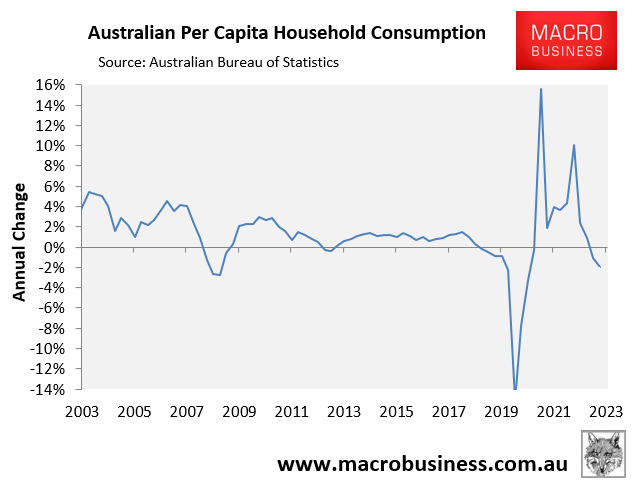

The December quarter national accounts release from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) revealed that real household consumption fell by 2.5% in per capita terms in 2023:

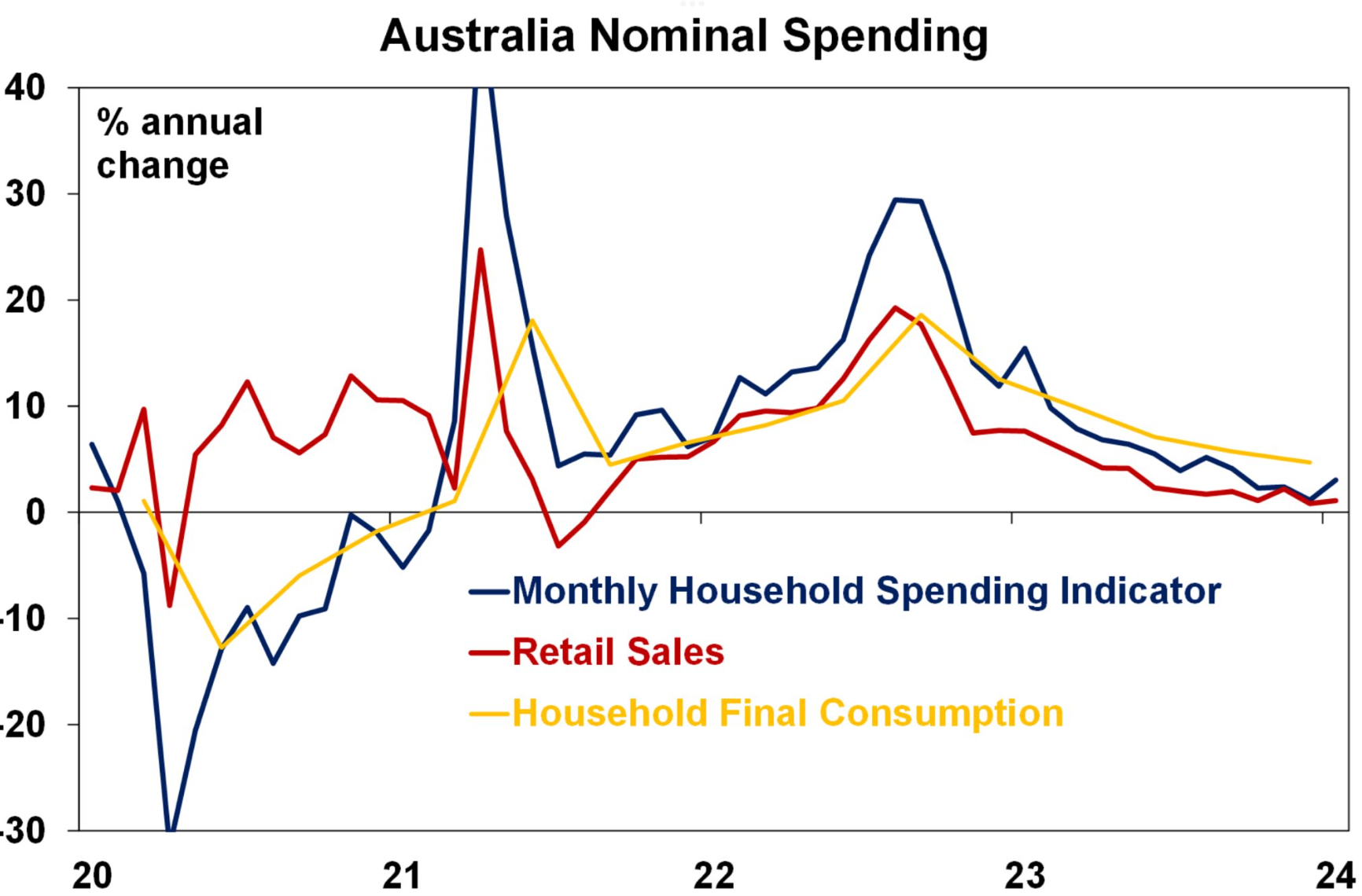

Last week, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released its household spending indicator for January, which revealed that household spending rose by 3.0% in nominal terms over the year.

The below chart from AMP chief economist Shane Oliver plots the series against the national accounts measure of household final consumption and the latest ABS retail sales data:

Source: Shane Oliver (AMP)

As you can see, consumption is universally weak, especially when you adjust for inflation and population growth.

