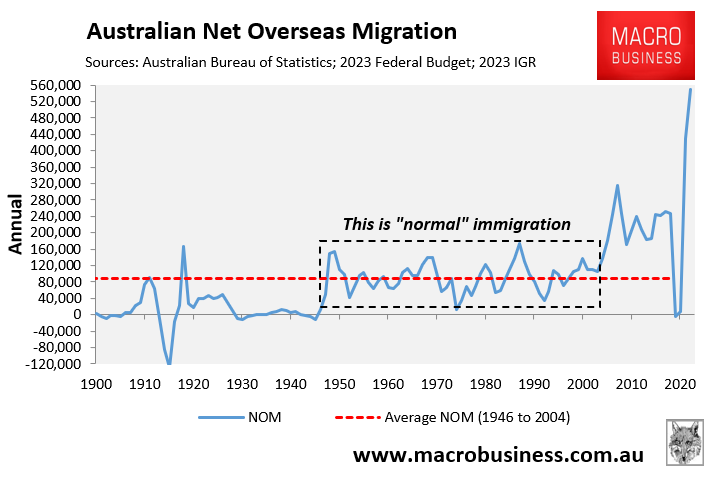

The bottom line is that Australia will never build enough homes to meet its rapidly growing population.

The solution, therefore, is to slash net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s ability to build homes and infrastructure.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing shortage will become permanent.