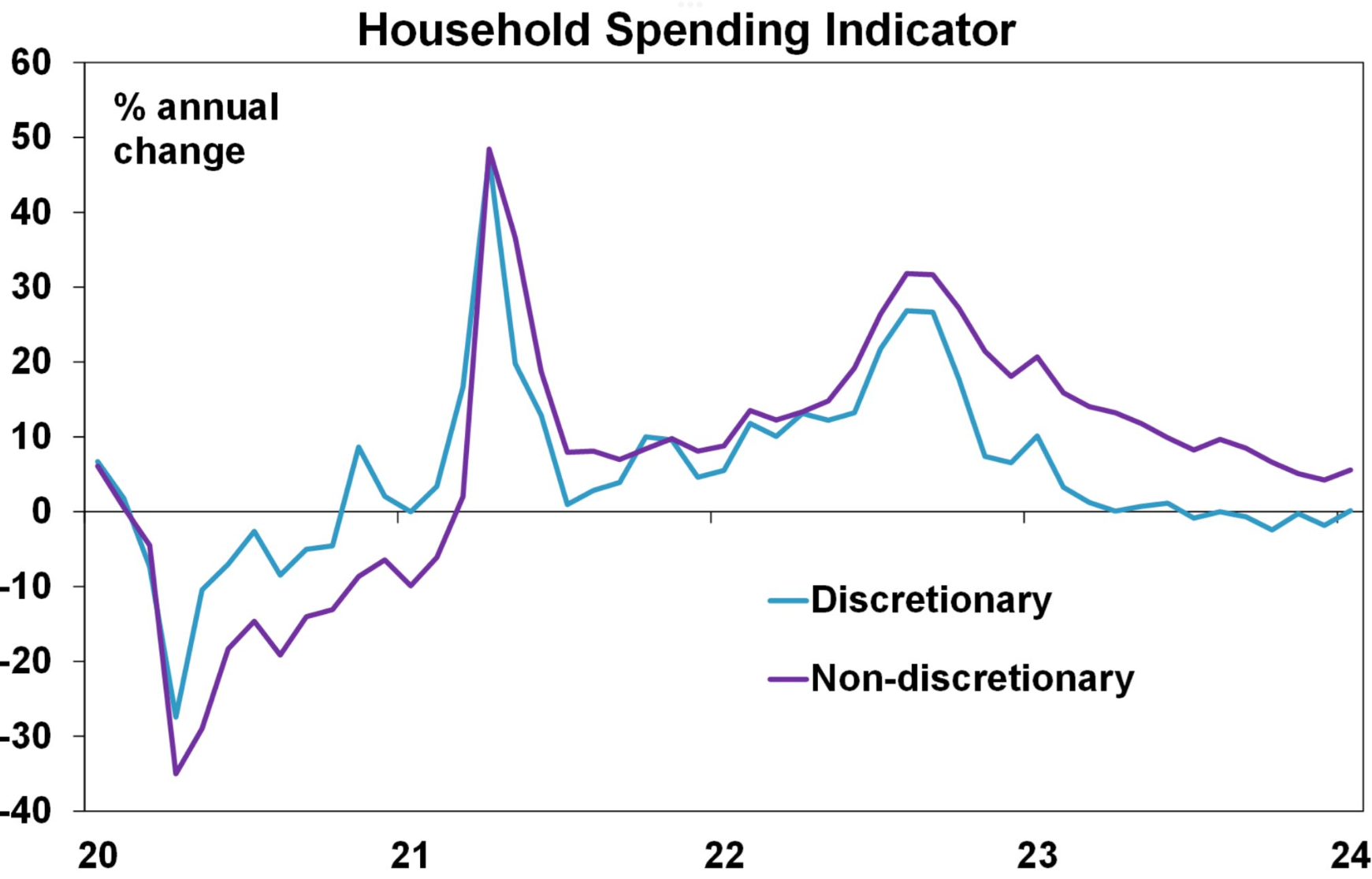

The next chart shows that households have cut back hard on discretionary spending, as expected during a cost-of-living crisis:

Source: Shane Oliver (AMP)

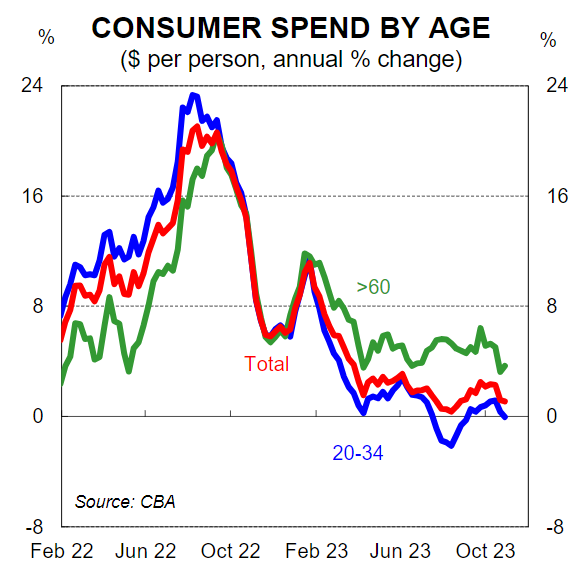

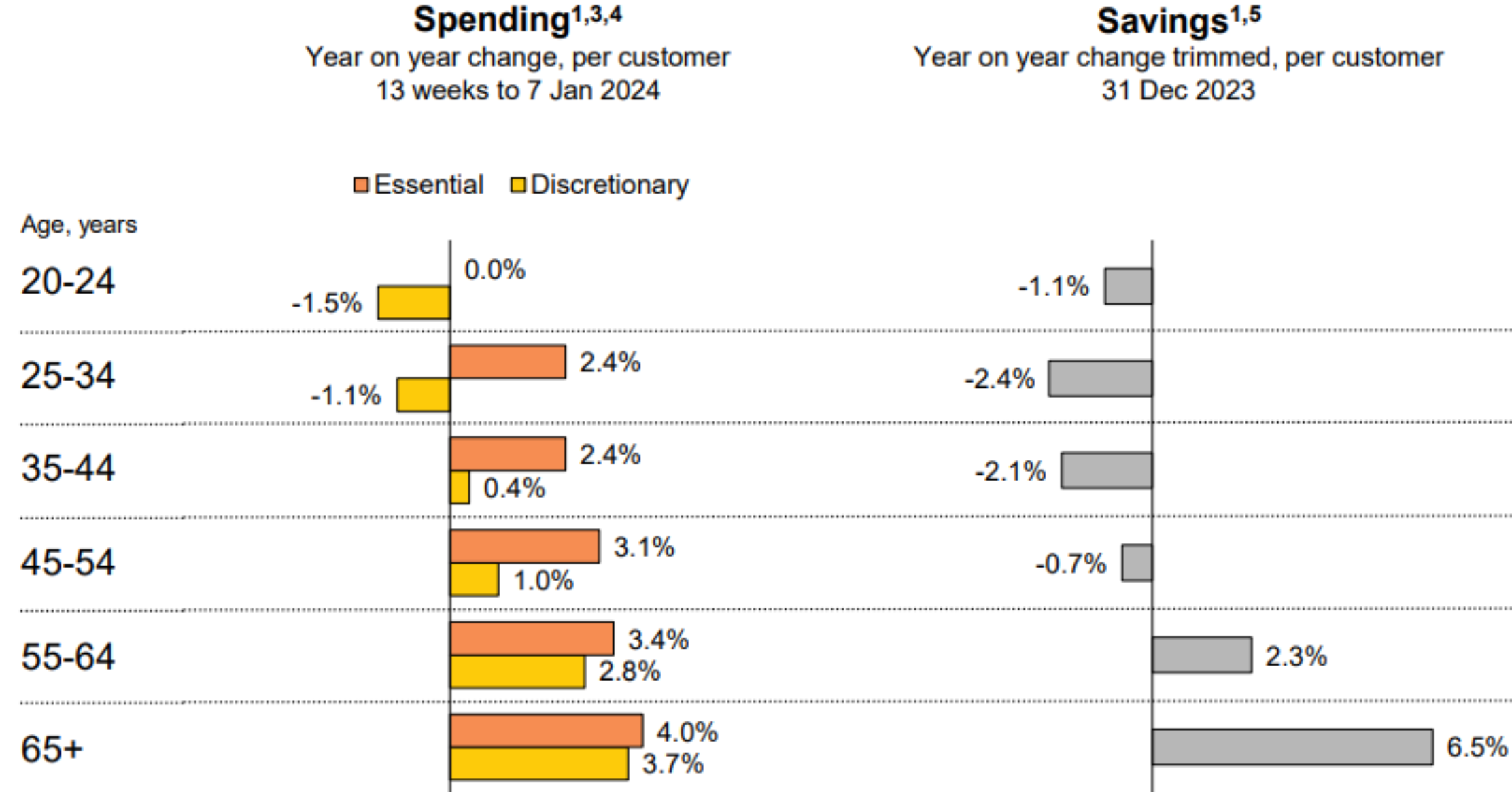

While Australians in aggregate have pulled back on consumption, the next chart from CBA shows the massive divergence by age cohort:

Source: CBA

As shown above, households aged 55-64 and 65-plus recorded far stronger spending growth in the year to 7 January than younger age cohorts.

The divergence is greatest with respect to discretionary spending, with younger households aged under 45 outright cutting spending, whereas households aged 55-64 lifted discretionary spending by 2.8% and households aged 65-plus lifted their discretionary spending by 3.7%.

The differences in savings between older and younger Australians are even more stark.

Households aged under 55 spent more than they earned (dis-saved) in 2023, whereas older Australians aged 55-64 grew their savings by 2.3% and households aged 65-plus increased their savings by 6.5%.

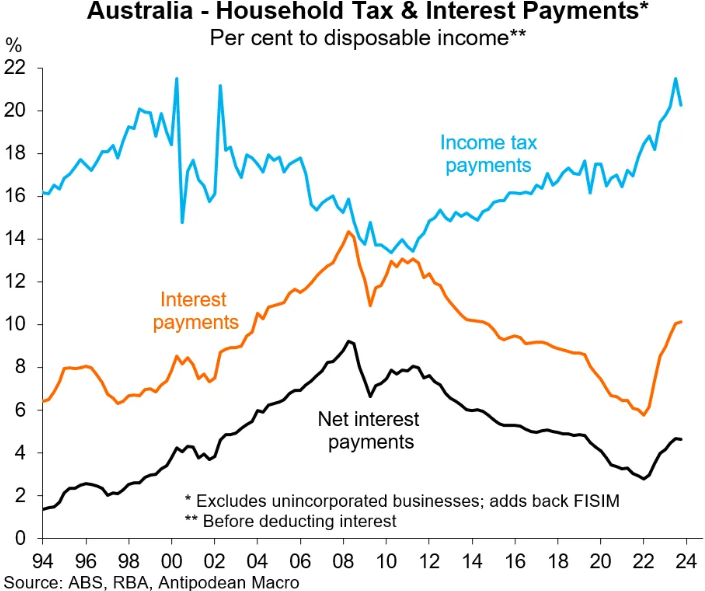

This is largely due to older Australians having lower (or no) mortgage debt, a higher proportion of households not needing to rent because they own their homes outright, earning higher interest on savings, and, in the case of baby boomers, not experiencing a financial hardship due to rising income tax payments.

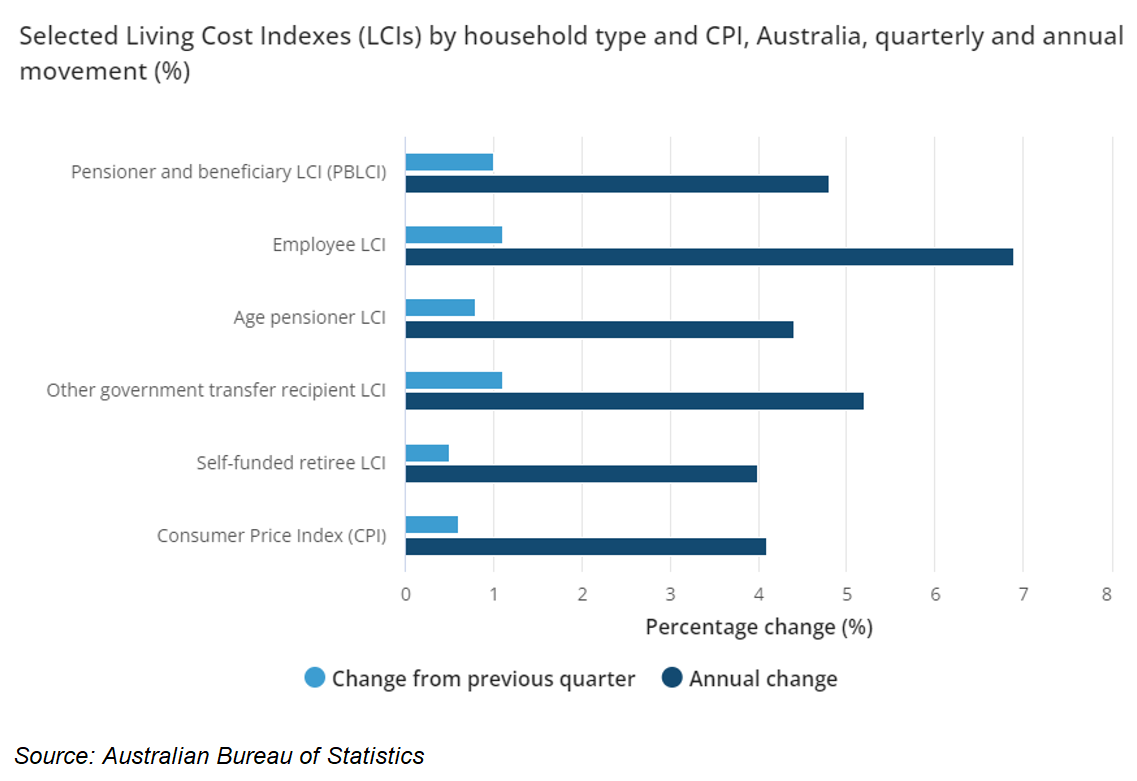

Reflecting these facts, the latest cost of living indices from the ABS showed that employee households had a 6.9% increase in their cost of living in 2023, far exceeding the CPI inflation rate of 4.1%:

Self-funded households, on the other hand, saw a slightly lower increase in living costs than CPI inflation.

The above data illustrates why Australia desperately needs tax reform that shifts the base away from productive activity (taxing work) towards more efficient sources such as resources, land, and consumption.

Australia’s current tax system is unsustainable, wasteful, and inequitable since it is so reliant on a diminishing pool of workers while the proportion of taxes collected via indirect sources (e.g., GST and fuel excise) declines.

This is especially true given that the older population is expanding and paying lower taxes than ever before, despite controlling the majority of the Australia’s wealth.